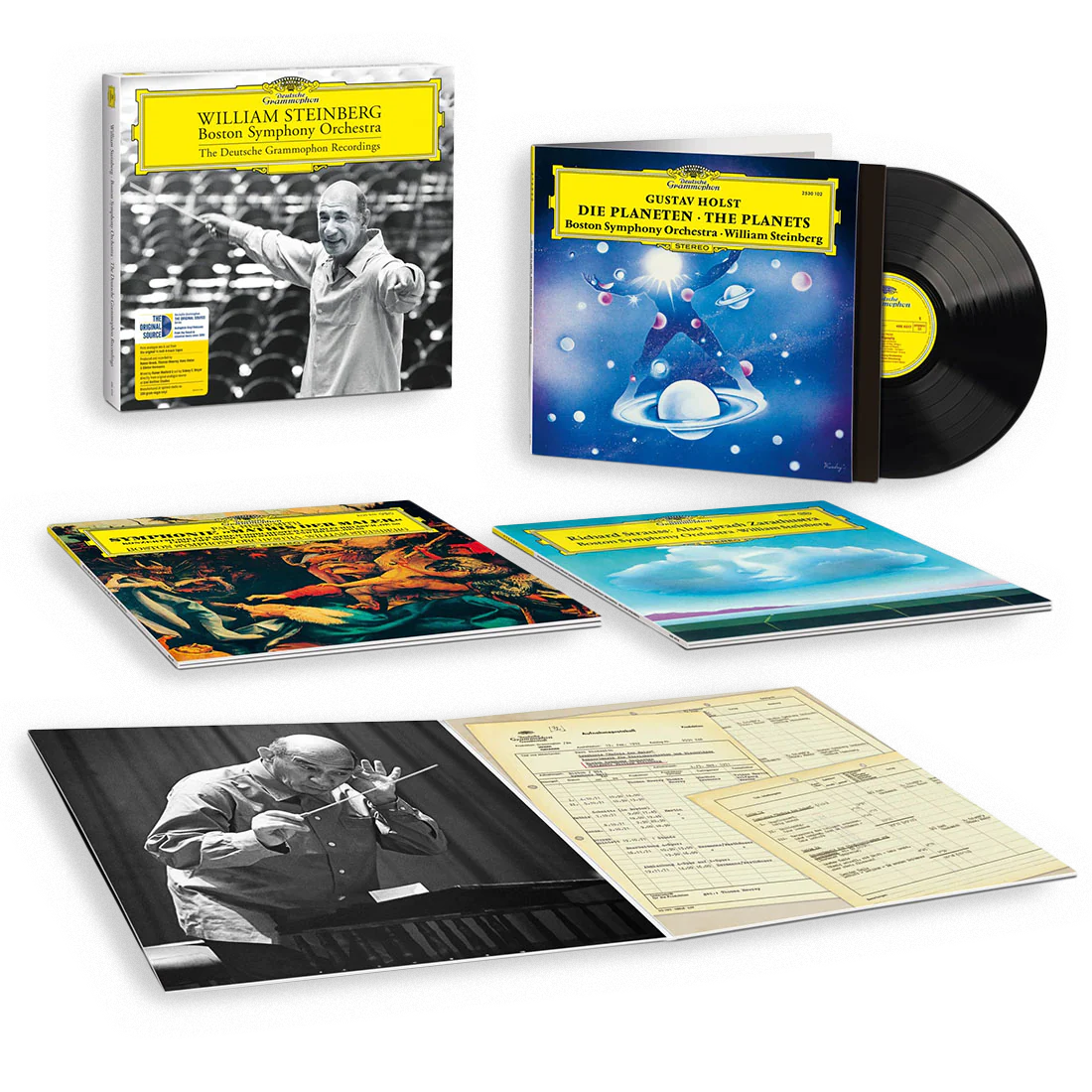

Classic Recordings by William Steinberg and the Boston Symphony Orchestra Are Reborn on Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Vinyl - PART 1: Introduction and "The Planets" by Gustav Holst

Emil Berliner Studios Revitalize DG catalogue gems for a new generation of listeners

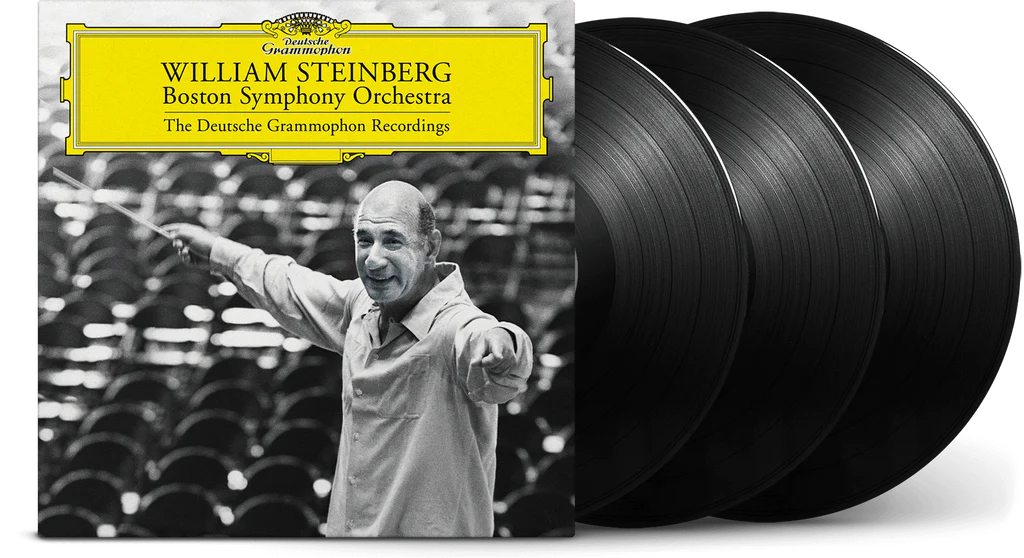

And so we arrive at what I am sure has been one of the most eagerly awaited releases in the Original Source Series vinyl reissue program. (In fact I know it has been: the box is already sold out on the DG site but I am assured that it will be appearing on the usual US retail sites shortly; I imagine a repress of some description is highly likely down the road).

And so we arrive at what I am sure has been one of the most eagerly awaited releases in the Original Source Series vinyl reissue program. (In fact I know it has been: the box is already sold out on the DG site but I am assured that it will be appearing on the usual US retail sites shortly; I imagine a repress of some description is highly likely down the road).

These three records have never enjoyed the high profile of some of their competitors in this repertoire, which is a real shame, because these are very fine performances indeed, and have been recognized as such by an increasing number of critics and collectors over the years since they were first released.

For this new vinyl edition, Deutsche Grammophon decided to bundle all three records within a handsome, sturdy slipcase. I can understand some balking at the extra financial outlay involved if you want to buy just one or two of these records, but frankly it is worth the extra money to get all three, and the resulting price per album is lower than it would be if you were buying the records separately.

For this set, the slipcase box has disposable shrink wrap and OSS hype sticker (no Japanese-style outer sleeve). Each album contained within - identical in design and presentation to previous releases - is packaged without the usual resealable single-LP Japanese-style outer sleeve.

The one missed opportunity - and I think it’s a real shame DG didn’t spring for this - would have been to include within the slipcase some kind of simple insert with more background information on the conductor and these sessions. I think his status and the significance of this set warranted that extra inclusion.

(This reminds me to mention one of the other small criticisms I have about all the OSS releases. I would have loved each record to have included some more textual copy - as an insert, perhaps - placing the recordings within a historical and critical context, similar to what DG did with its series of CD reissues, The Originals. Maybe this is something DG could consider for future OSS releases…….)

William Steinberg was one of the most admired conductors of his generation, though his reputation has never attained the heights of his contemporaries. Something of a child prodigy, he was a highly accomplished violinist and pianist growing up in Germany, and won a conducting prize when he graduated from the Cologne Conservatory.

William Steinberg was one of the most admired conductors of his generation, though his reputation has never attained the heights of his contemporaries. Something of a child prodigy, he was a highly accomplished violinist and pianist growing up in Germany, and won a conducting prize when he graduated from the Cologne Conservatory.

With the rise of the Nazi party he eventually had to leave Germany and settled in Palestine, where, with the great Polish violinist, Bronislaw Huberman, he co-founded the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. The orchestra became an important home for the many professional Jewish musicians who had fled Europe, and eventually became the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. As Huberman said at the time:

"One has to build a fist against anti-Semitism—a first class orchestra will be this fist."

Huberman (l.), Toscanini (c.) and Steinberg (r.) with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Huberman (l.), Toscanini (c.) and Steinberg (r.) with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Eventually Steinberg moved to America after attracting the attention of Toscanini, for whom he had prepared the Palestine SO in a series of concerts. Toscanini hired him to be his assistant for the radio broadcasts of the NBC Symphony Orchestra. This was the beginning of a stellar career in the US, where Steinberg eventually conducted all the major orchestras, as he also did in Europe, particularly the London Philharmonic. He gained particular renown for his stewardship of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (1952 - 1976), turning that ensemble into an orchestra of the first rank.

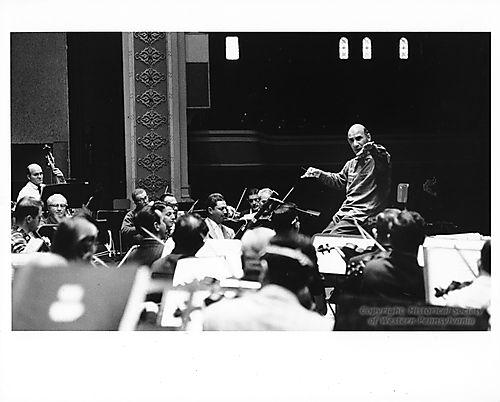

William Steinberg rehearsing the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

William Steinberg rehearsing the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

The recordings collected together in this box stem from the period between 1969 and 1972 when Steinberg was also Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a position he only gave up because of ill-health.

The long-time music critic of The New York Times, Harold C. Schoenberg - whose various books on composers, conductors and pianists are ideal guides for anyone getting to know the classical repertoire, as accessible as they are entertaining - had this to say of Steinberg when reviewing a 1964 concert: “His is a calm, logical beat, and he makes music in a calm, logical, well proportioned manner.”

Schoenberg continued to write that Steinberg’s interpretations were:

"… of a conductor ripe in experience, deeply immersed in the tradition of the score, responsive to the lyric elements of the music. Looking at his collected manner, one knows that nothing can ever go wrong. And nothing ever does.”

Steinberg’s obituary in The New York Times also had this to say:

Coupled with Mr. Steinberg's seriousness as a musician was an impish sense of humor. One of his associates described him as being “very humorous, always making jokes.” Principal guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic for two seasons from 1966 to 1968, he said of one part of the orchestra's audiences: “I love my little Friday afternoon ladies. With their cotton gloves the applause is not so loud; if they wore kid gloves I could hear them better.”

All of these qualities and more are on display in the recordings under consideration: Steinberg’s unaffected, detailed but straightforward approach to the music; his sense of humor (not taking himself or the music more seriously than warranted, an especially useful quality in the Strauss); his considerable gifts as an orchestra trainer (which inspired Toscanini to hire him).

Not for Steinberg the subjective emotionalism of a Furtwängler. Each of these recordings share the quality of an Old Master having layers of varnish removed. His Strauss is leagues away from the swooning Romanticism of a Karajan. The Holst (which Steinberg learned from scratch for this recording) is direct, forthright, with inner detail fully revealed - not something you can always say about other recordings. The Hindemith is likewise presented most engagingly without any fuss, with its glittering orchestration given full reign. All of these performances benefit from a sure rhythmic sense, with Steinberg eschewing any kind of spurious rallentando or accelerando. He keeps everything on a very even keel, letting the music speak for itself. For all these reasons, especially with regard to the Strauss and Holst, which have both been over-recorded to death and subjected to numerous conductor “interventions”, there is real freshness to the performances.

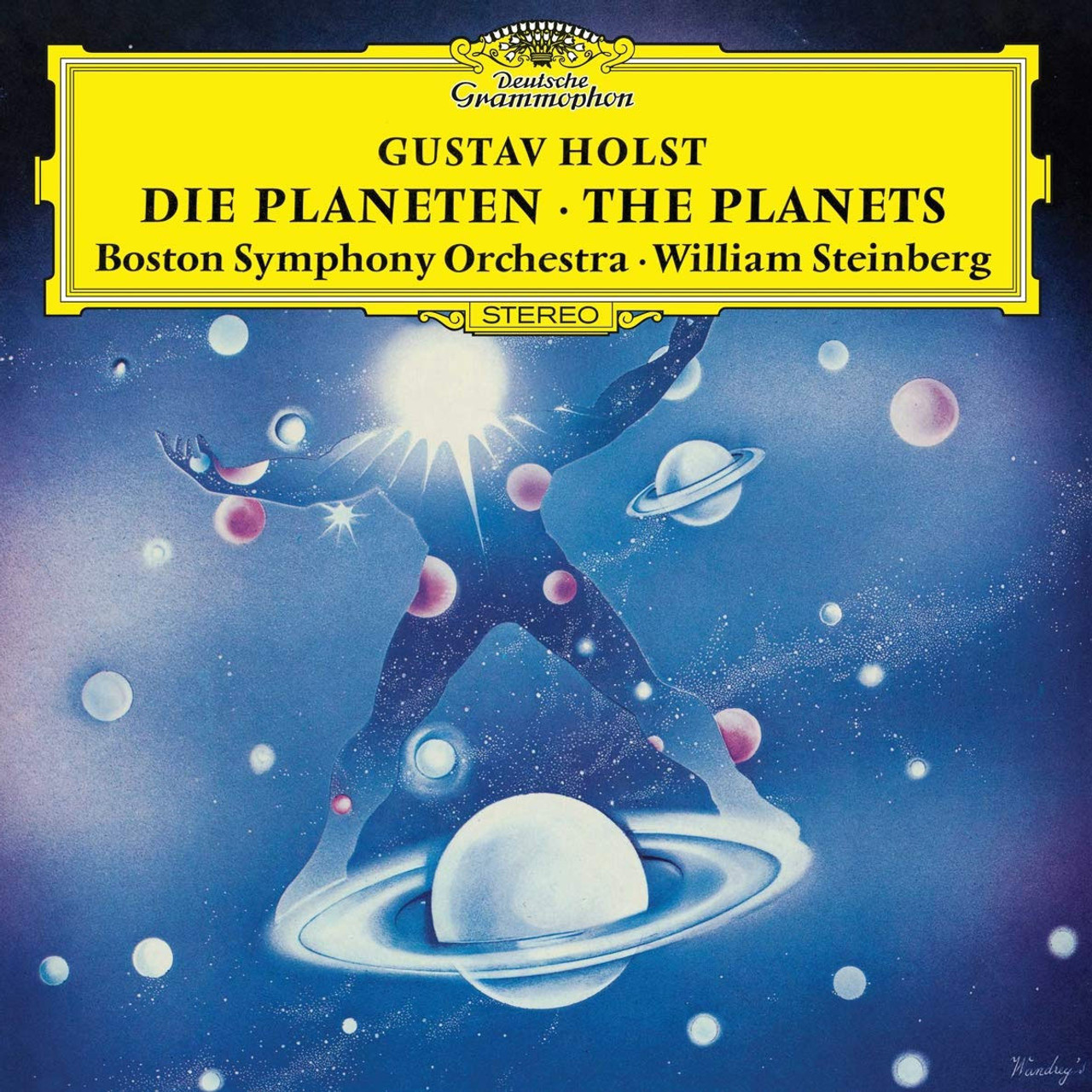

The distinctive, fresh artwork of Peter Wandrey (1939 - 2012) graced the covers of many classic DG recordings, including this one. He was also responsible for the striking cover of Steinberg and the BSO's Also Sprach Zarathustra included in the Steinberg box

The distinctive, fresh artwork of Peter Wandrey (1939 - 2012) graced the covers of many classic DG recordings, including this one. He was also responsible for the striking cover of Steinberg and the BSO's Also Sprach Zarathustra included in the Steinberg box

Gustav Holst: The Planets (Suite for Large Orchestra)

William Steinberg conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra and New England Conservatory Chorus (Director: Lorna Cooke de Varon)

Production: Karl Faust/Thomas Mowrey

Artistic Supervision: Rainer Brock

Recording Engineer: Günter Hermanns

Recorded September 9th and December 10th, 1970 in Boston Symphony Hall

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

Music: 10

Sound: 9

We have all gotten so used to hearing this work - especially the opening Mars movement - that it’s easy to forget just how original and, frankly, extraordinary it is. Holst had struggled to write a large-scale orchestral work for years, not being naturally attuned to traditional symphonic procedures. But with this suite, where each movement is a self-contained movement depicting the astrological character of each planet in the solar system, the composer was able to concentrate on short-form structure and pictorial effects.

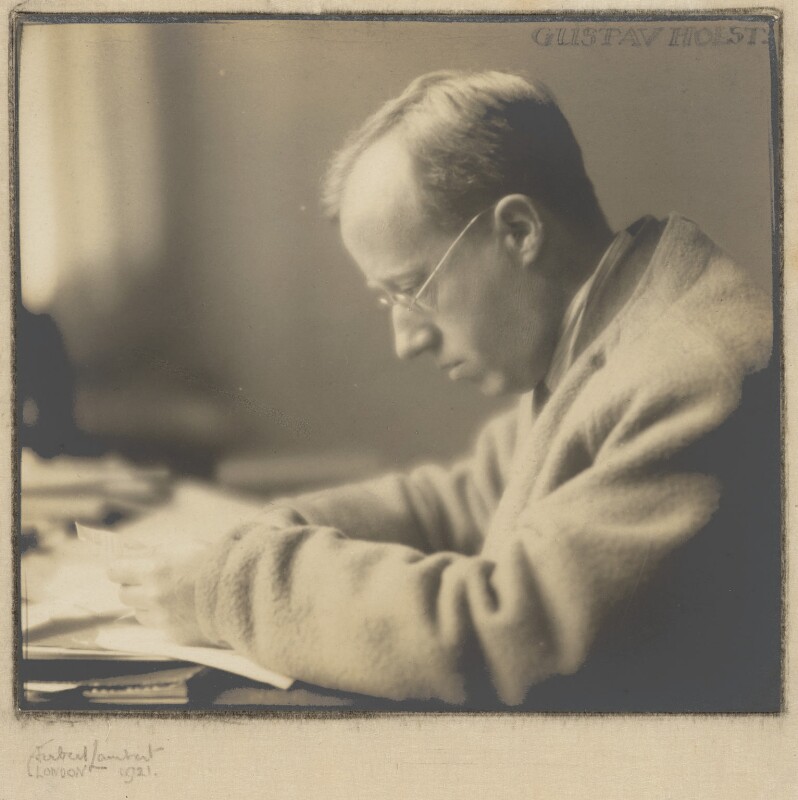

Gustav Holst (photo by Herbert Lambert, 1921, National Portrait Gallery)

Gustav Holst (photo by Herbert Lambert, 1921, National Portrait Gallery)

Holst was heavily inspired by his love of the early Stravinsky ballets, especially The Rite of Spring, with which The Planets shares a predilection for complex rhythmic patterns. The work is likewise a tour de force of imaginative orchestration; add to that a pervasiveness of melodic invention that few others can match. No wonder that, after an initially mixed reception, The Planets has become one of the most popular orchestral works in the entire repertoire, spawning a huge number of recordings, cover versions, and plain knock-offs. There’s the electronic Planets by Tomita; the various rock versions by Rick Wakeman and Jeff Wayne, and Emerson, Lake, and Powell; and numerous channellings of Mars in movie scores (eg. the opening scene of Gladiator).

In a familiar scenario we have seen play out amongst many creative artists, Holst himself became somewhat chagrined by the work’s popularity which thoroughly eclipsed his other compositions.

The Planets came into being in part because of the composer’s avid interest in astrology. Social functions chez Gustav would often involve the guests having their astrological chart read by their host.

It seems somewhat incredible to think now, but at the time this version was first released in 1971, Deutsche Grammophon lacked any recording of this most popular of orchestral extravaganzas in its catalogue. (As I mentioned above, Steinberg learned the work specially for these sessions). Part of the reason for this probably had to do with the fact that a lot of English music still wasn’t taken too seriously in mainland Europe. There was little or no Elgar or Britten in the DG catalogue (pace Lorin Maazel’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra from 1962), until Eugen Jochum recorded Elgar’s Enigma Variations with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1975, and Carlo Maria Giulini Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings and Les Illuminations with Robert Tear and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Philharmonia in 1979. There are still none of the major Vaughan Williams works in the DG catalogue, and little Britten (though one of the more unusual DG releases came out in the 90s, by the great Russian pianist Andrei Gavrilov, with the Vienna Boys Choir, performing some pretty rare Britten works; now available in an outstanding Eloquence box set of the pianist’s DG recordings).

I digress. When it came to The Planets, a sure-fire seller for any label that chose to record it, DG’s top star, Herbert von Karajan, had indeed recorded the work back in 1962, but that had been with the Vienna Philharmonic for Decca. It is still a highly regarded entry in the Planets sweepstakes.

It wasn’t until 1981 that Karajan committed his redo with Berlin for the Yellow Label to both CD and vinyl, using early digital technology, alas. This is an account that divides critics; I will confess to being in the minority that quite likes this rendition, despite the dodgy sound and some occasional lapses in ensemble and tuning. (I would love to see Esoteric or EBS tackle this one for SACD). At the time of its release, many remarked upon the ferocity and fast speed of Karajan’s remake of Mars, and in this he is very close to Steinberg’s rendition (Steinberg is faster and more closely miked). Both make sure you can really hear those famous opening string col legno “rat-a-tats” (col legion means playing the notes with the wooden side of the bow). This “must-hear” effect is often unaccountably all but inaudible on recordings, even on some of the most famous recordings.

It wasn’t until 1981 that Karajan committed his redo with Berlin for the Yellow Label to both CD and vinyl, using early digital technology, alas. This is an account that divides critics; I will confess to being in the minority that quite likes this rendition, despite the dodgy sound and some occasional lapses in ensemble and tuning. (I would love to see Esoteric or EBS tackle this one for SACD). At the time of its release, many remarked upon the ferocity and fast speed of Karajan’s remake of Mars, and in this he is very close to Steinberg’s rendition (Steinberg is faster and more closely miked). Both make sure you can really hear those famous opening string col legno “rat-a-tats” (col legion means playing the notes with the wooden side of the bow). This “must-hear” effect is often unaccountably all but inaudible on recordings, even on some of the most famous recordings.

And this brings me to an important and, given how many times this work has been recorded, rather unbelievable point. Which is that there is still no single recording, for me, that fully dots all the “Is” and crosses all the “Ts”, that fully captures all the facets, layers and depths of this truly remarkable work; no single recording that you can point to and say - “That’s the one!”

Every recording of The Planets that I’ve heard, even the great ones, have their blind spots, and I’m afraid Steinberg is no exception (he gets closer than many). It is one of the most challenging works to record, not just because it is scored for a huge orchestra (plus choir plus organ), but because that huge orchestra is used in such a huge variety of ways.

Mars, the Bringer of War may be perfectly paced (eg. André Previn and the LSO on EMI), but you don’t hear the texture of those opening col legno strings as much as you should. That EMI recording is balanced in such a way that the piece only makes its biggest impact in the massive climaxes later in the movement.

In Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity the fellow may be too serious by half: all rhythmic exactitude but no joy. Or everything may go great until the Big Tune (later reworked with text as the ultimate patriotic hymn, I Vow to Thee My Country) which is either too slow or too fast; or if that’s okay, the extraordinary coda when the Big Tune comes back amidst an extraordinary swirling musical view of the planet and its moons hurtling through the cosmos, is completely screwed up (musically and/or engineering-wise).

In Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age you simply may not hear - at all! - the ESSENTIAL tubular bells at the climax, chiming out the inexorable heavy tread of our mortality to bone-numbing, chilling effect. This one should curdle the blood. How the hell does this one get missed over and over again!

And in the final Neptune, the Mystic, those eerie, wordless women’s voices receding into the ether can be either far too present and correct, or too distant to start off with, or somewhere in between, or all of the above.

Don’t even get me started on how - on many recordings - you would be hard pressed to know there’s an organ there at all! (It’s there on the Steinberg, recorded at the same time as the orchestra rather than dubbed in afterwards, which makes a huge difference).

These are just some examples of the booby traps lurking on every page of this score for conductors, orchestras, and engineers alike. Even Sir Adrian Boult, who conducted the work’s first performance, and who committed the work to tape at least four or five times, does not have one definitive version.

So how do Steinberg and the BSO fare here? Pretty darn well, though with one reservation that I will get to.

William Steinberg conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood in 1969, the year he became Music Director

William Steinberg conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood in 1969, the year he became Music Director

Their Mars is less the inexorable march of massed Roman legions or the First World War’s grinding trench warfare (though let it be noted that WWI broke out after the composer had finished the movement’s sketches), more the Blitzkrieg of Hitler’s tank invasion of Poland and beyond. Steinberg’s Mars is relatively quick-footed, but no less relentless, ugly, inevitable, or merciless. It feels bang up-to-date, alas, fully in tune with modern warfare. And how thrilling to be able to really hear the “rat-a-tat” col legno strings at the opening.

In the two quieter movements that follow, the balm of Venus, the Bringer of Peace, and the quicksilver stylings of Mercury, the Winged Messenger, are all brought to life by the matchless wind section of the BSO at that time, and the fleet-of-foot and ever so sweet strings.

However, with the next movement, Jupiter, I started to wonder whether Steinberg’s leaning towards swifter speeds might be a problem. Jupiter is taken just a little too fast for this acoustic - so that the complex cross rhythms become a little jumbled. Also some of the majesty is lost. Saturn fares much better, and yes, those tubular bells fully register. However, Uranus, the Magician (my favorite movement) again gets a little muddy, and here, alas, I am going to have to talk about the one reservation I have about the recording: the reverberant acoustic. It’s a relatively minor quibble, but a quibble nonetheless.

We all know that one of the many reasons these OSS reissues have worked so well is the three-dimensional effect that has occurred from blending in the surround channels with the more direct stereo image. This has breathed air and space into recordings that previously felt hemmed in, constrained. On the OSS releases there is a sense of being enveloped by the music. Combined with what I have no hesitation in describing as the virtuoso cutting of Sidney C. Meyers, which has allowed more dynamic, spatial and timbral information into the grooves, the sound of these records reaches far into our listening rooms.

In my earlier review of the Ozawa Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique - recorded by the same orchestra in the same hall a few years later - I commented on what I thought was one of the most distinctive features of the new OSS remix/remaster: that I could hear deep into the detail of the music despite the fact that the orchestra was occupying a vast and very realistic acoustical space.

Here on The Planets I feel that balance has tipped just a little bit too far in the wrong direction, so that the acoustic sometimes overwhelms the orchestra. This is particularly noticeable in the louder movements, especially the ones with complex cross-rhythms, like Jupiter and Saturn; not so much Mars, where the rhythms are more straightforward and linear. The situation is further exacerbated by Steinberg’s quick speeds. The result is that the detail is sometimes obscured by the smudge of an over-resonant acoustic, to a degree that I found frustrating. This was not the case with similar passages (like the last two movements) in the Berlioz.

I shared my reservations with Rainer Maillard (who did not share them). I was keen to know a little bit more about the circumstances of the original recording and the new mix that might have contributed to what I was hearing. (I will also say that I found this over-resonant acoustic to be sometimes a problem on the Richard Strauss Zarathustra as well, though not on the Hindemith record).

I knew the orchestra had been placed within the body of the hall, not on the stage, for the recording sessions. (This had required removing all the audience stalls seating - a major undertaking). What I was very interested to learn was that the original recording team, with the very experienced Günter Hermanns as tonmeister, had been able to record the orchestra itself with a minimal number of mics; an approach which, historically, most people associate more with the early RCA Living Stereo, Everest, Mercury, and Decca recordings than with Deutsche Grammophon. (This, of course, might be an ill-informed assumption, partly deriving from the fact that those other labels were more open about this minimal miking and “purist” approach to their recordings, even using this as a selling-point in their marketing, whereas DG always emphasized its artists and repertoire over the technology used to record them).

In the interests of full disclosure, I communicated my reservations to Rainer Maillard at EBS so he would have an opportunity to respond to my criticisms, and maybe shed some light on the technical aspects of the original recording sessions, and the decisions he took in the remastering, that might have contributed to what I was hearing on the Holst and Strauss records. What he had to say is printed below.

Rainer Maillard:

“If you listen to the quadraphonic master tapes with four loudspeakers, yes, this hall sounds great on the masters and I am convinced it is exactly what the engineers tried to achieve.

“It is my responsibility to set the ratio for the mix-down. I would have been able to reduce the level of the room mics. But for me this wasn’t an option, because the sound does not get better this way. In the mix, you cannot reduce the amount of the reverb which is already on the tape and even on the front channels too.

“I really like the balance and I am convinced this is exactly what Steinberg and the team heard in the control room back in the day. I am convinced because:

1/ (Recording engineer) Günter Hermanns always used a similar ratio for front/back and I haven’t changed this ratio more than 1 dB.

2/ Listening to the front channels only on the master tapes you realize what Hermann’s intentions were. Normally I hear immediately his intention because if he struggled with the balance he often tried to over compensate with some spot mics. NOT with Strauss and Holst. These two records are amongst the few examples by Hermanns where he never over compensates. And the reason must be that he and Hans Weber must have liked what they heard coming out of the speakers. Again: I am quite sure they heard what you get on your LP.

“A few days ago when listening to both records at home, I really noticed (with pleasure) the sound of the timpani. (Something I would whole-heartedly agree with - MW) Often Hermanns put a spot mic on the timpani to bring it up in the mix. Not with Strauss/Holst. There is no spot mic on the timpani. But the sound of the timpani is clear - very clear although it is reverberant. Very clear although the location of the timpani is at the back of the hall. And only possible if you have a perfect room for the repertoire and a mic setup which fits perfectly.

“These recordings are for me a dream as a recording engineer: to get clarity (without using too many spot mics) in a big hall with a perfectly suitable acoustic (an acoustic which was shaped by the recording team by removing all the chairs).

“And this clarity stays even if the level gets high. Wonderful!!! Or in other words: on both these records you will find the highest amount of energy coming from the main mics only. In terms of the audiophile purist way, here we have an example for DG not to adopt the multi-miking philosophy.

“The sound of these Strauss/Holst come very close to what I would define as audiophile. Both recordings have the highest technical quality on tape of all the OSS releases so far. And I am convinced this box represents the intention of Steinberg and the recording team”.

I have quoted Maillard so fully here because I think it gives you real insight into both how he is thinking and how the original recording team were thinking.

(This also ventures into the fascinating realm of competing philosophies in the remixing, remastering, and “refreshing” of older recordings. Given the increasingly advanced technological tools engineers have at their disposal, the question arises: should you “fix” things you perceive as shortcomings on the original tapes, or do you intervene as little as possible. Clearly Maillard & co. are firmly wedded to the latter approach; others, whom I am sure we could all mention, not so much. I think it is so noteworthy that EBS have achieved the extraordinary feats of revitalization to be heard on the OSS releases via the older vinyl and analogue technologies, with nothing digital in sight).

Now some of you may be less bothered than I am by the large acoustic and the resulting reverberation on this (and the Strauss Also Sprach Zarathustra). It certainly is a problem in some movements more than others. For an example of the recorded sound quality on this record at its very best, I cannot think of a better example than Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age. But my misgivings on this point about the amount of hall reverberation (no additional reverb was added electronically then or now) have persisted through multiple listenings, and are the reasons my Sound rating is knocked down a point on both this record and the Strauss. (There are no such issues on the Hindemith record.)

Anyway, musically it is a fine reading of the work, with the BSO fully demonstrating their virtuosity. No wonder DG was crossing the pond so often to record them during this period. After hearing numerous versions of The Planets where conductors feel they have have to muck around with the score to justify yet another recording, Steinberg’s direct, unfussy approach is a breath of fresh air.

Will this be my go-to rendition on vinyl? Sometimes. As I mentioned above, there is no single version of this work that I’ve heard which supersedes all others. What was interesting was that when I went back to sample some of my other favorite Planets recordings for comparison, they often did not sound as good as I remembered them. Even with the problem (for me) of the over-reverberant acoustic, the Steinberg had somewhat spoiled me for some of my hitherto favorite recordings! (That was interesting and unexpected).

Most audiophiles will already have their favorites. Zubin Mehta’s 1971 rendition with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra on Decca/London has long been one of these, either on an original pressing, or the reissues by Speaker’s Corner and King Super Analogue Disc.

I must confess this is rarely one of my go-tos despite the fine sonics. I gravitate more to André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra from 1974 on EMI, a classic Christopher Parker/Christopher Bishop production. An original UK postage stamp pressing will suffice. The reissue on HiQ has more bass, but the vinyl will be noisier and need a lot of cleaning. My very best sounding version of this is the 2LP Japanese Toshiba pressing, cut at 33 and 1/3.

I must confess this is rarely one of my go-tos despite the fine sonics. I gravitate more to André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra from 1974 on EMI, a classic Christopher Parker/Christopher Bishop production. An original UK postage stamp pressing will suffice. The reissue on HiQ has more bass, but the vinyl will be noisier and need a lot of cleaning. My very best sounding version of this is the 2LP Japanese Toshiba pressing, cut at 33 and 1/3.

But in Previn’s Mars I really miss the closer perspective you get with Steinberg on those col legno strings at the opening; it’s missing on nearly all the recordings I’ve heard.

But in Previn’s Mars I really miss the closer perspective you get with Steinberg on those col legno strings at the opening; it’s missing on nearly all the recordings I’ve heard.

I also like both of Karajan’s versions. I know many will throw up their hands in horror that I even dare mention his later digital recording, but there is real freshness to the reading (together with some inaccuracies), plus some ravishing BPO playing. And his Mars is as fierce as Steinberg’s. Please, please, EBS or Esoteric, do an SACD remix/remaster of this (but in the meantime go for the Karajan Gold CD version for markedly improved sonics over the original vinyl or CD release).

I also dug out my early wide-band pressing of Karajan’s Decca VPO rendering, which is much better than you may remember, and it is characteristically atmospheric (though featuring some very odd “bells” in Saturn).

I also dug out my early wide-band pressing of Karajan’s Decca VPO rendering, which is much better than you may remember, and it is characteristically atmospheric (though featuring some very odd “bells” in Saturn).

Everyone should have at least one of the Adrian Boult versions in their library, and for me it’s a toss-up between his New Philharmonia recording from 1967, and his final 1979 version with the marvelous London Philharmonic, whose rich and ripe sonorities are perfect for this music; like the Previn, it’s a Parker/Bishop widescreen production. If pressed, I’d plump for this latter recording. Go for the original UK pressing.

Everyone should have at least one of the Adrian Boult versions in their library, and for me it’s a toss-up between his New Philharmonia recording from 1967, and his final 1979 version with the marvelous London Philharmonic, whose rich and ripe sonorities are perfect for this music; like the Previn, it’s a Parker/Bishop widescreen production. If pressed, I’d plump for this latter recording. Go for the original UK pressing.

Boult’s 1954 rendition on Nixa was the one by which I got to know the work, dancing around my room aged 4 or 5, and explaining all the action as I perceived it to any poor soul who happened to pass by. It was the one record above all else that got me wanting to learn a musical instrument. Check out the cool vintage artwork on the cover.

To be honest, several of my hitherto favorite Planets are on CD.

Andrew Davis’s 1994 version with the BBC Symphony Orchestra for Teldec, part of his superb series of recordings of English music, enjoys good engineering from the great Tony Faulkner, and it is one of the versions which, in performance terms, is the closest to getting everything right that I’ve heard. (I’ve not heard his later remake for Chandos as a dual-layer CD/SACD - reviews were mixed). I also really like the Hallé rendering on Hyperion conducted by Sir Mark Elder, which was the first to include the additional Pluto movement composed by Colin Matthews (a much better than expected supplement to the main work); this is again engineered well by Tony Faulkner.

Andrew Davis’s 1994 version with the BBC Symphony Orchestra for Teldec, part of his superb series of recordings of English music, enjoys good engineering from the great Tony Faulkner, and it is one of the versions which, in performance terms, is the closest to getting everything right that I’ve heard. (I’ve not heard his later remake for Chandos as a dual-layer CD/SACD - reviews were mixed). I also really like the Hallé rendering on Hyperion conducted by Sir Mark Elder, which was the first to include the additional Pluto movement composed by Colin Matthews (a much better than expected supplement to the main work); this is again engineered well by Tony Faulkner.

Others will swear by Charles Dutoit and the Montreal Symphony on Decca; Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic on EMI; Jurowski with the LPO on the orchestra's in-house label. The list goes on.... (feel free to list your favorites in the Comments section below).

Others will swear by Charles Dutoit and the Montreal Symphony on Decca; Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic on EMI; Jurowski with the LPO on the orchestra's in-house label. The list goes on.... (feel free to list your favorites in the Comments section below).

But sonically, put any of these side-by-side with the vinyl versions I have mentioned, including the Steinberg, and you are likely to be disappointed.

The original vinyl version of Steinberg's The Planets was always one of the better sounding DG records (and CDs). In this current sonic refurbishment for the Original Source Series I predict quite a few listeners will be tempted, like this writer, to channel their inner child and dance out Holst’s colorful, dramatic score when nobody’s looking…..

.png)