Classic Candid Albums Reissued By Exceleration Music

Mastered By Bernie Grundman

In 1960, Cadence Records created and funded a subsidiary, Candid Records so that Nat Hentoff, a writer and non-musician with no music business experience could do the fun stuff and be an Artists & Repertoire director/ jazz record producer. Hentoff (1925-2017), a jazz fan since his early teenage years, had enthusiasm as well as a love for and a deep knowledge of the music. He was a former jazz DJ, a former editor of Downbeat, a former editor of his own jazz magazine, had co-written one of the best books about jazz, "Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya", and had written dozens of LP liner notes. All that makes for an admirable resume but one that noticeably lacks the one quality that record companies valued above all others in an A&R director/record producer—proven ability to find and record commercially successful artists.

Cadence hired him anyway and Hentoff’s tenure at Candid was a dismal commercial failure. His plan for the label seemed to be to only record artists who were controversial or avant-garde or little known, sometimes two of the three and in the case of Cecil Taylor, all three. There is not a record in the Candid catalog, that in the jazz market of 1961, would be a certain strong seller; no organ records, no piano trios playing standards for cocktails, no bluesy, funky Silver/Blakey style groups.

That Cadence would set up Candid and put Hentoff in artistic control is so strange and foolish that it’s more than puzzling, it’s outright mind boggling. Consider the facts. Cadence was an independent label that had experienced great commercial success with the Everly Brothers, Andy Williams and a few teen oriented pop acts. The rest of the label’s catalogue, other than a one-off 45 of Link Wray’s “Rumble,” consisted of the typical late 50s fare---adult pop, easy listening, mood music and novelty records. Uncategorizable pianist, Don Shirley, the subject of a recent controversial movie, was Cadence’s only instrumentalist that was even a moderate seller. Cadence didn’t record jazz, classical, blues, gospel or R&B and, except for the Everly Brothers, probably had the blandest, most boring catalog of all the successful 50s independents.

Yet for some, now unknown reason, this corporate purveyor of soulless, white bread, commercial pablum, decided to start a jazz subsidiary and give free rein, as artistic director, to Hentoff who had made obvious in many reviews his disdain for commercialism and preference for modern, adventurous, even avantgarde jazz. Cadence couldn’t possibly have believed that Candid would be profitable with Hentoff in charge. All I can suggest is the universal explanation for irrational business behavior---the I.R.S. and taxes.

Did a clever accountant point out that a lot of Everly Brothers money was going to be paid to the I.R.S., unless it got spent? Follow the money. The Everly Brothers left Cadence in 1960, Andy Williams left in 1961 and corporate profits must have taken a precipitous dip. Candid lasted less than a year and folded midway through 1961. Coincidence?

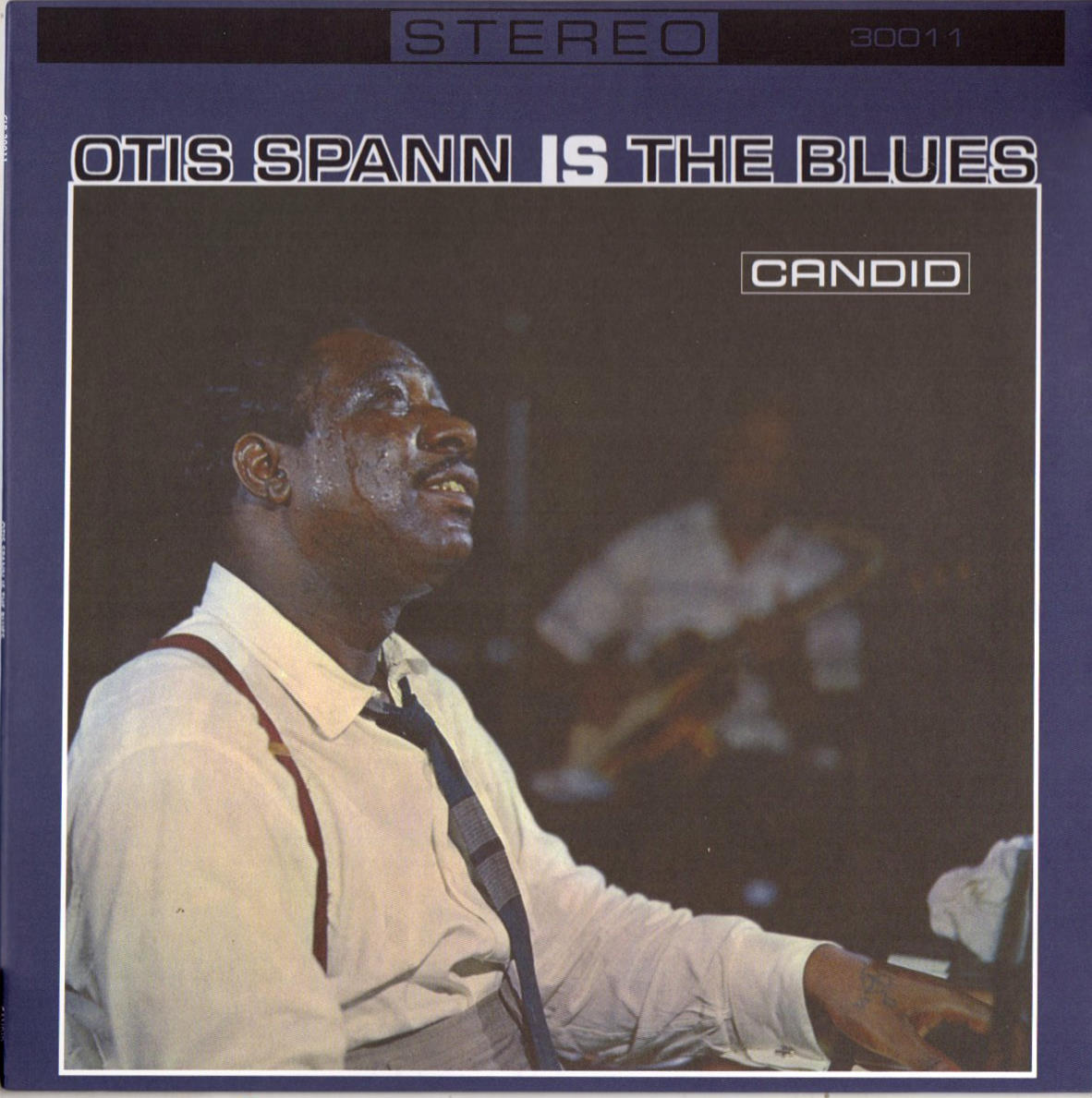

Otis Spann Is The Blues---Otis Spann Candid CLP 30011

Hentoff started Candid off in what would become his usual “I’m recording what I want and I don’t give a damn about sales!” style by recording Otis Spann on August 23, 1960. Spann (1930-1970) was a blues pianist/vocalist whom Hentoff had heard as part of Muddy Waters’ electric backing band at the Newport Jazz Festival the month before (note: electric instruments five years before Dylan). He was nearly completely unknown outside the blues bars of Black Chicago and though, Spann had recorded two obscure singles and four tracks for a then unreleased U.K. blues compilation, this was his first album recording session.

The intended market for Candid LPs was urban, generally college educated, young white people who, if they bought blues records, bought acoustic guitar oriented “folk blues,” like Leadbelly, Broonzy, or Terry and McGhee. Spann was not a “folk blues” artist, but a “Chicago blues” artist which was much different. Chicago blues was a loud, aggressive, urban dance music played with electric instruments in neighborhood bars for Black people who were frequently migrants from the south. No record company had tried before to sell an album of uncompromised contemporary Chicago blues to a white audience.

If recording an obscure Chicago bluesman was not daring enough, Hentoff showed his complete disdain for marketing and the sensibilities of folkies by pairing Spann with the electric guitar of Robert Junior Lockwood. Lockwood, one of the greatest electric blues guitarists, was a stalwart Chess sideman who had backed Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson and many others on dozens of sessions, as well as being a recording artist in his own right. While the album is credited to Spann, it is really a duet album and the complete musical compatibility of the two men is a testimony to Hentoff’s knowledge of blues styles.

Spann was a powerful two-handed pianist, playing boogie or insistent “slow drag” rhythms with the left hand, while his right, one of the most facile in blues, played cascades of melodic variations. He was also a limited but effective singer with a hoarse, soulful, “telling you my true story” voice. “Beat Up Team” sounds like it was made up in the studio, probably in response to a Hentoff request to “sing something about life in the South on a farm.” Spann’s bitterly angry vocal makes for a powerful emotional experience. Probably as a tribute to the man who was his main pianistic influence, Spann sings Big Maceo’s song “Worried Life Blues” (incorrectly credited to Spann) and after three verses of dark, sleepless at 4 am despair, he and Lockwood play an incredible instrumental 36 bar break that is jazz-like in its simultaneous improvisation.

Lockwood claimed to have been taught guitar by Robert Johnson who was his mother’s boyfriend. He sings four songs on the album, one of them— “I’ve Got Rambling On My Mind” written by Johnson and one---“Take A Little Walk With Me,” reputedly written by him, and all of them are masterful. Lockwood’s playing here is his own jazz influenced, electric modernization of Johnson’s style. His vocals lack the eerie charisma of Johnson’s but are gritty and honest with an appealing jazzy rhythm feel.

Otis Spann Is The Blues is not “party blues.” It may not feature the rocking, burning guitar of Albert, Freddie or B.B. or the blues rock gods, but it is one of the great “listening” blues albums.

I was able to do comparative listening with my stereo Candid original pressing, a Barnaby 1970s reissue and the Exceleration reissue. To my ears, the Exceleration LP sounded smooth and well balanced tonally. The midrange was warm and expansive, maybe because the high end seemed a bit muted. The recording does not have a lot of bass and what was on the LP was somewhat thin. The Exceleration was an enjoyable listen and a solid reissue but not magical.

I thought the original Candid stereo issue was far superior. Most noticeable was more ambiance, “air” and low-level detail. The instruments seemed to be playing in the same space. Dynamic range was wider. Spann’s hammered treble runs rang out quicker and louder. The treble was slightly more extended. The guitar was also louder. It could be said that the on the original LP the guitar was slightly too loud, but I preferred it that way.

The 1970s Barnaby issue was very similar to the original Candid, except for a very slight overall haze. Possibly, a copy tape was used or my LP was pressed from worn metal.

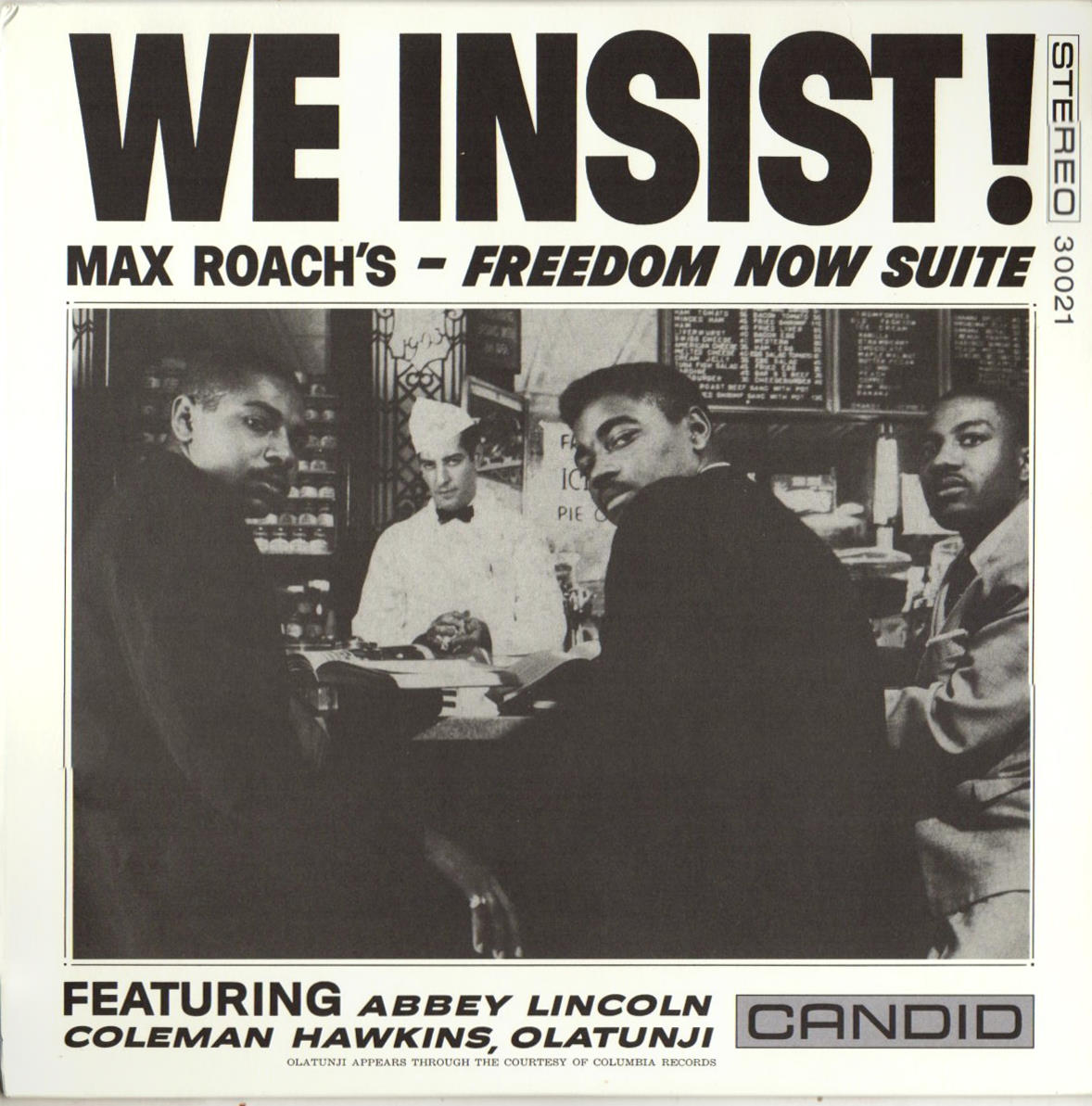

WE INSIST!—Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite---Max Roach Candid CLP 30021

On August 31 and September 6, 1960, Hentoff was back in the studio, this time with Max Roach (1924-2007) to record WE INSIST! Max Roach’s-Freedom Now Suite. I think it is safe to say that in 1960, no A&R director other than the politically committed Hentoff would have recorded and no label other than Candid would have issued, WE INSIST! Max Roach was then under contract to Mercury Records and in the “by permission” fine print on the back of the album, he is listed as “an exclusive Mercury artist.” Apparently, he was exclusively on Mercury except when he wanted to record politically controversial music.

In my recent Tracking Angle article on Randy Weston’s Uhuru Afrika, an equally political album, recorded two months later, I discussed in some detail, the anger of Black Americans in 1960 and the reluctance of the record companies to allow their Black artists to express that anger. Hentoff not only recorded Roach’s music, which politics aside, was challenging for 1960, but issued the record with the cover’s angry block letters, exclamation point and accusatory photo which made many distributors and stores refuse to stock the record and radio stations ban play of it. Hentoff also wrote the liner notes which are forthright in their support for Roach and the civil rights movement.

WE INSIST! is a five-part suite that celebrates African nationalism, African culture and African pride with poetry, singing, jazz soloing, African percussion and adventurous, post-bop music. Sixty plus years later, it is still challenging, angry music, far from a finger popping while doing the laundry or a drinks and dinner listen.

Roach’s suite while not musically complex was very emotionally demanding and the band he put together played it with fire and fury. The great tenor saxophonist, Coleman Hawkins, a jazz star since the twenties, was fifty-five years old, nearly twenty years older than Roach but adapted to the avant-free/modal setting and played superbly. On “Driva’ Man,” a song about the overseer during slavery, after the barely suppressed rage of Abbey Lincoln’s vocal, without a piano and over the loose rhythm and simple harmony, he plays a long sorrowful solo, staying for him, unusually close to the melody, sounding a lot like Sonny Rollins when he was Way Out West. The astonishingly gifted twenty-two year old trumpeter Booker Little plays Roach’s melodies with his beautiful tone, and solos on “Freedom Day” with the facility of Clifford Brown while hinting at advanced harmonies. It was one of the great losses to jazz when Little died of uremia slightly over a year later. Trombonist, Julian Priester, on “Freedom Day,” plays a jubilant, wailing, JJ Johnson with an edge solo.

Abbey Lincoln’s singing on We Insist! is among the most innovative performances in the jazz of the 1960s and “Triptych—Prayer/Protest/Peace”, a duet between her vocals and Roach’s drums still has the power to shock. Over Max’s melodic, conversational, free, but never losing the time feel, drums, Abbey shouts screams, moans, sighs, sings wordlessly, and somehow breathes beautifully. On “Prayer,” she sounds like a gospel singer; on “Protest,” she creates the template for hipster cult icon Patty Waters’ “Black Is The Color,” on “Peace,” she improvises freely. Sixties free jazz and spiritual jazz begin with “Triptych”.

I was able to compare an original Candid mono pressing of WE INSIST! to the Exceleration reissue. On the reissue, the treble was slightly thin and a bit harsh at the top. The midrange was smooth but not overly warm and really quite enjoyable. Bass was not particularly deep or powerful. Overall dynamic impact was slightly lacking, especially noticeable on the drums. On a record featuring so much percussion that was a considerable negative. While a pleasant listen, the reissue didn’t deliver the excitement and drama of the original. Like Spann Is The Blues, the original WE INSIST! had much more air and better dynamic range. Even in mono, the instruments seemed to be placed more solidly in the soundstage. Treble was more extended and fuller. Cymbals sounded sweeter and more melodic. The original was a more powerful and exciting listen.

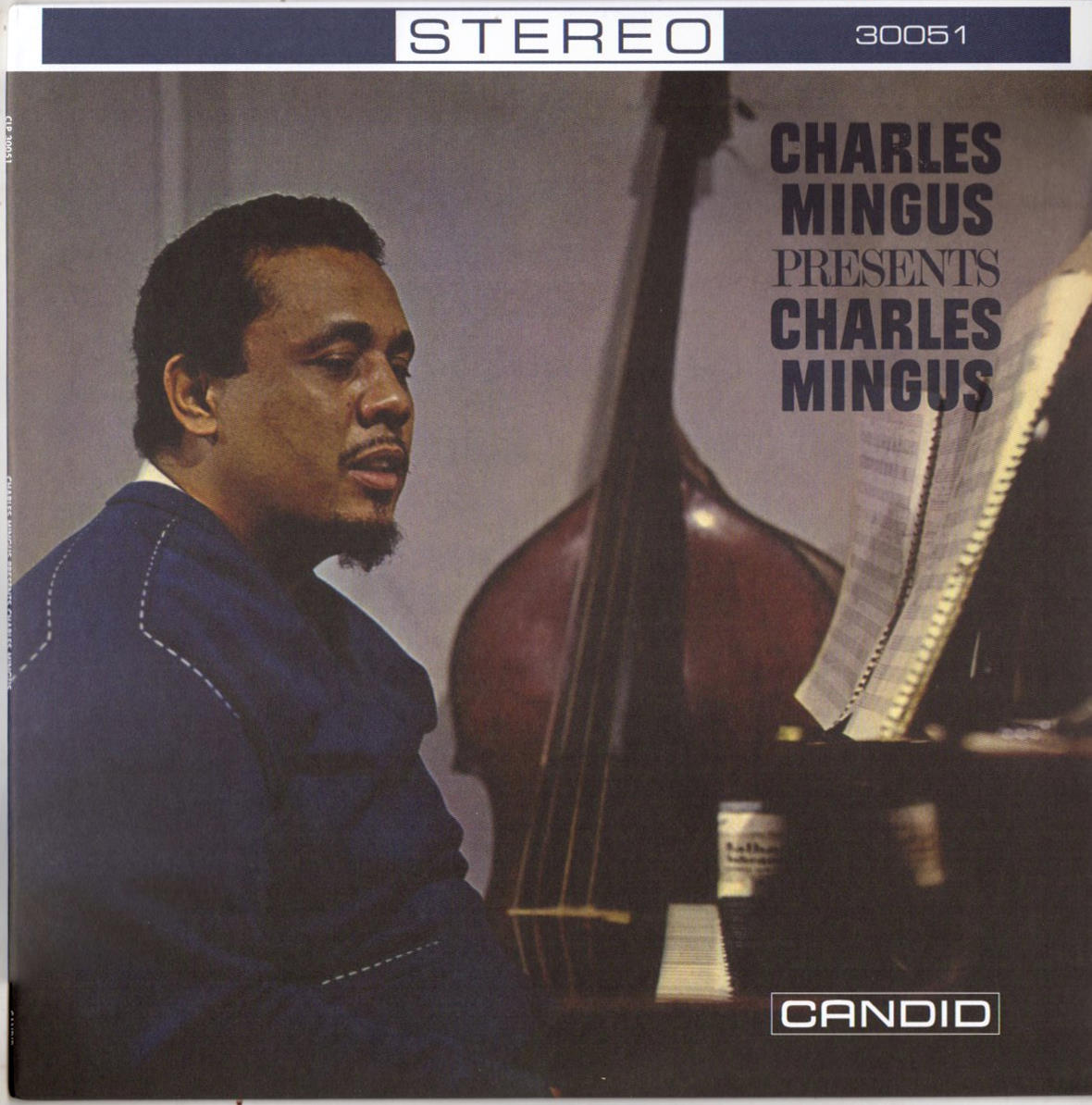

Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus---Charles Mingus Candid CLP 30051

On October 20, 1960, Hentoff produced the greatest Candid album and one of the all-time jazz masterpieces—Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus. The volatile Mingus (1922-1979) considered Hentoff his friend and would call him on the telephone, to play new compositions and ask for an opinion. When Mingus was in the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital, it was Hentoff he called to help get him out.

Playing jazz is playing music in the moment. The musician’s mood, the atmosphere, the place, the audience all affect the music. Mingus had recorded for big time, prestigious label Columbia the year before. The producer, afraid of political repercussions, refused to let Mingus record “Fables of Faubus” with the words. The music recorded for Columbia is excellent but a bit subdued—Mingus isn’t being Mingus.

Being in the studio with Hentoff was different. Mingus recorded his merciless mocking of segregationist Arkansas Governor Orville Faubus. “Oh, Lord, no more Ku Klux Klan…. Name me someone who is ridiculous---- GOVERNOR ORVILLE FAUBUS!,.....Two, four, six, eight they brainwash and teach you hate.” The album is structured like a club set with Mingus’ apparently unrehearsed intros to the songs and admonitions to the imaginary nightclub audience to refrain from shaking the ice in their glasses. Mingus is presenting Mingus unfiltered with no record company producer B.S.—“You can’t say that.”, “Don’t play that it’s too far out.” “You can’t play jazz without a piano.” “What the hell is that alto player doing? Tell him to stop screeching.”

The music is wild, funky, soulful, beautiful, funny, dark, joyous, crazy, angry, sensitive, tender and inimitable. It’s also serious, complex and played with astonishing virtuosity. Eric Dolphy in 1960 was at the forefront of the jazz avant-garde and his playing here is at a level of jaw dropping technique and creativity that few have ever reached. The cry and wail in his playing is the voice of Mingus’ music. They were born soul twins to make this music together. Mingus’ bass playing manages to swing and groove hard while playing melodic lines and prodding and pushing the soloists. All the virtuoso, interactive bass playing of the 60s-LaFaro, Peacock, Gomez, Davis etc. etc. is presaged by Mingus’ playing on this album. Ted Curson, a fine trumpeter who never reached the front rank, plays very well in a hard bop style with touches of sixties freedom. The underrated drummer, Dannie Richmond, holds down the time and swings hard, allowing Mingus the freedom to push and pull and spar with the soloists.

Presents Charles Mingus, for 1960, was a very adventurous, uncompromising album. By omitting a piano, using pedal points, simultaneous soloing, voice-like saxophone sounds, long solos with harmonic and rhythmic freedom, it pointed the way toward the free jazz of the 1960s. That makes the album sound intimidating and dryly intellectual. It’s anything but—it’s a shake your ass, shake your soul masterpiece.

I compared the Exceleration issue to my original Candid stereo pressing. My conclusions were similar to those made earlier in this review. Exceleration---smooth midrange, lacking a bit of bass, cymbals didn’t ring out and lacked sweetness. Overall, a good enjoyable listen. Original—more air and better image solidity. More dynamic range. More excitement, wilder, just more Mingus. I also compared my copy of the Mosaic Complete Charles Mingus Candid Recordings which was mastered by Rudy Van Gelder. RVG, as he was wont to do in later years, mixed the wide stereo spread to near mono. I didn’t like the hybrid mono result at all and the midrange seemed to blare.

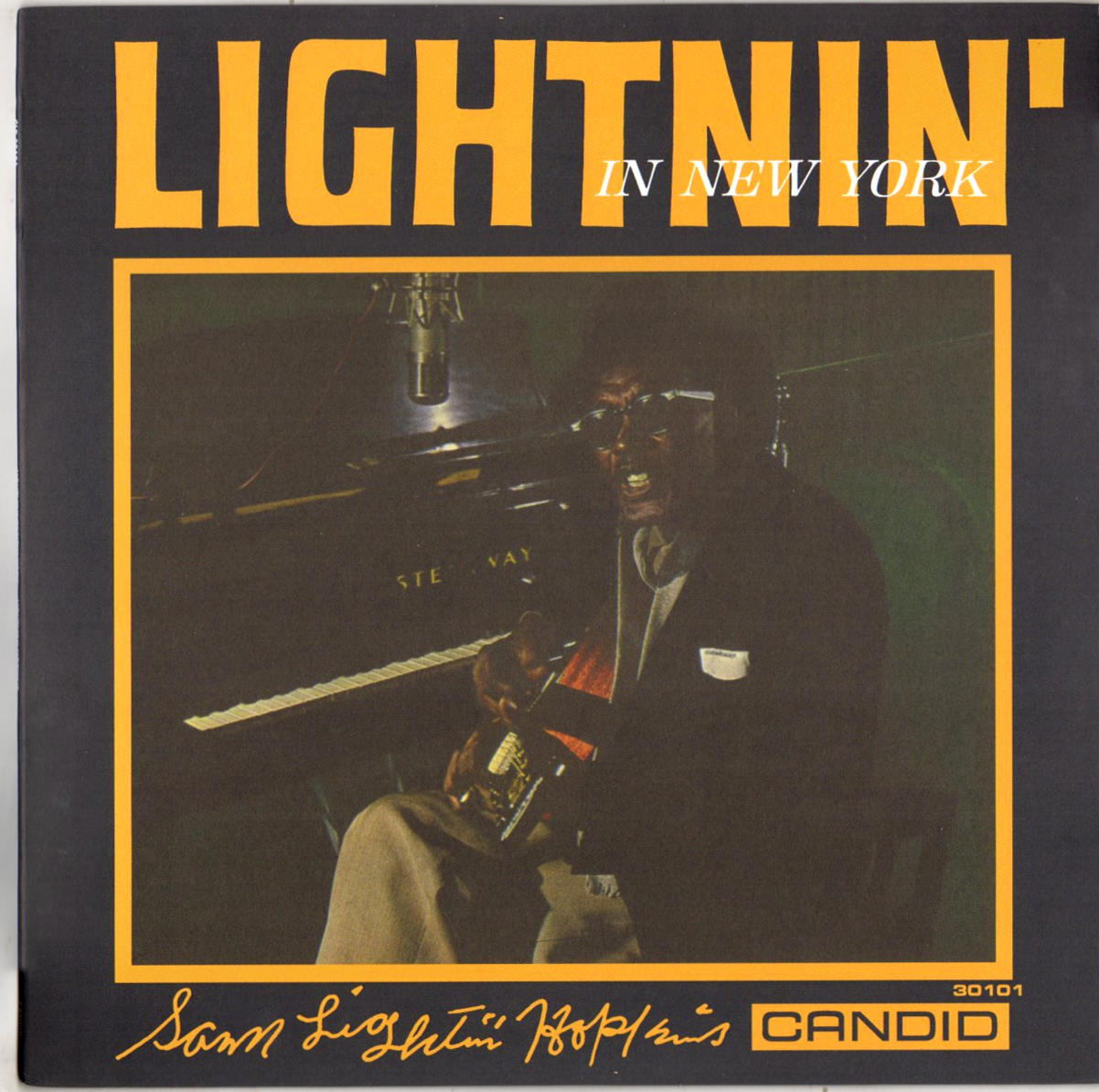

Lightnin’ In New York---Lightnin’ Hopkins Candid CLP 30101

Hentoff was in the studio again on November 15, 1960, recording, Lightnin’ In New York, a solo album by Texas blues guitarist and occasional pianist, Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins. Hopkins (1912-1982) became a wandering itinerant guitarist/ blues singer in his early teens, playing on street corners, in bars and for parties. He hoboed and played throughout Texas, rambling as far as California and Yazoo City Mississippi, augmenting his music income with farm work when times were tough.

In 1946, he made his first recordings in Los Angeles, playing the same unadulterated Texas blues style that he had been playing for two decades. The records were aimed at the downhome blues market in Texas and southern California---Black people living in rural areas and Black people who had migrated from the country to cities to get jobs in the post-war economic boom. Hopkins made dozens of 78s and his records became jukebox hits in bars in Black neighborhoods. In Houston, his home base, he became a local celebrity and star attraction in the clubs and taverns of the Fourth Ward, the heart of the Black community.

In 1959, Hopkins’ life and career were to change dramatically in what must have seemed to him a strange, inexplicable and unsettling way. Sam Charters, in his groundbreaking book, The Country Blues, wrote a chapter on Hopkins and referred to him as “the last singer in the grand style.” This was completely, absurdly untrue but it was great publicity. Soon, Hopkins was recording an album for Folkways and then one for Tradition. The names say it all. Hopkins was now a relic in the folk museum—the last blues singer.

The heavily amplified electric guitar that he had been using since the early fifties was now replaced by an acoustic. Before long, he was performing for white people in Houston and not long after at UCLA. He made his first trip east to New York in October 1960. Hentoff saw him perform at Carnegie Hall on a bill with Pete Seeger and Joan Baez and reviewed the event with considerable skepticism, writing of Hopkins, “He was the only real folk singer on the program.”

Lightnin’ In New York was one of four albums Hopkins recorded in three weeks while in New York. Material to record was never a problem for him. He had a vast storehouse of songs that he had learned or composed and he had the ability to create new songs spontaneously when picking up a guitar. The Candid album is made up of a few of these improvisations, a few cover versions, songs that were in his performing repertoire, and a story.

Hopkins was probably regularly performing “Might Crazy” and it’s immediately obvious that he earned his living playing for dancers. Over an irresistible boogie groove, he plays some of his favorite licks and sings, about washing clothes, advising to “keep rubbing at that same ol’ thing." Hopkins was a master of the “talking blues” and halfway through the song, while continuing the boogie groove, he tells with superbly dry comic timing, the story of how his Mama and Sis got drunk on wine while doing the wash. Red Foxx and Flip Wilson were lucky he didn’t do standup. Ron “Pigpen” McKernan performed this song frequently in live shows with the Grateful Dead.

“The Trouble Blues” and “Wonder Why” are superb deep blues performances with dexterous guitar playing and beautiful singing. There are two piano numbers, “Your Own Fault” and “Lightnin’s Piano Boogie” and they are lesser performances, hampered by Hopkins’ limited technique and dodgy time feel. Hentoff should have told Lightnin’ that he wanted only guitar numbers. “Mister Charlie” is a long story about an orphan with a speech impediment who finds a home. It really is that corny. Apparently, it was popular with concert audiences. To me it was slightly amusing, the first time, but now a “must skip.” “Black Cat” is a “hidden” track at the end of Side 2. It’s another of those perfect Hopkins boogies propelled by his tapping foot with lyrics about a “white cat and a black cat” who go out drinking “Morgan Davis” wine and get into a drunken verbal dispute. Some internet sources have claimed incorrectly that this tune was not released because of concern over the racial references. In fact, it was released on The Jazz Life a 1961 Candid LP compilation of extra tracks.

Lightnin’ In New York is a good Hopkins album but there are many better. The two Bluesvilles and the Fire album recorded in the same month are better. They were recorded by more experienced producers. I think Hentoff’s “hands off” studio approach was ill suited to recording Hopkins. Hentoff wrote in the liner notes, that “the session went easily.” Too easily, I suspect.

I had a mono original Candid pressing to compare to the Exceleration issue. I’ll try not to repeat too much. The Exceleration was well balanced tonally with a warm, full midrange. No bass and no cymbals on the recording probably helped. The original had as I had come to expect more air, dynamic range and a more solid image. The mono record’s imaging was much more solid and realistic. Why is the stereo mix the default (certain 60s rock LPs excepted)? Why don’t companies reissue the mono mix when it is clearly better?

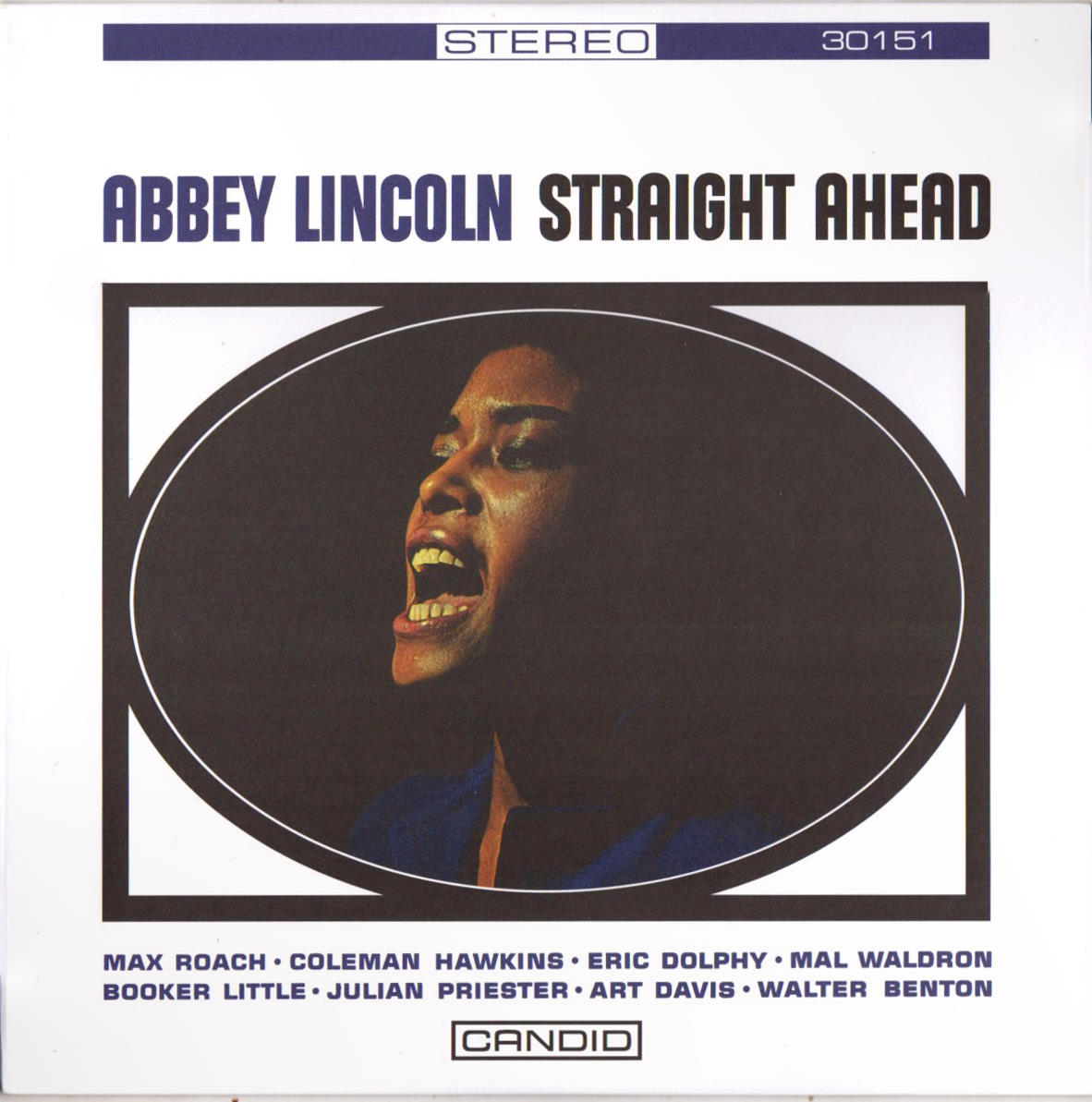

Straight Ahead---Abbey Lincoln Candid CLP 30151

Hentoff begins his liner notes to Abbey Lincoln’s Straight Ahead with the sentence, “Until we were in the studio recording We Insist!, I had not been impressed by Abbey Lincoln’s singing.” Candid indeed. He goes on to comment that at that session, he heard a “new Abbey Lincoln.” Hentoff was a perceptive listener. There was nothing in Lincoln’s prior career which would indicate that she was capable of the passion and improvisational freedom she displayed on WE INSIST!

The singer that had made four albums of standards with very well played but typical jazz accompaniment was a different Abbey Lincoln. That one was a fine Billie Holiday influenced singer who lacked the originality that would set her apart from the dozens of other talented singers on the jazz scene in the late fifties.

The record companies and her management had forced Lincoln into a chanteuse/sex kitten role. Her first two albums had cleavage cover shots. She was told to sing, in her words “the more titillating standards and phony folk tunes…They brainwashed me night after night but I knew that wasn’t me.”

She became romantically involved with Max Roach (they were married in 1962). “I learned from Max that I should always sound how I feel…And I decided that I would not again sing anything that wasn’t meaningful to me.” WE INSIST! and Straight Ahead were the result.

On Straight Ahead, the accompanying band which includes almost all the musicians from WE INSIST! with Eric Dolphy and Mal Waldron added, plays aggressively like it’s a jazz instrumental date, rather than a backing a singer date. Lincoln matches their intensity and musicianship. Throughout the album, she sings in her middle register, speech level voice with an astringent tone and a hint of gospel preaching. She’s no longer the singer of the Riverside albums that strove to sound pretty. She’s a truthteller now.

On Blue Monk, she sings her own Monk approved lyrics about the cost of being yourself and follows Coleman Hawkins’ gorgeous solo with a wordless recapitulation of the melody that is Monkishly a bit wild and eccentric, then bites down hard on the words, “It takes some doin’” while dragging behind the beat. It’s a subtle, masterful bit of singing that makes clear how painful it can be to go your own way.

Her own songs pull no punches. “In The Red” is a song about being poor. The music is harsh and dissonant in free time and Lincoln continually improvises on the melody and the feeling of the lyrics. On “Retribution,” Lincoln says she wants or expects nothing but “Just let the retribution match the contribution, baby” simultaneously commenting on relationships and the struggle for civil rights.

The new Abbey Lincoln created a new kind of jazz singer album on Straight Ahead. There are no songbook standard tunes and she co-wrote four of the seven songs. The lyrics avoid the stereotypical female singer seeking love or bemoaning the lack thereof cliches. Lincoln portrays herself as a strong independent woman with a lot to say and powerful feelings that that she needs to express. Jazz singing before Lincoln had, at its best, been artifice. Singers of talent, even of genius, role playing songs written by professional tunesmiths for Broadway shows or movies. Lincoln eliminated the pretending and expressed herself. Straight Ahead is a singer songwriter album and I think the first in what has become a grand tradition.

On the Exceleration reissue, the horns sounded slightly harsh and edgy. Possibly, the treble was boosted to increase the impact of the voice. On “In The Red”, there was some trebly, edgy distortion which could have been a pressing flaw. On the original mono Candid, LP Lincoln’s voice was fuller, more dynamic and three dimensional. It was a deeper, more emotional listen that the Exceleration

I need to point out that all five Exceleration LPs played with slight noise that was more than occasional but not continuous. The pressings were acceptable but not as good as those of the admired audiophile companies. Of course, the Exceleration LPs can be purchased online for the very reasonable price of approximately $25.

Original Candid LPs are rare and clean copies sell for $100 plus, often for considerably more. If your taste, ranges beyond the jazz mainstream to the adventurous and you enjoy blues, the Exceleration LPs are a good value for the money alternative.

.png)