David Sylvian’s Massive ‘Do You Know Me Now?’ Box: Worth It?

Assessing the new, expensive, and near-complete CD set of Sylvian’s late career work

Every artist announces their end differently. Some make a big deal out of retiring, only to return three to five years later with an album or tour. Others creatively decline until they die, or until no one’s interested anymore. Or, they release their best album, slowly retreat from the spotlight, say that they’re “not currently thinking about a future in the arts,” make sporadic and seemingly random appearances on others’ experimental records, and reissue the entire catalog start to finish once all hope of new material has faded.

David Sylvian has done exactly the latter, but can we really complain? From fronting Japan, one of Britain’s biggest new wave groups, to his brilliantly arranged art pop solo LPs, to more left-field collaborations later on, Sylvian has seldom disappointed. Since Japan’s 1981 final studio LP Tin Drum (and their under-appreciated 1983 “live” album Oil On Canvas), he’s maintained a remarkable consistency with hardly any misses, despite his generally obtuse 21st century work alienating much of his original audience.

In 1999, Sylvian released Dead Bees On A Cake, his first proper solo LP in 12 years and a sprawling, painstakingly produced opus about love and spirituality. He was a family man who settled down with his wife and two daughters—and if the album is anything to go by—in peace.

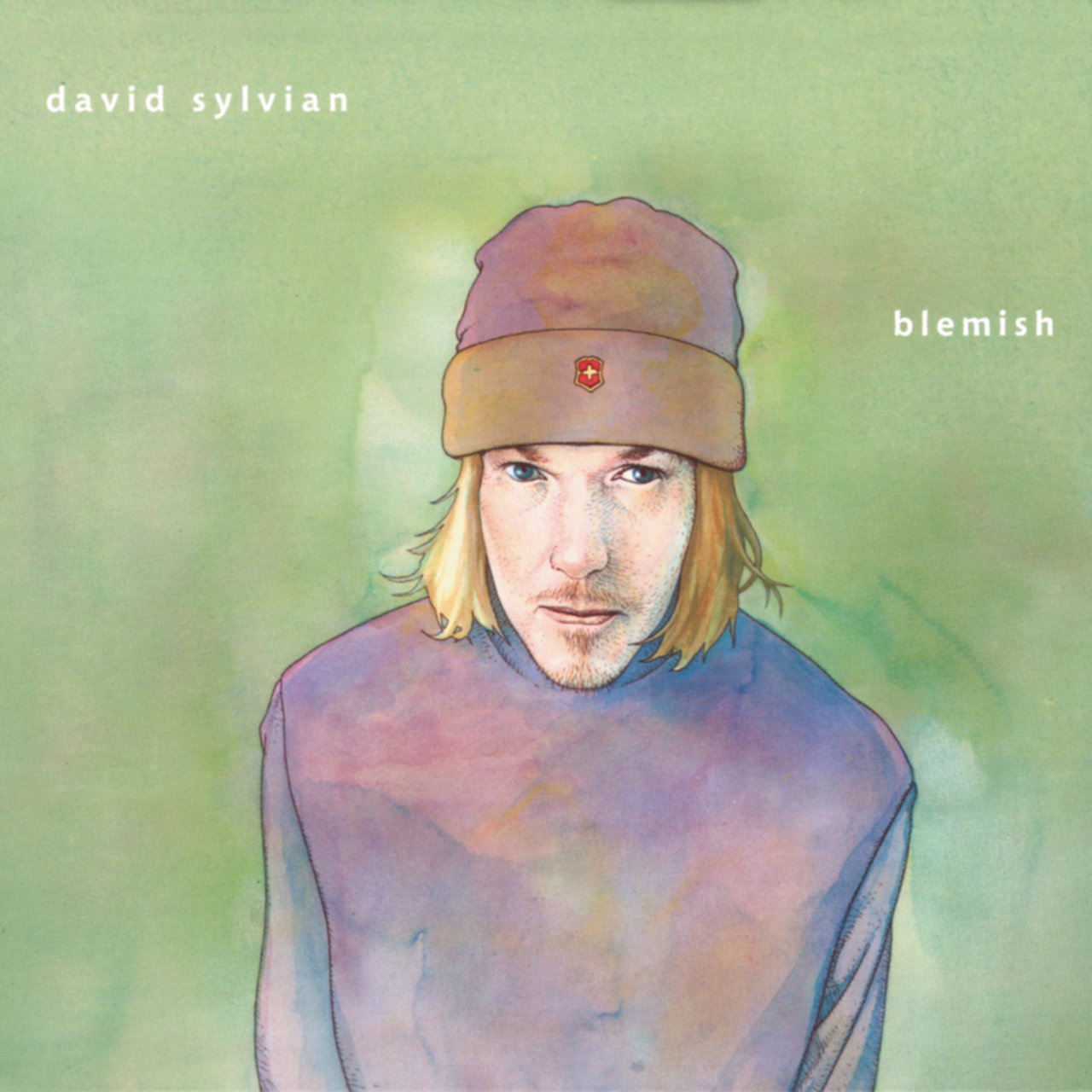

Shortly after, his contract with Virgin ended and his marriage collapsed. His next album, 2003’s Blemish, starkly departed from his 80s and 90s discography, and with that he established the Samadhisound label for his own releases and those by Derek Bailey, Harold Budd, and others. Now that he’s reissued his core catalog on vinyl, David Sylvian presents Do You Know Me Now?, an exhaustive 10CD box set containing his complete work on Samadhisound from 2003-2014. (It doesn’t even hint at, much less include, his two Grönland releases: the 2010 compilation Sleepwalkers and Stephan Mathieu’s 2013 Blemish rework, Wandermüde.) This webstore exclusive set retails for a whopping £144, or $187-188 depending on the exchange rate that day; you don’t get free shipping so for all intents and purposes, it’s $200. Still, I’m too much of a Sylvian fan to not buy it and review it even if there’s no new material and nothing's remastered. (Music scores are bolded at the end of each album or EP’s review; the entire CD set scores 8/10 for sound.) Here we go...

The Albums

With Blemish, David Sylvian headed towards the farthest frontiers of “pop” music, deconstructing it to its barest essentials in sound and structure. As recently as Dead Bees On A Cake, he sang with Bryan Ferry-like mannerisms atop often lush arrangements; one could even argue that Dead Bees gets too close to “adult contemporary” though it’s too artful and nuanced for such categorization. Here, Sylvian completely abandons all of that. The instrumentals are desolate soundscapes created by guitar pedals and other electronics. His voice remains rich but not as supple as a few years before, and his lyrics are some of his most minimal since “Ghosts,” Japan’s stark 1982 single that bizarrely became a UK top 5 hit.

With Blemish, David Sylvian headed towards the farthest frontiers of “pop” music, deconstructing it to its barest essentials in sound and structure. As recently as Dead Bees On A Cake, he sang with Bryan Ferry-like mannerisms atop often lush arrangements; one could even argue that Dead Bees gets too close to “adult contemporary” though it’s too artful and nuanced for such categorization. Here, Sylvian completely abandons all of that. The instrumentals are desolate soundscapes created by guitar pedals and other electronics. His voice remains rich but not as supple as a few years before, and his lyrics are some of his most minimal since “Ghosts,” Japan’s stark 1982 single that bizarrely became a UK top 5 hit.

That’s mostly because Sylvian’s songwriting approach drastically changed. While he previously wrote in a generally conventional fashion, here he ran already-recorded guitar improvisations through pedals, quickly wrote his lyrics and vocal melodies, and recorded however many takes necessary until he reached the final result. In the book that comes with this box set, he describes this method as “first thought, right thought.” He released Blemish as a download before distributors picked it up; with that, he launched Samadhisound.

Much of Sylvian’s later work centers around his divorce, and Blemish chronicles the immediate aftermath. The bareness is greatly effective. “And mine is an empty bed/She’s forgotten, I know,” he sings on the 14-minute opening track, his voice close-miked and at the front of the mix. “Late Night Shopping,” one of the album’s most structured moments, simultaneously sounds familiar and completely new, the perfect balance between his pop and experimental sensibilities. Songs like “The Good Son,” “The Only Daughter,” and the fragment “She Is Not” have loose narrative frames with inconclusive—and presumably dark—endings. It’s similar to (albeit less intense than) what Scott Walker did in his solo career; for that matter, Sylvian’s career arc from UK pop megastar to quieter solo artist to experimental hero closely mimics Walker. “The penny’s dropped/The room’s in order/I masked the spot/Me, the only daughter/Do us a favor, your one and only warning/Please be gone by morning,” Sylvian sings at the end of “The Only Daughter.”

In the context of what came after, Blemish remains very good though sounds like a transitional piece. Some “fans” complain that Blemish is just a guy whining about his divorce, but more egregiously that it’s not “real music.” I wonder what those people expect of Sylvian—an artist who famously disregards expectations and does his own thing—because Blemish still has core traits of his previous work. Those who truly dedicate themselves to Sylvian’s discography find great value in almost all of it, as it’s all from the same mind with his sharp melodic abilities and excellent curation of collaborators. While Sylvian previously worked with luminaries like Robert Fripp, Holger Czukay, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Jon Hassell (sometimes all on the same record), the only guests here are free improvisation guitarist Derek Bailey and electronic musician Christian Fennesz. Bailey contributes to “The Good Son,” “She Is Not,” and “How Little We Need To Be Happy,” his abstractions wonderfully contrasting with yet complementing Sylvian’s vocals. Fennesz builds a stronger soundscape on the defeated yet slightly optimistic closer “A Fire In The Forest,” by far the album’s most accessible moment and one of Sylvian’s most affecting songs ever.

That said, anyone who finds Blemish gratingly dull probably listened to the CD or download. I haven’t heard the (very expensive) original vinyl half-speed mastered by Miles Showell, but last year’s 180g reissue cut by Mike Hillier at Metropolis and pressed at Record Industry is excellent. The moment Sylvian starts singing, you’re immediately pulled in, and you’ll remain there for the LP’s 50-minute duration (the vinyl and Japanese CD have an instrumental bonus track, “Trauma,” that curiously isn’t anywhere in this supposedly complete $200 CD box set). He recorded Blemish by himself at his home studio, but listen to any of his other records and he clearly knows good sound. The electronics are slightly clearer on the CD, but the LP’s vocal richness and instrumental tangibility, especially on Derek Bailey’s guitar, seriously can’t be beat. If you’re even slightly interested, get a copy immediately. It’s not too expensive online, plays super quiet, has a decent package, and sounds better than 90% of other records I’ve heard. 8/10

Over the next two years, Sylvian recruited others to remix Blemish tracks and released the results as The Good Son vs The Only Daughter. There’s hardly anything to subtract from the originals, so the remix artists add more overt sonic structure. Unlike most remix albums, it’s generally very good; like most remix albums, however, it’s got hits and misses. Ryoji Ikeda’s haunting, string-laden rework of “The Only Daughter” is brilliant, but Readymade FC’s busy tinkling and cluttered percussion completely ruins “A Fire In The Forest” and doesn’t even rhythmically align with Sylvian’s vocal. Tatsuhiko Asano builds an off-kilter yet more accessible song around “How Little We Need To Be Happy”—one of the original album’s weaker moments—and while it’s not essential, Yoshihiro Hanno’s glitch pop remix of “The Good Son” makes interesting use of Derek Bailey’s guitar from the original. The remix album has a cohesive flow; I especially like the seamless transition between Burnt Friedman’s “Blemish” remix and Sweet Billy Pilgrim’s take on “The Heart Knows Better.” It’s mostly for hardcore Sylvian fans, though worth a shot for anyone who listened to Blemish and didn’t immediately love it. 7/10

Over the next two years, Sylvian recruited others to remix Blemish tracks and released the results as The Good Son vs The Only Daughter. There’s hardly anything to subtract from the originals, so the remix artists add more overt sonic structure. Unlike most remix albums, it’s generally very good; like most remix albums, however, it’s got hits and misses. Ryoji Ikeda’s haunting, string-laden rework of “The Only Daughter” is brilliant, but Readymade FC’s busy tinkling and cluttered percussion completely ruins “A Fire In The Forest” and doesn’t even rhythmically align with Sylvian’s vocal. Tatsuhiko Asano builds an off-kilter yet more accessible song around “How Little We Need To Be Happy”—one of the original album’s weaker moments—and while it’s not essential, Yoshihiro Hanno’s glitch pop remix of “The Good Son” makes interesting use of Derek Bailey’s guitar from the original. The remix album has a cohesive flow; I especially like the seamless transition between Burnt Friedman’s “Blemish” remix and Sweet Billy Pilgrim’s take on “The Heart Knows Better.” It’s mostly for hardcore Sylvian fans, though worth a shot for anyone who listened to Blemish and didn’t immediately love it. 7/10

Around the time of Blemish, Sylvian and his brother, Japan drummer Steve Jansen, started a project of more conventionally structured songs. Sylvian then combined it with a project he’d started with electronic artist Burnt Friedman, so the trio became Nine Horses. Their sole album, 2005’s Snow Borne Sorrow, is a mellow affair that, while more accessible than anything else in this box, takes a few listens to fully sink in. The songs still have the flowing, sometimes meandering nature of Blemish, yet the music is fuller, lusher ambient pop and Sylvian almost has the phrasing of a jazz singer.

Around the time of Blemish, Sylvian and his brother, Japan drummer Steve Jansen, started a project of more conventionally structured songs. Sylvian then combined it with a project he’d started with electronic artist Burnt Friedman, so the trio became Nine Horses. Their sole album, 2005’s Snow Borne Sorrow, is a mellow affair that, while more accessible than anything else in this box, takes a few listens to fully sink in. The songs still have the flowing, sometimes meandering nature of Blemish, yet the music is fuller, lusher ambient pop and Sylvian almost has the phrasing of a jazz singer.

If Blemish was the diary scrawlings and custody hearings, Snow Borne Sorrow is the post-divorce therapy sessions. Here, the lyrical perspective is one of acceptance, yet the meanings are more direct than any of David Sylvian’s other work. Never before or again did he write songs as overtly self-reflective as “A History Of Holes” (“When I was a boy/I saw through their lies/I swore I wouldn’t become/The thing I despised/But events overtake you”), or lines as individually sharp as “You drank all the water and you pissed yourself dry/Then you fell to your knees and proceeded to cry” on “Atom and Cell.” The songs’ lengths—only one of Snow Borne Sorrow’s nine tracks is under five minutes—and frequent lack of choruses allows Sylvian’s writing to spread out and indulge in such detailed continuity. His weary vocal performances are also among his best. (There are many aspects that make Sylvian’s music so great, and on the albums included here, he perfects each of them at different times.)

Musically, Snow Borne Sorrow is very textural. It sounds contemporary to 2005, but despite subtle touches of glitch pop and downtempo, it’s not forcing itself into any popular sound of that era. The acoustic and electronic elements blend seamlessly, the stylistic differences between Sylvian, Jansen, and Friedman making for a richly layered, intricately detailed sonic landscape. Those who heard Blemish and wished Sylvian would return to making “real music” presumably got their wish… but not for long.

Mysteriously, this has never been released on vinyl but really deserves a proper remaster. The CD is decent, albeit thicker, warmer, and louder than the rest of these albums. There’s some audible limiter distortion on the chorus of “Darkest Birds,” and the atmospheres are generally somewhat cloudy (possibly by design). Until that hypothetical vinyl reissue comes along, it’s worth getting the CD or streaming it. 8/10

Disc 4 of the box set collects EPs and non-album singles, mostly from the early-mid 2000s. The biggest takeaway is that Sylvian isn’t very good at making political songs. “World Citizen” with Ryuichi Sakamoto is a preachy alternative rock song about the sufferings of the world. It gets better the more you hear it, and I’d rather hear it from Sylvian than Bono, but he's not angry nor overly mournful, which limits its impact. The other version, subtitled “I Won’t Be Disappointed,” is bleaker (“your sense of purpose come undone”), the “I won’t be disappointed” refrain a perfect statement of resignation and hopelessness. It’s really a David Sylvian and Yellow Magic Orchestra collaboration with mangled credits, as Sketch Show (Yukihiro Takahashi and Haruomi Hosono) contribute ambient glitches reminiscent of their Tronika EP. Such a collaboration could never fulfill the unrealistically high expectations one would have for it, but at least it happened. Visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda also did an interesting, noisy remix of “World Citizen.” (World Citizen EP: 6/10)

Disc 4 of the box set collects EPs and non-album singles, mostly from the early-mid 2000s. The biggest takeaway is that Sylvian isn’t very good at making political songs. “World Citizen” with Ryuichi Sakamoto is a preachy alternative rock song about the sufferings of the world. It gets better the more you hear it, and I’d rather hear it from Sylvian than Bono, but he's not angry nor overly mournful, which limits its impact. The other version, subtitled “I Won’t Be Disappointed,” is bleaker (“your sense of purpose come undone”), the “I won’t be disappointed” refrain a perfect statement of resignation and hopelessness. It’s really a David Sylvian and Yellow Magic Orchestra collaboration with mangled credits, as Sketch Show (Yukihiro Takahashi and Haruomi Hosono) contribute ambient glitches reminiscent of their Tronika EP. Such a collaboration could never fulfill the unrealistically high expectations one would have for it, but at least it happened. Visual and sound artist Ryoji Ikeda also did an interesting, noisy remix of “World Citizen.” (World Citizen EP: 6/10)

The Money For All EP collects three Nine Horses outtakes and Burnt Friedman remixes of a few album tracks. Of the “new” songs, the title track is absolutely laughable. The anti-Republican sentiment is clear, but the words are too vague and Sylvian’s voice too mannered to effectively deliver lines like “Revolution, socialism/Read it in the rag/There’s a gun at your head/Put the money in the bag.” The first verse (“Wanna step on through?/Can I check that bag?/Is there something inside here/That could help you relax?”) sounds like he’s complaining about airport security; I feel his pain, but I’ve never liked the type of political song that tells you what’s right and wrong, no matter how much I agree with the message.

“Get The Hell Out” is another bitter and rather threatening song about his divorce. He did this better on “I’m Too Mad To Let You Know (Sign The Papers),” an unfinished demo from this era later released on his SoundCloud. A hook like “Sell the lot/Sign the papers” has no right to be as catchy as it is; it’s a shame he didn’t give those demos a proper release in this box set.

“Birds Sing For Their Lives” is a beautiful song sung solely by Swedish singer Stina Nordenstam, who has an amazing command of her unique voice. “Wonderful World” B-side “When Monday Comes Around” is another divorce song with an apathetic vocal performance from Sylvian. Friedman’s remixes of Snow Borne Sorrow tracks as well as “Money For All” and “Get The Hell Out” are interesting; fine, but not essential. After all of that, this CD features Sylvian’s last vocal single from 2013. More on that later. (Money For All EP: 7/10; “When Monday Comes Around”: 7/10)

In 2006, the Naoshima Futake Art Museum Foundation commissioned Sylvian to soundtrack an installation. A year later, he released it commercially as When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima, a 70-minute ambient piece layered with field recordings to bring the Honmura Village’s atmosphere—an essential part of the work—to the rest of the world. It’s great at filling up background space, but the vocal samples and bits of electroacoustic feedback aren’t enough for a fulfilling focused listen. It works best when paired with actual loud weather buffeting Naoshima, and I live an ocean away. Not bad for completists, though I don’t think it’ll interest anyone beyond Sylvian diehards or niche ambient nerds. 6/10

In 2006, the Naoshima Futake Art Museum Foundation commissioned Sylvian to soundtrack an installation. A year later, he released it commercially as When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima, a 70-minute ambient piece layered with field recordings to bring the Honmura Village’s atmosphere—an essential part of the work—to the rest of the world. It’s great at filling up background space, but the vocal samples and bits of electroacoustic feedback aren’t enough for a fulfilling focused listen. It works best when paired with actual loud weather buffeting Naoshima, and I live an ocean away. Not bad for completists, though I don’t think it’ll interest anyone beyond Sylvian diehards or niche ambient nerds. 6/10

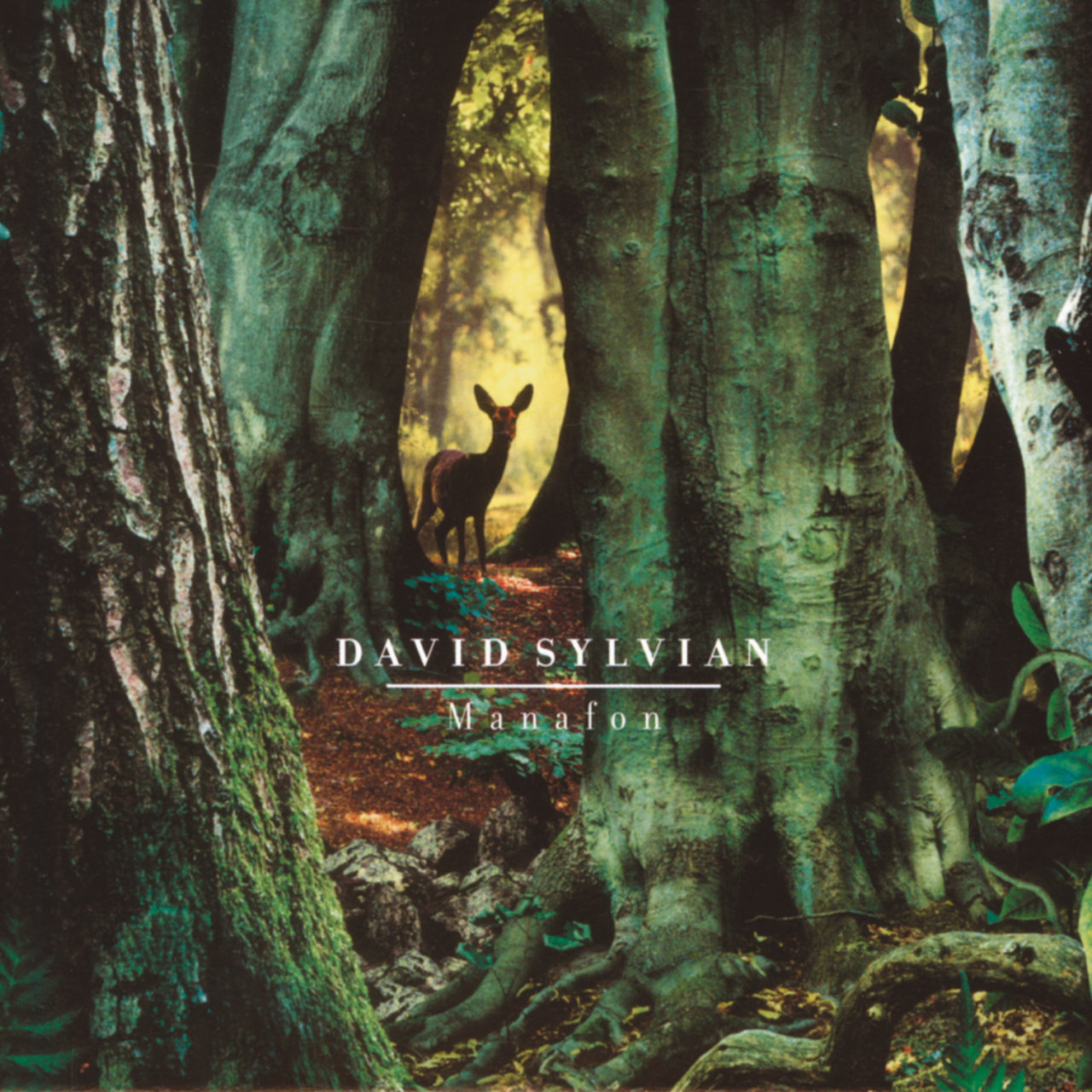

David Sylvian’s post-Japan discography has two absolute masterpieces: 1987’s Secrets Of The Beehive and 2009’s Manafon. (Both happen to be his best sounding albums too.) Beehive, a short ambient pop song cycle, bears an obvious Scott 3 influence; with lush string arrangements mostly by Sakamoto, it magically suspends time and space in its acquiescent melancholia. Manafon, named after the Welsh village where poet R.S. Thomas lived, is the polar opposite. It is desolate, unforgiving in its bleak minimalism. It throws you into the forest on the album cover, completely alone, forced to navigate life and death and all the complexities between, with almost nothing to guide you.

David Sylvian’s post-Japan discography has two absolute masterpieces: 1987’s Secrets Of The Beehive and 2009’s Manafon. (Both happen to be his best sounding albums too.) Beehive, a short ambient pop song cycle, bears an obvious Scott 3 influence; with lush string arrangements mostly by Sakamoto, it magically suspends time and space in its acquiescent melancholia. Manafon, named after the Welsh village where poet R.S. Thomas lived, is the polar opposite. It is desolate, unforgiving in its bleak minimalism. It throws you into the forest on the album cover, completely alone, forced to navigate life and death and all the complexities between, with almost nothing to guide you.

That is the entire point, and why Manafon is David Sylvian’s best album. Even if you love it upon first listen, you can’t grasp it immediately. Earthly as it is, its mysteries might never be solved. It’s the absolute conclusion of Sylvian’s work up to that point: first he stripped away the makeup and the glamor, then the romance, and now the spirituality, or any other comfort or illusion.

This extends to the musical arrangements, or lack thereof. Sylvian held group improvisations over a three-year span, then edited and built songs from them in a similar method to Blemish. Among the participants were Christian Fennesz, AMM’s Keith Rowe and John Tilbury, Evan Parker, Otomo Yoshihide, Sachiko M, and Toshimaru Nakamura. (Those who’ve dabbled in the world of EAI and similar genres might recognize the latter three from the 2004 Erstwhile release Good Morning, Good Night, a nearly two-hour album of sine waves, mixing board feedback, and vinyl surface noise. It’s possibly the most pretentious album I’ve ever heard, but I’m glad it exists and those high frequency sine waves are a great hearing test for older listeners.) Sylvian’s voice is by far the most stable rhythmic and melodic element, as the acoustic players pluck and hit their instruments and the electronic musicians produce sine waves, subtle synth drones, and sharp bursts of feedback and surface noise. The recording space and the frequent silence are as important as any other sound; it’s reductionism, after all.

On earlier records like his 1986 double album Gone To Earth, Sylvian noticeably dabbled in spirituality. By the time of Dead Bees On A Cake, he had a spiritual guru. But as evidenced on Manafon opener “Small Metal Gods,” it all betrayed him. “They’ve refused my prayers for the umpteenth time/So I’m evening up the score/Small metal gods/From a casting line/From a factory in Mumbai/Some manual laborer’s bread and butter/And a single-minded lie.”

The rest of Manafon is equally grim. “The Greatest Living Englishman” speaks of a man who dies by suicide after his life and work fail to amount to anything, “Random Acts Of Senseless Violence” deals with terrorism (“And it’s not just the boredom/It’s something endemic/It’s the fear of disorder/Stretched to its limits”), and “The Rabbit Skinner” describes “a man without qualities,” a “child of the 50s with no common sense and no easy resting place.” Some of these songs seem partly autobiographical, while others appear as relations to generational peers who lost their way. Even as an observer, Sylvian’s narrator is only occasionally a character in these stories. “Snow White In Appalachia” describes a disintegrating relationship with a woman addicted to drugs (“There were concerts and car crashes/There were kids she’d attended/And discreet indiscretions for which she’d once made amends”), the succeeding track “Emily Dickinson” saying of presumably the same character, “She was no longer a user/Don’t think she realized we knew that” as she becomes reclusive like Dickinson. These songs contain Sylvian’s most unvarnished lyrics: vivid and impactful, but letting you fill in the details.

Manafon is David Sylvian’s last proper vocal album to date. And it might forever stay like that, because can he really go much further than this? Unlike some of his experimental collaborators, his quality control is incredibly strict. One must have a pretty large ego to charge $200 for a 10CD box set in a rather standard package (more on that below), yet Sylvian is also the harshest critic of his own work. He refers to the perfectly cohesive Secrets Of The Beehive as unfinished and “something of a failure.” Manafon feels finished but its rawness suggests that maybe art is never exactly perfect or complete.

The CD sounds fine, but last year’s double LP reissue again cut by Mike Hillier and pressed at Record Industry will knock you over, even more than the Blemish LP. The vinyl itself is truly some of the quietest I’ve ever heard, and Sylvian’s voice emerges with startling realism. On the CD, the space is more congealed and the backgrounds aren’t as satisfyingly quiet. The vinyl edition is one of the top-tier recordings, musically and sonically. I can’t recommend it enough. 9/10

Old and new Sylvian merge on Died In The Wool—Manafon Variations, where Dai Fujikura puts string arrangements behind the original album’s vocal tracks. Jan Bang and Erik Honoré also contribute. These variations aren’t as good as the originals, but provide a worthwhile alternate perspective. The additional songs are the real gold. “I Should Not Dare” and “A Certain Slant Of Light” are Emily Dickinson poems beautifully set to music and sung by Sylvian, and his three original songs not on the original Manafon are lyrically similar and with richer arrangements. “The Last Days Of December” is especially essential. If Sylvian can bother to sing on something, it’s well worth my time to listen, as his vocal records hardly disappoint. Died In The Wool is no exception. 8/10

Old and new Sylvian merge on Died In The Wool—Manafon Variations, where Dai Fujikura puts string arrangements behind the original album’s vocal tracks. Jan Bang and Erik Honoré also contribute. These variations aren’t as good as the originals, but provide a worthwhile alternate perspective. The additional songs are the real gold. “I Should Not Dare” and “A Certain Slant Of Light” are Emily Dickinson poems beautifully set to music and sung by Sylvian, and his three original songs not on the original Manafon are lyrically similar and with richer arrangements. “The Last Days Of December” is especially essential. If Sylvian can bother to sing on something, it’s well worth my time to listen, as his vocal records hardly disappoint. Died In The Wool is no exception. 8/10

The second CD of the original Died In The Wool package, here presented as an entirely separate release, is an 18-minute track called “When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us.” Edited from a 50-minute instrumental piece by Sylvian and Fujikura commissioned for an installation on the Canary Islands, it’s a large-ensemble electroacoustic improvisation piece that, unless you’re an improv nerd, you’ll listen to once, appreciate its existence, regret spending money on it, and never touch it again. I wish he’d included the extended version considering how expensive this box set is, but 50 minutes of it would probably drive me up a wall. I’m sure it sounded great when these musicians recorded it, though I feel that this sort of music loses its power outside of a live performance. Sound-wise, it’s panoramic and vivid, likely because the edited CD is a stereo downmix from the full-length 5.1 installation mix. 6/10

The next CD in this box, 2012’s Uncommon Deities, also doesn’t translate very well to a recording playing through your home hi-fi. It’s not even a David Sylvian album, it’s Jan Bang and Erik Honoré featuring David Sylvian, Norwegian singer Sidsel Endresen, trumpeter Arve Henriksen, and a few more artists who don’t contribute enough to be listed on the front cover. It was originally made for Sylvian’s installation at Bang and Honoré’s Punkt festival. Sylvian doesn’t even sing; he’s reading poems by Paal-Helge Haugen and Nils Christian Moe-Repstad (translated from the original Norwegian) over soft, eerie backing by Bang, Honoré, and Henriksen (Endressen sings here and there).

Maybe the poetry is your thing. (An excerpt from “The God Of Adverbs”: “Of all gods he is the one closest to humankind […] The adverb is the part of speech pertaining to afterthought. When the adverb surfaces in human language, childhood is over.”). I’m not into it, but that’s besides the point. The reason why this doesn’t work resembles my grievance with “When We Return You Won’t Recognise Us.” Detached from a live or even installation context, it just sounds pretentious and annoying. It’s the sort of thing where you feel like you’re supposed to applaud after it’s all done, but clapping after a CD ends makes you feel like an idiot (though I was relieved when it was over), and neither the readings nor the musical bits are compelling enough. For some reason, Uncommon Deities is rather expensive on the secondary market (it's not on streaming). I suspect that demand is highest among the most deluded Sylvian fans or ardent readers of The Wire magazine. 5/10

Of the discs where David Sylvian doesn’t sing, the continuous, 64-minute There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight (2014) is by far the best one. Sylvian and Christian Fennesz (with additional contributions by John Tilbury) made beautiful, dark, and mysterious ambient music over which the late Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright read prose poems from his 2011 book Kindertotenwald. Wright died some months after its release but was pleased with the recording. He stumbles a bit (and Sylvian’s edits create further stutters), yet his reading is greatly moving because his words are thoughtful and his own. I’ll be sure to get the book, but There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight stands on its own as a disc worth returning to. (The original limited edition CD came in what seems like a stunning clothbound book of photos, but try finding one for a reasonable price. Even the “standard” digipak CD is expensive on its own.) 8/10

As of now, David Sylvian’s last vocal single was 2013’s “Do You Know Me Now?”/“Where’s Your Gravity?” included on Disc 4 of this box. (The last recording he sang on overall was “Sweet Paulownia Wood,” a reworking of Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto’s “Grains” included on last year’s Sakamoto tribute album To The Moon And Back. Sylvian’s added lyrics and vocals are about as good as anything on Manafon.) “Where’s Your Gravity?” is a cavernous, bass-driven piece with string arrangements dramatically creeping in and out. “Do You Know Me Now?” however, has a scarred finality to it; if it’s the last standalone David Sylvian release where he sings, then what a great way to end. His voice is a thin rasp, his words cryptic but symbolic: “And if you think you knew me then/Do you know me now?/I drew a child inside the womb/Justified myself/I stole the face of joy, the perfume of wealth/I atomized the boy within before he cut himself.” (It was first made for an installation by visual artist Phil Collins—no relation to the drummer—where musicians wrote songs based on phone conversations recorded in a homeless camp in Cologne.) Manafon stretched the limits of Sylvian’s work in form and ideology, while “Do You Know Me Now?” is additionally the conclusion of his different musical styles, like a haunted take on Secrets Of The Beehive. Whether or not it’s one of his best songs is subjective (I think it is), but it’s absolutely one of his most complete. (This is the first CD release with both of these songs. There was a limited 10” single that now commands high prices, and “Do You Know Me Now?” also appears on the 2022 vinyl reissue of Sleepwalkers.) 8/10

The Package

Most of the material worth having in the Do You Know Me Now? box set can be easily obtained separately and at a much lower cost. All of it sounds good, too. What about the package?

For $200, you expect a lot: a nicely illustrated hardcover book, solid liner notes, a nice box, maybe some marbles or rolling papers. You know, something. Do You Know Me Now? is a complete disappointment, an egregious ripoff if the Uncommon Deities and There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight CDs weren’t so expensive individually. And as someone who realized that I can blissfully live without the former, and who owns Blemish and Manafon on vinyl, I feel like I paid $200 for the Nine Horses album and the Franz Wright CD.

The box itself is a 10” slipcase that fits neatly with the recent John Lennon "Ultimate Mix" box sets, but it’s underwhelming for how little material it holds for the price. The three CD folders have nice paintings by Lance Austin Olsen, but they completely clash with Ruud van Empel’s bright photographs chosen for the box and 100-page hardcover book.

The box itself is a 10” slipcase that fits neatly with the recent John Lennon "Ultimate Mix" box sets, but it’s underwhelming for how little material it holds for the price. The three CD folders have nice paintings by Lance Austin Olsen, but they completely clash with Ruud van Empel’s bright photographs chosen for the box and 100-page hardcover book.

The book is utterly lazy. You get a short and pretty useless essay by Sylvian, an essay by graphic designer and writer Adrian Shaughnessy about the Samadhisound visual aesthetic, credits for everything, and some related artwork. Still, the album covers aren’t even properly shown, as they’re overlaid with the back covers that are faded out. Brilliant way to deface the artwork of your own albums.

Shaughnessy’s essay is one of the most embarrassing, pathetic things I’ve ever read anywhere. That is not the slightest exaggeration; it’s really that bad. He “writes” about “Sylvian’s superior grasp of visual aesthetics” and says:

“Just as his own records are the product of a surefooted instinct for choosing the right musicians to work with—he trawls the edge lands of the musical avant-garde to find players that bring added resonance to his music—so it is with the visual aspect of those releases that bear the legend: Art Direction by David Sylvian. Here too, he acts as a supercharged talent finder. He finds photographers, artists, illustrators, and designers to work with to create a discernible Sylvian visual aesthetic… Sylvian’s art direction credit is no vanity credit. He fulfills the role with vigor…”

Clearly, the supercharged talent finder David Sylvian has a surefooted instinct for choosing the right people to satisfy his ego. And he’s earned that ego by now, but charging $200 for a box set with your installation music, poetry readings, and that essay is a bit much. If Do You Know Me Now? cost $120, most of my complaints would vanish. $150, still acceptable. $200, however, is simply absurd for something of rather average quality. CDs can feel truly deluxe and special—look at any of those Japanese mini-LP packages with cool extras—except this package feels like the bare minimum: here, here’s a box with 10 CDs in it, have fun!

If you’re a Sylvian completist who doesn’t have much or any of this stuff, Do You Know Me Now? might be worth it. You might also listen to some of these discs and realize that having every last recording he ever made is completely unnecessary. If you’re swimming in a large pit of money and $200 feels like spare change, there are worse ways you could spend it. But even as a huge David Sylvian fan, I feel ripped off. If this had the same contents but higher quality—Japanese UHQCD pressings (the best sounding Red Book CD format I’ve heard), everything glossy and laminated, slightly better book design—it’d be fine. This is pretty mediocre. I recommend taking the $200 you’d spend on this box and buying the recent Blemish, Manafon, and Sleepwalkers vinyl reissues, a Snow Borne Sorrow CD, and having around $100 left to spend elsewhere.

.png)