Apple To The Corps

Month by month history on the early days of Apple Records

“As we told you on the phone, Apple Records is not interested in signing David Bowie.”

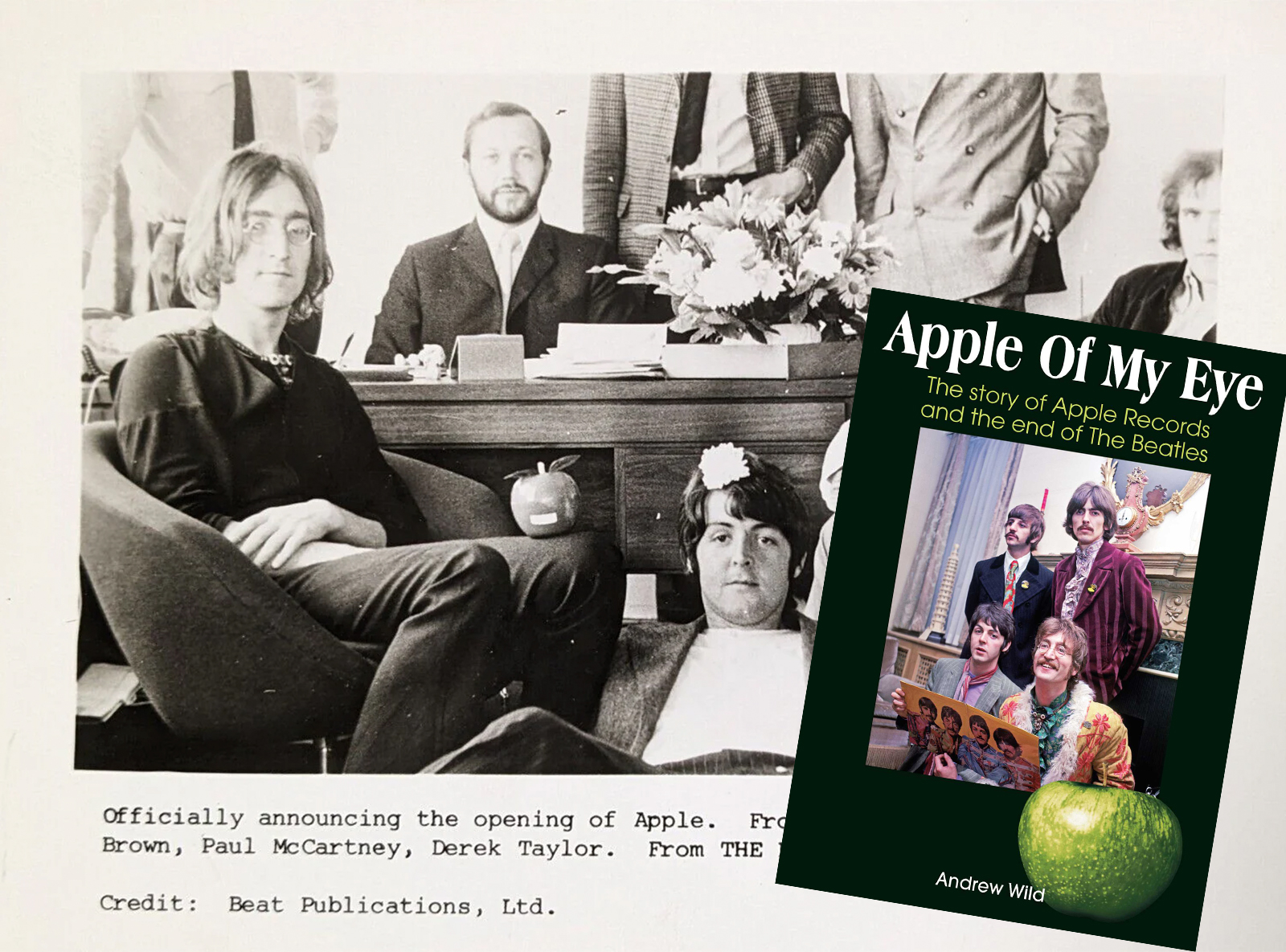

But then again they weren’t the only ones. That said, that was just one data point in the now legendary mess that was the early days of Apple Records. Because as Andrew Wild points out right at the top end of his “Apple Of My Eye” book, The Beatles seemingly impractical scheme to reinvent the music world spawned 21 top ten albums in the UK between ‘68 through ‘76 and an equally impressive 24 chart smashes in the US during the same period. But these not inconsequential triumphs couldn’t offset the difficulties the band and their associates leapt out in front of at nearly every turn.

Across 139 pages Wild takes a month-by-month ride through all the ups and downs taken by of one of the world’s most high profile yet infamous labels. In some ways it reads like a chronicle of inspiration and in others like a travelogue to ruin. If you want to know why Mary Hopkin recorded and then largely shelved her cover of “Que Sera, Sera,” it’s noted. If you’re at all curious why you’ve never heard about Lon & Derreck Van Eaton’s “Brother” LP from 1972, despite Rolling Stone calling it “…staggeringly impressive,” the details are here.

Once you’re a dozen or so pages invested, what’s eminently clear is that the file on Apple Corps early existence could have been stamped “Chaos” and put back in the drawer. Between managing their own affairs, trying to make good on their global promise to not just be another walled off corporate garden, and recording material that could possibly change the world of popular music, when it came to business The Beatles were simply dilettantes. But far worse than being inexperienced was their underlying resistance to appear…uncool.

One particularly glaring example of this comes up following the resignation of their accountant and financial adviser Stephen Maltz in October 1968. Following an excerpt from Maltz’s 2015 memoir where he outlines just how bad things are financially for the Fabs, Wild includes a very telling quote from Lennon:

“(Apple General Manager Alistair) Taylor explained that Apple was losing £50,000 a week. ‘If you allow things to carry on the way they are, you will lose all of your money within 12 months,’ he told The Beatles. Lennon’s response: ‘Don’t be a drag, Al.’”

What the book does particularly well is create a timeline that snakes in and around the company’s successes and disasters and highlights the music that managed to escape Apple’s dysfunction. In fact .if you built a playlist off the rolling discography presented in each chapter you’re bound to discover gems (big and small…) that were previously unknown. How else might one come across the upbeat boogie soul of “God Save Us” by Bill Elliot & the Elastic Oz Band? And while it’s interesting to note all the artists they opted not to sign (Fleetwood Mac, Joe Walsh, Yes, and 10cc for starters…) the extended anecdote here of how they passed on the first Crosby, Stills and Nash record after being given a live audition of the trio’s material is almost beyond belief.

With a variety of accounts from insiders to savvy onlookers, this is in no way the only in-depth look at Apple Corps’ notable infancy. The difference between this and the handful of other books that have touched on the dynamism and the rot of Apple Corps is that Wild’s tome if mostly matter of fact and free of the internal vibes that drove the enterprise. It’s written as if he were assembling a ledger – adding context to the label’s moveable feast until it becomes the sad buffet that finished out its initial run of singles with George Harrison’s “This Guitar (Can’t Keep from Crying).”

///

Interview with author Andrew Wild

Tracking Angle: You’ve done other Beatles related titles in the past (“The Solo Beatles, 1969-1980"; "The Beatles 1962-1966: Every Album, Every Song"), but how hard was this one to put together?

Andrew Wild: So, there are two types of book that I write. [snorts] One would be what I might call just desk research. So, plotting a timeline and then filling in the details and then reading lots of books and finding quotations and then doing that. “Apple Of My Eye" was a suggestion by my (Sonicbond) publisher. He said, "No one's really written a book that goes into the depth…not only of the business side of Apple Records, but the actual music, the singles and the albums that they've released by the various different people on it." So, I said, "Yeah, that sounds sounds fun. We'll do that." And that was what that was a desk research project. I didn't need to interview anybody for it because the central people to this story wouldn't be interested in talking to me anyway. So it becomes a kind of a more personal view of starting with a timeline from 1967 and going through to 1976 when Apple kind of finished and almost going month by month of who was recording in this period, when were the records released, how successful were they, and did they hit the charts or not. And then embed that with as much information as possible without getting too bogged in the detail of why did Apple exist.

TA: What was immediate to me was that I saw you were taking what happened month by month, which is nice because it's such a convoluted story.

AW: I wanted to get the context in that this book is principally about the music that was released on Apple Records. So Badfinger, Mary Hopkin, the Beatles solo albums, John Tavener who is a classical composer, the Modern Jazz Quartet and these other strange ideas. So my principle here is to try and understand how these musicians and these albums were firstly came into the orbit of the Beatles. And secondly, whether the music actually holds up 50 or more years later.

TA: Would you agree that one of the chief takeaways from this story is that maybe The Beatles could only be faulted so much for what happened because, even though this is already 10 plus years into the rock and roll era, they were still learning a lot about things as they went along?

AW: Absolutely right. And Apple was formed as a tax shelter originally. (Their manager Brian) Epstein figured out that corporation tax, that is paying tax as a business rather than an individual is significantly less. So they worked a way to funnel all of the Beatles royalties through Apple Records, and the various Apple subsidiaries, which could then be written down against tax and the Beatles individually come back with better income. But what ultimately happened is that the spending within Apple was utterly and completely out of control. There's a famous story that the mail boy who would deliver the letters every day at the Apple offices would then go up to the roof and strip off all the lead and take it away in his mail bags and sell it. Televisions would disappear, cars would be bought and no one would know where they went.

.png)