A near Garbarek experience

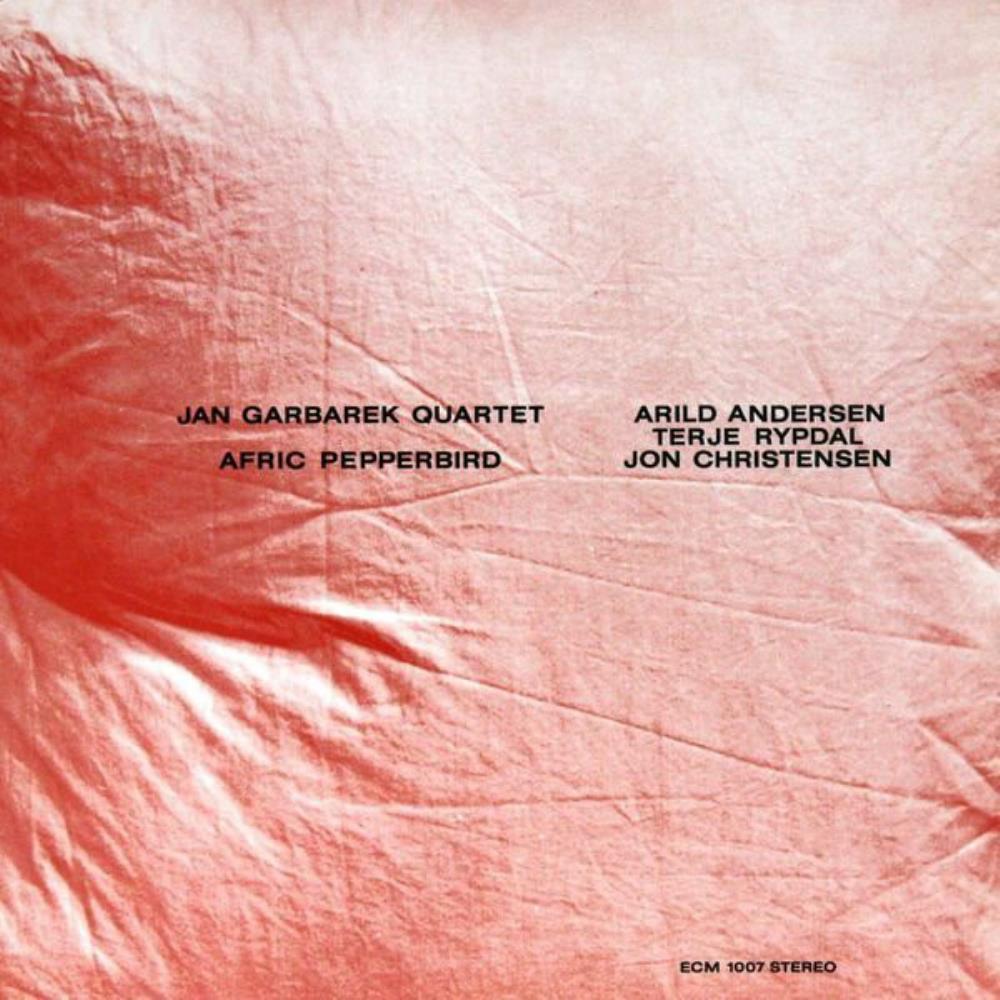

Excerpt from Jan Omdahl's new book on «Afric Pepperbird», ECM jazz touchstone by the Jan Garbarek Quartet

Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek is one of the most highly profiled artists recording for the German label ECM. He has released around 30 albums for the label as leader, and participated on many more. His collaborations with pianist Keith Jarrett, starting with the 1974 album Belonging, are among the label’s most celebrated. Afric Pepperbird (1970) was his first recording for ECM. The following is an excerpt from a book chronicling the making of the album.

In the anthology Contemporary Collecting: Objects, Practices, and the Fate of Things (Scarecrow Press, 2013), the author Evan Eisenberg argues that the collector is driven by the need to make beauty and joy permanent, and the need to comprehend beauty. By collecting, you ensure immediate access to physical manifestations of beauty and joy, always available to be experienced anew. Eisenberg also lists other, perhaps somewhat less admirable reasons to collect, such as the need to distinguish oneself as a consumer, the need to belong, and the need to impress others.

For some of us, the record collection is a physical manifestation of our place in the world. Collecting is a noble, but also somewhat lonely and borderline pathetic undertaking; a bit like running a museum not open to the public. From time to time I grapple with the sad realization that, sometime after my death, the buyer from the second hand record store will be the only person, other than myself, to gain insight into my collection's deepest qualities.

Afric Pepperbird (ECM 1007) was the label's seventh release, out December 1970.

Afric Pepperbird (ECM 1007) was the label's seventh release, out December 1970.

Still, I need more. Which is why I found myself, a few years ago, in a large, classic city apartment on the west side of Norway’s capital, Oslo. The apartment belongs to Anja Garbarek and her husband, John Mallison. Anja is the daughter of jazz saxophonist and ECM recording artist Jan Garbarek, herself a very gifted artist, with several critically acclaimed albums to her name. Balloon Mood (RCA, 1996) is an old favorite in my CD collection. Through mutual acquaintances, I had caught wind of the fact that Garbarek senior was selling parts of his vinyl collection. I was invited in for an early peek, the day before the son-in-law was to take Garbarek's records to a record fair at Rockefeller Music Hall in downtown Oslo. Surely a jazz record collector's dream scenario.

Foremost, there were loads of records Garbarek must have received from his German record company's distributor in Norway, or directly from the head office in Munich: piles of ECM releases in almost mint condition, from the early 1970s up to the time founder/producer Manfred Eicher started prioritizing the CD format in the latter half of the 1980s. Many of the records were mint, they might as well have come straight from the factory. I found a handful, but by no means all, of Garbarek's own releases. Alas, no Til Vigdis, his first and very rare recording from 1967, one of the most sought after and highest priced Norwegian releases. Only 300 were pressed, and near mint copies have retailed north of 2000 dollars. (My own copy fortunately didn't.)

The collection at hand did not give off much of a sense of the owner's life in music. What, for example, had become of the records Garbarek must have owned by early role models like Lester Young, Dexter Gordon, Don Byas and Archie Shepp, artists the legendary drummer and Garbarek collaborator Jon Christensen (1943-2020) had mentioned to me as important sources of inspiration for the young Garbarek? Where were the records he must have owned from formative years in the 1960s, by the likes of John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders and Miles Davis? Perhaps they had been sold at an earlier time, perhaps they were still in the apartment of Jan and his wife Vigdis, not too far away. I was hoping for the latter.

It seemed clear that Garbarek hadn’t wasted much of his days listening to what others were doing. But he had visited a record store every now and then; some of the records still had price tags from what was in its time the neighborhood's finest record store, Opus 8, on the corner of Bygdøy Allé and Niels Juels gate.

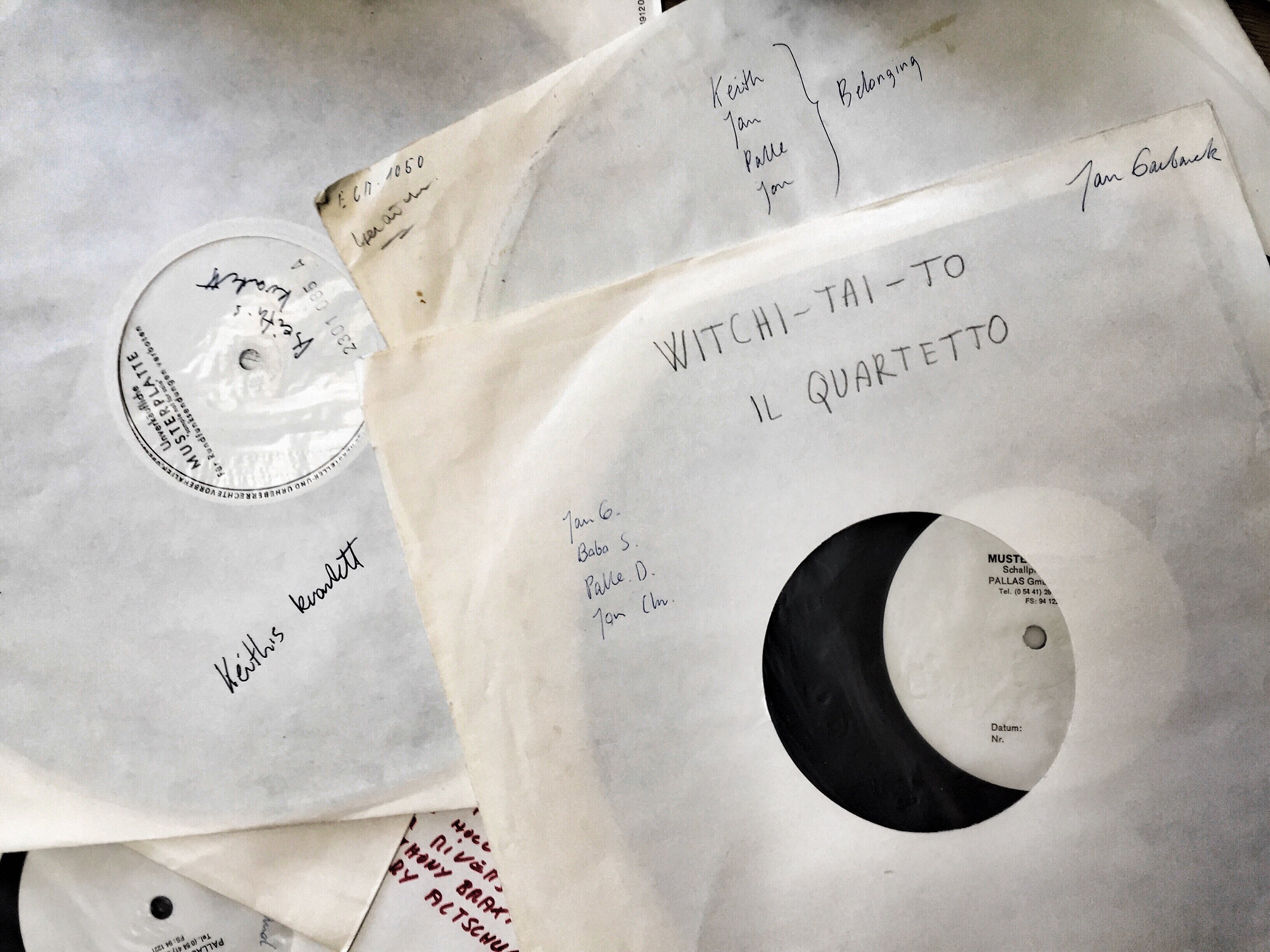

A selection of the test pressings the author ended up buying from Jan Garbarek's personal record collection. Photo: Jan Omdahl

A selection of the test pressings the author ended up buying from Jan Garbarek's personal record collection. Photo: Jan Omdahl

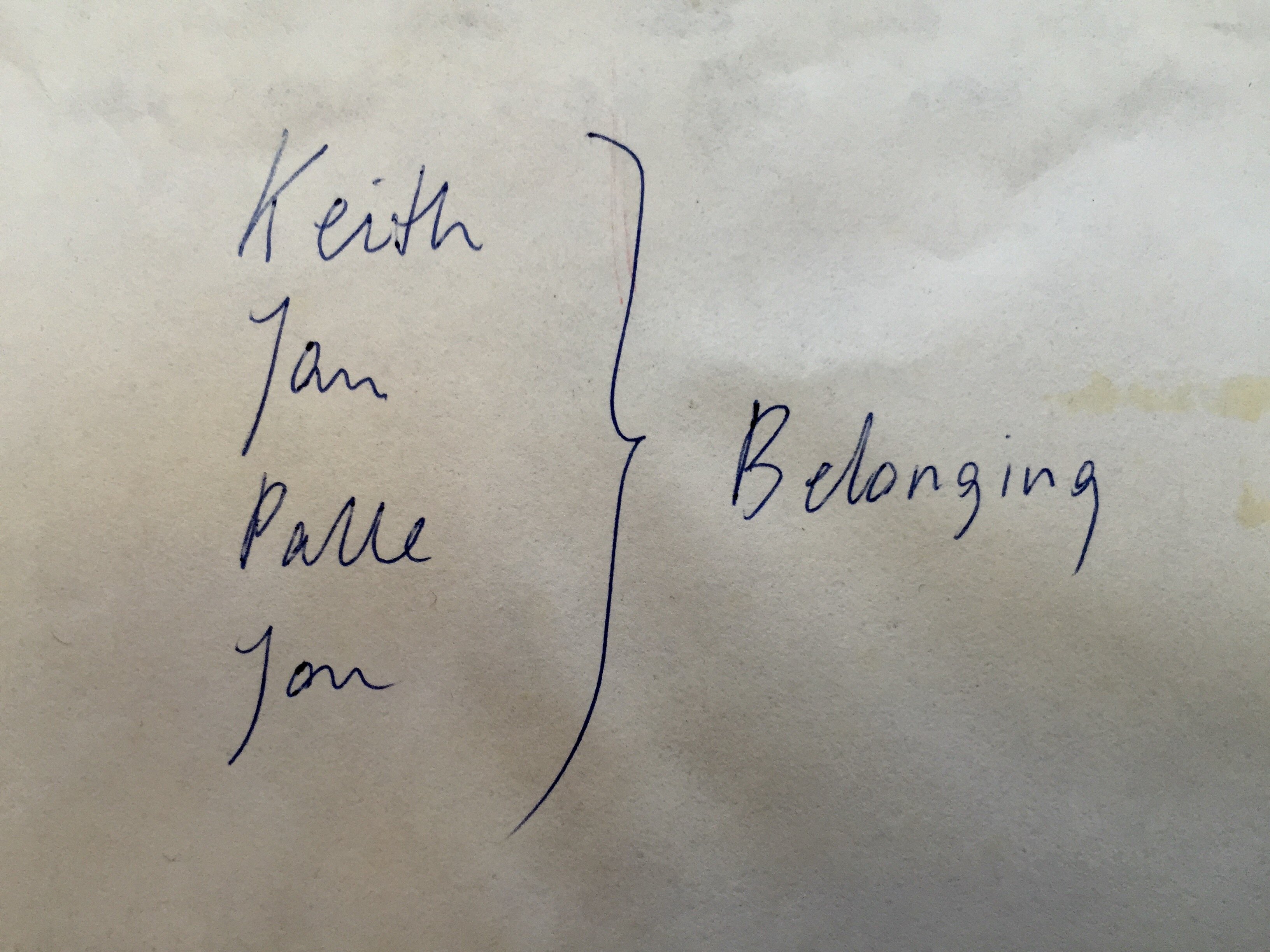

The opportunity to buy stacks of records from Garbarek's personal ECM collection was a rare treat. But then I made the real find: a substantial section of test pressings in anonymous white inner sleeves, a number of them with what had to Garbarek's handwritten notes on them. Test pressings are sent to labels and artists from the factory before the production run of a new album, so quality tends to be not too shabby. More important, from a collector’s standpoint, is the rarity, and how test pressings ooze a certain kind of insider music history vibe. They're process, not just product. When I found one where Garbarek had written "Keith's quartet" and "Keith, Jan, Palle, Jon" in brackets, with an arrow pointing to the word "Belonging", I felt tingly all over. Belonging, of course, is another early ECM touchstone, the beautiful first recording of Keith Jarrett’s European quartet, with Garbarek, Palle Danielsson, and Jon Christensen. Here in Norway, the record was something akin to a pop hit in the mid 70s, the kind of thing you might hear late at night at the right kind of party. When I showed the test pressing to musician and producer Erlend Mokkelbost, he suggested I must have Garbarek’s writing copied and tattooed on my shoulder. Maybe I should!

A friend suggested the author should have this tattooed on his shoulder. Photo: Jan Omdahl

A friend suggested the author should have this tattooed on his shoulder. Photo: Jan Omdahl

In the pile, a test pressing of the Norwegian composer Arne Nordheim's rare gem Popofoni was one of the few not from ECM. Among Garbarek's own recordings were, among others, Aftenland, Paths, Prints, All Those Born With Wings, Dansere, and Witchi-Tai-To. On the last one, Garbarek had written "IL QUARTETTO" in gray pencil, and "Jan G. Bobo S. Palle D, Jon Chr." with a blue ball point pen.

I bought all the test pressings, and far too many of the regular records. A small section of recordings of bird song undoubtedly said something significant about Garbarek's approach to his wind instruments, but I left them for someone with stronger jazz-ornithological leanings. The rest of the collection was transported to the record fair at Rockefeller the following day. My collector's fever was still raging, so I stopped by there also, buying a few more records from the Garbarek collection.

What I didn't know at the time was that this might be the closest I would get to Jan Garbarek in the process of writing this book, on the seminal 1970 ECM recording «Afric Pepperbird», made with guitarist Terje Rypdal, bassist Arild Andersen and drummer Jon Christensen, the first of many collaborations between producer Manfred Eicher and engineer Jan Erik Kongshaug in Oslo.

A very young Jan Erik Kongshaug behind the Neve desk at Arne Bendiksen studio in Oslo, Norway. He went on to record and mix several hundred ECM recordings alongside Manfred Eicher. Photo: Private

A very young Jan Erik Kongshaug behind the Neve desk at Arne Bendiksen studio in Oslo, Norway. He went on to record and mix several hundred ECM recordings alongside Manfred Eicher. Photo: Private

With the exception of a conversation with journalist Terje Mosnes for the journal Jazznytt (Jazz News) in 2015, it has been a very long time since Norway's arguably most famous and influential jazz musician gave interviews. When the musicologist and author Michael Tucker wanted to talk to him while working on a book about Garbarek's life and work, Deep Song (Hull Academic Press, 1999), the answer was also no.

I myself had first dipped my toe in with an email request, met with a short but polite refusal. On a later occasion, I took more direct action. Garbarek suddenly appeared in my peripheral vision at a tram stop close to a department store in central Oslo. The slicked-back hair, half-long, with a predominance of gray in the black; the slightly upturned dark eyebrows that give him that somewhat stern and questioning look; the sharp, handsome features; unmistakably Garbarek. He was dressed in a navy blue Canada Goose down jacket, blue jeans, black winter boots. No hat, even on a chilly winter day. He reminded me of a raven, standing against the wall at the back of the platform, probably waiting for line 12, which would take him to his home in the Frogner neighbourhood.

Garbarek was as anonymous as only a Norwegian jazz musician can be. Not a soul on the platform seemed to have an inkling that one of Norway’s biggest and most internationally renowned artists was in their midst. I hesitated, passed by at first, thinking this was certainly not the way to approach the notoriously private and media-shy saxophonist. But then, on the other hand: he was stuck there on the platform, with nowhere to run. An email or telephone call is easy to neglect, perhaps it would be more difficult to reject a polite request face to face? I had to give it a go. I turned, walked back, greeted him and introduced myself. His enthusiasm at my ambush was not exactly palpable, though he was friendly enough. After I had explained my errand, the temperature rose perhaps a few degrees. Garbarek smiled measuredly, listening politely. Could the man who, perhaps more than any other artist apart from Keith Jarrett, is associated with the ECM name, who must be considered Norway's greatest jazz musician of all time, and who was behind the album that started the collaboration between producer Manfred Eicher and engineer Jan Erik Kongshaug (1944-2019), thus contributing to connecting generations of Norwegian artists to the label for the next 50 years, consider saying yes to a little conversation?

Well, no, he couldn’t.

- I'm afraid I’m not interested. I think I'll have to say no. I was done talking a long time ago. I have learned from my wife that I need to make myself clear when I say no. "Did you say no just now? No one understood that," she usually says. So now I’m really saying no.

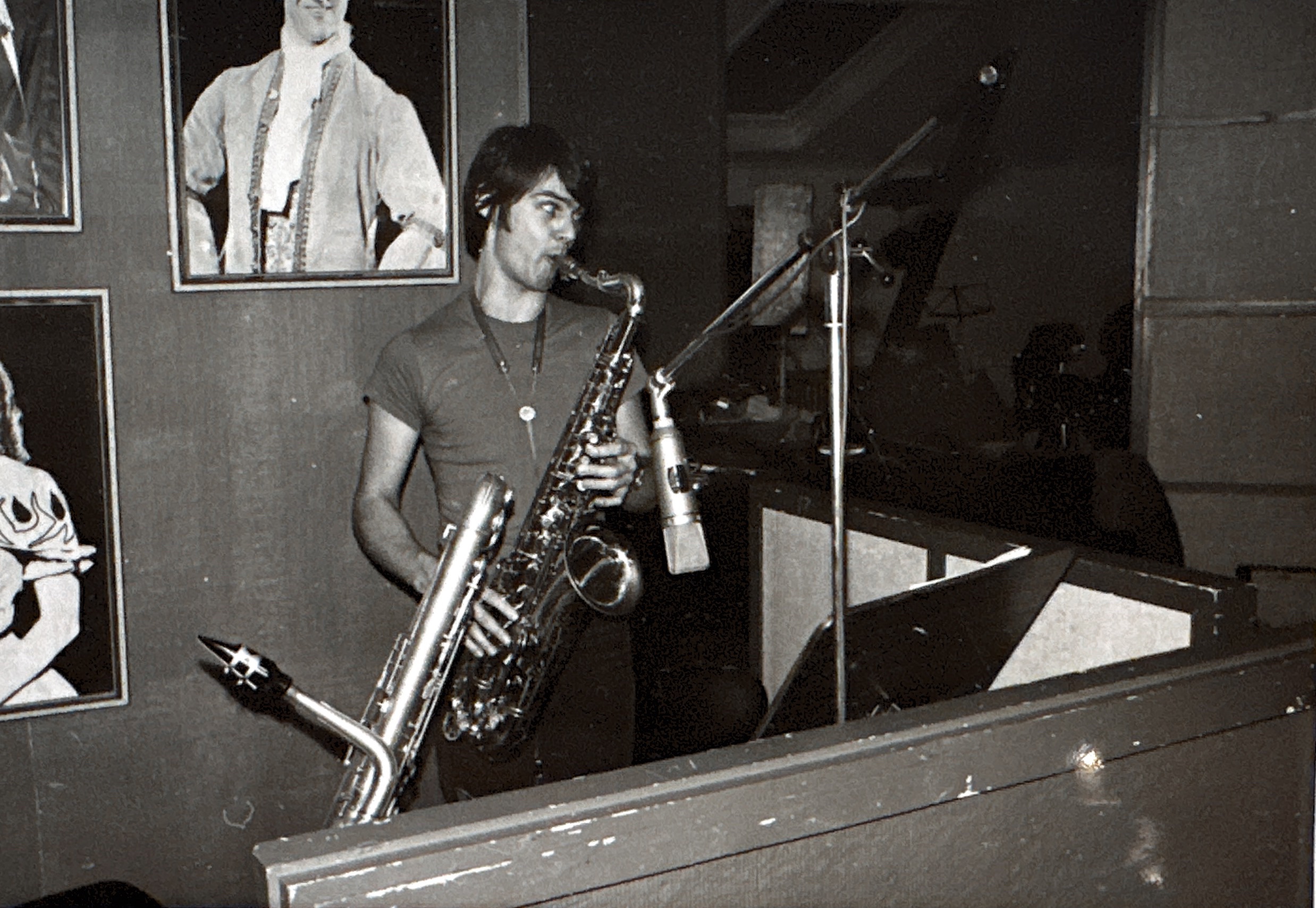

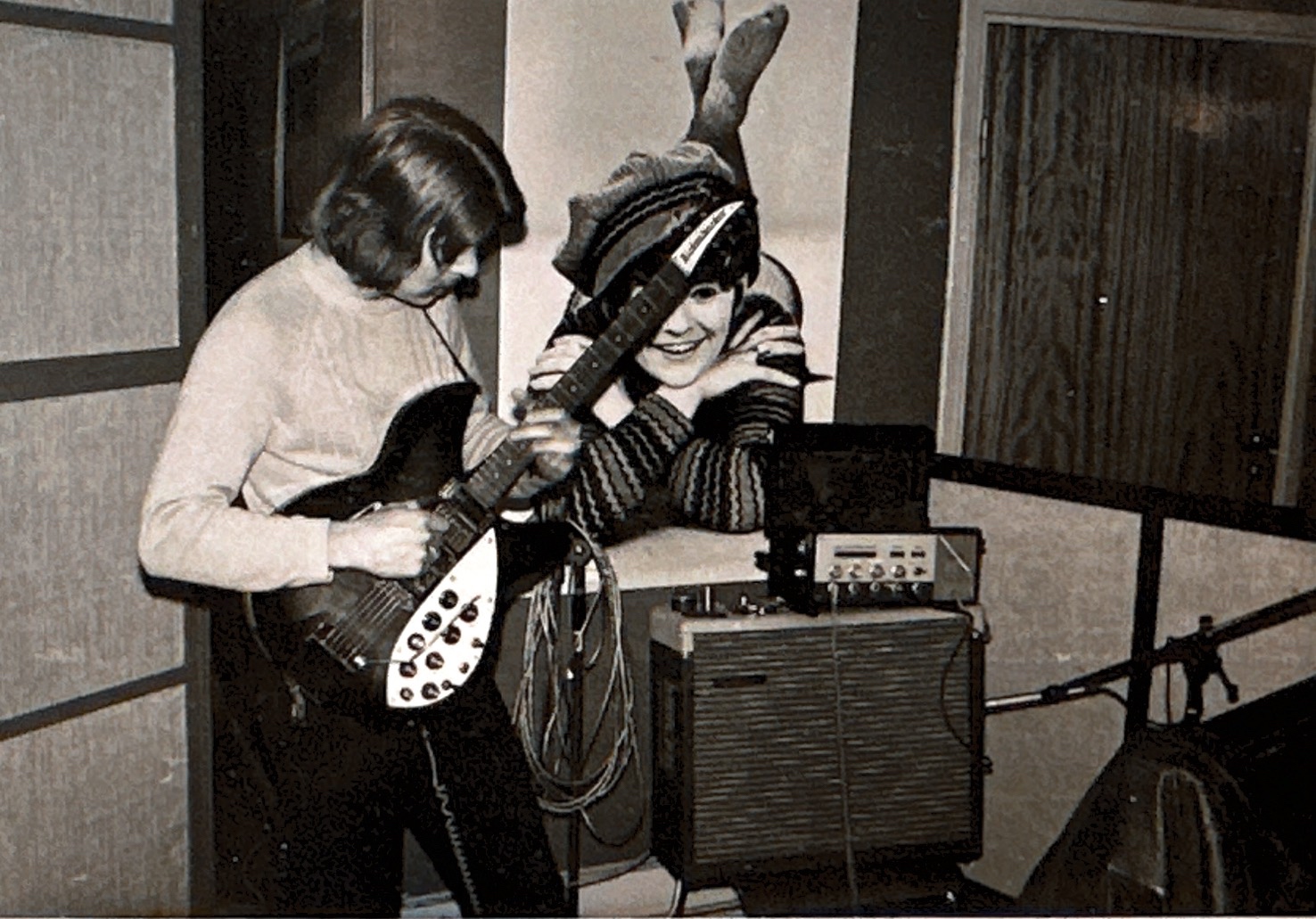

Jan Garbarek searching for his tone at the Bendiksen studio in Oslo, Norway, September 20th, 1970. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

Jan Garbarek searching for his tone at the Bendiksen studio in Oslo, Norway, September 20th, 1970. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

I didn’t give in right away, arguing that this was important cultural history, that Jon Christensen and bassist Arild Andersen had spoken willingly, that I had spoken a lot with Kongshaug, that Eicher was considering talking, that I had not yet given up on getting the reclusive Terje Rypdal to speak. The "big four" in Norwegian jazz, talking about this seminal moment of their shared past - it would have been beautiful.

- You mean the "old four", Garbarek replied. I mumbled something about the amazing work the four of them have done together, that it needed celebrating. But the legend couldn’t be budged. He said he hoped I would have better luck with Rypdal, was sure Eicher would like to talk about "the art of listening". He's just so busy, that man. Garbarek wished me luck, but as we parted with a handshake I couldn't help feel a tinge of annoyance. Wouldn't it have cost very little to contribute a few words about what happened, or just about Jan Erik, Jon, Arild, Manfred and the others? Then again, I obviously know nothing about what costs Jan Garbarek a lot and a little.

Garbarek's reluctance to talk should probably not be read as him distancing himself from Afric Pepperbird. But his first album for ECM clearly isn’t representative of the tone and style for which he would eventually become famous. Although it is a pillar in the discography, there are reasons to assume the great saxophonist much prefers other, later works in the catalogue. You won't have to go further than to 1974 and Witchi-Tai-To to find a greater artistic career highlight, but Afric Pepperbird has greater historical significance. That Garbarek feels more strongly connected to his later music, and to the highly personal and original tone he developed a few years further into the 1970s and beyond, than to this music from this earlier, wilder and more American-influenced period, is understandable. Precisely for this reason it is a shame he does not want to share some thoughts on the topic. Perhaps he has little desire to be confronted with even more of a certain type of criticism, the one which chastises him for his gradual move from the more radical free jazz-infused and Coleman/Coltrane-inspired ideas of his early career, in the direction of a more melodic, folk-music-influenced and romantic expression with strong connections to nordic nature. Or "state jazz", to borrow a slightly ironic phrase from Jazznytt writer Filip Roshauw.

Jon Christensen and Arild Andersen, during the recording of Afric Perpperbird. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

Jon Christensen and Arild Andersen, during the recording of Afric Perpperbird. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

The style he eventually came up with, just a few years after Afric Pepperbird, was all his own. It had fewer notes and more space, was open, slowly flowing and lyrical, almost architectural, striving for calm and balance. One could make connections all the way back to a Johnny Hodges of the 1930s, as well as to Miles Davis and Bill Evans in their lyrical and modal phases of the early 1960s. The tone was beautiful, but also unsentimental. It could be hard as granite, without a trace of soft vibrato. It was rich in overtones, nasal, but clear, sometimes sharp, almost shrill, with what Tor Dybo, professor of musicology at the University of Agder and author of the book Jan Garbarek: Det åpne roms estetikk (Pax, 1996), points out are end phrases that often fall suddenly, as in the lure of the Norwegian shepherd calling for the cattle; "kyRA".

It is impossible not to think there is something Nordic about this. The clean, ethereal, almost barren expression; it is the northern lights, the high mountain plains, the white snow, the cold arctic air. To quote his Norwegian Wikipedia article (my translation): "He is considered by many to be the most prominent representative of what is called “a Nordic tone", and is one of the originators of what is called "mountain jazz"".

Terje Rypdal, fusing rock and jazz on his Rickebacker. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

Terje Rypdal, fusing rock and jazz on his Rickebacker. Photo: Unknown, from Arild Andersen's scrapbook

Surely this must be hugely frustrating for an artist who has interpreted early music with the Hilliard ensemble, who has played music by composers such as Armenian Tigran Manusiran, Greek Eleni Karaindrou and Georgian Giya Kancheli, who regularly plays with the Indian percussionist Trilok Gurtu, and who has worked with Indian, Tunisian, Brazilian, Greek and Ivorian-French musicians. If you ask the Greeks, he sounds Greek, if you ask the Poles he sounds Polish.

But the connection to Norwegian folk music and natural romanticism is undeniably very strong and obvious in Garbarek's work. A composition such as "Molde Canticle" from I Took Up The Runes (1990) - which many Norwegians associate with the vocal version performed by singer Sissel Kyrkjebø sitting on a polar bear made of "ice" during the closing ceremony of the Olympic Games in Albertville in 1992 - is only the tip of the iceberg. On Triptykon (1972) we find folk music infused pieces such as "Selje", "Bruremarsj" and more. On Dansere (1975) there is "Bris" and "Lokk". On Dis (1976) the exotic wind harp is an important instrument, recorded in the blizzard on Jæren, on Norway’s windswept weste coast. Nevertheless, it is understandable that the "mountain jazz" moniker has become an annoying itch. Only the "new age" stamp he sometimes gets slapped with on All Music and in reviews could be more stigmatizing.

Jan Garbarek. Photo: Guri Dahl

Jan Garbarek. Photo: Guri Dahl

This could very well be part of the reason he lays low, although it is probably rather due to personal and artistic temperament that Garbarek chooses to steer consistently clear of interviews, television appearances and award ceremonies. He is also known for being relatively inaccessible even to well-intentioned and respectful inquiries from younger musician colleagues and industry professionals. On the Norwegian jazz scene, there are those who believe he is thereby breaking some kind of unwritten law; that, as jazz elder statesman and living legend, he should be giving more back to the creative community he is part of.

He still plays concerts, with his regular band with Trilok Gurtu, Rainer Brüninghaus and Yuri Daniel. He is, nevertheless, not particularly productive, when compared to some of his peers and even older jazz colleagues. There have been a few records in recent times, including with the Hilliard ensemble, and his first concert album, a great recording from Dresden in 2006, as well as participation on a ECM tribute record to bassist Eberhard Weber. But Garbarek's last release with newly written original material under his own name, was In Praise of Dreams from 2004.

Afric Pepperbird provides ample documentation that an instrumentalist can create some of the most exciting and significant music of his career before he finds his tone - perhaps precisely because he is still searching. But to his critics, those who think he was «better» in this early, more playful, wild and exploratory part of his career, and who bemoan the fact he abandoned this form of expression in search of something different and more personal: One doesn't become what Down Beat critic Joe H. Klee in his Afric Pepperbird review called the most "original and forward-looking" European jazz musician since Django Reinhardt by imitating old role models. Paradoxically, that's exactly what Garbarek was doing when Klee paid him the compliment, but the American writer must have sensed where things were headed. Later, Garbarek was to establish a style so distinct and original that he has become one of the world’s few instantly recognisable instrumentalists. The brave move, then, was perhaps not to sound like a cross between Coltrane, Sanders and Ayler, but to stop doing so.

Translated and edited for clarity by the author. Session photos from Arild Andersen's personal photo album. Photographer: Unknown. Test pressing photos by the author.

Jan Omdahl is a Norwegian columnist, critic and author, writing about music, audio, technology, media and culture since the 1980s. He has published several books before this one, among them a collection of essays on the Internet, and the critically acclaimed biography of Norwegian pop band a-ha. He is a music freak, record collector and audiophile, in that order.

.png)