Big Lift for 10-year old Little Fwend

Lasse Gretland’s automatic tonearm lifter has found its way from Oslo onto turntables worldwide.

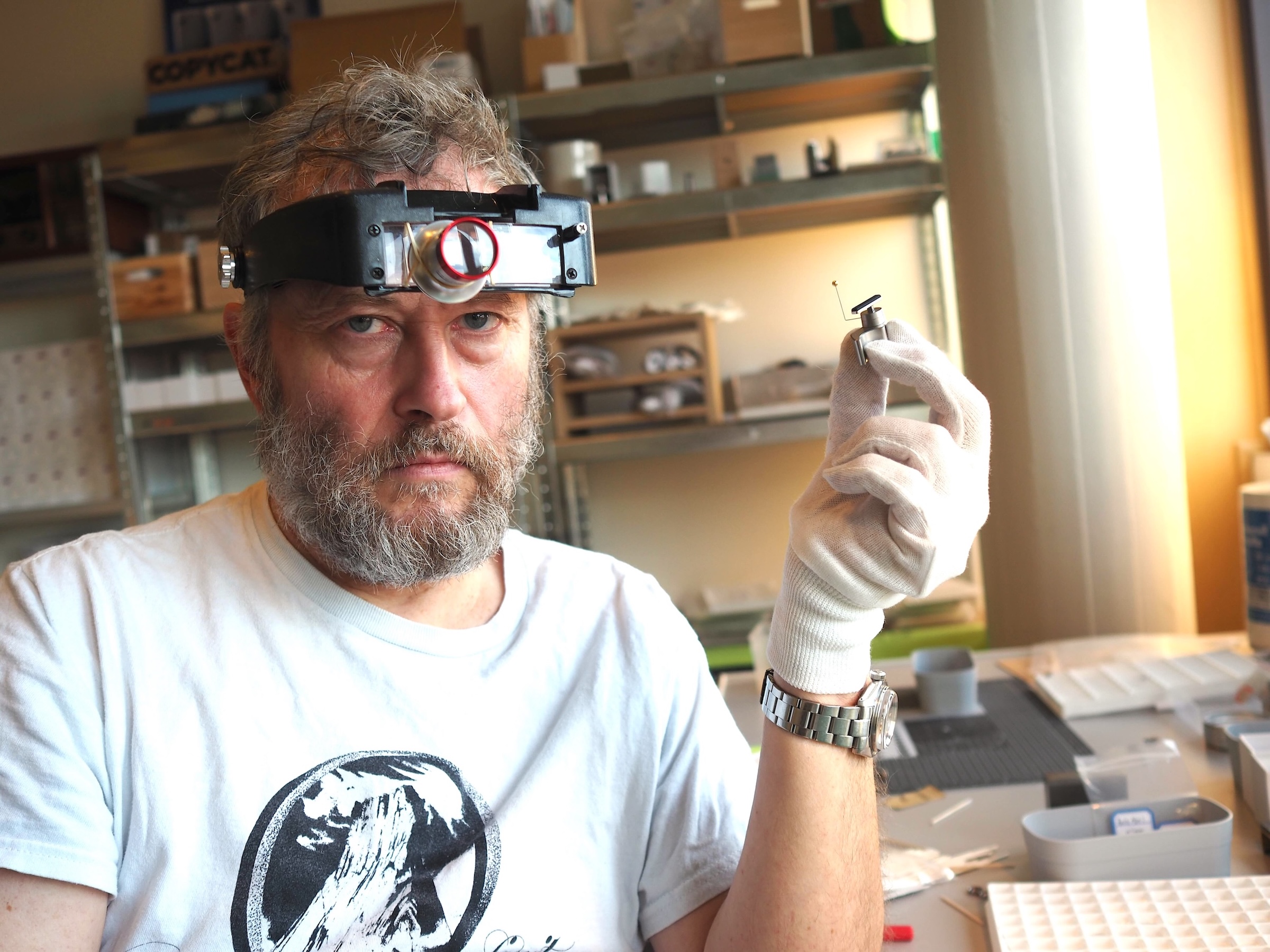

In a worn-down office space in a residential-industrial area in the northern part of Norway’s capital, Oslo, a man is hunched over a desk lit by a Richard Tapper table lamp. Meticulously piecing together tiny components of stainless steel into a small, serious-looking mechanical device, he’s wearing a pair of white cotton gloves, an obscure band T-shirt, faded jeans and Vans. The hair is roughly trimmed, the greying beard untamed, the look perhaps best described as «aging skater». A pair of custom-made magnifying glasses — cheap hardware from China, expensive optics from Switzerland, round out the ensemble. Meet Lasse Gretland (53), the iconclast behind Little Fwend, the automatic tonearm lifter.

A tonearm lifter, if you're not familiar, is what the name implies: a mechanical device designed to gently raise a turntable’s arm and cartridge from the record’s run-out groove once a side has finished playing. Introduced ten years ago this month, Little Fwend has, slowly but surely, taken a leading position in this very niche market.

For anyone indulging in vinyl playback, the steady thump of the cartridge riding the locked lead out groove at the end of a record is a timely reminder of life’s impermanence.

Not so with my first turntable, a very modest Garrard SP25 MKIII, inherited from my father when he upgraded to an ERA 444. As a side finished, the tonearm was automatically lifted and rather briskly returned to its resting place. That kind of robust electromechanical automation doesn’t mix well with the demands of ultra high resolution audio reproduction, however, and has virtually disappeared from today’s higher-quality turntables. Even most entry-level models are now fully manual, leaving the stylus tracking the inner groove until you lift the arm yourself. The result can be unnecessary wear on a fragile and often costly part. Opinions differ on whether excessive time spent in the runout groove can actually damage a cartridge over time — but who wants to take the chance (however much time the stylus spends in the runout groove is that much time shaved off the life of the stylus_ed.)?

The solution is as simple as it is ingenious. Little Fwend is positioned, according to the maker’s instructions, between tonearm and platter. The magnetic base and accompanying base plate makes fine tuning of placement easy. During playback, the arm passes just a few millimeters above the rubber pad that will later lift it. The mechanism triggers when the stylus moves into the record’s run-out groove and the arm touches a slender, sensitive piano-wire antenna. Because it’s so finely tuned, there’s virtually no stress on the cantilever or stylus when it activates. A fluid-damped cylinder inside the lifter rises under spring tension, lifting the arm those few crucial centimeters with a quiet, graceful motion that feels reassuring.

I recently visited the one-man operation behind said device. Lasse Gretland – by day a director at Oslo branding agency Notch – is friendly, fast-talking, energetic, and more than a little eccentric. He is a hi-fi obsessive, an analog purist and a DIY tinkerer with a soft spot for large american speakers, triode amps and vintage turntables from EMT, Garrard and Thorens. His network in the tightly knit audio community is large, and ever expanding. Full disclosure: The two of us have spent considerable time together, listening to records and discussing audio, even dj-ing with our club concept, No Club for Old Men.

The Little Fwend idea was born out of frustration, Lasse tells me. For years, he had wondered why no one was making a proper tonearm lifter, like the Audio-Technicas and Ortofons of old.

The Little Fwend idea was born out of frustration, Lasse tells me. For years, he had wondered why no one was making a proper tonearm lifter, like the Audio-Technicas and Ortofons of old.

“I won an auction on eBay and bought an old Audio-Technica AT-6006 Safety Raiser for 260 dollars. But it felt a bit too plasticky, and it was held in place with double-sided tape. I thought: why isn’t there an Aston Martin of tonearm lifters — something elegant and mechanically solid?”

Together with industrial designer Marius Sundsåsen, Lasse began developing his own, partly through reverse engineering the Audio-Technica. (Audio-Technica seems to have repaid the compliment with their relaunched Safety Raiser, featuring the in-body release mechanism placement pioneered by Little Fwend).

Little Fwend mounted on a Garrard 401 in an Audio Grail plinth. Photo: Audio Grail

Little Fwend mounted on a Garrard 401 in an Audio Grail plinth. Photo: Audio Grail

The first product was launched in 2015, not without drama. When Lasse set up a small table for his first showing at the New York Audio Show that November, with a turntable, a radio serving as amplifier, and a prototype that didn’t work, he was close to tears.

”The parts had arrived from Denmark just the night before. Late, of course. And the thing didn’t work. But Dita (Lasse’s wife, who does all of Little Fwend’s digital brand communication) told me to relax, pulled out her nail file and said, ‘Why don’t you just do this?’ Suddenly, it worked! Pretty great. And that same day, I met Art Dudley.”

Lasse had set up the Little Fwend on his Thorens TD124 with a 12-inch Thomas Schick arm and an Ortofon SPU cartridge, hooked up to a Tandberg portable radio. One of the first to notice and stop by the very modest stand was Dudley — the legendary Stereophile writer we sadly lost in 2020. He had the same turntable and arm at home, and was curious about the little gadget.

“We ended up chatting for half an hour. Art was incredibly kind, and he wanted to review it. The rest, as they say, is history.”

Dudley’s glowing review appeared in 2017. Tracking Angles’s editor concurred at his previous gig in 2018. Despite the positive reviews, production remained small. But when the pandemic hit, and distribution channels collapsed, something unexpected happened: business took off.

“People were sitting at home listening to records,” he says. “We sold 30 percent more in 2020 than the year before.”

The storage room at Lasse’s combined office, workshop and warehouse is filled to the brim with vintage audio gear. The stuff gathered here would make enthusiasts hum softly with delight: assorted horn speakers, tube amps, turntables, cartridges, boxes of tubes, cables, soldering irons, spare parts. Some pieces are gathering dust, others are mid-restoration. A pair of EMT 930s radiate authority over in the corner. The collection currently holds 27 turntables, a bunch of tonearms and assorted step-up transformers. On the side of his side business, Lasse now rents out curated audio system to bars and clubs, to bring cash into his Little Fwend operation. He also distributes the excellent «Monster Can» MC step-up transformers from Michael Ulbrich’s Consolidated Audio of Berlin. His hifideli.com website is another project: some kind of weird encyclopedia/rabbit hole for analog obsessives, still very much under construction.

The storage room at Lasse’s combined office, workshop and warehouse is filled to the brim with vintage audio gear. The stuff gathered here would make enthusiasts hum softly with delight: assorted horn speakers, tube amps, turntables, cartridges, boxes of tubes, cables, soldering irons, spare parts. Some pieces are gathering dust, others are mid-restoration. A pair of EMT 930s radiate authority over in the corner. The collection currently holds 27 turntables, a bunch of tonearms and assorted step-up transformers. On the side of his side business, Lasse now rents out curated audio system to bars and clubs, to bring cash into his Little Fwend operation. He also distributes the excellent «Monster Can» MC step-up transformers from Michael Ulbrich’s Consolidated Audio of Berlin. His hifideli.com website is another project: some kind of weird encyclopedia/rabbit hole for analog obsessives, still very much under construction.

Assembly of the Little Fwend happens in the «clean room» (relatively speaking) next door. A workbench is covered with lifters in various stages of completion, evidence that the high energy motormouth in charge of operations also has a more zen-like operational mode. After years of sourcing nickel-plated brass parts from Denmark, Lasse recently moved parts production to Switzerland, in collaboration with renowned mechanical engineer Micha Huber — the man behind Thales turntables and contributions to several EMT designs.

“Using nickel-plated brass wasn’t our smartest decision,” he says. “Marius had to rework the friction surfaces to meet our tolerance specs for smooth operation. He’s an industrial designer, but also a self-taught watchmaker, with vintage Swiss lathes and the skills to do precision work like that. But when demand surged around 2022–23, and Marius was spending 20–25 minutes finishing and assembling each Fwend, I had to do something. Late in 2024 I hired Micha as consulting engineer, and we made some design tweaks to cut assembly time. He suggested switching to uncoated stainless steel, eliminating the need for all that post-processing. The new parts are stunning — though working with the Swiss is a nightmare. Everything must be documented, every 1/100th millimeter change officially approved. But the results are the best we’ve ever had.”

The new components cost about 40 percent more to produce, but Gretland has kept prices nearly the same. That might change.

The new components cost about 40 percent more to produce, but Gretland has kept prices nearly the same. That might change.

“We’ve never raised prices. But people are used to paying for premium products now. When the quality goes up, the market can handle it.”

Little Fwend comes in three versions, designed for different tonearm heights — Low, High, and Disco (for the Technics SL-1200). The high model might eventually be phased out, replaced by a magnetic extension to the low version. The upcoming Low Mk2 and Disco Mk3 will sell for 229 and 219 euros respectively. the High remaining in stock for 239 euros. US prices for the new models are still to be finalized, pending the outcome of the tariff.

The U.S. is by far the biggest market, with Fwends sold in increasing numbers through retailers like Music Direct, Turntable Lab, SkyFi and Audio Advisor.

“We don’t have a web shop anymore — too much paperwork. Everything goes through distributors. Mofi Distribution handles the U.S., and they’re fantastic,” Gretland says.

He estimates about 1,100 units sold last year — roughly double the figures from the early years.

“We’ve got almost 500 customers on the waiting list without even advertising. That’s pretty wild for a product this niche.”

The real breakthrough came when Technics — the Japanese brand behind the legendary SL-1200 DJ model – started showing interest.

“When they relaunched the SL-1200 series in a high-end version, people suddenly started noticing our little lifter. I met some folks from Technics’ Osaka office, and they became fans. It’s a huge corporation, so they can’t say anything official, but we got a sort of unofficial seal of approval.”

Earlier this year, Little Fwend collaborated with Technics Germany. The result: the Disco Fwend sold out in weeks.

Earlier this year, Little Fwend collaborated with Technics Germany. The result: the Disco Fwend sold out in weeks.

“After that, everything took off. We reached a new audience — not the hi-fi freaks, but the lifestyle music lover crowd. The volume there is much bigger, and it has lifted the other models, too.” The Low model was consequently sold out in July.

It should in all fairness be mentioned that Little Fwend isn’t alone in the market. Turntable maker Pro-Ject has a simpler plastic device called the Q-Up, and then there is the reissued Audio-Technica mentioned above.

After a decade of part-time effort, Little Fwend celebrates its 10th anniversary this month. There are plans for the next phase, including small, handmade limited editions tailored to specific turntable models, like the one already offered for Rega’s P8/P10. Don’t be surprised if a similar solution appears for his own vintage EMT 930s.

“People love it when we make something bespoke for their player. It’s emotional — it builds loyalty,” he says.

Turntable brands have floated ideas for collaborations, but Lasse is wary.

“We’ve had offers to make a version that ships with turntables from the factory, but I don’t want that. Little Fwend is its own brand. It’s not going to become some anonymous OEM part.”

Time to address the elephant in the room: is it really that harmful to let the stylus sit there in the run-out groove?

Gretland, unsurprisingly, thinks so:

“There’s probably no more friction between stylus and vinyl in the run-out groove than elsewhere, but all play causes wear. The diamond tip lasts maybe 1000–2000 hours before it needs re-tipping. That’s expensive and time-consuming, so why wear it unnecessarily? Then there are two other issues: First, on many records, the inner transition groove isn’t perfectly parallel. You hear a tiny pop — like a nick in the vinyl. Not great for the cantilever or the rubber damper to hit that edge every 1.8 seconds at 33⅓ RPM. Second, the stylus sits at a tracking angle that’s a bit off 90 degrees in the inner groove — meaning asymmetrical wear over time. That can affect tracking and frequency response.”

He pauses, then smiles:

“Little Fwend doesn’t do fear-based marketing, but here’s a worst-case story. I came back from a swim at the summer cabin once, and found the stylus sitting halfway across the paper label. That’s never a good sign for the diamond’s future. Dust must have built up and packed under the stylus at the inner groove transition. Lose friction there, and if antiskating isn’t set perfectly, the stylus slides inwards. Luckily, it was just a cheap Shure V15 MM cartridge, not the Lyra Kleos at home.”

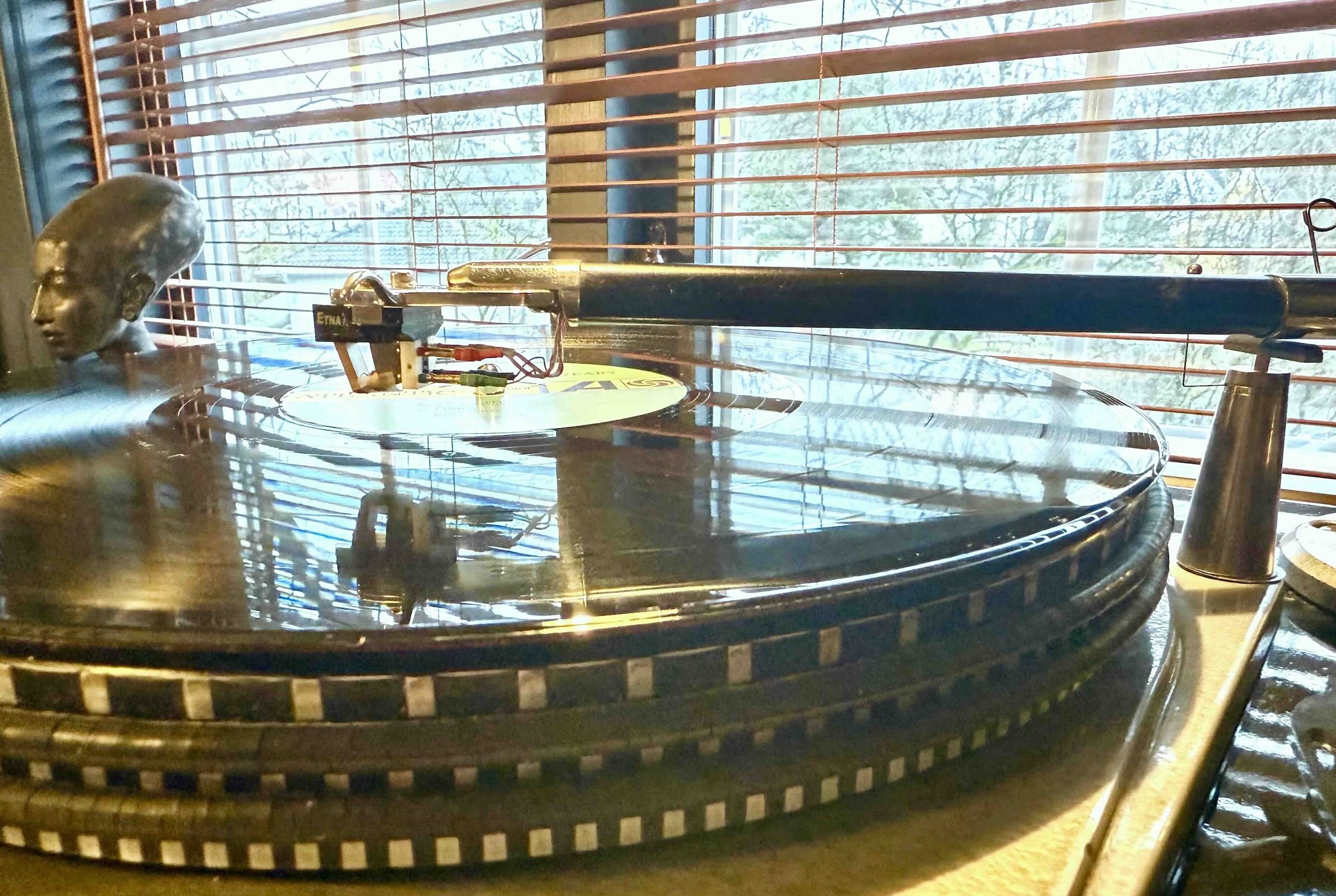

The author's Little Fwend has just lifted the arm from the 2023 reissue of Max Roach's «Members, Don't Git Weary».

The author's Little Fwend has just lifted the arm from the 2023 reissue of Max Roach's «Members, Don't Git Weary».

For a second opinion. I reached out to J.R. Boisclair, managing director of WAM Engineering, makers of the WallyTools setup kits for precision turntable adjustment. He replies via email:

“In the case of the lockout groove, the same spot is being revisited by a warm stylus once every 1.8 seconds (@ 33.3 rpm). Hypothetically, this would significantly increase the risk for wear in the lockout groove and an eventual transference of what may be very difficult to remove material from your stylus/cantilever assembly. Watch out in particular if you are rotating at 45rpm. It will potentially cause damage more efficiently not because of an increase in coefficient of friction (there isn't any CoE increase to be significant enough between 33 and 45) but because of the higher frequency with which the stylus will revisit the same location on the groove. Also, the epoxy which holds the stylus to the cantilever can take a real beating if kept heated for too long. I would expect its life to be shortened if kept heated for a long duration”.

So says Mr. Boisclair, seamlessly segueing into a product pitch:.

– You might also consider the benefit of an automatic lifter is even higher if you do not use a WallySkater to manage your horizontal forces in your arm because the effective moment arm at the ~50mm lockout groove radius (which, in conjunction with friction, is THE cause of skating force) is VERY high and you can expect with enough time you will deform your cartridge suspension permanently. Lasse is a smart cookie indeed. I'd say he is onto something!

At his workbench, Lasse dons his magnifying glasses and gets to work on another Fwend.

– When I stood there in New York, with my wife’s nail file and an unfinished prototype, I had no idea this would become my life's project. But look at me now!

.png)