Britten’s WAR REQUIEM Revisited - A Masterpiece Newly Relevant - PART 2: Making a Legendary Recording

Decca's 60th Anniversary Restoration and Remastering of one of the catalogue's greatest achievements prompts a re-examination of this profound anti-War statement

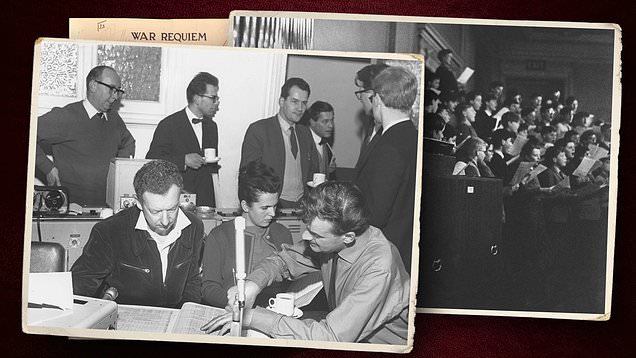

Rehearsing the War Requiem in Coventry Cathedral, 1962. Soprano soloist Heather Harper is at far left, tenor soloist Peter Pears is at far right. Main conductor Meredith Davies (center left) confers with chamber orchestra conductor Benjamin Britten (center right)

Rehearsing the War Requiem in Coventry Cathedral, 1962. Soprano soloist Heather Harper is at far left, tenor soloist Peter Pears is at far right. Main conductor Meredith Davies (center left) confers with chamber orchestra conductor Benjamin Britten (center right)

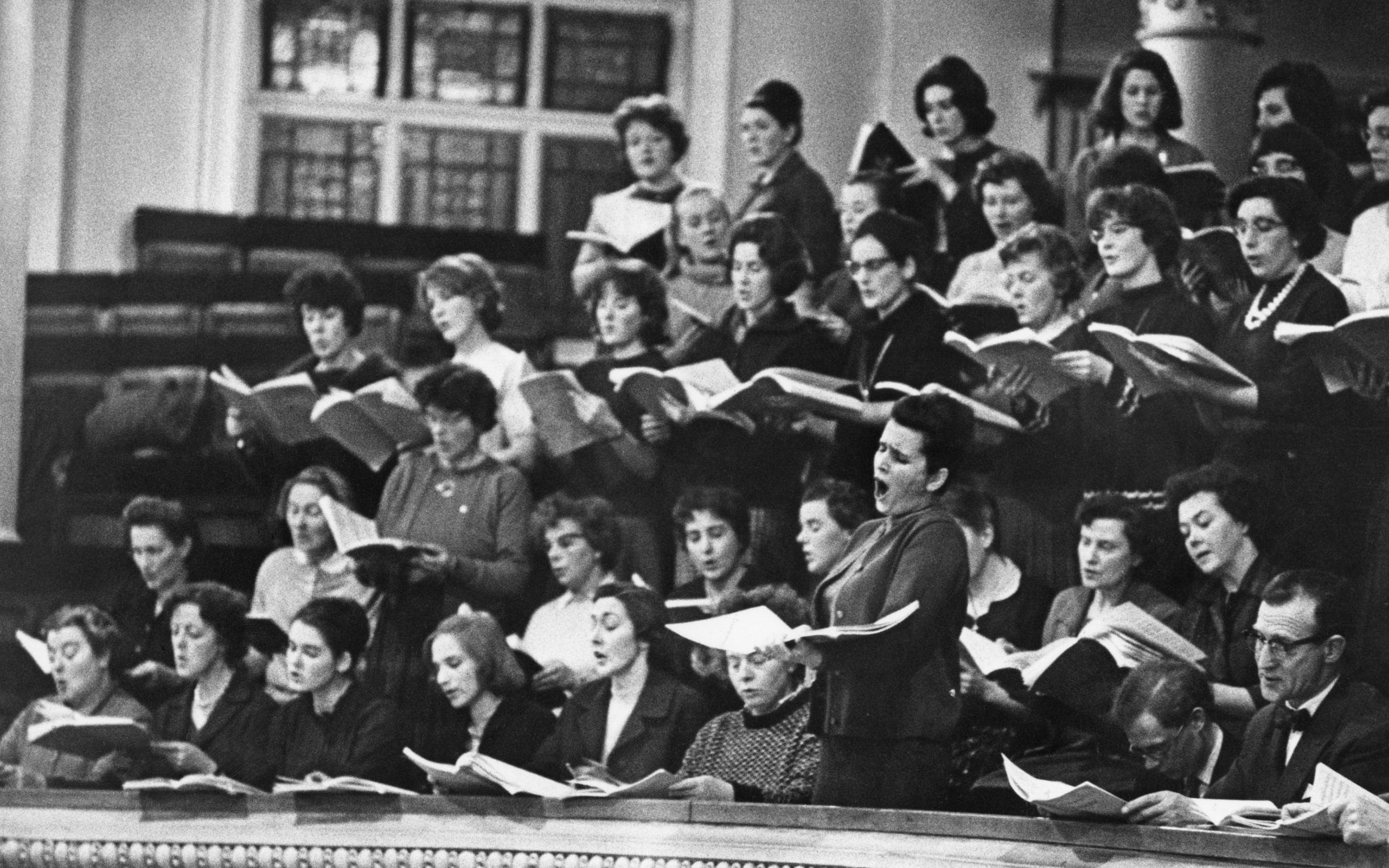

By all accounts, the first performance of the War Requiem in Coventry Cathedral, while understandably powerful, was a bit of a hit-and-miss affair, nearly derailing completely several times. Hardly surprising, since this is a huge, complicated work both logistically and aesthetically, and it was dogged by a number of setbacks even before the performance began.

Britten’s original intention had been for the soloists to be drawn from three of the countries at the heart of the two world wars, to express a sense of reconciliation: from England, tenor Peter Pears; from Germany, baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; from Russia, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya (wife of ‘cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, dedicatee of several Britten works). However, at the last moment the Soviet authorities would not allow Vishnevskaya to attend, so her understudy, the British soprano Heather Harper, stepped in. (Vishnevskaya was later allowed to come to Britain to record the work).

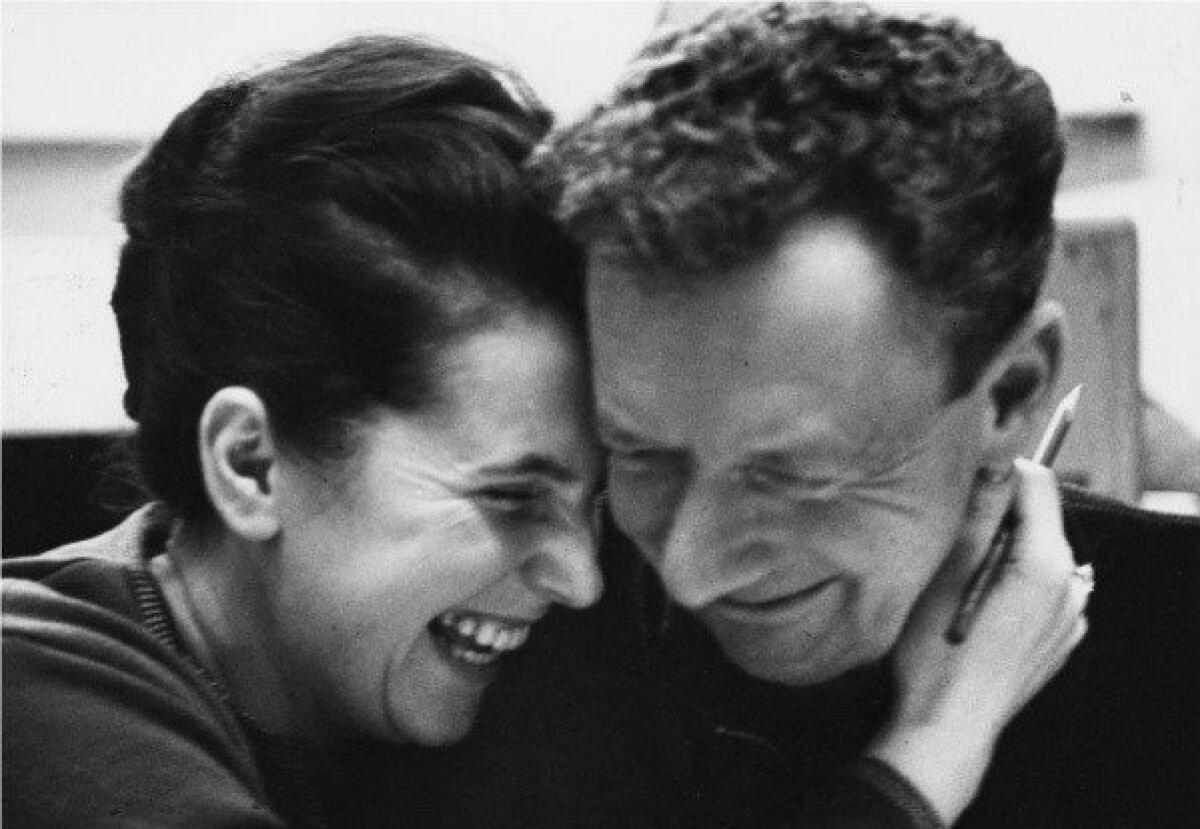

Peter Pears (l.) rehearsing the War Requiem at Coventry Cathedral, 1962. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is seated behind him, to the right

Peter Pears (l.) rehearsing the War Requiem at Coventry Cathedral, 1962. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is seated behind him, to the right

John Culshaw, Decca’s brilliant producer, responsible for legions of legendary classical recordings, including the watershed recording of Wagner’s complete Ring cycle under Georg Solti, and most of Britten’s catalogue on the label, has covered his history with the War Requiem in his essential, and eminently readable, autobiography Setting the Record Straight.

For those of you not in possession of this book, there are extensive extracts from his first-hand account included with the beautiful booklet in the new deluxe reissues under consideration here. He talks about the lead-up to that first performance, the various trials and tribulations that unfolded.

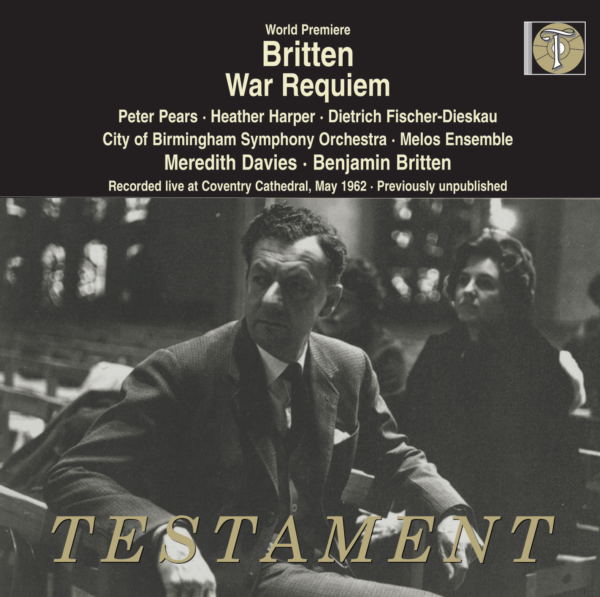

A broadcast recording of that first performance is available on Testament, and for the Britten completist it is worth seeking out, warts and all.

There had been extensive discussion of Decca - Britten’s record company - doing a live recording of that first performance, but numerous logistical concerns ended up precluding that possibility. Culshaw himself was not in favor, and he is deliciously candid about the back-room conversations and strategies that finally led up to Decca green-lighting a dedicated studio recording. Culshaw had already worked closely with Britten on a number of outstanding recordings (including Peter Grimes), and had earned the composer’s trust - not something Britten bestowed lightly. In one of the most touching passages in his book, Culshaw recalls spending a day with the composer when he was in the midst of composition, uncharacteristically sharing what he had written so far:

‘It was much more than a piece for the occasion of Coventry, no matter how important that might be; and the use of the poems by Wilfred Owen, far from being an anachronism, brought the personal inhumanity of war into focus. A bomb from an aircraft is an anonymous weapon dropped by an anonymous foe; but the soldiers in the War Requiem, although they do not know each other, are human beings, each facing the requirement of his own or the other’s death. The War Requiem has therefore no specific relevance to any particular war; it relates to war in general and to its essence, which is death.’

John Culshaw and Benjamin Britten discussing the War Requiem score (from the booklet included with War Requiem reissue; photo from the Tully Potter collection)

Britten was perhaps unique amongst composers of his time (or any other) in the extent to which a majority of his music was represented on easily available commercial recordings from one of the main record companies, Decca, often within a few short years of its first performances. It’s a deep and abiding catalogue. Beyond his own work, his recorded legacy as a performer of other composers’ music (both as conductor and pianist) is also extensive - and a beacon of excellence in terms of both performance and recorded sound. In short, if a Decca record has Britten performing on it, it will sound terrific and is eminently collectable. It might therefore surprise you that the composer had very ambiguous feelings about the whole recording process, the record culture in general, and was only coaxed into conducting anything at all very reluctantly over many years by Culshaw. (He suffered from debilitating stage nerves). Some of this is gone into in relation to the recording of the War Requiem.

Culshaw:

'… I went to Aldeburgh to spend some days with Britten discussing the best approach to recording the War Requiem. Quite apart from his natural reticence as a performer he had genuine reservations about what I would call recording values, which he eventually spelt out, and which caused much misunderstanding, during a speech he gave in Aspen, Colorado. His basic concern was with the attitude that any recording can be regarded as sacrosanct. (He said the same, of course, about any live performance). Music to him was a living and therefore a changing art; musical notation was notoriously inexact, and nothing - not even a composer’s performance of his own music - represented the last word. What he deplored was the attitude of some record enthusiasts, who could not be torn from their devotion to a particular interpretation, and who by definition closed their ears to any that departed from the familiar norm. That much said, he had more enthusiasm than any other artist I knew (apart, perhaps, from Karajan in those days) for making the utmost use of whatever special facilities recording could offer - which in the case of the Requiem, concerned the many different perspectives required in an accurate performance of the score. Sometimes these can be achieved in public performance: the sound of the boys’ choir floating from the top gallery of the Royal Albert Hall can be magical, and in a cathedral the main chorus can build to a sort of sound intensity of the kind required by Berlioz and Verdi. But the chamber group and the male soloists in Britten’s Requiem tend to get lost in such vast surroundings, and their words are important. So in planning the Requiem recording we wanted to avoid any such compromise.’

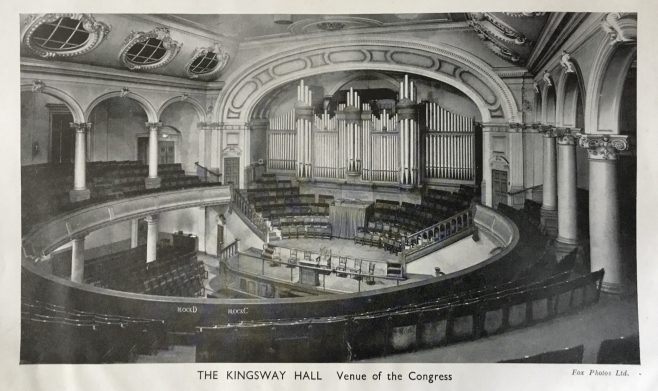

The chief engineer for the sessions would be the legendary Kenneth Wilkinson, familiar to Tracking Angle readers as the force behind many of our favorite classical recordings, including the incomparable Royal Ballet Gala Performances box set on RCA Living Stereo, conducted by Ernest Ansermet. Like that set, the War Requiem was recorded in one London’s most acoustically perfect spaces, Kingsway Hall.

Culshaw:

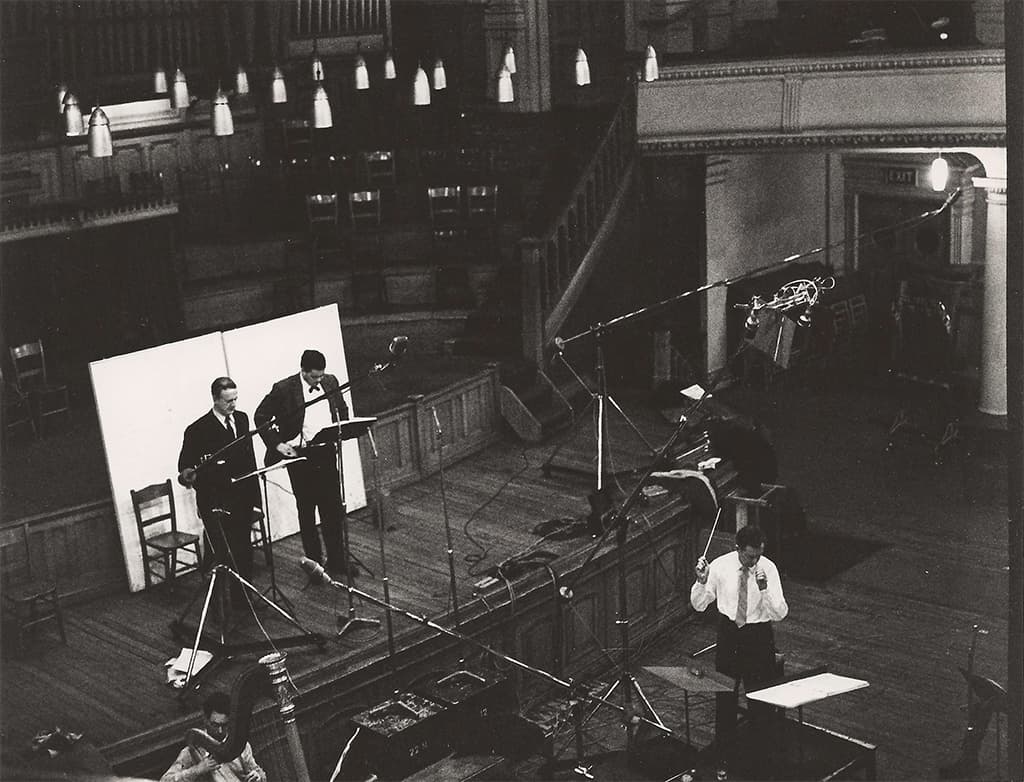

‘The natural acoustic of Kingsway Hall was ideal for the full orchestra, the main mixed chorus and the soprano soloist. The orchestra was to be placed as usual on the floor of the hall; the main chorus and the soprano would be located in the main part of the balcony with their own microphones, for they are concerned only with the liturgical (and therefore principal) part of the work...

Galina Vishnevskaya with the Main Chorus (Photo by Decca)

Galina Vishnevskaya with the Main Chorus (Photo by Decca)

'The boys’ chorus, which is required to be in yet another perspective, would also be in a corner of the balcony, but without extra microphones...

Simon Preston (organist) with the Highgate School Choir (Photo by Decca)

Simon Preston (organist) with the Highgate School Choir (Photo by Decca)

'... and the instrumental ensemble with the two male soloists - who represent the British and German soldiers, and sing in English throughout - would be on the “stage” in front of the orchestra but behind the conductor.

Peter Pears (l.) with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (c.) and Benjamin Britten (r.) (Photo by Decca)

Peter Pears (l.) with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (c.) and Benjamin Britten (r.) (Photo by Decca)

'... We hoped in this way to achieve both the clarity and the overall sonority required in different parts of the work. Because of the complexities it is usual to have two conductors for the Requiem - one to handle all the main forces and the other to look after the ensemble and the male soloists (some of the overlaps can be extremely tricky, and were among the things that went wrong during the premiere). But after some persuasion Britten agreed that in recording conditions he could handle all the forces himself, although he usually conducted the smaller group.’

Aficionados of the many great classical recordings made in Kingsway Hall will be delighted by the inside look offered by Culshaw’s descriptions of the venue’s less attractive qualities, in connection with his detailed account of soprano soloist Galina Vishnevskaya’s fit of the vapours when she first turned up at the sessions:

‘It struck me later that even Kingsway Hall itself may have dismayed her. The rest of us were so used to its general shoddiness that we scarcely noticed that after several hours in the hall one was covered with a thin film of grime which rose from coke-burners in the basement. EMI and Decca paid the Methodist authorities both a substantial retainer and a daily fee to use their church as a recording hall, in return for which the Rev. Donald Soper (later Lord Soper) provided nothing but the hall itself and a vast list of restrictions. Yet despite the absurdity of its design, its innate hideousness and the fact that underground trains rumbled to and fro directly beneath the hall (the sound they made had to be “sucked out” of the low bass frequencies when tapes were dubbed for disc) nothing altered the fact that it had the finest recording acoustic in London.’

Galina Vishnevskaya with Benjamin Britten

Galina Vishnevskaya with Benjamin Britten

Knowing that Britten’s 50th birthday would fall some months after the sessions, Culshaw arranged for the rehearsals to be secretly recorded. Nearly 16 hours of closely guarded material was then edited down to a handy 50 minutes or so, then pressed onto a single record that Culshaw presented to the composer on his birthday. Engineer John Mordler had recently joined Decca, and he was given the task of surreptitiously recording and editing the rehearsals, aided by Peter van Biene who was sitting in a concealed control room. Mordler recalls: “I recorded the voice of Ben Britten with two mikes, one on the conductor’s stand and one in the control room, but I was out of sight, hidden in the mono recording room situated up the stairs at the side of the stage.”

That extra rehearsal record/CD/SACD is included in both reissue packages, and it offers a wonderful insight into Britten’s process. In the accompanying booklet, the composer’s thank you note to Culshaw is reprinted, and when I saw it I had a real moment of recognition.

Why? Because Britten’s handwritten note is on exactly the same notepaper on which he once wrote to me, aged around 15, in reply to a letter I had sent to him. I had attended a recital by Peter Pears and Osian Ellis, and, talking to Pears after the concert, I had expressed my own enthusiasm for Britten’s music (which I had first discovered when singing one of his choral works, aged about 10). Pears had suggested I write to Britten (who at that time was far from well - he would die from heart failure only a short year later, in 1976). I still treasure Britten’s friendly letter in return, on that very same notepaper.

(Another personal sidebar here. A few years later, in 1979, I was working at the Aldburgh Festival as a Hesse Student. We would help run the festival in return for going to all the concerts free of charge. I once served lunch to the great Russian ‘cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who ate - mostly with his fingers - and spoke with his companions as effusively as he played the ‘cello. Anyway, the superb - and then young - pianist Murray Perahia gave a spellbinding concert of Mozart piano concertos, conducted from the keyboard. It felt like the music was coming directly from Mozart himself through the musicians. During the intermission I strolled into the car park and there, seated in his car, was Peter Pears. Tears streamed down his face. It must have all reminded him too vividly of the companion he had so recently lost, whose greatest love in music was Mozart).

Returning to the main narrative…

We learn more about the technological details of the sessions in Reissue Producer Dominic Fyfe’s excellent booklet essay. He was able to speak to three surviving engineers from those sessions (including Mordler).

Fyfe:

‘Pete (van Biene) was another 1962 Decca recruit and he, along with Wilkie’s (Wilkinson’s) assistant engineer Michael Mailes, have enabled us to dig deeper into how the original recording was made. Just 17 microphones were used (around half the number that would most probably be used today) and, remarkably, the sound was mixed straight to stereo. This was standard practice for Decca recordings in that era and a characteristic that distinguishes the “Decca Sound” from its rivals. The balance was perfected on session but, as John Culshaw’s reminiscences reveal, the recording set-up was the result of months of painstaking planning with Britten. This was especially relevant for a work which required multiple perspective and planes of sound. Mike Mailes recalls how the ethereal effect around the boys’ choir was achieved by placing a microphone in the stairwell leading to the balcony in Kingsway Hall. Listening to the Offertorium, for example, we can hear how the effect of an otherworldly acoustic is realised perfectly. It is all the more remarkable for being entirely natural. Wilkie’s diagram of microphone placement (reproduced on page 9 of the booklet) reveals “X56 ECHO” positioned at the back of the balcony: this was the Neumann KM 56 in the stairwell….

Kenneth Wilkinson's "Electrical Record of Session" as reproduced in the booklet accompanying Decca's reissue of the War Requiem (from the Decca Archives)

‘Two types of microphone were used at the War Requiem sessions: omnidirectional Neumann M 50s and cardioid KM 56s. Wilkie had long favoured the omni M 50s and deployed three of them - left/centre/right - on the classic Decca “tree”, and a further two as left- and right-hand outriggers. Session photographs (extensively reproduced in the booklet) reveal a baffle placed between the left and right mics on the tree itself. Even as late as 1963 Decca engineers were still experimenting with the best configuration for the tree. In Vienna, Gordon Parry was using the highly directional KM 56s on his tree for the Ring, giving a powerfully visceral sound of pinpoint precision. Wilkie, meanwhile, was looking to marry the extended low frequency warmth of the M 50 with the directionality at high frequencies characteristic of the KM 56. The baffle was thought to provide greater high-frequency definition for the M 50s and thus a greater stereo effect, even if using it resulted in some colouration of the sound. Originally, one further M 50 was used to capture the Melos Ensemble, placed to the right of Britten, but Pete van Biene recalls this being replaced with an M 49 switched to cardioid to achieve a closer, drier perspective. The remaining microphones for the soloists, chorus, percussion, piano and horns were all KM 56s.’

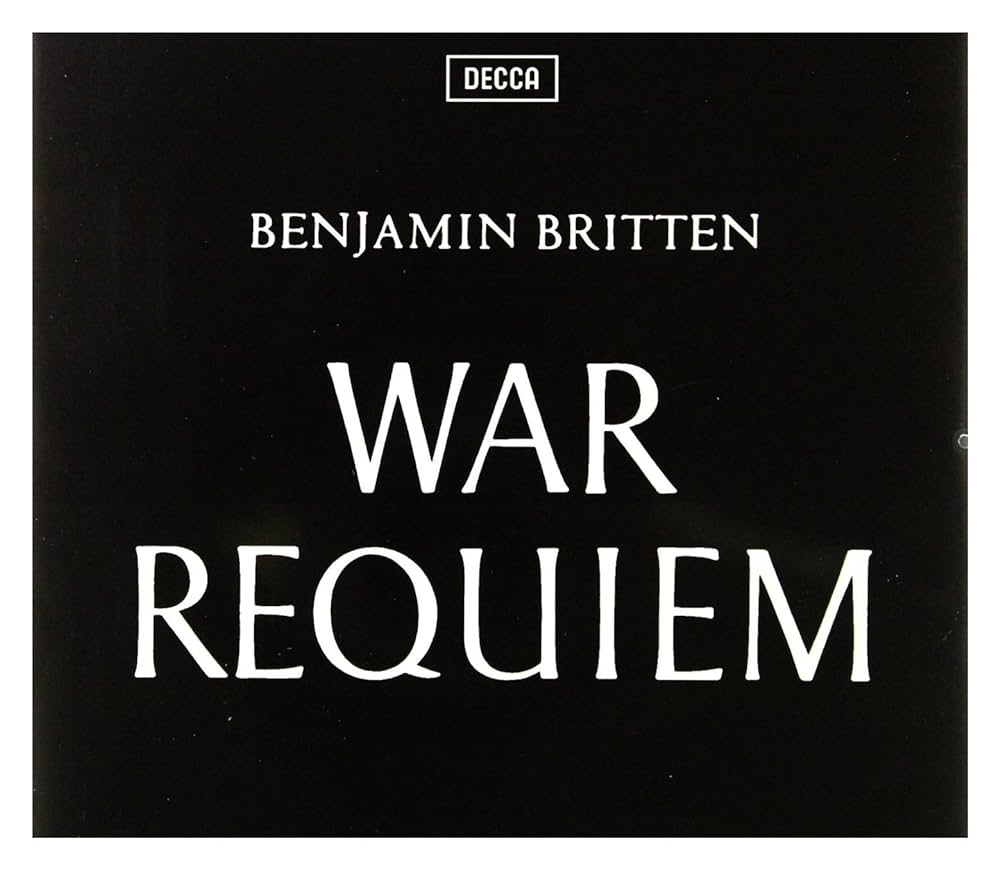

Culshaw’s account of the making of this landmark recording goes into some detail about the striking design of the LP box itself, and thankfully so.

It is simply one of the boldest and most memorable LP designs ever created. I remember as a kid that if you went into the home of any classical music lover with a record collection you would see two things: one would be the Solti Ring cycle - either one or more of those four box sets with their vivid artwork - and the Britten War Requiem, a complete contrast visually. The box cover was simply a solid gloss black, with four words printed in white: Benjamin Britten - War Requiem.

It’s an incredibly bold, modernist visual statement for a classical record in 1963, and Culshaw talks about all the resistance from his art department (who had churned out all manner of traditional, pictorial covers that he rejected) and the label bosses to this design, derived from the cover of the printed score published by Boosey & Hawkes.

But once you see it, you cannot imagine anything else being more appropriate. And I am positive that when the great art director for Factory Records, Peter Saville, came to create designs for his covers of Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures and New Order’s Substance, that cover for War Requiem nudged him in the direction he eventually took - whether consciously or not.

Cover art for Unknown Pleasures

Cover art for Unknown Pleasures

Cover art for Substance

Cover art for Substance

When the Decca recording of the War Requiem was released it was immediately anointed as a classic recording of what had already been instantly hailed as a masterpiece. “Masterpiece” is a much overused word, but the War Requiem has worn its reputation justly, and, alas, bites more keenly today than it ever did. How dismayed at that would its pacifist composer be.

That Culshaw, Wilkinson and the Decca team were able to represent in sound the many acoustical layers and perspectives of this work so flawlessly is remarkable - and unique. Yes, there have been other fine recordings of the War Requiem since, but none of them so completely nails the unique sound world of this piece. Performance-wise, Britten and his forces also remain the definitive benchmark. Indeed, any live performance of this work, let alone recording, has much to live up to: once you know these records as well as I and many others do, it’s hard not to find other renderings wanting. Another fact that Britten - the eternal sceptic of record collecting culture and the very notion of a “definitive” recording - would have been dismayed by.

Culshaw’s account of the making of this timeless recording concludes with this delicious anecdote which proves, yet again, that the myopia and, frankly, stupidity of many who work in the record industry has a long and noble tradition. Decca was wrong-footed by the instant commercial success of the box set, failed to press even close to enough copies, and then took far too long to make up the difference.

Culshaw:

‘… In the end it was more than two months after the announced release dates that the initial orders could be fulfilled, and although the Requiem became an undisputed best-seller there was no doubt at all that it would have sold even more had it been readily available when the public demand was at its height. When I challenged the gentleman responsible his response was bland. “Daren’t take the risk, old boy. First thing of Britten’s that’s ever sold at all”. He then came out with a line that haunted me for the rest of my career. “Do you think you could talk him into writing another Requiem that would sell as well? We wouldn’t make the same mistake twice.”’

Control Room during the Recording Sessions for the War Requiem. Engineer Kenneth Wilkinson can be seen at top left. Seated at console are Britten (l.), Vishnevskaya (c.) and John Culshaw (r.) (Photo by Decca)

Control Room during the Recording Sessions for the War Requiem. Engineer Kenneth Wilkinson can be seen at top left. Seated at console are Britten (l.), Vishnevskaya (c.) and John Culshaw (r.) (Photo by Decca)

Coming up in Part 3, a detailed discussion of the restoration of the original master tapes of the War Requiem recording, and an assessment of the sound of the new vinyl and CD/SACD reissues in relation to the original Decca vinyl pressing.

And you can read Part 1 of this trilogy of articles, describing the genesis and composition of the War Requiem, here.

.png)