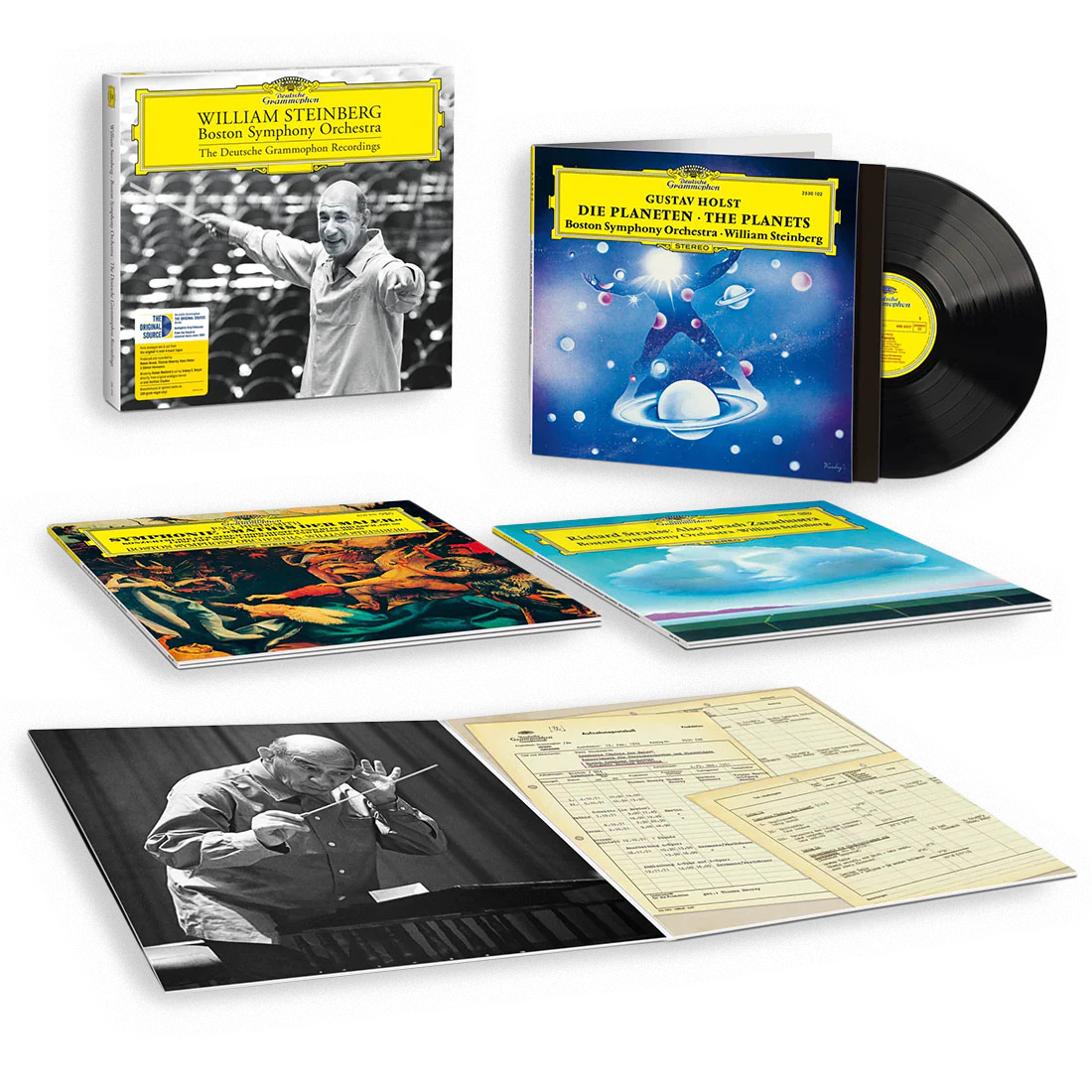

Classic Recordings by William Steinberg and the Boston Symphony Orchestra Are Reborn on Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Vinyl - PART 3: Paul Hindemith: “Mathis der Maler” Symphony and Concert Music for Brass and Strings

Emil Berliner Studios Revitalize DG catalogue gems for a new generation of listeners

Paul Hindemith in 1923

Paul Hindemith in 1923

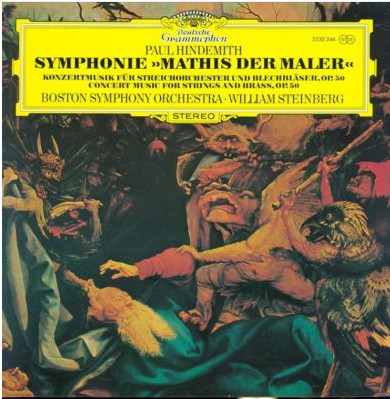

Paul Hindemith: Symphony “Mathis der Maler” (1934); Concert Music for Strings and Brass, op. 50 (1930)

William Steinberg conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Production and Artistic Supervision: Thomas Mowrey

Recording Engineer: Günter Hermanns

Recorded 4th and 5th October, 1972 in Boston Symphony Hall

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

Music: 11

Sound: 11

This is the record in the Steinberg box I was most looking forward to, and I was not disappointed.

Paul Hindemith is a massively underrated composer, and here we have two of his most recorded works in benchmark performances. I will confess that I had never heard these particular recordings before, but I was delighted from the moment I dropped the needle. The performances exhibit all the freshness and no-nonsense approach that make Steinberg’s Planets and Zarathustra so engaging, and they have none of the minor shortcomings in the sound I found with those two records.

Hindemith, born in 1895, is one of the most important German composers of the early to mid-20th century, but also one of the most unfamiliar. He came of musical age at a time when classical music was undergoing radical change at the hands of Stravinsky and Schoenberg. While some composers continued to work within the traditional diatonic tonal system, others followed Schoenberg’s lead and moved into atonality and, later, serialism.

Hindemith certainly began by composing in a more overtly late-Romantic, expressionistic idiom - like Schoenberg - but he eventually gravitated towards a leaner but still modern harmonic idiom, heavily influenced by the contrapuntal methods of Bach and Max Reger (1873 - 1916), and the Baroque style. Like Stravinsky in his adoption of the so-called neoclassical style, Hindemith turned to the music of the past to help him navigate the crisis in 20th century classical music. But it is important to note that while Stravinsky’s neoclassicism tips its hat to music predominantly of the Classical period (ie. Haydn, Mozart etc.), Hindemith is more rooted in the procedures of earlier Baroque and Renaissance music, and in particular the modal system of tonality which was prevalent during the Medieval period.

Hindemith with members of the Yale Collegium Musicum in New York in the early 1950s. All are playing early "period" instruments. From left to right, back row: recorders; front row: lute, bass and tenor viola da gamba

Hindemith with members of the Yale Collegium Musicum in New York in the early 1950s. All are playing early "period" instruments. From left to right, back row: recorders; front row: lute, bass and tenor viola da gamba

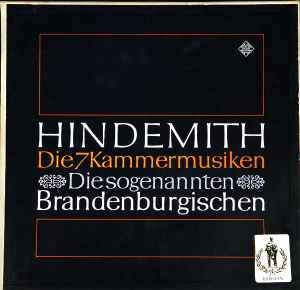

That Baroque idiom is most overtly referenced in Hindemith’s early group of works titled Kammermusik (“Chamber Music”). Composed between 1920 and 1927, these delightful mini-concerti are the modern equivalents of Bach’s six Brandenburg Concerti, and feature a range of solo instruments (including the unusual choice of the viola d’amore) set against a small chamber ensemble.

First recording of the complete Kammermusik by Hindemith on Telefunken (1969). Several future luminaries of the period instrument movement are amongst the players

First recording of the complete Kammermusik by Hindemith on Telefunken (1969). Several future luminaries of the period instrument movement are amongst the players

The Mathis der Maler Symphony was the precursor to Hindemith’s 1935 opera of the same name. The opera was based on the life of the German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald, an artist who retreated into his own work as a way of surviving the vicissitudes of the Peasants’ Rebellion (1524) and his own personal demons; he continued to paint within a more medieval idiom even as his contemporaries were adopting the more favored classical style of the time.

The subject matter was a perfect match for Hindemith’s music (and obviously resonated with the difficulties he confronted by working in 1930s Germany during the rise of the Nazi party). Hindemith had already started work on the opera when the great German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler asked him for a new orchestral piece he could take on tour with the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Symphony was premiered in 1934. Music from the Symphony was later integrated into the opera.

Throughout the Symphony, Hindemith quotes German folk melodies and chorales. Combined with his use of modal harmony, this gives the work a feeling of period authenticity, juxtaposed with Hindemith’s more modernist touches, and marvelously colorful use of the orchestra. As Hindemith himself is quoted in the sleeve notes: “Old folk songs, war songs of the Reformation period, and Gregorian chant were the nourishing foundation of the Mathis music”.

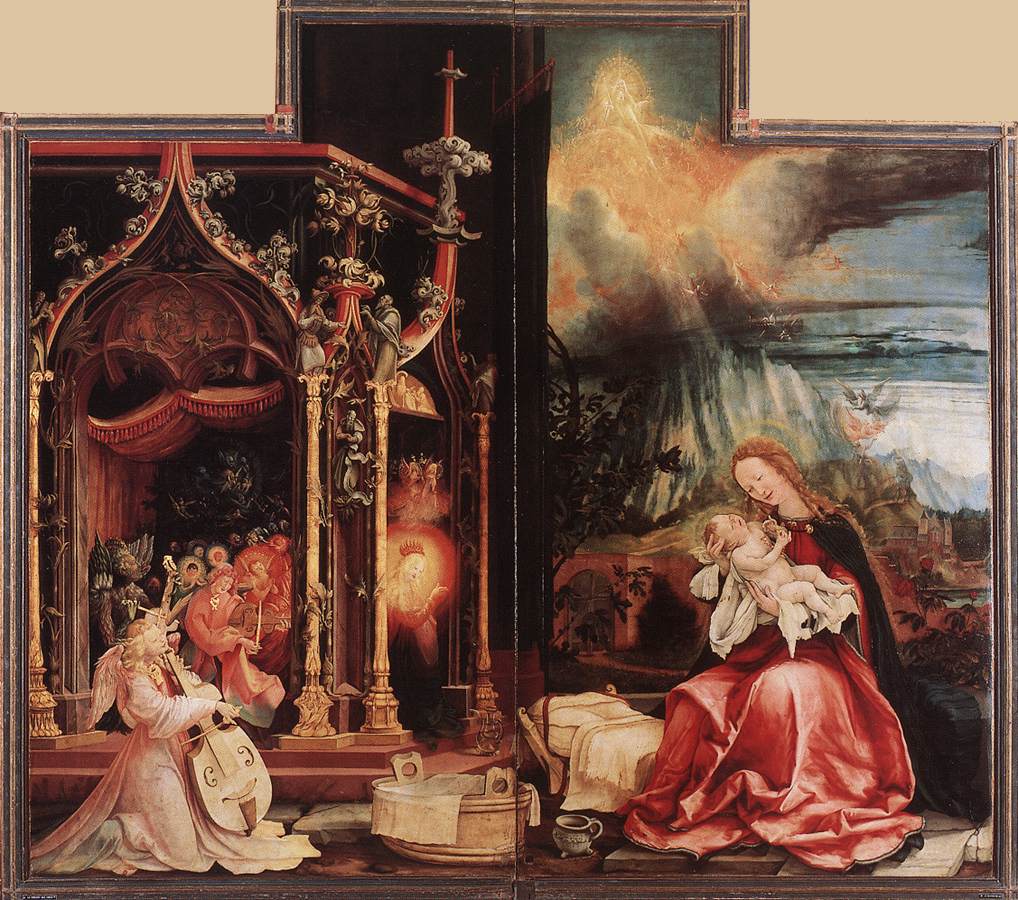

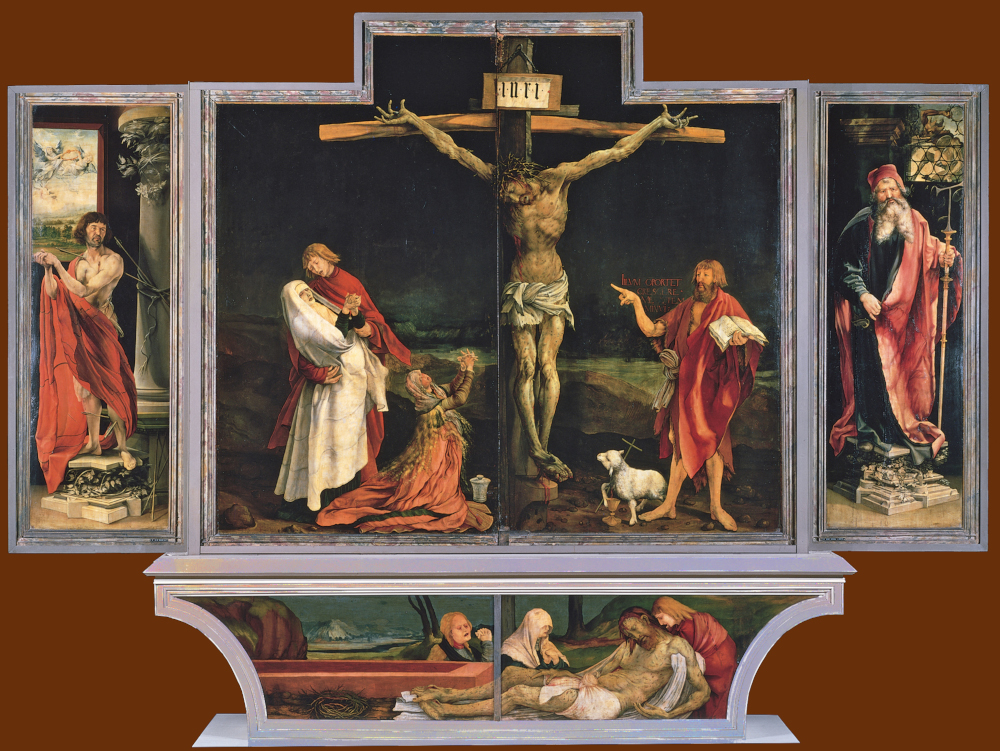

The three movements are each modeled on a panel from Grünewald’s masterpiece, the Isenheim Altarpiece.

The several layers of the Isenheim Altarpiece

The several layers of the Isenheim Altarpiece

The elaborate panels depict a series of biblical scenes. Hindemith's music relates to three separate panels.

Movement 1: Concert of the Angels

After a slow introduction, trombones play the melody “Es sungen drei Engel ein sussen Gesang” (“Three angels sang a sweet song”), while the rest of the orchestra offers increasingly complex counterpoint. This is a perfect musical equivalent to the angels depicted in the painting, conveying an appropriate sense of dignity and worship, and even hinting at the plangent tones of the viola da gamba played by one of them (albeit with the bow held incorrectly in an anatomically impossible position - better for the painting’s visual symmetry!).

.jpeg) The music then moves into a more conventional sonata-form movement which is highly reminiscent of the music of Michael Tippett at its most lyrical. There is such an atmosphere of happiness and rejoicing as the musicians serenade the Madonna and child, with the wind soloists of the BSO playing exquisitely throughout. I defy anyone not to feel their heart leap in the final apotheosis where the main tune returns set against mighty brass chords, chattering strings and wind doubled by glockenspiel flurries which sound like the Heavens rejoicing.

The music then moves into a more conventional sonata-form movement which is highly reminiscent of the music of Michael Tippett at its most lyrical. There is such an atmosphere of happiness and rejoicing as the musicians serenade the Madonna and child, with the wind soloists of the BSO playing exquisitely throughout. I defy anyone not to feel their heart leap in the final apotheosis where the main tune returns set against mighty brass chords, chattering strings and wind doubled by glockenspiel flurries which sound like the Heavens rejoicing.

This is glorious playing, caught in effortless sound that is as detailed as it is broad. A Concert of Angels indeed!

Movement 2: The Entombment of Christ

This is naturally more sombre, stark, with the orchestra broken down into isolated groups and solos. The music will have you thinking about similar passages in Shostakovich’s symphonies. Again, the exquisite solo wind and brass work of the BSO is shown off to great effect, and those always sweet strings weave their magic throughout.

This is naturally more sombre, stark, with the orchestra broken down into isolated groups and solos. The music will have you thinking about similar passages in Shostakovich’s symphonies. Again, the exquisite solo wind and brass work of the BSO is shown off to great effect, and those always sweet strings weave their magic throughout.

Movement 3: The Temptation of St. Anthony

_temptation-of-st.-antony.jpeg) The Temptation of St. Anthony is the right hand panel

The Temptation of St. Anthony is the right hand panel

The symphony’s most expansive movement progresses from a depiction of the Saint beset by foul creatures that could have stepped out of a Hieronymous Bosch painting (featured in enlarged detail on the album cover) to a triumphant victory over the dark night of the soul.

The two panels (reversed): Temptation is on left, St. Paul and St. Anthony on right

The two panels (reversed): Temptation is on left, St. Paul and St. Anthony on right

.

Temptation of St. Anthony - detail

Temptation of St. Anthony - detail

Again you are going to hear the mastery and unique voice of Hindemith’s music performed and recorded so compellingly that you will wonder why this work isn’t a regular on concert programs. Listen out for the exquisite strings-only passage about a third of the way through that offers pre-echoes of Bernard Herrmann’s strings-only score for Psycho. (Not surprising: throughout his conducting career Herrmann was a champion of 20th century music, and was already conducting Hindemith's music on the radio in the early 1940s). The final triumphant section is kicked off by the BSO’s matchless brass section, bright and burnished, binding together the rest of the orchestra. A fugue leads us into the finale which quotes “Lauda Sion Salvatorem” (“Praise the Saviour of Zion”). The final massive brass fanfares bind together the orchestral flurries of the piece’s triumphant end (which again had me thinking of film music - the conclusion to Walton’s score for Olivier’s Henry V).

The recording throughout is effortless, breathtaking, accommodating huge changes in volume while always capturing the nitty gritty details. And here the balance between the orchestra and the reverberation of the hall is perfect. I even detect a slight - and welcome - shift in the overall timbre of the orchestra from the earlier records in the Steinberg set. I wonder if different mics were used, or whether this is a by-product of slightly different placement of the orchestra in the hall, resulting in less reverberation and a slight shift in the orchestra’s overall tone as captured on tape. Whatever the reason, the orchestra sounds slightly warmer here than on the earlier Holst and Strauss recordings, closer to the sound on Ozawa’s spectacular rendering of the Symphonie Fantastique recorded in the same hall only a year later, released in the last OSS batch.

Side 2 brings us a work which was actually commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony to celebrate the orchestra’s fiftieth anniversary in 1931. I anticipate this being used by many a dealer at audiophile equipment shows to put their equipment through its paces. This is not as immediately appealing music as the Mathis Symphony, but no less impactful, especially sonically.

Here the DG engineers did a tremendous job capturing the divergent sonorities of the two instrumental groups. There is never a sense of one group crowding out the other, neither in the antiphonal sections, nor in the sections where they combine. The sound in this remastering is completely open, with seemingly infinite headroom, and as with the Mathis Symphony, there is none of that slight sense of too much room reverberation which afflicts The Planets and Zarathustra. Like Gundula Janowitz’s voice on the Strauss Four Last Songs, the brass emerge free and clear, dynamically taut, tonally true. The strings are caught in all their sweetness, but vital and present, holding their own against their brasher neighbours. The result is Hindemith’s music is presented in all its tonal and dynamic glory as well as I can possibly imagine it being presented, short of attending a live concert.

There are other great recordings of this repertoire out there, including Leonard Bernstein’s marvelous CD with the Israel Philharmonic that also includes the Symphonic Metamorphoses on Themes of Weber - a work that should be in everyone's collection.

I hadn’t listened to this in a while, but was pleasantly surprised by how good this early digital recording is, and how well the IPO is presented sonically (not always the case during this period of its recording history on DG). Bernstein was a lifetime champion of Hindemith’s music, and he is fabulous at capturing the jazzy rhythms that lurk everywhere in these works, especially the Metamorphoses. For Bernstein fans, this is an essential disc.

I hadn’t listened to this in a while, but was pleasantly surprised by how good this early digital recording is, and how well the IPO is presented sonically (not always the case during this period of its recording history on DG). Bernstein was a lifetime champion of Hindemith’s music, and he is fabulous at capturing the jazzy rhythms that lurk everywhere in these works, especially the Metamorphoses. For Bernstein fans, this is an essential disc.

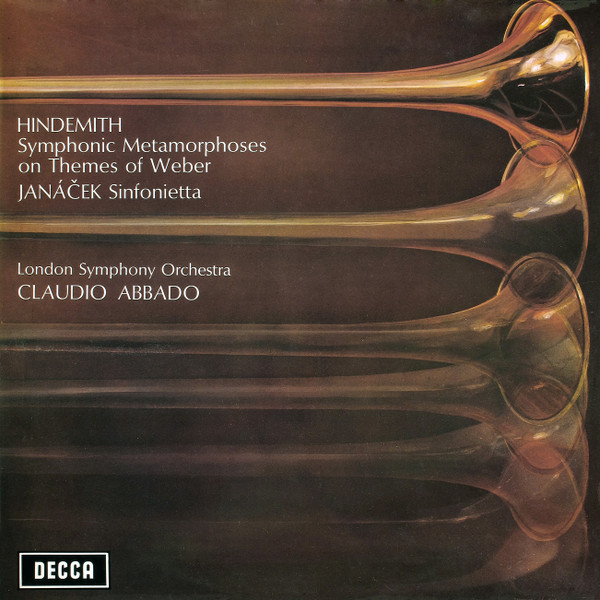

If you want to explore more of Hindemith’s work, vinyl lovers must, must start with Claudio Abbado and the LSO’s 1969 Decca record that couples the Symphonic Metamorphoses with Janacek’s Sinfonietta.

This was reissued by Speaker’s Corner, but later narrow-band pressings are readily findable. They will knock your socks off. Harder to find wide-band pressings add enough of that indefinable tube-mastered magic to be worth the higher cost of entry.

This was reissued by Speaker’s Corner, but later narrow-band pressings are readily findable. They will knock your socks off. Harder to find wide-band pressings add enough of that indefinable tube-mastered magic to be worth the higher cost of entry.

But for the Mathis Symphony, and the Concert Music for Brass and Strings, on vinyl, this new OSS pressing of Steinberg and the BSO is the only game in town. On every level - for its sound, playing, and the presentation of lesser known music that deserves to be far better known - this is an essential record for every classical music lover.

In conclusion, despite my reservations concerning what I feel to be occasionally over-reverberant sound on the Holst and Strauss, this Steinberg box is a mandatory purchase for the classical music collector.

Availability Issues

Even though the Steinberg box is sold out on the DG website, I am told it will be appearing for pre-order soon at the usual US outlets like Acoustic Sounds and Elusive Disc. So if you are interested in buying this, I would check in regularly. Unfortunately, I have been hearing a lot anecdotally (and via the usual on-line forums) about the difficulties of buying the DG Original Source Series.

Yes, you can buy all these releases from the DG shop, but that has become a very expensive proposition for anyone living outside of Europe. It’s also a problem if you end up with a defective LP - rare, but it does happen.

Since I am in touch with the folks at DG I have been able to communicate some of this frustration to the people who are in a position to help.

My sense is that the success of the series has somewhat wrong-footed everyone. I am thrilled that DG got those represses of the first batch of releases done, but now - ideally - they need to be more readily available from places other than the DG site.

As to the Steinberg box: I hope it will be repressed, or at least each of the records contained within it will be repressed and made available individually.

It’s a rare thing in today’s classical music market for classical titles to be in such high demand that they sell out within a month or two. A similar thing is happening with some of the more desirable mega-boxes that are being reissued (I hear the Ormandy Stereo Box on Sony is sold out already, after only a few months - repress please). The classical companies really have to figure this whole thing out. Classical music lovers are one of the few groups of music consumers who are still buying physical product regularly. The record companies need to make it as easy as possible for these customers to purchase that product. There does seem to be a real disconnect between different departments of these huge corporations that is making this situation much worse than it needs to be.

So please, please DG - try and get this all sorted out as we move into a new year of what I suspect will be more essential purchases for classical music lovers. We’re out there, and we are ready to spend our money on first-rate physical product like the Original Source Series!

The Future

I think it’s reasonable to say that the Original Source Series - in what has essentially been just six short months - has been an incredible success, in terms of its artistic merit, its sound quality, and its commercial viability. For those of us who have been collecting records for more decades than certainly I care to remember it has been a revelation. How thrilling is it that the many treasures lurking in the DG archive can find such radically new sonic life - in a sense be reborn - for new generations of listeners! And the fact that this has happened by going back to older technologies - analogue and vinyl - well that is just such a delicious irony and quite the delightful thing for us vinyl fans.

I don’t know the details, but I know more is on the way from the DG archives, and I can’t wait to see what new treats and discoveries lie in store.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again. I hope the relevant people at the other major classical labels like Decca/Philips, EMI/Warner, and Sony/RCA are paying close attention. If you take the time, money and effort to reissue your deep catalogue of titles on vinyl the right way - all-analogue with proper mastering and cutting engineers who really know what they’re doing - you will find there is an audience of very willing customers willing to pay extra for quality they can count on. Doing what DG has done is going to give you a source of amazing titles to re-release for decades to come.

In the meantime, while we wait impatiently for what comes next, just take a moment to send your thanks to the folks at Deutsche Grammophon and Emil Berliner Studios who made this all happen; and to those musicians and engineers back in the day who actually put all this musical treasure down on tape with such passion and technical know-how in the first place that their work can be revived over 50 years later sounding better than it ever has done before.

In an uncertain world I think that is some kind of miracle.

.png)