Classic A Cappella: The King's Singers' "Contemporary Collection"

Records "Off The Beaten Track"

Long before the vocal stylings of the Barden Bellas and Barden Treblemakers of the Pitch Perfect movies, the crown for virtuosic a cappella singing rested firmly on the head of the King’s Singers, a 6-man vocal ensemble that has been around in different incarnations for over 50 years.

The group was formed in 1968 by a group of choral scholars who sang in the world-renowned choir of King’s College Choir, Cambridge - home to the beloved annual Christmas Eve Festival of Lesson and Carols broadcast on radio and television to an audience of millions around the globe. The King’s Singers quickly found enormous critical and commercial success, performing a huge range of music from the serious madrigal and other vocal repertoire of the Renaissance to special arrangements of standards, pop, and novelty songs. At the height of their popularity in the 1970s and 80s, the King’s Singers were everywhere, even appearing regularly on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Comprising two counter-tenors, one tenor, two baritones, and one bass, the King’s Singers reveled in their virtuosity (always performing without music scores), reinventing the sound of the typical unaccompanied vocal ensemble. Recording regularly for their first record label EMI, they were part of a wave of successful vocal groups that included the Swingle Singers (later renamed the Swingles) and the Manhattan Transfer. But what set the King’s Singers apart was the incredibly wide range of repertoire they presented.

And nowhere was this more on show than the :”off-the-beaten-track” record under consideration here, a 1975 collection of new works all commissioned by the group. This album, like many other King’s Singers records from this time, has never been issued on CD, but it is absolutely one of the best in the group’s entire catalogue - distinguished by the wide range of musical styles explored in these works and by the brilliance of the performances. If I had only one record by this group to take to a desert island, this would be the one.

The original iteration of the King’s Singers comprised counter-tenors Nigel Perrin and Alastair Hume, tenor Alastair Thompson, baritones Simon Carrington and Alastair Holt, and bass Brian Kay (who after leaving the group in 1982 became a successful presenter on BBC Radio). They are the ones singing on this album (and pictured above).

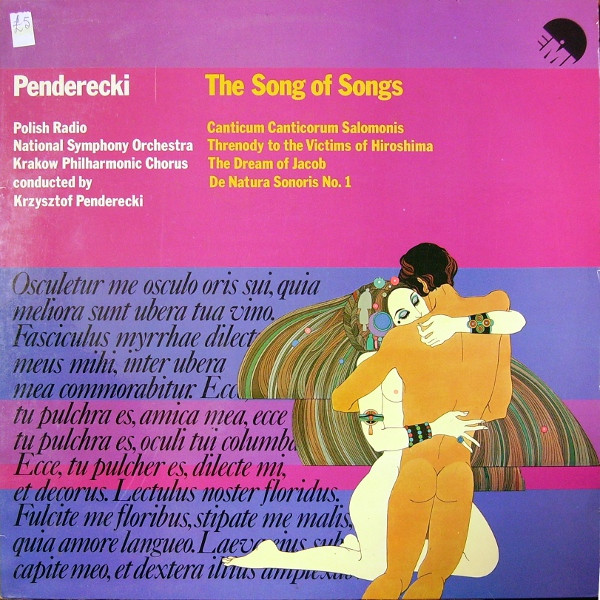

The record was issued as part of a special series of recordings by EMI that focused mainly on new music. (Decca also launched its own series of new music records during this time, under the banner “Headline”). All the album covers featured a striking pattern of varicolored stripes. Amongst the highlights of the series was a superb set of recordings of works by the great Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki (also conducting), including his First Symphony, Magnificat, The Song of Songs and the groundbreaking string composition Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. This recording of The Dream of Jacob was used extensively by Stanley Kubrick on the soundtrack of The Shining. These remain benchmark recordings of Penderecki’s early works.

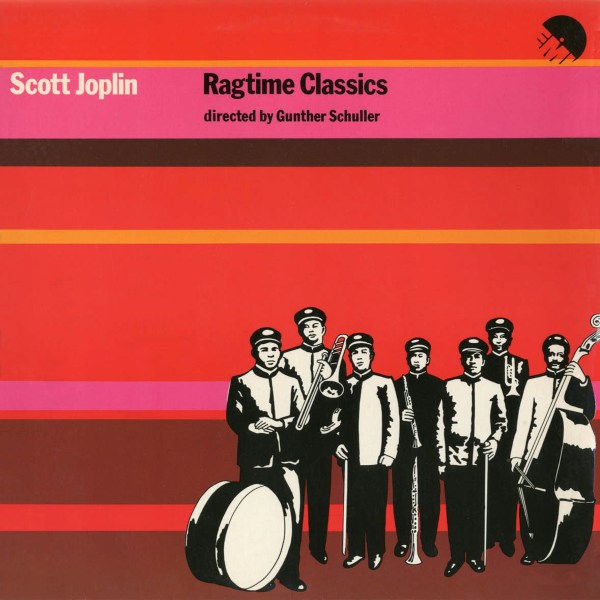

Another standout record in the series was an album of Scott Joplin performed by the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble conducted by Gunther Schuller, a major figure in American music during the 20th century, especially in the realm of fusing jazz with classical.

As you would expect from a series of commissions from living composers of this period, the works on “Contemporary Collection” embody a wide range of compositional techniques, from highly experimental and avant-garde to more accessible tonal fare. It is this variety - and the spectacular vocal execution - that makes the record so engaging, and an excellent through-listen.

The album kicks off with the utterly beguiling and delightful Musicians of Bremen, a retelling of the Grimm Brothers’ fairy-tale using a basically tonal idiom (though modal in nature), but allowing for a wealth of fun vocal effects that capture both the character of the animals, and also the uproarious high-jinks that ensue after they encounter a group of n’er-do-well ruffians.

SIDEBAR: modal music is structured around scales in which there are no accidentals (ie.“sharps” or “flats”). This means that modal music doesn’t have as strong a sense of being in one “key” (ie. C major or C minor) as regular tonal music. It feels like it is floating between keys, and dissonances sound less pronounced. It was a form of tonality we associate with medieval music, and was the idiom in which the first multi-part, contrapuntal music was composed in Notre-Dame in the 12th century by Leoninus and Perotinus. The style was picked up in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by composers like Debussy and Ravel, who wanted to explore an alternative to the intense chromaticism of the late-Romantics like Wagner. Jazz pianist Bill Evans was a keen proponent of modal processes, as can be heard in his album with Miles Davis, “Kind of Blue”. The use of modes is what helps to give that album its sense almost of floating, and perpetual motion.

Australian composer Malcolm Williamson started out his career fully in thrall to Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique, but came around to a more conventional tonal idiom later in life. He was a great admirer of Benjamin Britten, and you can hear Britten’s influence here both in the choice of an accessible children’s story as his subject matter, and in his imaginative setting of the text, full of evocative word and musical play - and, yes, animal noises.

Four animals - a dog, cat, donkey and rooster - have reached the end of their useful working lives on their respective farms, and rather than fall victim to the abuses of their owner, they decide to set out for the town of Bremen where they can live in freedom and become musicians. The story tells of their chance encounter en route with a group of villainous thieves, whom they send packing in the most delicious fashion.

In the sleeve notes Williamson writes: “We all at some point wish we could shed our ties and become gypsies, many of us are forced at some time to become refugees. The animals are both - the unwanted vagrants of the world trying to find for themselves a useful activity. That they should unwittingly dislodge the wicked barons of power and establishment strikes a chord of satisfaction in out hearts….

“The music began in very complicated shape, and the simplifying and blanching of the original materials took me more time than the actual composition of the first version. As it is in the final version, there is a superimposition of mode upon mode, and not a single accidental in the entire work.”

Malcolm Williamson’s musical dramatization is every bit as musically colorful and engaging as you would hope it to be, and is the perfect vehicle to show off the King’s Singers’ vocal virtuosity.

Daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson (c. 1846/47) in the only known authenticated portrait of her as an adult

Daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson (c. 1846/47) in the only known authenticated portrait of her as an adult

Winter Afternoons is a haunting setting of three poems about death by the American poet Emily Dickinson, composed by British composer Peter Dickinson (no relation). The King’s Singers are joined by a double-bass player (often a feature of their concerts), and the instrument’s dark sonorities and the composer’s imaginative use of harmonics add an extra dimension to the evocative settings.

Dickinson: “I gave John Gray (the bass-player) the seven two-part chords in harmonics, which are heard just before the voices enter….their bell-like sound admirably fitted the text and I derived the main material of the piece from these chords. The opening, wide-spaced melody on the bass comes from them, so do the first counter-tenor notes and the unaccompanied section near the end.”

The work beautifully exploits the tonal differences between lower and upper voices, even when the setting moves into an almost hymnal style in the second poem. The final poem uses pizzicatos (plucked strings) in the bass; then halting chords of the voices and bass blend together for the description of life ebbing away. The music slowly gives up the ghost as life is reduced to a series of broken phrases and words:

The Flesh - Surrendered - Cancelled -

The Bodiless - begun -

Two Worlds - like Audiences - disperse -

And leave the Soul - alone -

Side one ends with Ecloga VIII, a setting by the aforementioned Penderecki of a passage from the Roman poet Virgil’s cycle of dramatic poems which helped establish his reputation during the reign of Augustus Caesar in the century before Christ.

Mosaic of the poet Virgil (c.)

Mosaic of the poet Virgil (c.)

Virgil’s text tells of a woman, frustrated in love, using sorcery to win her lover back. Anyone familiar with Penderecki’s early idiom, which reached its apotheosis in the St. Luke Passion (1966), will recognize the battery of unconventional vocal techniques used to create a vivid sense of emotional turbulence and magical conjuring. Frequently the text disappears into the assorted whisperings, shouting, breathing, humming, hissing, gibbering etc. that dominate the work, along with challenging, often micro-tonal, part-singing. The music truly conjures up a sense of hair-raising sorcery, but for me - a huge fan of Penderecki - ultimately it lacks the substance of other works from this period, before the composer turned to a more conventional tonal idiom. Needless to say, the performance is spectacular.

Side 2 opens with what, for many, will be the standout on the record - a work that became a staple of the King’s Singer’s live performances, and which I heard them perform at one of their concerts. Time Piece, by the British composer Paul Patterson, takes as its subject the story of Adam and Eve, and the Fall of Man, though reimagined from a perspective that holds even more resonance today than it did in the mid-1970s.

“It is unjust that an apple should be held responsible for the Fall of Man,” writes Patterson in his sleeve notes. “Clock-watching, chasing the hands of a clock, chasing our tails - the antithesis of Peace - seem to be fallen Man’s eternal punishment; so why not let a wrist-watch and not an apple symbolize our fall from Paradise?”

Following in the long shadow cast by Haydn’s vivid musical depiction of order being created out of chaos at the opening of his 1798 oratorio The Creation, Patterson uses his limited resources of six voices in the most imaginative way. to evoke the creation of the world. This echoes Penderecki’s techniques, but applied in a more focused manner to tell a clear story in sound. It’s quite brilliant.

Writes the composer: “The world is mysteriously born from a single thread of sound slowly weaving its way over two minutes to sweet sounding paradise. After a biblical reference to the creation of the world we hear a rather less biblical reference to the fact that paradise is looking cool.

“All is well we discover until Eve asks Adam what he is wearing on his wrist. The whole subject of time rears its ugly head, and shatters the peace of paradise. This is followed by a mechanical section in which we hear the sounds of clocks, many references to time and time pieces as Adam tries to get Eve interested in the Rhythm of Time…. Paradise is O.K with a watch to measure the day…. This section introduces comical effects, the use of mock spirituals, clocks winding up to a climax in a mechanical fugue, at the end of which God calls a halt to all clocks, and peace returns to paradise as at the start.”

Adam and Eve were doing fine

Till Eve asked Adam the time

Everything about Time Piece - with a sharp text by Tim Rose Price - is absolutely delicious, including the fact that in this retelling Eve is absolved of the responsibility for expelling Man from Paradise, undoing millennia of baked-in misogyny. Here the responsibility for our fall from a state of grace rests firmly on Adam’s head. Our ambivalent feelings about, and relationship with, Time, and the devices that map out every second of our lives, are the perfect substitute for answering the eternal question of why life sucks. Was Eden really such a bad place to eke out our days?

At the time of this work’s commission - 1973 - the first digital watches came onto the market, and they soon came to epitomize for many everything that was wrong with certain of our technological obsessions (as does the smart phone today). As Douglas Adams opined in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy only a few short years later:

“Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun. Orbiting this at a distance of roughly ninety-two million miles is an utterly insignificant little blue green planet whose ape-descended life forms are so amazingly primitive that they still think digital watches are a pretty neat idea.”

Time Piece ends with a return to apparent peace in Eden, but we all know it’s only a matter of time before things change for ever. Echoing the call of British publicans at closing time across the land, the work concludes - in a suitably equivocal manner - thus:

The world was all wound up.

Time, gentleman, please.

Iris at the House of Sleepe

Iris at the House of Sleepe

The final work on Contemporary Collection could not be more different, but is equally mesmerizing, a tour de force of vocal part-writing and performance. The House of Sleepe is a setting of one of the more hallucinatory episodes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid, like Virgil, lived during the reign of Caesar Augustus. Immensely popular in his lifetime, he nevertheless incurred sufficient wrath from the Emperor to be banished to Tomis on the Black Sea for the last ten years of his life. The reason for this remains shrouded in mystery.

The Metamorphoses, Ovid’s most famous work, retells key episodes out of mythology in which characters are transformed from one state, or one shape, into another. These were certainly my favorite Latin texts to study in school: it was hard, even for the most lowly Latinist such as myself, not to respond to the richness and rhythm of the language, and the vivid manner in which Ovid tells his tales. It sure as hell beat wading through Julius Caesar’s commentaries on his various campaigns or the vast swathes of Virgil’s account of the Trojan War we had to “translate and construe”. Needless to say, there have been many fine (and not so fine) translations of Ovid over the many centuries since the Metamorphoses were written, and in this work, Bennett selects a famous 16th century translation by Arthur Golding, whose work was well known to Shakespeare (and used as source material in a number of his plays, including Titus Andronicus and A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

Reading the text of The House of Sleepe will have you convinced that both Ovid and Golding were tripping on some seriously strong hallucinatory substance. I cannot think of a more vivid representation of the sleep state in literature; it makes Keats’s To Sleep (“O soft embalmer of the still midnight…”) - set so memorably to music by Benjamin Britten in the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings - sound like a nursery rhyme in comparison.

Bennett rises to the occasion with a setting that is mired in endless chromatic phrases that seem to endlessly turn in on themselves. From the opening lines sung by solo tenor you are pulled in to the story of Iris, Goddess of the Rainbow, messenger of the greater Gods, descending into the House of Sleepe…..

Dame Iris takes her pall wherein a thousand colours were

And bowing like a stringed bow upon the cloudy sphere

Immediately descended to the drowzy house of sleepe,

Whose court the clowdes continually do closely overcreepe….

Richard Rodney Bennett (1936-2012) remains one of the most underrated British composers of his time, no doubt owing in part to his chameleon-like abilities to write in a wide range of genres - embracing both classical and jazz - without a more instantly recognizable style of his own. Naturally he flourished as a film composer, writing memorable scores for films as varied as Billion Dollar Brain (1967), Ken Russell’s entry in the Michael Caine/Harry Palmer series of spy thrillers, Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and Murder on the Orient Express (1974), the last two of which were both nominated for Best Dramatic Score Oscars. He even made albums of standards as a solo singer.

Richard Rodney Bennett

Richard Rodney Bennett

In his youth, Bennett studied with the top European avant-gardists at Darmstadt in the 1950s, and furthered his forays into serialism as a student of Pierre Boulez, though ultimately he composed primarily in a tonal idiom.

The score for The House of Sleepe is a brilliant example of small vocal ensemble writing, capturing all the coloristic imagery of the text in music that moves in lock step with the words, effortlessly shifting from hallucinatory chromaticism to more declamatory passages. It manages to be both dramatic and abstract at the same time, which is exactly what the text is too. The virtuosity of the performance is staggering, especially when you realize this would have been performed live regularly by the group. We’re a long way from madrigals here.

As the tale wends its way to its conclusion, there is a distinct feeling that Iris may never escape the clutches of eternal sleep. Those returning, weaving chromaticisms threaten to pull her under, but she does manage to escape - literally embodied by a solo voice escaping the vocal mire by reaching out to a single high solo note on the final word “clyme”….

……… Hir message being told Dame Iris

Went her way, she could her eyes no longer hold from sleepe.

But when she felt it come she fled that instant tyme,

And by the bowe that brought her downe, to heaven again did clyme.

There is something for everyone on this album, be you a fan of 20th century modernism, or novelty material done with genuine wit and musicianship that never panders or takes the easy way out for cheap effect. This is material that stands up to the test of time: I’ve been listening regularly to this record since it was released in 1975, and it hasn’t dated at all (except, perhaps, the Penderecki - a little bit). If I had to choose one King’s Singers album for my desert island, this would be it. Their performances are staggering in their casual virtuosity. The recording is everything you would want it to be without going to the next level: natural sound and perspective, each voice clearly heard within a well-blended ensemble. Some might find the countertenors occasionally a little strident (I don’t). This was a time when this vocal type was just beginning to come into its own; today’s practitioners veer towards a more rounded and darker tone which is easier on the ear.

At the very least, take a listen to Time Piece below (first track on Side B). I guarantee you’ll get a kick out of it.

Never issued on CD, insist on an English pressing - and there should be plenty around. Avoid American and other foreign pressings which will more likely than not be cut (with variable degrees of finesse) from a second generation copy of the master. The vinyl itself may have some tics and pops even after a thorough cleaning - typical of this period on this label - but nothing you can’t live with.

What to Listen To Next:

There are so many great records of the King’s Singers on EMI from this first period of their international success, most of which have never appeared on CD. You can go for the more traditional classical albums like A French Collection (1973), which includes some glorious Poulenc as well as older chansons, or Madrigal Collection (1974), again featuring Renaissance songs. There are several “light music” collections, Out of the Blue (1974) and Keep on Changing (1975), in which the group covers various pop hits, which are an acquired taste, but great fun if you leave your musical judgments at the door. (My guilty pleasure is so-called “easy listening” records, many of which feature superb arranging, playing and sound, so I have no problem spinning these when I want to torture my neighbors or a visiting friend).

But the one King’s Singers record from this period that I think is essential apart from Contemporary Collection is The King’s Singers sing Flanders & Swann and Noel Coward (1977), a brilliant tribute to a gaggle of essential musical humor, very British in flavour.

If you want to hear the musical precursors to Monty Python’s Lumberjack Song, listen no further. The arrangements are stellar, fully catching and even improving upon the lyrical and musical wit of the originals. Here’s a sample of Noel Coward on top form - just wait for the song’s punchline concerning a certain sailor from Venezuela:

Today, the current iteration of the King’s Singers is releasing one superb album after another on Signum Classics, and I will shortly be reviewing the exquisite collection of music by William Byrd and Thomas Weelkes (and a few surprises) they recorded with the viol ensemble, Fretwork. The musicianship, as with all the group’s albums, is impeccable. Fifty years on, the King’s Singers remain the gold standard of a cappella singing.

The King's Singers: Contemporary Collection

Recording Producer: Christopher Bishop

Balance Engineer: Robert Gooch

EMI Records 1975 EMD 5521

Music: 9 Sound: 8

.png)