A SUPERSTAR IS BORN

On her first two albums Maria Dueñas tackles Beethoven, Paganini, and more

In 2023 Deutsche Grammophon launched its “Original Source Series” (OSS) of critically acclaimed recordings from the 1970s, cut for the first time directly from the 4- or 8-track original masters and remastered for exclusive release on vinyl only. The series, continuingly covered with great authority by my Tracking Angle colleagues Mark Ward and Michael Johnson, is so successful it has obscured the fact that for the past several years DG have also been routinely issuing simultaneous digital and vinyl versions of many of their brand-new releases, particularly of their headline artists: Yuja Wang, Hillary Hahn, Alice Sara Ott, Lang Lang, Víkingur Ólafsson, Daniel Trifonov, and the label’s latest sensation Maria Dueñas, not to mention reissues of albums not so recent, e.g., Festival, Gustavo Dudamel’s celebrated 2008 collection of orchestral pieces by composers south of the border, and Credo, from 2004, Hélène Grimaud's first Concept album. Of course, these are all digitally recorded, but so what?—everyone reading Tracking Angle knows digital sources often benefit from vinyl presentation. And like the OSS series, these LPs are limited in number and tend to sell out rather quickly, so if you’re tempted—well, forewarned as they say . . . .

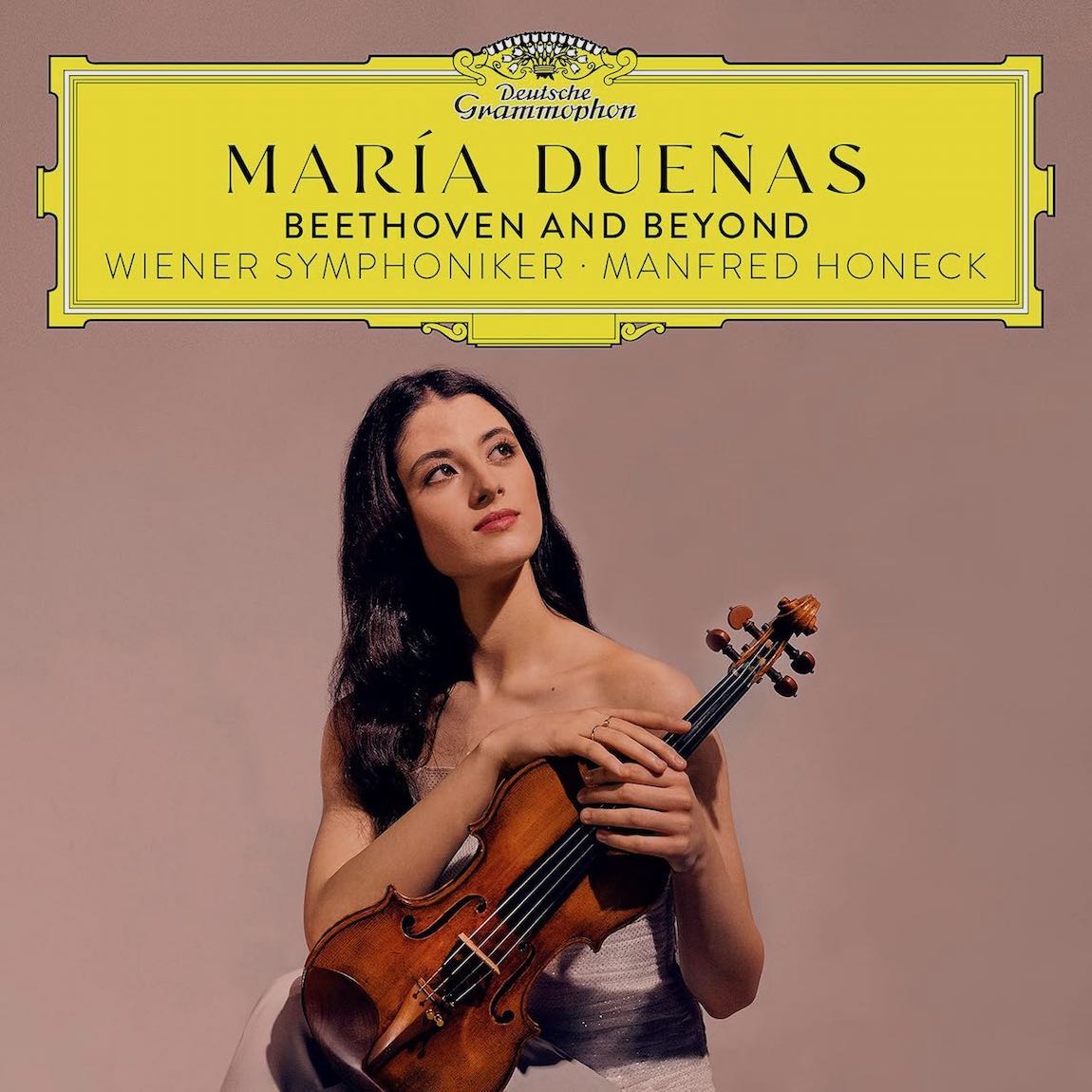

Beethoven and Beyond

Produced by: Rainer Maillard and Lukas Kowalski

Engineered by: Juan Mareno and Lukas Kowalski

Mixed by: Rainer Maillard and Lukas Kowalski

Mastered at: Emil Berliner Studios

Lacquers cut by: Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

(available on CD, 180g vinyl and streaming)

Music

Sound

.

Born in 2002 in Granada, Spain, Maria Dueñas began playing violin at the age of six, enrolling at the Ángel Barrios Conservatory in Granada; five years later she won a scholarship to the Carl Maria von Weber College of Music, one of Germany’s oldest conservatories; at fourteen she was in Austria being mentored by the distinguished Boris Kuschnir at the Music and Arts University of Vienna and the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz. She has placed first in some eight international competitions, including the prestigious Menuhin; by the time she was twenty, Deutsche Grammophon wasted no time signing her up, her maiden outing in what is still for me the most beautiful, also the greatest, of all concertos for the instrument, Beethoven’s, which she recorded, before turning twenty-one, with Manfred Honeck conducting the Vienna Symphony.

Her youth notwithstanding, the Beethoven has loomed large in her life from an early age. She started learning it “just for fun”; by the time she moved to Germany she had practiced it enough to play it for the conductor Marek Janowski, who told her that when she was eighteen he would conduct her with orchestra under his baton. “I was eleven at that time. So that became a goal, to play Beethoven at a high enough level to perform it with him.” A few years later, she was invited to audition for Herbert Blomstdet. “I played the concerto without accompaniment, not even a piano, because our meeting was unexpected and happened at the last minute. I just went onstage in the empty hall and played Beethoven for him.” (Right away he invited her to play the Mendelssohn concerto with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.) Meanwhile, the Beethoven was the last concerto she performed in concert before the pandemic and the first she performed after it, in 2021, under Janowski with the Dresden Philharmonic (three nights in a row).

Beethoven, age 34, circa 1806, when he wrote the Violin Concerto

Beethoven, age 34, circa 1806, when he wrote the Violin Concerto

I recount this brief history to make the point that this debut recording isn’t a matter of a major label exploiting a young artist by pushing her into sure-fire repertoire whether she’s ready for it or not. Indeed, when DG signed her they requested this concerto precisely because of her long history with it. She has really earned this recording. And she’s certainly got everything it takes to be both a superstar and a musician of the first order: imagination, intelligence, flawless technique, interpretive insight beyond her years, a temperament fiery and passionate yet graceful and lyrical, and a view of the work that is at once thoughtfully personal and highly individual without being in the least idiosyncratic or courting difference for difference’s sake. With a first movement five seconds short of 28 minutes (21-25 the norm) and a last movement that exceeds twelve (ten or fewer the norm), her interpretation is broad but never feels slow in the sense of plodding, heavy, or merely portentous, despite some very expansive phrasing and rubato, notably in the first movement, particularly in her trills, which she draws out to considerable length. Yet everything grows, flows, and surges in its own time, phrased with great sensitivity and beautifully inflected, by turns songful, even rhapsodic (her first and second entrances, the whole of the slow movement) and lyrical, her tone rich, glowing, full of color with absolutely no fear of vibrato, liberally yet always tastefully applied. (Her instrument is a Stradivarius "Composelice" of 1710.)

It’s an unapologetically romantic view of the work, generous of feeling, often large of gesture, and hardly without risk in these days of Historically Informed Performance (HIP) practice that insists on fast tempos, lean sonorities, and near chamber-sized orchestras. The Larghetto is rendered with great depth of feeling, ruminative in places, in others with a hushed intensity that makes me hold my breath. Beethoven didn’t supply a cadenza for the slow movement, but Dueñas adds one of her own, where to bewitching effect she subtly adumbrates the main theme of the third movement. The Rondo isn’t as bouncy and energetic as several other recordings in my collection, but it is marvelously festive in a way that makes it a natural and logical conclusion to the conception as a whole.

An early mentor of hers, a string player himself (violin and viola), and on the cusp of completing his own critically acclaimed Beethoven symphony cycle with the Pittsburgh Symphony (for Reference Recordings, the first from an audiophile label), Manfred Honeck not only is Dueñas’s full partner in this enterprise but is wholly supportive of and committed to her conception of the piece. In Pittsburgh (where he is the music director), he plays the symphonies with greater contrapuntal clarity, whereas in Vienna he coaxes a richer, more blended orchestral palate of a kind that sometimes invites metaphors like “well upholstered,” at once glowingly sonorous yet sculpted (I wouldn’t call it Brahmsian, though it certainly glances in that direction).

Like a number of younger performers these days, Dueñas is enamored of “Concept” albums, in which a number of different works and/or composers are brought under the same conceptual umbrella by way of contextualizing one another. Hence the Beethoven and Beyond title, “beyond” concerning the first-movement cadenzas. A composer herself, she has also supplied her own for the first and last movements (I like them all, especially how in the first one she always keeps a sense of the violin’s main melody before us even when she isn’t playing it literally—very Beethoven that). But she also plays first movement cadenzas by Spohr, Ysaÿe, Saint-Saëns, Wieniawski, and Kreisler, then programs a short work for violin and orchestra by each of them.

These shorter works are all new to me, so I can’t comment on them with any experience, except to say that I enjoyed them, especially Saint-Saëns’s Havanaise, a characteristic piece based on Cuban Habanera dance rhythms; Wieniawski’s Légende, a touching work the composer wrote in order to prove to the parents of a young woman that he was fit to marry her (it worked); and Kreisler’s Liebesleid, full of heartfelt Viennese sentiment, with which Dueñas identifies as if to the period born (I have a personal connection with this piece, as a recording of the version for violin and piano, Kreisler accompanied by Rachmaninoff, is featured in a scene in Ron Shelton’s movie Cobb, which I edited).

The only curious thing is the layout of the CDs. CD 1 contains the complete concerto and all the occasional pieces, CD 2 only the five additional cadenzas (around eighteen minutes total). Why didn’t DG engineers switch the cadenzas to CD 1, the occasional pieces to CD 2, and make it possible for home users to program each cadenza into the concerto itself? A missed opportunity.

The concerto was recorded live in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein, one of the most famous and acoustically beautiful of all the European concert halls. The sonics are appropriately golden, warm and inviting, with a wide dynamic range. My principal and practically only reservation is that the recording is just a tad close, with a corresponding flatness of perspective, the soundstage commendably wide but without appearing to extend very far back and without much space between the soloist and the orchestra (the violin sometimes spreads across the soundstage). One thing in particular I noticed is that the violin/orchestra relationship seems to me somewhat different in the last movement, more realistic with respect to balance, particularly in the interplay of the violin with the winds and horn, while in the closing tutti the orchestra overwhelms the violin, which is what usually happens in concert. Whether this owes to a different night with different miking—the performance is a composite from three nights—or manipulation at the controls, I cannot say.

Dueñas and Honneck performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein, where the album was recorded live.

Dueñas and Honneck performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein, where the album was recorded live.

I personally prefer the compact disc and the vinyl to the streaming option because they feel more solid and substantial. However, as between them, it’s a tossup. The vinyl has slightly more saturated tonal colors and a plusher lower end of the spectrum; the compact disc a bit more clarity, focus, and definition. Regardless, overall this is still excellently engineered, tonally quite opulent, with that difficult to define but immediately audible impression of live-music vitality. So let none of these observations deter you from buying the set in the format you prefer. I’ve been listening to this concerto since I was a junior in college, have acquired several recordings along the way (and listened to countless more); yet having listened to it now four times all the way through, I can’t think of one that has given me greater pleasure, few as much.

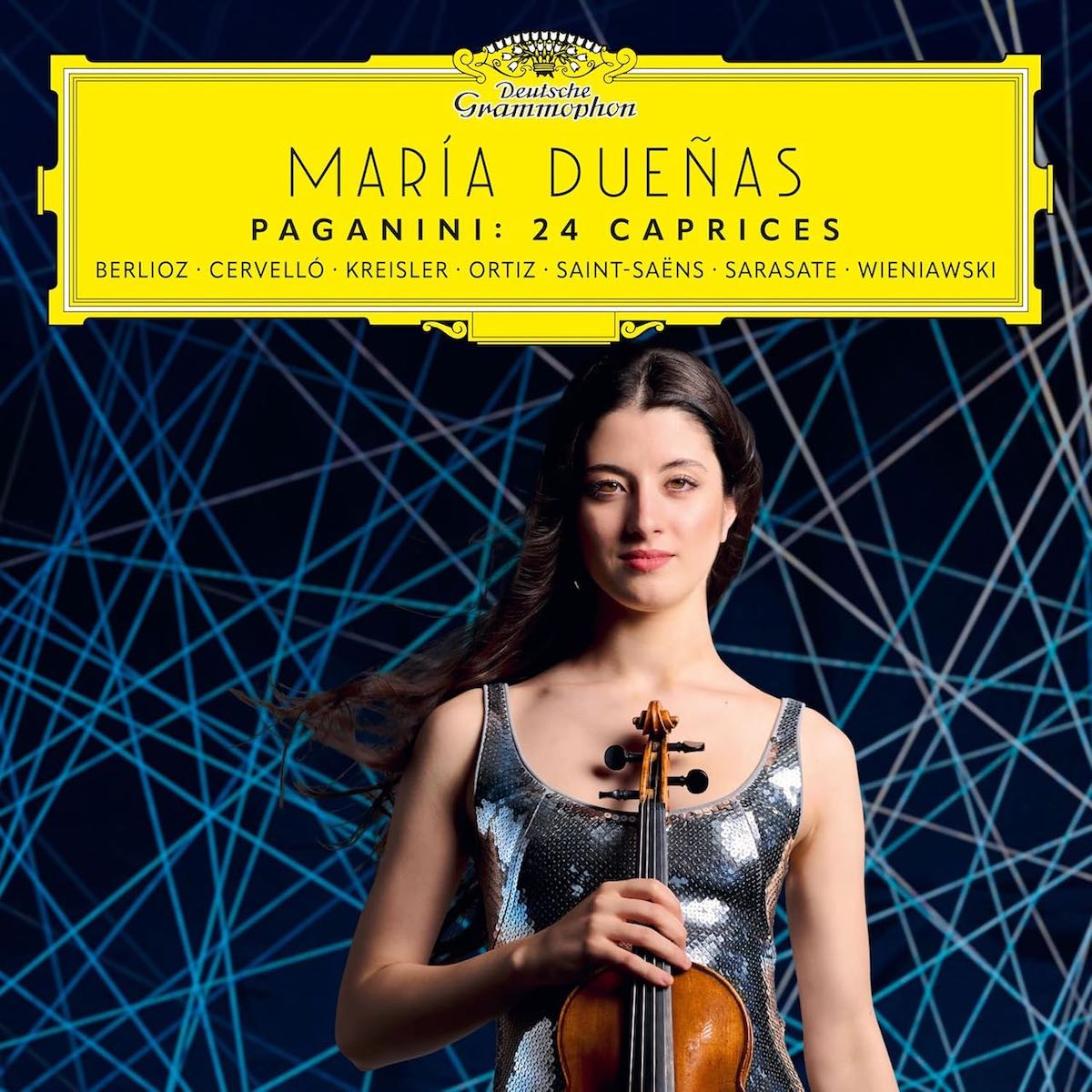

Paganini: 24 Caprices

Produced by: Alexander Grün

Engineered by: Alexander Grün

Mixed by: Alexander Grün

Mastered by: Martin Kistner

Lacquers cut by: Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

(available on CD, 180g vinyl and streaming)

Music

Sound

One of the joys I treasure most about reviewing for Tracking Angle and The Absolute Sound is the serendipitous discovery of either wholly new music or music that has been around for a long, long time but which I’ve never explored. Dueñas’s second album in her new contract with DG is one such: she tackles one of the Everests of the solo violin repertoire—by common consent the Everest when it comes to the techniques of playing the violin—Paganini’s 24 Caprices, the technical challenges of which are extreme, several of them requiring all but superhuman dexterity, flexibility, and strength in fingers, hands, and arms.

For decades following their publication, in 1820, several of them were considered impossible. It is said Paganini made some of them so difficult even he couldn’t play them, precisely to force himself to learn them so he could. Now, even the most difficult are practiced and played (or at least attempted) by all very good or better violinists, though fully mastering their most formidable technical hurdles, let alone mastering them in such a way as to make them at once seem effortless yet musically meaningful, remains an elusive goal that beckons many, chooses few.

Unfortunately, this has saddled them with a reputation that, though manifestly unfair, stubbornly persists in some quarters to this day: much technique, little music. I can’t recall if that is the reason I paid them little attention over five decades of classical music collecting and listening—the exception being, of course, the ubiquitous 24th, with its catchy opening tune that’s been appropriated by so many composers (most famously in variations by Brahms and Rachmaninoff). As for the rest, while I have many recordings of Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas and partitas, and a couple of Ysaÿe’s sonatas for solo violin, I have none of Paganini’s Caprices despite the availability of dozens of complete sets and hundreds of individual selections.

So when Dueñas’s arrived I figured I’d begin by sampling a few. After all, though Paganini published them all together as Opus 1, they were composed over the decade between 1807 and 1817, in groups of five, seven, and twelve (or six, six, and twelve). Neither before nor after publication did he ever perform them in public, and there is no hard evidence he played even a few of them in private gatherings for friends. It is conjectured he published them only so that other violinists would attempt them, come a cropper, and thus reconfirm his reputation as the greatest violinist the world had ever known. And so protective was he of his virtuosity that he refused to play the solo parts of his concertos in rehearsals with orchestras because he didn’t want his innovative techniques to be imitated.

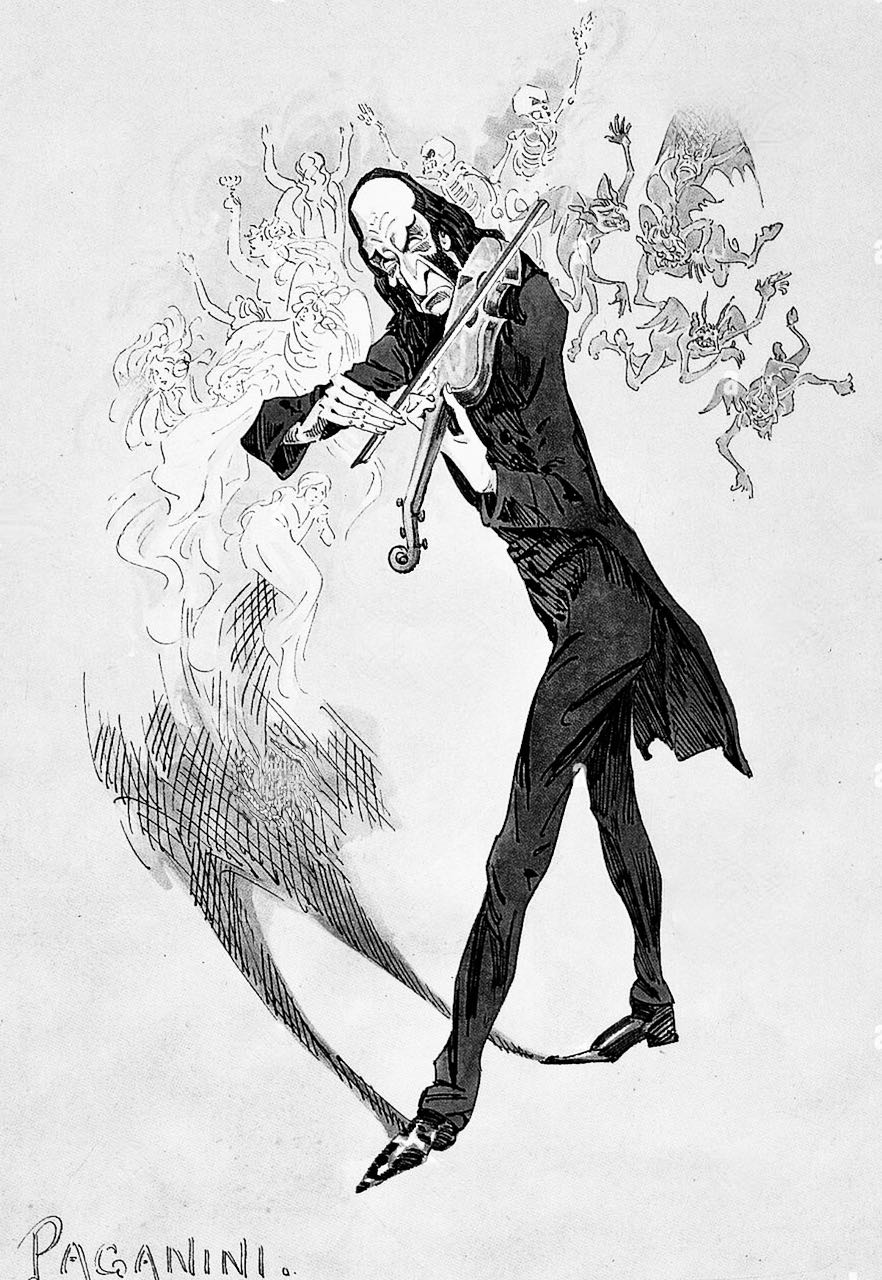

Paganini generated such excitement with his virtuosity that members of the audience often fainted at his concerts.

Paganini generated such excitement with his virtuosity that members of the audience often fainted at his concerts.

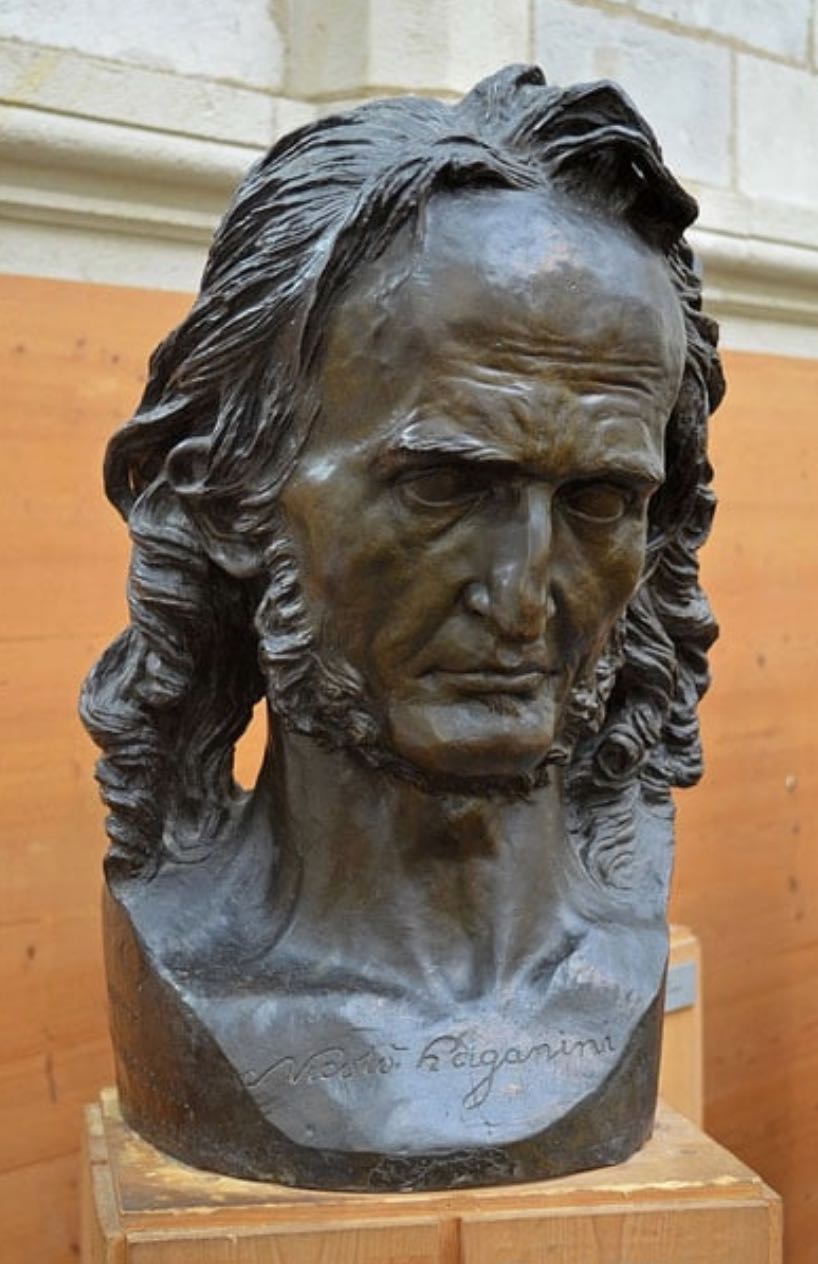

In fact—a brief historical digression here— Niccolò Paganini was history’s first superstar, musical or otherwise, and he set the pattern for the lifestyle that continues to this day among rockstars, pop singers, and other celebrity entertainers: sybaritic behavior (much womanizing, addictions to alcohol and gambling), high fees (his tickets cost twice and more than those of any other virtuoso performer), extravagant showmanship (he would arrange for the strings on his violin to break one by one so he could finish on a single string, which usually brought the house down), carefully cultivated image (tall, thin, gaunt, pale of skin, he often dressed in black, which, in combination with his other behavior, did little to dispel, much to reinforce the widely held belief that he actually did enter into a Mephistophelian bargain to sell his soul in return for fame, fortune, and God-like artistry), and charisma that held audiences spellbound (after the triumphant Paris performance of his fourth violin concerto, the French critic Castil-Blaze reported that “several members of the audience fainted with excitement”). Lionized though he was throughout his life, including intense admiration not just for his playing but for his music by such luminaries as Rossini, Schubert, Berlioz, Schumann, Chopin, and Liszt (so awestruck by his playing that he was inspired to advance pianism to the equivalent level of virtuosity and expressiveness), when he died it was five years before the Catholic Church would allow him to be buried on consecrated ground owing to the legend of his bargain with the devil.

Tall, slim, gaunt, pale, attired in black, Paganini's carefully curated image encouraged the belief that he had sold his soul to the devil in return for God-like skill and artistry on the violin.

Whatever else, though, it’s doubtful Paganini ever intended or imagined all twenty-four caprices being played or listened to in a single sitting. So as I say, I sat down, late of a typically cool but sunny Southern California spring afternoon, and cued the first side. Before I knew it, over a hundred minutes had passed, the stylus was locked spinning in the lead-out groove, and I was glued to my listening chair, by turns enthralled, enchanted, entranced or delighted, thrilled, exhilarated, or—well, let's just say generally all around gobsmacked! I repeated this experience two more times in the coming weeks, each time more exhilarated, first by novelty, then by increasing familiarity. One of these was with a close friend, a fellow audiophile, a member of my informal listening group, who, like me, has listened to classical music his whole life yet never paid much attention to Paganini. He, too, was similarly gobsmacked and acquired the set right away.

We discovered what countless others before us already knew: Paganini may have composed these pieces as studies for himself and other violinists to develop and advance their skills, in the process extending the expressive and technical range of the violin beyond anything anyone imagined before him. But he called them, not etudes or preludes, rather “caprices,” a musical form that goes as far back as the sixteenth century and refers to pieces that are typically free in form, mercurial in mood, unpredictable in temperament, often characteristic (i.e., evoking an individual or specific character, attitude, or mood), typically light and lively (though not always), and usually short (the shortest well under three minutes, the longest around eight).

What I was wholly unprepared for is how fantastic these pieces are, a descriptor I use in the sense of its original relationship to “fantasy”: evocative of dreams, of magic, of reverie and romance, and also of the phantasmagorical, the strange, the eccentric, occasionally even the weird, not to mention emotion, delight, humor, wit, whimsy, and playfulness. They’re also addictive. Since this set arrived over a month ago, I’ve taken as deep as dive as time would allow into this particular recording, other recordings (too many to count), Paganini himself, and violin playing. I do not play the violin, but I am fortunate in having a close friend and fellow audiophile in Peter Kent, one of Los Angeles’s top studio violinists (which automatically makes him one of the top studio violinists in the world). Peter joined me for several listening sessions during which he schooled me on the music and the playing in ways only a professional who practices daily, as he does, always including a few of the Caprices, could.

Bust of Niccolò Paganini made circa 1830-33, when he was around 50, by David d'Angers

Bust of Niccolò Paganini made circa 1830-33, when he was around 50, by David d'Angers

This is the point at which it is probably most prudent, not to mention honest for me to stop now, being still new to this music and still flush with wide-eyed discovery and, frankly, thoroughly besotted ga-ga amazement. That said, I beg indulgence for three observations, perhaps permissible because entirely subjective and indicative of early enthusiasm.

First, even if your experience of violin playing is fairly rudimentary, it’s perfectly obvious that the fiddling here is at a level of mastery that is rare indeed, even among stellar virtuosos. Examples abound in every one of them, but go to 5, with what Charlotte Gardner, whose eloquent rave in the April Gramophone first alerted me to this release, aptly calls the “blizzard of ricochets” in its middle section. Ricochet means bouncing the bow off the string, to which Paganini adds several crossings, which jack up the difficulty exponentially. Or the first, with its multiple stops and arpeggios (when I played this for my wife, she exclaimed, “How expressive her playing is!”). Or the last, where I gasped the first time I heard how powerful, even explosive are her left-hand pizzicatos in the ninth variation—which I mentioned to Peter, who said, “Yeah, they’re astounding!”

Second, take what I’m about to say next for what a tyro’s perspective may be worth, but in the comparisons I found I usually preferred the sound of her violin, a Nicolò Gagliano violin circa the 1770s, over what I hear in many others: tonally richer in the lower strings, with a lot of contribution from the body itself (a characteristic, according to Peter, of this violin maker), brilliant on the upper ones, from which Dueñas produces a kaleidoscopically dazzling range of color, sonority, touch, and dynamic shading, a variety directly mirrored in her gloriously variegated interpretive approaches to and characterizations of the individual numbers.

“In Spanish, caprichio means taking a liberty with something,” Dueñas says, “anything from food to music.” She is not only supremely attuned to how different the Caprices are from one to another, but is breathtakingly, fearlessly responsive to how quickly, often radically, occasionally violently mood, attitude, and temperament can turn on a dime within each piece. She revels in their constantly shifting landscapes. 20, for example: how sinuously she phrases the melody in the A section before aggressively launching into the B section where at 4:25 she makes you think you’ve wandered into Bartok territory with an ensemble of strings. Or 4, perhaps the most melancholy of the twenty-four, where she goes to the heart of what she perceives as “a sense of pain running through it.”

Classical and early romantic composers delighted in making solo instruments imitate other instruments, a delight Dueñas clearly shares, whether flutes and horns (9), trumpet (14), post horn (18), and, my personal favorite, a bagpipe in 20, where the D string produces the drone, while the A and E strings in imitation of chanters weave a lovely undulating melody, her performance so exquisite I think I played this one every time I listened to the set piecemeal.

And the forbidding 24th, surely the most tightly compressed and mercurial set of variations in the history of music? Paganini works his famous tune through eleven variations plus a finale all in the space of plus-four to plus-seven minutes, Dueñas at the outer end of the range. Peter and I listened to several performances one afternoon via Qobuz, after which I remarked that most of them seemed to me faster than Dueñas’s. He replied, “Yeah, well, there are a lot of violinists who try to set speed records with this music, which I don’t necessarily care for. What she is doing is much harder, because it involves a longer stroke, which requires more control. Her control is phenomenal!” To my ears she shapes these variations into a narrative, a kind of odyssey if you will—and no, I can’t translate what I mean by that into paraphrasable terms, only that it is how I hear it, how it feels to me. As it happens, well after I had formed this impression, I came across an interview where she calls it “a showcase for everything one can go through in a lifetime, showing just how much Paganini developed as a person over the four or five years it took him to reach this final caprice in the series.”

"Here, Paganini combines everything that we already had in the previous caprices: double stops, wild bowings, cantabile moments, sad moments, nostalgia and plenty of furious passages."

"Here, Paganini combines everything that we already had in the previous caprices: double stops, wild bowings, cantabile moments, sad moments, nostalgia and plenty of furious passages."

Third, by her own admission, Dueñas is very much aware that Paganini loved opera and that he lived in the time of bel canto. As in the Beethoven concerto, her cantabile playing, her legato feels less played than genuinely sung. Try 11, of which she says, “As a violinist, you need to be able to switch quickly from one character to the other, but also to sing every note, even in the fast and virtuosic passages. This is a challenge, yes, but a good one.”

Unlike her Beethoven debut, Dueñas spent a whole year in the studio making this album, yet it never feels calculated or self-conscious. Like the pieces themselves, she’s everywhere spontaneous, impetuous, unbridled, impulsive, sometimes even reckless yet without ever losing control. Even better, she often sounds like she’s having fun (try 13, "The Devil's Laughter," where she teases just a hint of sleaze out of the melody).

Like Beyond Beethoven, this too is a Concept album, in which Dueñas includes seven caprices by other composers who came after Paganini, continuing right up to the present. Sarasate’s Caprice Basque is for violin and piano (Itamar Golan, Dueñas’s longtime pianist collaborator); Cervello’s Milstein Caprice for solo violin was written especially for Dueñas because her playing reminded the composer of the great Nathan Milstein’s; on Wieniawski’s Etude-Caprice for two violins Dueñas is joined by her mentor Boris Kuschnir; Gabriella Ortiz, who wrote her violin concerto Altar de cuerdo for Dueñas in 2022, contributes De duerdo y madera for violin and piano (Alexander Nakifeev partnering), composed expressly for this album and Dueñas, here receiving its world premiere. Two capriccios by Saint-Saens and one by Berlioz, all for violin and orchestra, complete the program, Mihhail Gerts conducting the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin. As with Paganini’s Caprices, these too are entirely new to me and I enjoyed them all.

Released on CD, streaming platforms, and vinyl, the superlative sonics are some of the most beautifully recorded violin sound I’ve ever heard, the relationship between proximity of microphones and room sound ideal. The violin is front and center, bold and immediate, and so colorful I played it louder than usual because the music and the playing are so involving I wanted to make the experience as immersive as I possibly could.

And, yes, though the margin is not huge, I have to say that I liked the vinyl best of all: more organic, more lifelike, with a greater sense of bloom, vitality, and reach-out-and-touch it tactility. And though the compact disc and streaming have plenty of warmth and dimensionality, the vinyl has a bit more, with, like the Beethoven, blissfully quiet surfaces. When asked about vinyl in a recent interview, Dueñas said, “I have a very large vinyl collection. I like listening to vinyl, especially!” The one oddity is that only the 24 Caprices are on vinyl; the rest of the pieces are on a compact disc included in one of the gatefold jacket’s sleeves. Presumably DG wanted to restrict this to a two-LP set for reasons of pricing. Don’t let that deter you, the digital sound is just fine and I would not feel in the least deprived if that’s all I had.

Nearly all the way through June as I prepare to post this review, Dueñas’s 24 Caprices is on every level the most exciting new album I’ve heard so far this year. And though I am wrapping up the review, I am far from finished with these spellbinding miniatures, which I shall go on exploring and enjoying as long as I listen to music. I could scarcely have imagined a more persuasive, compelling, and spectacular introduction than that provided by this prodigiously gifted young artist.

Listening and Watching

Here is a BBC interview where Dueñas identifies her seven favorite Paganini Caprices, with links to YouTube videos of her playing the 5th and the 24th, the latter in an excellent MTV-style promotional video DG created, in which thanks to the wizardry of moviemaking she manages the nifty trick of a wardrobe change in the instant it takes to cut from one shot to another!

Here is a BBC interview where Dueñas identifies her seven favorite Paganini Caprices, with links to YouTube videos of her playing the 5th and the 24th, the latter in an excellent MTV-style promotional video DG created, in which thanks to the wizardry of moviemaking she manages the nifty trick of a wardrobe change in the instant it takes to cut from one shot to another!

.png)