EBS Reissues BBB AAA

The Original Source titles released this month are yielding quality performances and quality remasterings

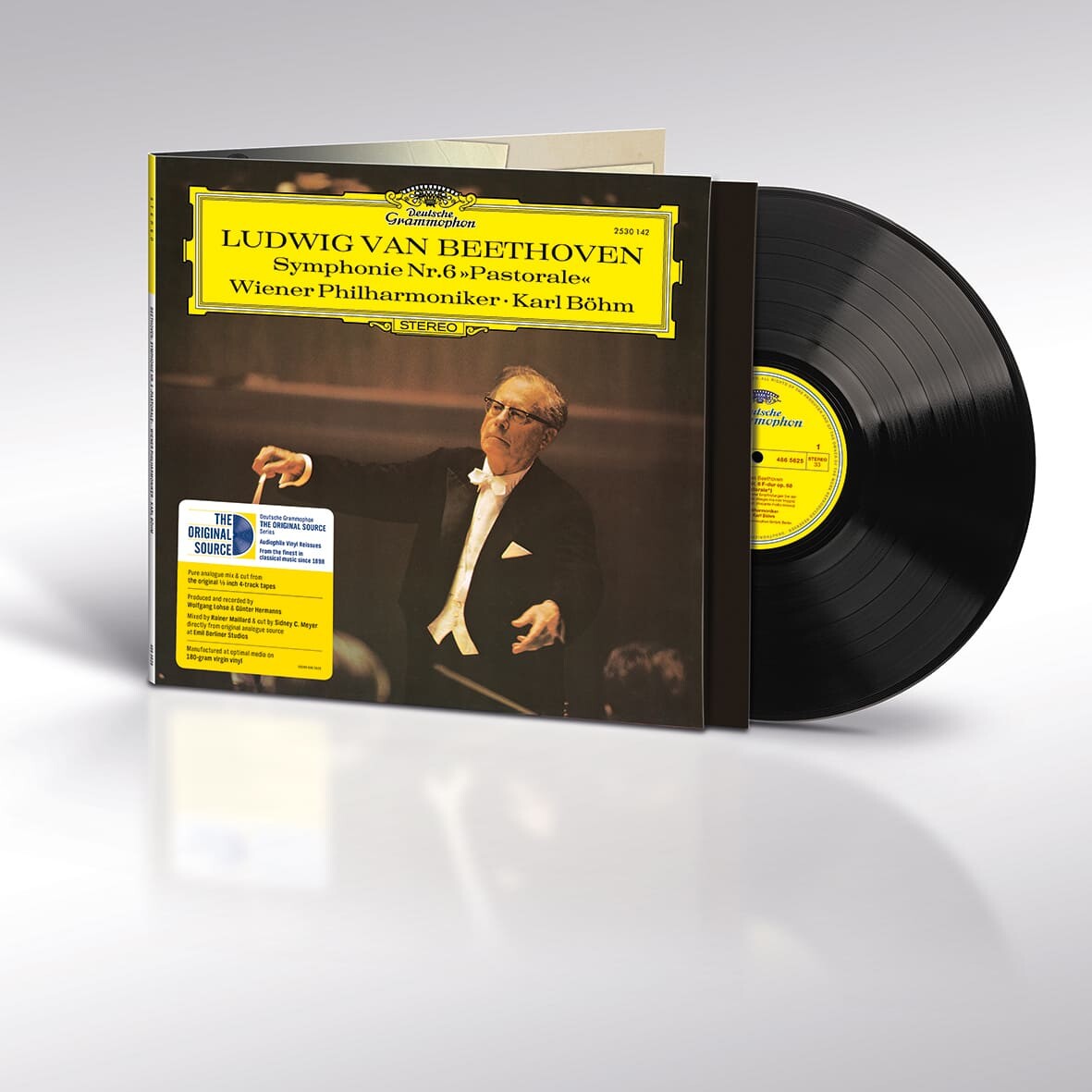

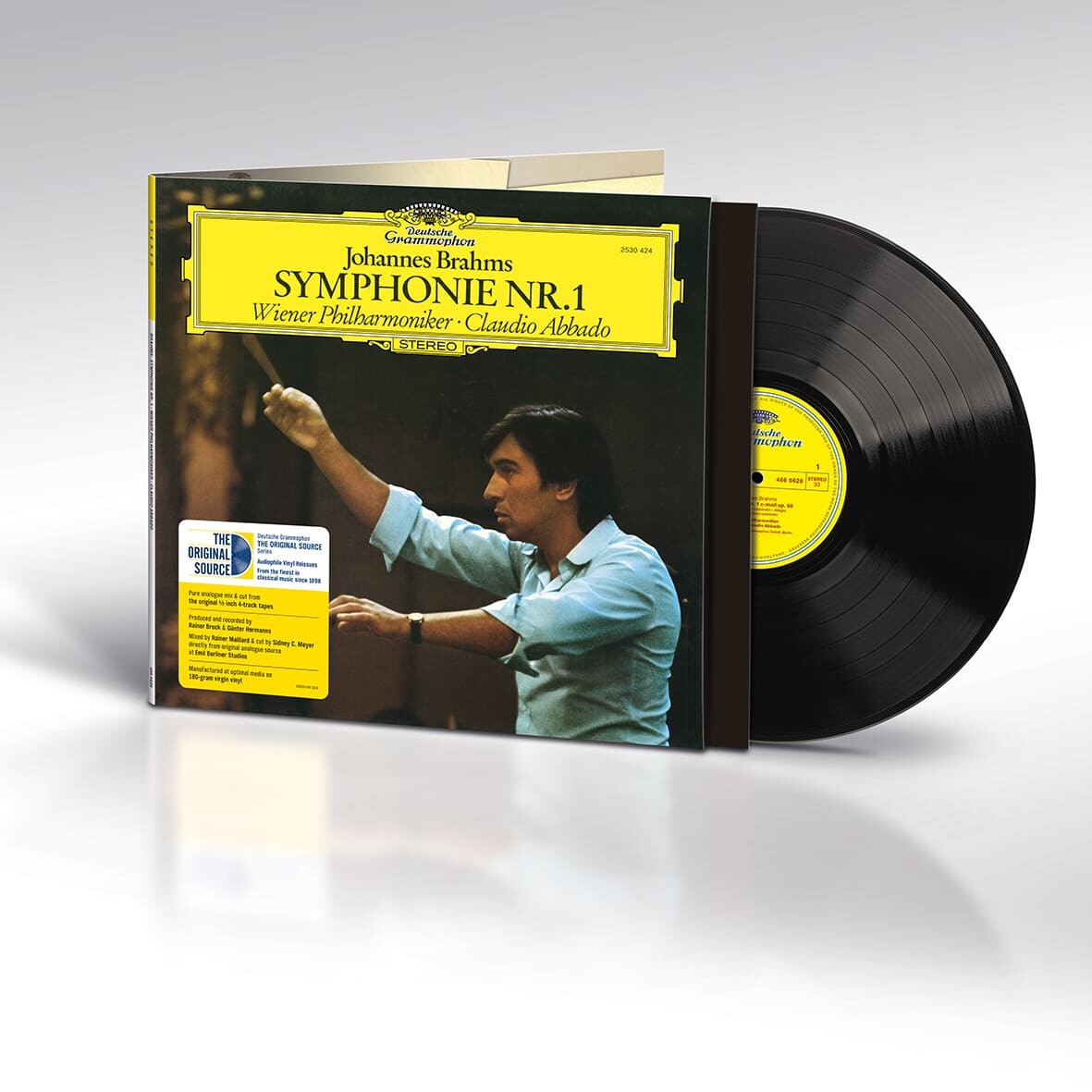

After spending my previous article gushing over Barenboim’s sonically thrilling Bruckner 4, we’re left with the three remaining Original Source titles for this month, which are some of the most “meat and potatoes” repertoire we’ve seen so far. Any decent classical record collection is going have a copy of these three works: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, Brahms Symphony No. 1, and Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. They are frequently recorded and performed cornerstones of what we for better or worse, call the “canon” of western orchestral music, and each represents the height of their respective periods of artistic style. Beethoven 6 of course, represents the composer at the peak of early German romanticism (a style Beethoven was instrumental in establishing), Brahms represents the middle of the timeline of romanticism being premiered in 1876, while Bartók’s Concerto is more or less a send-off of the late-romantic orchestral style, blended with modernist tonality and folk music elements. These three works chart over the course of 140 years the sunrise and sunset of the large orchestral symphony.

Because these works are so often recorded, these records have some stiff competition for performance and sonics, and I will try to cover some of those on each piece. But there is good news, these are some of the most sonically consistent Original Source releases I’ve encountered so far, and it means things are only looking up for the reissue label.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s (1770-1827) Symphony No. 6 in F Major “Pastorale” was premiered in Vienna in 1808 in an infamously poorly-received concert where the well-known Symphony No. 5 in C minor was also premiered. The symphony is one of Beethoven’s few explicitly programmatic works (music which is meant to portray specific scenes, events, or stories). It is also the only even-numbered Beethoven symphony that is regularly programmed (the often-performed symphonies are 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9). The “Pastorale” is one of the key works prompting the trend of German romantic composer’s obsession with nature and naturalism. Composers often found inspiration in nature, particularly because it represented both social escape, but also mysticism and the unknown. This concept would be explored thoroughly in operas like Weber’s Der Freischütz, and of course Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. Beethoven’s work is inspired by his long walks through the countryside in the summer months, escaping the noise and inconvenience of city life (and in some respects, the harsh realities of his ongoing hearing loss).

The sixth symphony’s five movements each carry a subtitle:

I. Awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the countryside

II. Scene by the brook

III. Merry gathering of country folk

IV. Thunder, Storm

V. Shepherd's song. Cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm

One can tell somewhat by the titles of these movements, and perhaps by the placement of this work in the key of F Major, that this is one of the composers most joyous and lighthearted major works, a stark contrast to the seriousness of the Fifth Symphony. Even the violent fourth movement Thunder, Storm resolves into a sunny daybreak in the fifth movement. If you think of Beethoven as primarily writing anguished music, I highly recommend you give Symphony No. 6 a try, it will show you another side of ol’ Ludwig.

There are lots of excellent performances of this joyous symphony on record. The one I have always reached for is Columbia MS 6012, a 1958 stereo outing of Bruno Walter conducting the Columbia Symphony. That performance is correctly revered, and is thankfully available in both 33 and 45rpm versions from Analogue Productions. On it, Walter gives one of the best performances of his high-fidelity career, and it’s no wonder that it is one of the only classical Columbia titles Chad Kassam has ever chosen to reissue. There’s also a remarkable 1959 reading by Pierre Monteux on gorgeous RCA Living Stereo (LSC-2316) also with the Vienna Philharmonic, that has sadly not been reissued, but is not too expensive to find in its original shaded dog format.

The version in question here has some of the best sound I’ve ever heard from a DG Bohm recording, with taut low end from the pizzicato low strings, and impactful transients from the timpani strokes in the storm movement. Strings have a lovely tone and body to them, and the Vienna woodwinds shine with their unique tonal color (Vienna woodwinds are unique in that they largely still retain the same types of instruments played on in the mid 19th century). I wish I could directly compare the wonderful Walter and Monteux performances on record but alas I believe those two albums are still sitting unpacked somewhere in my parents’ basement.

I was however, able to compare this new Original Source pressing to a relatively recent AAA reissue of the same recording from Pro-Ject records thanks to the generosity of our own Mark Ward. The Pro-Ject version released in 2019, is remastered from “the original tapes” and is all analogue, but I suspect the original tapes in question are an older stereo mixdown of the 4-track masters. One point the Pro-Ject version has over the new Original Source pressing is that is spreads the music out over two LPs (with the 4th side occupied by Beethoven’s “Egmont” overture). However, it seems Emil Berliner is doing something right with these 4-track remasterings because its version handily beats the Pro-Ject. There is much more information presented to the listener, greater detail felt, especially in the high register where strings have greater air and harmonics. The difference in mix and master are especially felt in the horn calls of the movement 3: Allegro, where the attacks have a three dimensional body too them, rather than the somewhat soft and mellow entrances portrayed on the Pro-Ject version. The fourth movement “Storm” is also a victory for Maillard and Meyer as their cut has far greater dynamic slam, imaging, and bass speed.

My advice: this is a top performance with the Vienna Philharmonic at home in repertoire they excel at. Yes, the Walter is also in-print and one of the critical darlings of this piece. I can’t tell you which one to buy, I wouldn’t want to be without either (and will be digging to look for my copy next weekend), but if you select this excellent Original Source pressing you won’t be disappointed in any category.

Music: 10/11

Sound: 9/11

If anyone has often been considered the “heir” to Beethoven’s musical legacy, it is German composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). In fact, fellow romantic Robert Schumann declared as much publicly in the beginning of the young composer’s career. Despite the great expectations hoisted upon him, Brahms did not debut his first symphony until 1876 at the age of 43. Brahms’ first attempt at a symphony actually morphed into his Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor. And his next attempt took him some fourteen years! Brahms was his own harshest critic and he was constantly reworking and destroying his own sketches. The comparison to Beethoven seemed to be both a blessing and a curse to Brahms, because he constantly felt the weight of not living up to his legacy.

However the work, in the public’s eye, appeared to be worth the wait, as contemporary critics lauded the formalism of Brahms composition, even calling it “Beethoven’s Tenth”. The opening actually begins with a formal introductory section, heralded by thunderous timpani strokes. The movement then settles into a traditional sonata form, and this is the real distinction in Brahms’ music as opposed to his contemporaries at the time; Brahms kept and expanded the formal structures of the classical and earlier romantic eras. This was in contrast to newer compositional trends emerging in Germany at the time, particularly the through-composed works of Richard Wagner who was considered the much more radical and new musical voice of the time.

All that said, Brahms’ music does have its own voice, and that is one of intense expression and melodic lyricism. To understand this, all one has to do is listen to the soaring and sublime melodies of the second movement ‘Andante sostenuto’ to hear the composer’s keen ear for melodic development, up there with the sublime arias found in Mozart’s best operas. The fourth movement ‘Adagio-Allegro non troppo ma con brio’ is where we really catch a glimpse of the composer’s expertise in form and orchestral richness. The main theme which enters in the exposition after the introduction is one of the most grand melodic lines in the repertoire, and in many ways harkens to Beethoven’s “Freude” tune from the Ninth Symphony. The development of this theme however is quite a bit more advanced than Beethoven’s, and it’s easy to get swept away following all the individual fugal lines this melodic content brings forth. It’s easily the best movement of the piece and if you’ve never heard a Brahms symphonic work before, this will be sure to rope you in.

I own far too many versions of this symphony, and despite that, no version has ever really blown me away in all aspects. The one closest to me personally is George Szell’s 1957 recording with the Cleveland Orchestra on Epic Records (BC-1010). This is more or less the recording I grew up listening to, and it is one of the most musically satisfying versions I’ve heard. Unfortunately, these Szell recordings with Epic/Columbia just never sounded very good. A few years ago this LP was reissued by Speakers Corner records with greatly improved sound thanks to Kevin Gray’s remastering job from the original Epic master tapes. However, compared to other versions I own, this recording still doesn’t quite cut it in the audiophile department. That doesn’t matter as much to me though, because the playing by the orchestra is bar-none in so many respects, with some of the best oboe playing I’ve ever heard from then-principal oboe Marc Lifschey. Szell’s interpretation is taut and refined, he’s a control freak, but one that has a deep understanding of the musical form.

One very good sounding version I own is an early 1961 Karajan "Living Stereo" recorded by the Decca team with the Vienna Philharmonic (LSC-2537). Actually, I own it as part of a somewhat rare Living Stereo “Brahms Symphonies” box set (LSC-6411) which I found years ago at the old Amoeba Records on Sunset Boulevard. This version has the trademark lush living stereo sound that gives the violins and violas a three dimensionality other recordings just can’t touch, even if the soundstage is a bit more opaque and the overall orchestra comes off as a little dark. Karajan’s interpretation is the opposite of Szell's, and the performance is slower and a bit more indulgent of musical lines. The Vienna winds are also greatly softened here, as opposed to Cleveland where they sing out with vibrancy, and there are some intonation issues not found in the Cleveland reading. But, this is very nice sounding LP full of color that is definitely worth tracking down, it’s very similar artistically to Karajan’s much more well-known 1960s Brahms cycle with the Berlin Philharmonic on DG.

Speaking of that Karajan/Berlin Cycle; Emil Berliner actually reissued that classic box set in 2017 (0289 479 7429 1), cut from the original tapes by Rainer Maillard. This version is very similar in interpretation to his earlier Vienna performance, however I would say the playing is of a bit finer grade (intonation for instance, is much better here). Sound is more dynamic with much fuller and faster bass than the "Living Stereo", although the strings sound rather hard and occasionally almost screechy, as is the case with many DG recordings. It’s definitely not as “lush,” but what you trade for that is detail, soundstage, and slam. In many ways this mastering is very similar to the Abbado EBS cut, which I will of course be getting to. It’s a shame that this Brahms cycle box set is out of print and considerably rare now, because this is really one of the “standard” “go-to” Brahms symphony cycle recordings. Deutsche Grammophon should really do another run of these, I would assume the plates are still in very good condition considering only 2250 boxes were produced.

Are there other great versions I own? Sure, there’s Kubelik with Vienna on London Blueback (CS 6016), Solti’s complete cycle with Chicago also on London (CSA 2406), and Maazel with Cleveland again on London (CS 7007), Horenstein with the LSO on Quintessence (PMC 7028), the artistically excellent but sonically disappointing Walter with Columbia (MS 6389) and then of course there’s one of the rarest options: Rattle with Berlin from their binaural direct-to-disc box set also cut by Emil Berliner (BPHR 160041). I did listen to the Rattle for this review but despite the excellent sound and playing, it seemed a bit of a safe and subdued rendition. The others I just didn’t have enough hours in the day to compare! There’s also a few highly regarded options I don’t own: like the Klemperer/Philharmonia on UK Columbia (SAX 2262) which I have been looking for for years, and would love to get my hands on. My point is: this is one of the most recorded pieces in the history of the vinyl record, you have plenty of options, so why consider this new reissue?

Are there other great versions I own? Sure, there’s Kubelik with Vienna on London Blueback (CS 6016), Solti’s complete cycle with Chicago also on London (CSA 2406), and Maazel with Cleveland again on London (CS 7007), Horenstein with the LSO on Quintessence (PMC 7028), the artistically excellent but sonically disappointing Walter with Columbia (MS 6389) and then of course there’s one of the rarest options: Rattle with Berlin from their binaural direct-to-disc box set also cut by Emil Berliner (BPHR 160041). I did listen to the Rattle for this review but despite the excellent sound and playing, it seemed a bit of a safe and subdued rendition. The others I just didn’t have enough hours in the day to compare! There’s also a few highly regarded options I don’t own: like the Klemperer/Philharmonia on UK Columbia (SAX 2262) which I have been looking for for years, and would love to get my hands on. My point is: this is one of the most recorded pieces in the history of the vinyl record, you have plenty of options, so why consider this new reissue?

Claudio Abbado is not someone I typically think of when hunting for interpretations of Brahms’ symphonic output, yet here with the Vienne Philharmonic the team summons up a rousing and convincing performance. Vienna at this point and time is a more well-oiled machine than in the 50s or 60s and it's apparent in the level of playing from soloists and the ensemble as a whole. Intonation is worlds better than the 1961 Karajan outing, and everything feels more assertive and confident. Abbado certainly has his detractors (a few notable classical reviewers consider him hopelessly overrated and over-recorded) but as a listener I couldn’t help but enjoy his direction here. There are some minor elements lacking: the first movement, especially in the beginning feels a little unsure of itself, and unfortunately you need that rock steady determination in the introduction to serve the material Brahms gives us. Also the fourth movement theme is not quite as expansive and grand as Karajan with Berlin, and there’s a bit less freedom in the slow movement. However there are also some magical moments in this recording, and once Abbado gets going he serves up some great energy along with his trademark micromanaging of solo musical lines (it works here) If this is your first time listening to this symphony, I think you are in for a nice treat.

The sound quality here is excellent, especially in the final movement. The mastering EBS has done to this recording helps it to excel over their previous effort with the Karajan box. Strings are more round, there’s more air around the instruments, and the big crescendos towards the tail end of the work sound far more open and relaxed than the rather tight and somewhat bright peaks on the Karajan/Berlin. There’s also a really nice sense of hall sound here, not so much in the timbre itself, but rather in the decay of notes and especially the resonance left over in the big orchestral “hits.” It sounds like what you would hear live in the audience, and I do tend to appreciate when recordings can capture that.

One minor gripe I have is that side one of my record was drilled/pressed slightly off-center, leading to some unwarranted intonation wobble in the delicate moments of the second movement ‘Andante.’ It really took me out of the “zone” because if I was hearing that from a live orchestra certainly some of the principal winds would be getting warning letters from management! I won’t knock the sound quality rating for that, because it’s very clearly a pressing issue from Optimal, but it’s very frustrating to encounter issues like this in classical pressings. None of my vintage LPs exhibit such pressing issues, and I wonder what quality control issues are happening in modern pressing plants to allow this (Classic Records had notorious issues with this a number of years ago with their classical pressings). When you pay $40 dollars for a modern audiophile reissue you shouldn’t expect defects that warp the sound of the recording they’re supposedly producing the most pristine version of.

I don’t expect the vast majority of buyers to encounter such an issue, so do I recommend this recording? Absolutely, especially if you don’t own this symphony already on record. It’s a finely played version in some of the best sound I’ve heard from Emil Berliner yet. It’s really the only in-print audiophile recording of this piece easily available right now, and if it does pique your interest in Brahms interpretations, you can also explore a plethora of other vintage versions.

Music: 9/11

Sound: 10/11

Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881-1945) was just as important in the development of 20th century symphonic music as Beethoven and Brahms were in their respective careers. Despite a long and distinguished career in Europe, by 1940 the composer was in dire straits. He fled Hungary to the United States that year to escape fascism, leaving behind many important connections and work as a conductor. Bartók was much less well known as a composer in the United States than he was in continental Europe. Coupled with an unfamiliarity with American culture, he felt like an outsider for the brief five years he spent in New York City. He survived mostly on a small research fellowship from Columbia University for his equally important work as an ethnomusicologist (Bartók in addition to his gift for composition, was an important and thorough researcher on European folk song traditions).

Moreover, Bartók’s health was failing him. Soon after his arrival in the US he started experiencing a slow and steady onslaught of symptoms that at one point was believed to be Tuberculosis. It was in fact Leukemia, for which the ailing composer wouldn’t receive a diagnosis until 1944.

Bela Bartók at the piano

Bela Bartók at the piano

Despite the bleak times, Bartók did have friends and champions in American musical circles. One of those friends was fellow Hungarian conductor Fritz Reiner, who was a longtime champion of the composer’s music and a personal friend. Reiner lobbied another esteemed conductor; Serge Koussevitzky, then music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, to commission a new orchestral work to be premiered by the orchestra. Koussevitzky and Boston premiered Bartok’s new Concerto For Orchestra on December 1st, 1944, just 10 months before the composer’s death. It was his last orchestral work, and has become by far his most popular.

Part of the reason for the success of the Concerto is the work’s accessibility, especially compared to the composer’s other major orchestral works which are far less melodic (his first two piano concertos are favorites of mine, but they will appeal to a much smaller audience than a work like this). So what are the musical ideas and motifs behind this twilight period work?

Bartók provided some program notes himself for the premier in Boston:

The general mood of the work represents, apart from the jesting second movement, a gradual transition from the sternness of the first movement and the lugubrious death-song of the third, to the life-assertion of the last one... The title of this symphony-like orchestral work is explained by its tendency to treat the single orchestral instruments in a concertant or soloistic manner. The ‘virtuoso’ treatment appears, for instance, in the fugato sections of the development of the first movement (brass instruments), or in the perpetuum mobile-like passage of the principal theme in the last movement (strings), and especially in the second movement, in which pairs of instruments consecutively appear with brilliant passages.

Bartók makes the clear distinction that this is a concerto for many different soloistic voices within the orchestra, although those solo voices often are found in doubles like in the 2nd movement Presentando le coppie, or in section tuttis. Despite its harmonic closeness to the orchestral tradition, many elements of the Concerto are steeped in the composer’s keen knowledge of Hungarian folk musical traditions, especially the use of unusual modes and inventive scale patterns. The use of these elements inside more traditions forms such as the Sonata form of the Finale.

The primary reference recording for this work has always been Fritz Reiner’s monumental 1956 reading with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on RCA "Living Stereo" (LSC-1934). It has been reissued by the audiophile labels many time but most recently (and excellently) by Analogue Productions with mastering by Ryan K. Smith at Sterling Sound. Reiner had a deep knowledge and appreciation of this piece, and despite the fact that Koussevitzky and Boston premiered the work, it always felt like Reiner really had ownership of it. However Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik’s 1974 recording with that same Boston Symphony has made an impression over time as well, even lauded over the Reiner iteration by some critics, so I thought it would be most prudent to compare the two, as they are both now in-print!

Overall, the Kubelik recording presented here is a punchy and clear rendition, with excellent soundstage and detail, and very thrilling dynamics. It does lack a little of the richness of the Analogue Productions Reiner recording, with less bloom in the low strings, and less warmth overall. I also felt a deeper and more present bass coming from the low brass and percussion on the AP. However, the AP does not have the level of pinpoint detail and clarity that this DG remastering possesses, and while the bass is not as uniformly deep or explosive as the AP, it is tighter and more refined, and there are a few select moments of really deep bass that will surprise those listeners with subwoofers. The fact that I am weighing the pros and cons of a 70s Deutsche Grammophon recording with an RCA "Living Stereo" recording reissued by Analogue Productions should tell you something though: that Emil Berliner has succeeded in making these records competitive with longstanding legacy audiophile favorites, and that’s a very good thing.

The playing on both renditions is convincing and excellent. The Reiner is more of a “straight ahead” reading, with power and energy, while Kubelik and Boston tend to spend more time in their phrases with a greater musical flexibility and tonal palate. Also, the individual solo voices on the Kubelik come across as more unique with greater expression. Honestly, both are superb in sound and performance, and I think they are different enough that they offer unique experiences. If I had to keep only one, sorry, but the Reiner is staying, it’s long been the go-to recording for so many fans of this work, but I’d still happily listen to this new "Original Source" pressing and not feel like I’m missing anything. The great thing about this hobby is we’re allowed to buy both, and that’s what I’d recommend here, because you get to hear the remarkable differences an interpretation can make to a piece.

Music: 10/11

Sound: 10/11

To sum it up: these releases genuinely impressed me, more so than did previous batches and certainly more than did the first few months of this series, which I think in hindsight can safely be described as early effort hit or miss. Thankfully there are no misses here. Each one of these records is spectacular and it makes the future of the extensive Deutsche Grammophon catalogue look very bright.

We add Mark Ward's YouTube videos covering the same releases

.png)