The Meitner Audio DS-EQ2 Optical Cartridge Phono Equalizer

i'm beginning to see the light

You’ll have to decide for yourself whether DS Audio President Tetsuaki “Aki” Aoyagi’s smarter move was instigating a 21st century version of the ‘70’s era optical phono cartridge or creating an open playing field upon which other companies could develop their own versions of the particular equalizer/preamplifier required to make the cartridge work.

Aoyagi, an accountant by training with a family background in high-tech laser optics could probably have fashioned a closed system business model in which DS Audio cartridges were available only with DS equalizers, but he smartly chose otherwise, realizing that few vinyl fans accustomed to “mixing and matching” cartridges and phono preamps would be attracted to a closed system.

The young man’s vinyl epiphany came a decade ago when he heard Thriller on vinyl, played back using a vintage Toshiba C-100P optical cartridge that employed a filament-based light source. The heat producing filament made the cartridge prone to fail, which is why the design faded. The record obviously sounded far better than the iPod version and well, you know the rest, which explains why this year 52 million new records are expected to sell.

A decade ago, Aoyagi and his team set out to use modern, cool running LED technology to produce a reliable optical cartridge system and today the company’s products—both the cartridges and phono equalizers— are fully established and well-respected in the vinyl enthusiast audiophile community. I visited the factory in 2017. You can find the video on my previous endeavor’s YouTube channel.

For those unfamiliar with the technology: optical cartridges use a standard cantilever/stylus assembly but employ as a light source LEDs (light emitting diodes) and photo-cells that detect brightness changes produced by a “shadow” material that partially blocks the light from hitting the photo cell. Stylus movements modulate the LED light hitting the voltage producing photo cell.

So simple in principle. No magnets, no coils, super low mass, but not so simple to effectively design and manufacture. If you want to learn more about how it works Go Here. While the principle has remained fixed, over the past decade DS has greatly updated and improved implementation to deal with mechanical and electrical issues that while different from those affecting magnet/coil systems, nonetheless occur. More about that coming up.

The required equalizer differs from a standard phono preamp as greatly as the optical cartridge differs from one using magnets and coils. One difference is that the equalizer must supply power back to the cartridge to light the LED. Another, and the more critical one, is that like the coil/magnet-based cutter head, coil/magnet-based phono cartridges are velocity sensitive devices that output voltage relative to displacement over time (rate of change). Optical cartridges output voltage directly proportional to cantilever amplitude (amount of change)—and compared to MM and MC cartridges the voltage output is far greater.

All the records in your collection were cut using a coil/magnet-based cutter head modulated by RIAA curve electronics that to put it in simple but not wholly accurate terms, attenuates bass frequencies and boosts treble frequencies, their correct amplitudes restored by an inverse curve during playback.

The cutter head, produces a velocity proportional to the input voltage, not a displacement proportional to the input voltage. A MM/MC cartridge likewise produces an output voltage proportional to the velocity, not the displacement, so its frequency response will be linear, or flat, only when it's fed a constant-velocity signal.

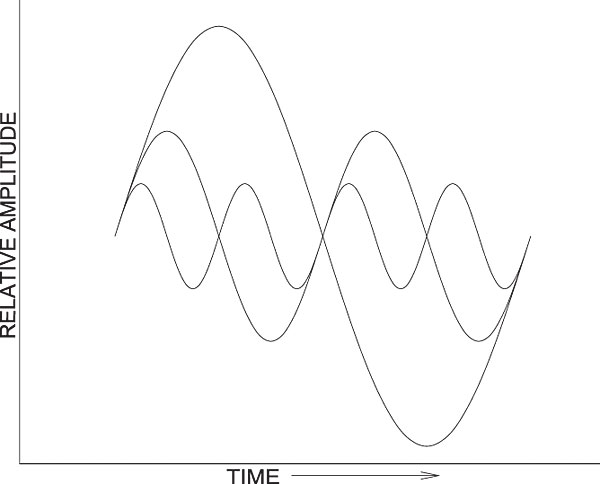

Though cutter heads are velocity-based, records can be cut both with constant velocity or constant amplitude. A constant velocity cut results in flat frequency response requiring no playback equalization, but that’s not practical because it would require enormous “real estate”-wasting low frequency groove excursions and tiny higher frequency ones. Why? Because a stylus tracing a high frequency signal moves a greater distance in a given period of time than it does tracing a low frequency signal if both are of the same amplitude. To keep the velocity constant at all frequencies over time, the amplitude must be halved as the relative frequency doubles.

Constant velocity cutting results in large groove excursions at low frequencies and ultrasmall excursions at higher frequencies (image by Gary A. Galo).

Constant velocity cutting results in large groove excursions at low frequencies and ultrasmall excursions at higher frequencies (image by Gary A. Galo).

Records can also be cut with constant amplitude where regardless of frequency the amplitude (level) remains constant. As the frequency lowers, the amplitude doesn’t increase so neither do the groove excursions, thus more music can fit on the side of a record.

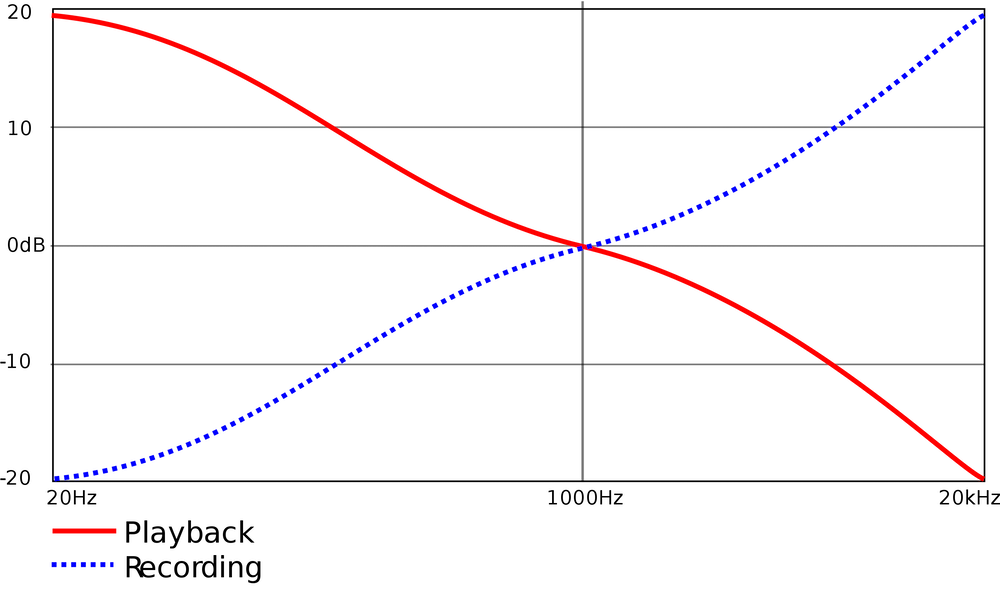

But the cutter head is a velocity-sensitive transducer, so maintaining constant amplitude requires a 6dB/octave rise in the signal fed to the cutter head, which would produce a far more linear line than the wavier upward line seen in the RIAA “preemphasis curve” graph.

Theoretically an RIAA phono preamp produces an inverse of that curve to output flat response, but the reality is far more complex because, for starters, constant amplitude into the lowest frequencies below 50Hz during cutting would mean a boost during playback that would amplify rumble and noise and produce spikey wave radii in the highest frequencies no playback stylus could accurately trace. That’s why records are cut and played back using both constant amplitude and constant velocity in different parts of the frequency spectrum.

Below 50.5 Hz cutting is constant velocity, which produces what’s known as the bass “shelf”— flat response without equalization when using MC/MM velocity sensitive cartridges. This takes up a bit more “real estate” but means avoiding a playback amplitude rise that would boost rumble and noise.

Between 50.5 and 500.5Hz (the "bass turnover" point), cutting is constant amplitude. Between 500.5 and 2122Hz (the "treble transition"), cutting reverts to constant velocity; above 2122Hz, it is again constant amplitude. The rise in the curve above 2122Hz, though called "treble pre-emphasis," does not really depict increasing amplitude, but an increase in recorded velocity. Boosting the amplitude would make tracing the groove in playback more difficult.

The velocity sensitive playback cartridge produces flat response for the constant-velocity portion of the curve, and for the constant-amplitude portion its output rises at 6dB/octave, which must be compensated for by the inverse RIAA curve built into phono preamplifiers.

If you’re following this (and if you are not, I fully understand!) you realize that an optical amplitude sensitive cartridge requires very different equalization at these various points than does a velocity sensitive cartridge.

I don’t want heads to explode so I’ll stop here. However, if you wish to really educate yourself about this subject, please watch this video:

When I spoke to Ed Meitner about all of this, he made it sound very simple: "A position sensitive cartridge like the DS Audio optical cartridge looks at the frequency range from 50Hz - 500Hz as constant amplitude without needing RIAA correction. From 500Hz - 2kHz it is constant velocity, meaning the amplitude gets smaller with increasing frequency, so we need a correction of 12db. From 2kHz-20kHz and beyond, we are back to constant amplitude and do not need RIAA correction.”

Equalization issues aside, you can easily understand why the optical cartridge’s ultra-low mass design can move through the grooves and respond to modulations with an ease no magnet/coil system manages, much as moving coil designs respond more quickly than do ones where the heavier magnet does the moving. Plus, there’s no generated “back EMF hysteresis” to slow things down.

Almost a decade ago I was one of the first to review the original DS-W1 “Nightrider”, an $8500 cartridge + equalizer combination and probably the only one to give it a negative review because the response was obviously anything but flat. The amount of bass boost (or the equalizer’s inability to deal with the “shelf”) was excessive to where it was distracting and there seemed to be a treble peak that made a moving coil’s high frequency resonance sound tame by comparison, though its character was somehow more forgiving. I didn’t measure any of this, but it was easy to hear as were other sonic issues.

Some reviewers loved the excess bass, which they characterized as “better” bass, and all or most of them were so mesmerized by the concept of a modulated light beam, all else was forgiven or ignored. It was reminiscent of the compact disc’s uncritical reception because, wow, it’s read by a laser. To be fair, from the get-go the DS-W1 delivered a few superior sonic qualities no coil/magnet cartridge manages—especially quiet backgrounds and a sense of unfettered speed.

I concluded my decade old review with:

“My biggest problem with the sound of the DS-W1 was that its bass output was excessive and obtrusive, not to mention less well-defined and less coherent than the ideal. I also felt that the cartridge's dedicated equalizer just wasn't good enough for an $8500 product that had to be purchased as a system—and so the electronics couldn't be upgraded. For that money, you could do better.”

Over the past decade DS Audio has made numerous major improvements to the mechanical design of its cartridges and as well to the equalizer electronics, and it now offers a complete line up of “mix’n’match” cartridges and equalizers covering a wide price range—including the top of the line $22,000 Grand Master EX cartridge that utilizes the same Orbray one piece diamond cantilever/stylus assembly Audio-Technica uses in its $9000 limited edition AT-MC2022 cartridge (Adamant Namiki Precision Jewel Co. Ltd. changed its name to Orbray January 1, 2023) and of course DS has wisely opened the system up, so equalizers designed by other manufacturers can be used.

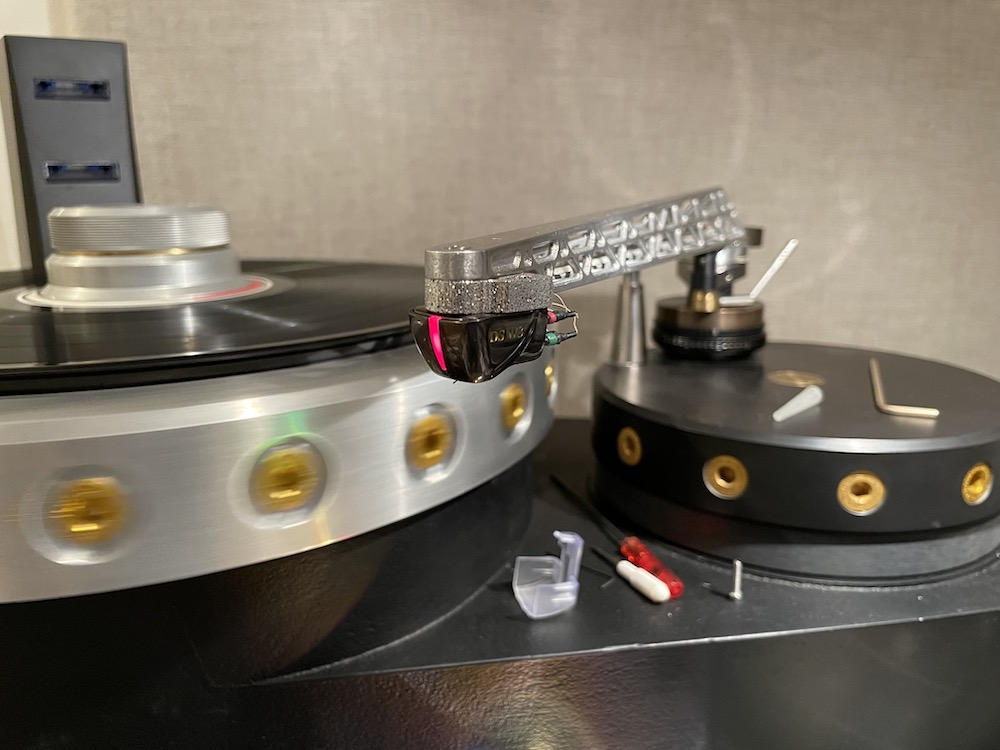

For this Meitner Audio DS-EQ2 review, I was supplied with a $5000 DS W3 optical cartridge, a fairly recent design that borrows a great deal of tech from the flagship and far more costly Grand Master. Among its features are independent LED and photo-detectors for each channel, which results in an output increase of from 40mv to 70mV. Despite the voltage boost DS claims the W3’s signal to noise ratio is higher, resulting in a lower noise floor and “…greater musical clarity”.

DS claims the new dual LED/photo-detector design “…has made it possible to eliminate crosstalk, greatly improving left and right channel separation (in particular the high-frequency separation has improved by 10dB in comparison to its DS Audio forebears).” The “eliminate crosstalk” is clearly a misstatement.

The new “dual mono” arrangement required a redesign of the “shading plate” that controls the light reaching the photo-detector. It’s now smaller, and substitutes 99.9% pure beryllium for aluminum, which was used on the previous generation. This change results in a greater than 50% reduction in shading plate weight, which, according to the literature, is now “less than 1/10th the mass of MC coil and core systems” (including the “core” mass instead of just comparing coil/former mass and shading plate masses produces a misleading and unnecessary spec comparison in my opinion). The result of all of this is a much-improved cartridge— sonically, mechanically and no doubt in terms of measured performance.

The aluminum bodied DS W3 features a familiar looking Ogura boron cantilever/line contact stylus assembly.

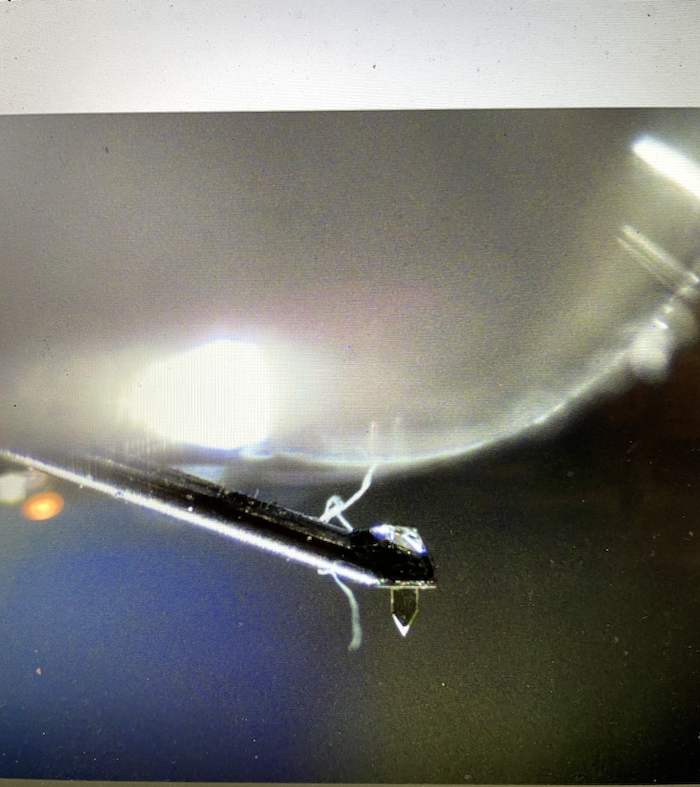

(hair removed before playback)

(hair removed before playback)

Channel separation is spec’d at 27dB+ (@1kHz), with 1.95g recommended tracking force. The W3 is housed in a rigid aluminum body and weighs 7.9 grams. The W3 costs $5000, which in today’s top tier market, especially given the construction quality and unique tech, makes it an attractive option. Especially when combined with….

The Meitner Audio DS-EQ2

Ed Meitner has long been more interested in DSD technology than in vinyl playback, though like everyone else from his generation (and mine and maybe yours), vinyl was the source for much of his music listening life.

The optical cartridge piqued his curiosity, so he bought a W2 and “dusted off” his record collection. The EMM Labs website relates his reaction:

“Compared to his reference MC cartridge, the W2 exhibited improved resolution, clarity and low frequency response”. That’s straightforward enough. Clearly, the experience prompted Mr. Meitner to become more deeply involved. “Upon receiving the full line of DS Audio cartridges, Ed immediately recognized a common sonic signature within the line, increasing in its degree of refinement and depth from the entry-level E1 to the flagship Master1 cartridge.” The experience prompted Meitner to design his own optical cartridge equalizer. The result of Ed’s work was the DS-EQ1 Optical Equalizer.

The DS-EQ1, according to the EMM Labs website “…. is designed with an obsessive desire to lower noise and distortion, and to extract every bit of detail and information from any DS Audio optical cartridge. The DS-EQ1’s circuits are all Meitner designed in-house, including its power supply, and are optimized for short and direct audio paths. EMM uses a custom-made ceramic PCB for the equalization and amplification stages, which allow for the superior extraction of low-level details in the audio.” The DS-EQ1 offers both balanced and single-ended outputs."

The EQ1 costs $12,500. The current top of the line DS Audio equalizer is a massive two chassis design costing $45,000. Wouldn’t a comparison be interesting? Okay, I’m off topic now.

Meitner decided a less costly DS equalizer would make sense, one that made use of all he learned designing the EQ1. The resulting EQ2 is a smaller, single-ended only equalizer housed in a less opulent, but nonetheless sturdy, well constructed chassis. Like the EQ1, the EQ2 features “proprietary and discrete equalization specifically designed for all DS Audio optical cartridges”, as well as custom designed single-ended discrete Class A amplification second order 15Hz low pass pass filter, and a few other features, but basically it’s a simplified version of the EQ1 EMM Labs is able to sell for $5000, bringing the total cost of the “system” under review—W3 cartridge plus phono equalizer—to $10,000.

Not exactly “chump change”, but that’s the cost of cartridge and phono preamp, which makes this a very competitive proposition. You could buy the equalizer and start with a less costly DS cartridge to hear if you even like the sound, because as Ed noted, there is a “common sonic signature” within the line that you will either like or not like. I take that comment to mean the optical cartridge system itself, not the equalizers. “A common sonic signature” is true of most audio products especially cartridge and loudspeaker lines, regardless of technology.

My reference front end includes cartridges like the Ortofon Diamond ($10,000), the Lyra Atlas SL Lambda ($11,995), the Haniwa HCTR-CO and the Audio Technica AT-MC2022 ($9000) run into the CH Precision P1/X1 phono preamp ($48,000). This is a review of a $5000 cartridge and a $5000 phono preamplifier.

Set Up and Sound

I installed the W3 on the Schröder OMA tonearm mounted on the Richard Krebs designed K3 turntable, setting tracking force at 2 grams. The cartridge’s relatively shallow height was not a problem here, though it might be on some arms. DS includes a series of spacers. Its wide body makes setting stylus rake angle a bit tricky but no more so than on other similarly situated cantilevers on wide-bodied cartridges. Otherwise setting up an optical cartridge is no different than setting up any other cartridge, though the W3 (and probably all of the dual LED/photo-detector equipped DS cartridges) was particularly sensitive to azimuth. Very slight adjustment produced larger than usual variations in L-R, R-L channel separation and balance, but once correctly set, which in this case was very slightly off from cantilever perpendicularity to the record, channel balance was better than .5dB between channels and separation was 29.5 and 30 dB. Also, SRA was 92.4 degrees with the arm parallel to the record surface. In other words, in every respect, this was a well-constructed cartridge.

Examining and determining SRA using WallyScope

Examining and determining SRA using WallyScope

The EQ2 features a pair of large front panel touch screen type buttons. One supplies power to the LEDs (through the negative cartridge pins) and illuminates the red stripe bisecting the cartridge body front. The other, should you choose to select it, applies a second order 15Hz low pass filter to deal with rising low end characteristic of all DS cartridges I've heard— and I’ve heard more than a few here and elsewhere including the three times the cost $15,000 Grand Master, the source of much of the W3’s technology. Rather than offering low pass filter choices as different rear panel outputs, Meitner makes it a convenient front panel push button option.

In fact, at High End Munich 2023 in the Marten room I listened to more than an hour’s worth of familiar recordings I’d shlepped from home, through the $22,500 DS Grand Master EX mounted on a Reed 5A arm/AirForce III turntable combo—power and EQ provided by the $45,000 Grand Master equalizer. The combo produced explosive dynamics, subterranean and rock-solid bass and genuine “wowza” excitement through the Marten Mingus Septet speakers, making their debut at the show.

The supplied cartridge had had some break-in so after a few track “warm up” I got right to it and played straight through the four LP box set Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis with Shirley Scott Cookin’ with Jaws and the Queen (CR00540) recently issued by Craft Records. These were all originally recorded in Rudy Van Gelder’s Hackensack living room studio between June and September, 1958 and here mastered by Bernie Grundman from the original sixty five year old analog tapes.

Davis played in sophisticated big bands with Basie, and in small groups like this blowing freely at the intersection of jazz and r&b. This is body and soul music, not head-scratching jazz. If you’re looking for a way into jazz—especially if rock and r&b are what you mostly listen to— take the leap here, get to Lester later!

Through any of the aforementioned cartridges into the CH Precision P1/X1 phono preamplifier these records put you in Rudy’s living room. On the first LP, Cookbook Vol. 1 “Lockjaw” on tenor is on the left channel—later flutist Jerome Richardson is there too, you can see organist Shirley Scott’s Leslie cabinet clearly placed in the middle of the room, staring you in the face, and over on the right is bassist George Duvivier and drummer Arthur Edgehill, laying back a bit, there to provide rhythmic fill rather than to call attention to themselves. The action is really the Davis/Scott duet.

Davis’s sax has a recognizable “reedy grit” and Richardson’s flute could not sound more different—velvety-smooth, yet airy. You can hear the air moving. It’s a remarkable recording by the then thirty four year old recording engineer.

I realize that far less costly gear can also get you “there”, but with far less “there” there. I can confidently say that because I’ve got such gear here for review and it’s really good, and really cost-effective but it does not perform the way these top tier ones manage.

This $10,000 combo is every bit the “value proposition” Meitner claims it to be. It too takes you into the living room as only an exceptionally quiet phono preamp and high-resolution cartridge can. Images on the stage were three-dimensional: solid, stable and appeared well away from the speaker boundaries. Davis’s sax was timbrally convincing even on the deepest notes where I was expecting more than a touch of excess bass. Duvivier’s bass was also nimble, appropriately reserved and not artificially “present” or heard as “better” or more intense bass. Davis’s sax had reedy grit and only a touch of the smooth sheen that for me is an optical cartridge turn off, but an attraction for optical cartridge enthusiasts.

All of my negative expectations quickly evaporated.

My previous experiences with optical cartridges here, at shows, and listening on friends’ systems (other than to the Grand Master) have always made clear to me the sonic characteristics people who like this sound like, which are the things about it I do not—and like the proverbial elephant in the room, once you hear them you cannot unhear them: excess bass described as “better” or “deeper” bass that to me (but not to them) sounds added and not on the record, smooth instrumental textures that sound like “smooth jazz”—too smooth and pleasant (which they think sound more real) when there should be grit and edge, which I think sounds more real and they think is an added artifice produced by magnet/coil issues or by “back EMF”.

Davis’s sax had more reedy “grit” than I was expecting to hear. Scott’s B-3/Leslie had more “juice and gurgle” than I was expecting, Edgehill’s cymbals had less “airbrake” and more true transient shimmer and sizzle than I was expecting. All the optical cartridge qualities that I have grown to not like, that many others (including most other reviewers) love were if not 100% gone, so far gone as to be unimportant—including the high frequency “glisten” that makes optical cartridge presentation sound to me like DSD, which frankly, I’m not a big fan of, and Ed Meitner is—along with Positive Feedback’s David Robinson, who among audio reviewers I think is the format’s strongest advocate. I prefer PCM because listening to DSD I hear that smooth “sheen” and I do not like it. I’m not alone here. The two “camps” will never agree.

Blind Listening

Following that first encounter with this rig, I felt super-motivated to do some online research. The difficulty this reviewer faces here, is the usual “two products at once” review problem. Is what I’m hearing a much-improved cartridge, or is the sound much improved by Meitner's equalizer or both?

My former U.K. boss (for whom I have respect along with many hard feelings) regularly publishes in Hi-Fi News measurements along with reviewers’ observational findings. If you search on its website for DS Audio cartridge measurements, you will see that the older cartridges (when paired with DS equalizers) had up to an 8dB rise in the lower frequencies. 8dB! This is not “better bass”! It’s grossly non-linear bass I heard and reported in my original review but somehow the mesmerized ignored or missed it. Those lab reports are published minus commentary, which I find interesting.

The mids aren’t exactly linear either. And the sheen-producing high frequency peak that I could not not hear (not that I claim at my age to be hearing 15kHz, but I surely hear its effects) is also in those measurements.

There’s a more recent review on that site of this W3 cartridge by my friend Ken Kessler, who is an optical cartridge enthusiast, and the measurements show what I hear here: there’s still a low bass rise, but it’s far less severe, depending upon which of the DS equalizer’s low pass filters one chooses. With the 30Hz filter the rise is only 2dB. The 50Hz filter produces a 4dB rise, still about half of what the older generation of DS cartridges produced. I left the 15Hz filter engaged throughout the review process. I'm curious to know why Meitner chose 15Hz.

The high frequency peak has also been lowered in amplitude and moved up in frequency. So clearly, this new DS W3 is a much-improved cartridge that uses tech developed for the top of the line $15,000 Grand Master cartridge at 1/3 its cost.

I could go on with a long list of records I auditioned but what’s the point? I’ve already made this point: this new W3 cartridge incorporating technology from the top of the line Grand Master at 1/3 the price brings far more linear performance to optical cartridges as heard here through the Meitner Audio DS-EQ2 and as shown in measurements. Of course this results in far greater timbral accuracy and less coloration.

I don't do measurements but the sound produced by the Meitner Audio/DS W3 combination produced low noise and observationally low distortion. All of the benefits of low mass optical operation remain: black backgrounds, veil lifting transparency, far less additive bass, slammin’ macro and subtle microdynamics and almost total elimination of the “smooth plastic-y sheen” quality that has turned my ears off to the technology, replaced by far more satisfying "grippy" transient detail.

Conclusion

A few years ago I reviewed the DS E1 a $2750 optical cartridge/equalizer combination. It features an elliptical stylus mounted to an aluminum cantilever. What can you get for $2750—cartridge and phono preamp—that can complete with that package’s sonic performance? You could put together a few nice packages, but I’d not do so before hearing what the DS E1 does.

Now, with this $10,000 combination of the DS Audio W3 and the Meitner Audio DS-EQ2, I’ll say the same thing at this price point. There are many very good moving coil cartridge and MC phono preamp choices adding up to $10,000 but as I previously wrote about the DS E1, I wouldn’t put down the credit card before finding a way to listen to this combination.

Specifications

Stereo single ended (RCA) inputs and outputs

Output voltage: 0.5V nominal (~ -3.8dBu)

Output impedance: 150 ohms unbalanced

Dimensions (W x D x H): 338 x 286 x 67mm / 13.3 x 11.3 x 2.7in

Weight: 3.7kg / 8.2lbs

Finish: Fine bead blasted front panel available in silver or black

Designed and Manufactured in Canada

.png)