Handel's "Messiah"—And The Recording That Changed The Classical Record Industry

’Tis the season, and in the classical music world that means Christmas carols, Nutcrackers, more carols—and Handel’s “Messiah”.

Which is actually quite odd, because Messiah was never intended by its composer as a Christmas piece - quite the opposite in fact. It was originally composed, in 1741, for performance at the most solemn time in the ecclesiastical calendar - Easter. The work tells the entirety of Christ’s story, culminating in His Crucifixion and Resurrection, with a meditation on the meaning of His life and death to Christians. So, this is hardly the stuff of Christmas levity.

However, the first part of the oratorio is such a vivid, dramatic, and tuneful representation of Christ’s Nativity, and the hope embodied therein, that it is hardly surprising it has been absorbed into the canon of Christmas music. Many church choirs and smaller choral societies might perform just this opening section of the work (with the Hallelujah chorus thrown in for good measure) at Christmas time, while Messiah has such a universal familiarity that performances of the whole work, as well as Sing-A-Long Messiahs, are as ubiquitous a ritual throughout the holiday season as any Sing-A-Long Sound of Music or Frozen in the secular realm.

All of this is a good a reason as any to talk about this lynchpin of the Western classical music tradition, especially at this time of year. But for anyone who loves classical music or collects records there is another reason to talk about Messiah, and that is the special recording issued in 1980 by Decca’s early music imprint, L’Oiseau-Lyre: a recording which changed the classical record industry in ways that are still with us some 40 years later. Appearing in a beautiful 3-LP box set, with a William Hogarth painting of Christ’s Ascension (1756) set amid the now standardized white frame and ornate border of all L’Oiseau-Lyre releases, Christopher Hogwood directed the Academy of Ancient Music and the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, with a team of largely unknown young soloists, in a recording that was so fresh and exciting - and sounded so different from all previous recordings—that it was as if two centuries’ worth of heavy varnish and dust had been peeled away from an Old Master artwork (an analogy that Hogwood himself liked to use).

It is rare for a single classical recording of any work or artist to have as seismic an effect on the industry it represents as this set did. In later times you might point to the phenomenal success of the Three Tenors concert as a case where a classical recording rivaled the Beatles or Michael Jackson as a sales juggernaut. But for a 3-LP set of a 200-plus year-old oratorio to be such an enormous critical and sales success, and in the process to redefine the course of the classical record industry? Well, that is remarkable, and worth talking about.

The Classical Market State of Play

By the end of the 1970s the classical market was saturated with multiple recordings of standard repertoire, by which I mean the Western canon from Bach through to Stravinsky. Most collectors would have multiple copies of a favorite work on their shelves. Unlike the jazz and pop markets which were all about recording the latest singers and bands, the classical market relied on big name conductors, soloists and orchestras to provide their own distinctive “take” on a work—and to cover the bottom-line financially. Catering to many listeners' need for a reliable guide through this sometimes bewildering array of new and reissued older recordings there appeared magazines of comparative record reviews and features, of which the most famous was the UK’s Gramophone, founded by Compton MacKenzie in 1923, and still published monthly today. (In the US, Fanfare magazine, founded in 1977 and still published today, offered a refreshingly different prospective on new releases).

Certainly, there was a continuing drive to record more obscure corners of the repertoire, but these records were more the province of specialty labels, or essentially tax write-offs for the majors. So, while, for example, Deutsche Grammophon would lead its portfolio with its superstars like conductor Herbert von Karajan, it also made a point of recording difficult avant-gardists like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Toru Takemitsu.

By the end of the 1970s classical records of standard repertoire were beginning to sound similar. A unanimity of instrumental, orchestral and vocal timbre had settled upon over two centuries of music, with apparently little thought given to whether that sound was serving such different music of different eras and different aesthetic purposes to equal effect. The distinctive timbres of different nations’ orchestras, beautifully captured on records from the 50s and 60s, were rapidly devolving into the modern, corporate orchestral sound. A generalization, of course, but largely true for where we find ourselves in 2022. For sure, modern, contemporary music of the second half of the 20th century was embracing electronics, harmonic dissonance and rhythmic iconoclasm - but who was listening beyond the avant-garde fan boys?

For an industry built on the idea that every new recording of a familiar work was that it would sound different, by virtue of the performance, or the instruments, or the recording quality itself, this was quite the potential problem, and record executives knew it.

What no one could have foreseen was that rescue came in the form of an eclectic group of obsessive practitioners and, frankly, music nerds from the groves of academia; PhD students and professors who decided instead of writing papers about centuries-old instruments and performance manifestos, would actually dust off those same instruments sitting unplayed in museums (or get someone to make modern copies that didn’t keep breaking down), start playing them, and put academic theories into performance practice.

And then record the results.

For better or worse, what followed gave the classical industry a much-needed infusion of fresh blood, and the results have not only given collectors reasons to buy the same music yet again—and again—but have also revolutionized how we think of and perform music of the pre-Classical era right up to the early 20th century music, as recent releases of Mahler and Debussy on “period instruments” demonstrate.

And standing proudly at the Big-Bang moment of the HIP (Historically Informed Practice) and/or Period Performance/Instrument Universe is Hogwood’s 1980 recording of Handel’s Messiah: the set that by virtue of its unqualified artistic success and massive sales figures launched a 40-plus years (and counting) revolution in how we think about and perform classical music.

“If we build them (the instruments), they will come…..”

This was always the biggest challenge—the instruments themselves. Finding ones that worked, or building ones that worked—and sounded decent—and figuring out how to play them, preferably in tune. In other words, just covering the basics.

None of that was as easy as it sounds. Instrument makers like Arnold Dolmetsch (1858-1940) set up shop to make harpsichords and recorders., then branched out into viols and lutes. As a kid in the 60s I, like many others, was handed a plastic Dolmetsch recorder in school and taught how to read music. There we all were, 7 and 8 year-olds, playing various ditties in massed recorder choirs!. (As my own interest in early music developed, I graduated to bespoke wooden Dolmetsch instruments and a viola da gamba, and studied with Arnold’s son Carl and his grandchildren, Jeanne and Marguerite).

To understand the way period instruments differ from modern ones, let’s consider members of the string family—violins, violas, ‘cellos, double-basses—the core of the symphony orchestra.

The string instruments played in Bach and Handel’s time may have looked similar to their modern counterparts, but they were physically different in small but crucial ways. They all used gut strings. Gut strings go out of tune very easily. They also snap easily. So, as music became more demanding, as orchestras grew in size moving into the 19th century Romantic era, and string instruments had to compete with more and more brass and woodwind—let alone percussion—players began to use metal strings, or gut strings entwined by metal, which were less prone to go out of tune and had more projecting power. The trade-off was that the string sound became more silvery, more cutting, less round and woody. Vibrato—the technique where a player rolls his finger stopping the string on the fingerboard at high speed, to give a note more intensity—went from being a technique used sparingly, more as an ornament to the sound, to being THE sound, again to help the strings cut through the other orchestral layers. As composers extended the range of notes required in their music, the fingerboard became longer too.

Violinists began to have chin rests added to the bottom of the violin body to make the instrument not just more comfortable to hold but to provide the player with more purchase as he applies weight to the bow. The bow changed too, and how you held it. In the Baroque and earlier periods, the bow was shorter and was held not at the end, where the frog joins the horsehair to the wooden frame, but several inches higher. Again, the change in the bow position was to help the player bring more weight and heft to his bowing arm, making it easier to tackle the more intricate lines composers were writing for the instrument. Finally, smaller devices to aid in micro-tuning strings were added where the strings joined the tail rest.

Examining the differences between Baroque and modern violins

While all these changes to the violin’s structure made perfect sense in the context of turbo-charging the instrument to play the heavier romantic repertoire of Berlioz and Brahms, they all cut down on the natural resonance of the instrument, the ability of the strings to more freely resonate with the wood body of the instrument, and for the bow to be applied more fleetingly. A lighter, shorter bow aids the player in executing fast runs of notes, intricate ornamentation, or in creating contrasts between notes allowed to resonate without vibrato versus notes where vibrato adds subtle shades of color and intensity. The Baroque string instrument was all about letting the instrument “sound” as is, as opposed to imposing a sound on it. Not that one is better than the other, but the music written with this Baroque instrument in mind necessarily played to that instrument’s strengths. Trying to work backwards to that sound via a modernized instrument would only take you so far.

Which was the essence of what the HIP/period instrument crowd were trying to achieve. They argued that by going back to the instruments the music was actually written for would immediately open up a way of playing the music that was more organic, closer to its original execution. And in doing so you would reveal some of the essence of the music that had been lost, as well as making it easier to play, and therefore less effortful in its affect.

Not that the brass and wind players would share with their compatriots that sense of the instrument being “easier” to play. Creating several octaves’ worth of notes from a metal or wooden tube using just your lips and mouth pressure is fiendishly difficult, and the various mechanical devices added to brass and wind instruments during the 18th and 19th centuries actually made players’ lives much easier. Going back to the instruments’ Baroque and Renaissance forbears required players to produce nearly all their notes using lips alone. One of the vicarious thrills of listening to earlier HIP recordings is to hear just how close to disaster the brass players in particular regularly come.

Anyway, as period instrument practitioners began to proliferate, the record companies set up sub-labels to cater to this new repertoire. Deutsche Grammophon established the Archiv label in the 50s with its own distinctive beige, later silver, design, incorporating extensive scholarly notes. In case you were in any doubt, the design made no pretense at conveying the idea the record contained within was an accessible, commercial product: an Archiv release was the record as textbook. Decca’s early music imprint L’Oiseau-Lyre actually started out as a French publishing company in the 1930s, then started issuing records in the 60s, becoming fully owned by Decca in the 1970s. Decca also had a partnership with Teldec/Telefunken in Germany, setting up in 1958 the imprint Das Alte Werk. This is where Nicolas Harnoncourt began his landmark project to record all of Bach’s cantatas on period instruments in the 60s.

HIP recordings of the 50s and 60s of baroque repertoire were largely performed on modern instruments but with smaller forces and an awareness of period style and ornamentation, with a harpsichord thrown into the instrumental mix. Prime examples of this approach were the hugely successful recordings by Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields on Decca/Argo, I Musici on Philips, and Karl Richter ’s Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra on DG’s Archiv label. It was only in Renaissance music and earlier that the more exotic instruments of the time, or at least modern copies, were recorded. And it was within this realm that the first bona-fide star of the period instrument movement emerged—David Munrow.

The Pied Pipers of Early Music

David Munrow embodied the essence of that quintessential British type—the amateur professional. His preternatural enthusiasm and musical abilities just seemed to appear—in High School he taught himself to play the bassoon in two weeks. While studying for a Master’s degree in English at Cambridge he became more and more involved in the performance of early music on the instruments it was written for—he was a virtuoso recorder player—and, together with Christopher Hogwood, another performing academic, formed the Early Music Consort of London in 1967. Through a series of stunning records and box sets for EMI and later Deutsche Grammophon, Munrow brought to life music of the Renaissance and earlier for an audience eager for fresh sounds and musical illumination. The BBC took notice, and created a radio program for children called Pied Piper on which Munrow, and sometimes Hogwood, would find inventive ways to engage young minds in the discovery of music. It was the British equivalent of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts, and created lifelong music enthusiasts out of millions of youngsters (and adults).

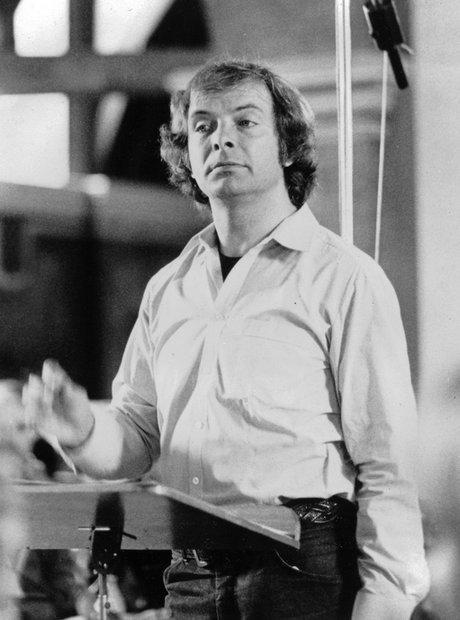

After Munrow died at a tragically early age, Hogwood, who had already independently formed the Academy of Ancient Music in 1973 for the performance of Baroque and Classical era music on period instruments, took up the mantle of the HIP/period instrument movement in Britain. Like Munrow, Hogwood was above all a communicator, someone who wore his deep musicological knowledge lightly as he engaged audiences and musicians with the thrill of new discovery. Signing a record contract with Decca’s L’Oiseau-Lyre early music imprint, he began a series of recordings that were to completely reshape how musicians and audiences thought about not just “early music”, but all music.

Christopher Hogwood

Christopher Hogwood

Reimagining Handel and Messiah

By the time it was decided to record Handel’s oratorio in 1979, Hogwood and the AAM had already released several successful records, and Peter Wadland, the label’s new visionary director, realized he had musical and commercial gold on his hands. He did not hesitate to greenlight several ambitious, multi-year projects, including the recording of all of Mozart’s symphonies in collaboration with Dutch virtuoso baroque violinist, Jaap Schroder, who was to become concertmaster of the AAM.

But recording Messiah represented a significant statement of intent, both for the label and Hogwood. It was a core work of the classical repertoire, with scores of well-admired recordings already out on the record shelves. Everyone already had their favorites, be it Thomas Beecham’s beloved 1959 “re-orchestration” of the work for RCA, or Sir Colin Davis’s 1966 rendition for Philips, still with a larger choir and traditional, “big-voiced” soloists, but with an awareness of the new scholarship and therefore featuring lighter textures and faster speeds. In 1977 Hogwood had even prepared the performing edition for another recording that broke new ground by focusing on a particular performance by Handel in 1743, with Neville Marriner conducting the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.

G.F. Handel (1756, Thomas Hudson)

G.F. Handel (1756, Thomas Hudson)

Handel was a particular specialty of Hogwood’s. Throughout his career he returned again and again to the composer, and he had a natural affinity for the composer’s idiom (an empathy he did not share with Bach to the same degree). On the surface, Handel seems less complex than Bach: a composer of good tunes conveyed with straightforward harmony and rhythmic vitality. Not for him Bach’s endless contrapuntal complexity, although Handel was perfectly capable of writing a masterly fugue, that musical form that represents the apex of compositional technique. Handel always seemed a natural fit with Hogwood’s temperament: warm, outgoing and enthusiastic, wearing his considerable abilities lightly, just wanting to share in his joy for the music.

I worked extensively with Chris in Boston in the late 1980s, during his early years as Artistic Director of the Handel and Haydn Society (America’s oldest continually performing musical organization, newly dedicated to HIP), producing broadcasts of their performances together for NPR. He would come into the studio regularly to record extensive interviews which were a masterclass in off-the-cuff erudition. Whenever we got onto the subject of Handel he would light up, and out would pour the most fascinating insights and anecdotes, clearly the result of deep study and profound empathy with the composer. So, it is little wonder that his recording of Messiah should not only embody this empathy, but also feel like a completely organic reimagining of the piece. There is no sense of the imposition of a particular scholarly or interpretative “point of view”, as has often been the case with later HIP recordings—not for Hogwood crazy fast tempi or mannered phrasing. In his rendition the work emerges whole: every aria and chorus presented in a just tempo, everything feeling just right in itself and in relation to everything else.

One of the ways in which Hogwood immediately placed his scholarly stamp on his rendition was his decision to present the work as a recreation of a specific performance for which we knew exactly what forces were used and which movements were included. This performance was given first at Covent Garden Theatre in London on April 5th, 1754, and repeated at the Foundling Hospital on 15th May.

Foundling Hospital, Interior

Foundling Hospital, Interior

Hogwood was able to put together his edition from the actual score and extant parts of that Foundling Hospital performance. This immediately solved significant textual issues—there has never been a definitive version of the work owing to the fact that Handel himself had authorized different versions of the work, with different arias and choruses included for different performances. The Foundling Hospital materials defined exactly what the number of orchestral musicians were, playing which instruments, along with the number of soloists and their voice types. The choir was one of boy trebles and male altos, tenors and basses. (Incidentally a detailed account of the history of Messiah, the various performances and the musicological and performing decisions made by Hogwood for the recording are all covered in superb essays by Anthony Hicks and Hogwood that accompany the set).

The college choral tradition in England has persisted through many centuries to the present, so for his choir all Hogwood had to do was turn to choose from one of the many top-class London or regional cathedral choirs, or Oxford and Cambridge College Choirs. L’Oiseau-Lyre and Hogwood had already recorded with the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral Choir and their music director, Simon Preston, so this was a logical choice. At the time of this recording of Messiah I was a student at Oxford and would regularly attend Christ Church Evensong or Sung Eucharist (at which a full Mass setting would be sung): not for religious reasons, but because I myself had grown up singing in similar choirs since the age of 8, and I loved hearing this incredible music—which ranged from Renaissance Masses by Palestrina and his contemporaries, to modern anthems by living composers—performed by a choir at the top of its game. And at this time (the late 70s/early 80s) Christ Church Cathedral Choir fast became my favorite. The boy treble sound was less ethereal than that of King’s, not quite as forceful as that of St. John’s, both in Cambridge. Also, Simon Preston, a virtuoso organist in his own right, brought a quality to his interpretations similar to that of Hogwood: to make the music sound fresh and newly minted, with buoyant rhythms, well-articulated syncopation, clarity of text (not always a given in such choirs) and a lovely blend of sound.

To match the smaller scale of his orchestra and choir, Hogwood turned to a younger generation of vocal soloists, many of whom had begun their careers singing in choirs like that of Christ Church and who were fully versed in the new notions of “period” singing. These notions included no constant vibrato, but rather an emphasis on beauty of natural tone, with vibrato held back for moments where it would color the sound according to the demands of text and musical line. Ornamentation, the process of adding runs, trills etc. to add variety in repeated sections of what were known as “da capo” arias, was applied tastefully and with restraint. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there was a deep, abiding commitment by Hogwood and his singers to presenting the actual text itself as though it mattered (which it does). These are beautiful words, drawn by Handel’s librettist Charles Jennens from different scriptural texts. It is essentially a collage, though assembled with a brilliant sense of dramatic flow and overall structural integrity. The way the work moves through alternating choruses, arias and recitatives is as surefooted as it gets, and in Hogwood’s hands this becomes a story that really matters. These ideas and sentiments, originally cast in words and music centuries ago, become newly relevant—and surprisingly moving—even to this irreligious listener.

Charles Jennens by Thomas Hudson

Charles Jennens by Thomas Hudson

The beauty and thrill of the solo singing never palls in this recording. I will pick a few choice examples, beginning with the opening recitative and aria by the tenor, Paul Elliott: “Comfort Ye, My People” and “Ev’ry Valley Shall Be Exalted”. Entering after the work’s instrumental curtain-raiser, the tenor sets the scene for all that is to follow. No pressure! In my book Elliott remains unsurpassed in his performance: his unforced, ringing tone in the long, sustained passages of the recitative is matched by his fleet passagework and buoyant rhythms in the faster aria that follows.

“Comfort Ye, My people……” with Paul Elliott (tenor)

One of the most thrilling passages in the whole work is the scene where the angel appears to the shepherds to announce the birth of Christ. This takes the form of an accompanied recitative where Handel’s genius for dramatic effect is fully on display with the writing for animated, fluttering strings reflecting the excitement of the scene (he was, after all, the most commercially successful opera composer of his time). Soprano Judith Nelson is both ethereal and dramatic, fully conveying the wonder of the moment. At the entrance of the choir (“Glory to God”) Handel adds trumpet to thrilling effect: I get goosebumps every time I listen to this.

There were shepherds in the field…..” with Judith Nelson (soprano 1)

Bass David Thomas has his stand-out moment during the depiction of how the Earth and its inhabitants will emerge from darkness with the coming of the Messiah. Again, this is Handel’s word-painting at its finest, and listen to how Thomas varies his use of vibrato and non-vibrato to convey the scene. Also note how Hogwood uses variety of articulation and micro-dynamics alone in the orchestral accompaniment to capture the drama of the text. This is marvelous stuff.

“For behold, darkness shall cover the earth…..” with David Thomas (bass)

In the weighty aria “He was despised and rejected” contralto Carolyn Watkinson and Hogwood give a masterclass in how to convey more with less. This aria can so easily get bogged down, but they keep it moving without in any way detracting from the seriousness of what is being described. Note the varied ways in which Watkinson shades the recurring words “despised”, “rejected”, “sorrows”, and “grief”, as well as the tasteful ornamentation in the repeated A section of the aria.

“He was despised and rejected….” with Carolyn Watkinson (contralto)

For many I will have saved the best for last. With only three arias on this recording soprano Emma Kirkby blazed into the musical firmament, and she remains one of the most beloved singers of the HIP movement to this day. Her contributions to this recording are indelible. I have picked her first appearance, where she follows David Thomas’s incendiary introduction with a performance of “But who may abide” characterized by her effortless purity (especially in the upper registers) combined with immaculate runs and fury in the demanding faster section “For he is like a refiner’s fire”. Listen to how she throws out isolated high notes with spot-on accuracy and hair-raising finesse. Heart-stopping.

“Thus saith the Lord…. But who may abide….” with David Thomas (bass) and Emma Kirkby (soprano II)

The performances and intimate scale of this recording created a very different experience from the ones most of us had experienced up to that point on record and in the concert hall. There is a sense here of being spoken to, of being engaged with in a conversation, rather than being preached to from on high by mass assembled forces. Nowhere is this clearer than in the contribution of the choir, and this reflects its daily role in the liturgical services in Christ Church Cathedral. By virtue of its size and its position in the building itself. Each side of the choir, a full complement of tables, altos, tenors and basses, faces the other across the aisle. This results in a more inclusive, almost discursive musical presentation. When you sing in a choir like this you are facing your opposite numbers, and you can hear each other much better than in the traditional concert-hall layout, where the entire choir faces the audience. In Christ Church Cathedral, as in other college chapels, there is a feeling of the congregation being invited into worship with a sense of shared intimacy. All these qualities can be felt throughout the Choir’s contribution to Hogwood’s recording, and nowhere are these better illustrated than in my favorite chorus in the work: “For unto us a Child is born”. Listen to how this percolates along with a beautifully sprung rhythm—no helter-skelter tempo here as we find in other period performances. Hogwood allows the happy celebration of the words, the effervescence of the musical line, to slowly build into overwhelming hope and joy. Is there any better expression of the fundamental meaning of Messiah?

“For unto us a child is born…..” with the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

The Best Way to Listen to Hogwood’s Messiah

At the time this set was released Decca was starting to move much of its pressing capabilities to Holland, so even a first UK pressing bears the legend “Made in Holland. Mastered by Decca Recordings Studio’s UK” on the record labels. On LP this is a fine sounding set, with a lovely warmth in the mid-range which is perfect for vocal music and the period sonorities. But be warned. This was also the time when record companies delighted in pushing the length of record sides to the maximum, so, alas, these records have a proclivity for inner groove distortion. This recording will absolutely reveal how well your cartridge is tracking: those boy treble voices will distort if your set-up, and the pressing, aren’t perfect.

A few years ago, I picked up a German pressing on Teldec Decca-Telefunken in the hopes these problems might have been alleviated. It definitely tracks better, and there is slightly more inner detail. However, commensurate to the added detail is a slight edge to the sound, which I attribute to the fact that it was probably Direct Metal Mastered (according to the copy displayed on Discogs - there is no sticker on my copy).

The original CD issue from 1984 was always a decent sounding set, but in 2015 Decca issued a remastered 2CD version that also included a Blu-ray disc remastered at 24-bit 96 kHz. The remastered CDs sound excellent (I cannot speak to the Blu-ray since I lack a dedicated Blu-ray player optimized for audio playback). In general, this is my go-to copy, though I still spin the vinyl when I want to hear that certain je-ne-sais-quoi. The handsome package is presented in the ubiquitous hardback book format, with discs squeezed into tight paper envelopes: you are urged to add CD inners to prevent scratching. The booklet’s superb original essays and period artwork are supplemented by a welcome reappraisal essay by Lindsay Kemp.

The Legacy

The huge commercial success of this recording sent a clear message: period instruments and HIP were box-office gold. All the major record labels doubled down on re-recording the Baroque repertoire with their respective early music artists. On DG Archiv that meant Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert, later joined by Reinhard Goebel and Musica Antiqua Cologne and John Eliot Gardiner with his English Baroque Soloists and the Monteverdi Choir who embarked on a massive trek through Bach’s Passions and Cantatas. On Decca L’Oiseau-Lyre Hogwood & co. was the main game in town, but smaller chamber groups like Anthony Rooley and his Consort of Musicke also recorded regularly. (It should be noted that all these English groups were drawn from the same pool of period instrument players). German labels continued to work with their period instrument stalwarts Nicolas Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt, Frans Bruggen and Sigiswald Kuijken. Harmonia Mundi, always a pioneer in recording early music, leaned heavily on the multi-talented instrumentalist Jordi Savall, whose soundtrack for the movie Tous les Matins du Monde became another juggernaut sales success in the early 90s. They also invested heavily in William Christie, an American harpsichordist based in France (who incidentally played on Hogwood’s Messiah) as he tackled the newly popular baroque opera repertoire. In America Sony cultivated the excellent Canadian group Tafelmusik and its leader Jeanne Lamon.

Back in the UK, EMI lined up the excellent Andrew Parrott and his Taverner Consort and Players for Baroque and earlier repertoire (many of their recordings are still top recommended renditions), and Roger Norrington for music from the later Classical and Romantic eras. Classical collectors will fondly recall the impact of his disc of Rossini overtures with its thunderclap period timpani. This expansion into ever later repertoire—now reaching into the 20th century with performers like Francois-Xavier Roth and Teodor Currentzis—has continued to reap commercial and critical success (though not without its detractors and skeptics, especially on the issue of when to use vibrato—misgivings which I frequently share).

An interesting sidebar: record collectors like myself who treasure our 50s and 60s records of the Vienna Philharmonic performing the central European masterpieces, or Ernest Ansermet’s Stravinsky, Debussy and Ravel recordings with the L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, all of which sound very different from modern recordings of the same repertoire—are we not also listening to “period instrument” performances…..?

In 2015, Gramophone magazine included Hogwood’s Messiah in its regular series of columns titled Classics Revisited. It’s fascinating to read about these two critics’ personal history with this recording, which has deeply touched generations of music lovers. I can hardly improve upon Lindsay Kemp’s summation:

“This recording is not only one of the shining lights of ‘historically informed performance’, forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew and strewing new ideas in our path; it also remains one of the most deeply convincing Messiahs we have.”

Hallelujah to that.

“Hallelujah” Chorus

Link to my video on “The Best Messiah?”

The site cannot incorporate "knobs" within features but here are the ratings where there would be "knobs":

Music: 11

Sound: 9

What To Listen To Next

Many AAM/Christopher Hogwood records litter the used record bins in excellent condition and are usually among primary recommendations for HIP versions of the repertoire. I will particularly recommend his series dedicated to the Theatre Music of Henry Purcell. On CD his recording of Haydn’s opera Orfeo ed Eurydice with superstar mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli is thrilling and a revelation; his almost-complete cycle of Haydn’s symphonies more controversial but well worth diving into—and far more listenable than the currently unfolding cycle on Alpha from Giovanni Antonini, which is often willfully eccentric. Less well-known are Hogwood’s later recordings of non-HIP versions of the wonderful violin concertos of Martinu for Hyperion, with violinist Bohuslav Matousec and the Czech Philharmonic, an absolute primary recommendation for these major works that are almost unknown. Hogwood’s forays into 20th Century neoclassicism with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra (Decca) and the Kammerorchester Basel (Arte Nova) are also terrific.

For an example of his exemplary keyboard-playing look no further than his 1981 recording of The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book for L’Oiseau-Lyre.

I also strongly suggest seeking out Hogwood’s delightful recordings of Handel’s op.3 and op.6 Concerti grossi with the Handel and Haydn Society on period instruments (L’Oiseau-Lyre).

One to avoid: his period instrument cycle of Beethoven symphonies with the AAM (although his account of the Egmont overture is pretty darn thrilling).

Of course, Handel’s works are copiously represented in the catalogue, not least his operas which have become THE hot ticket in opera houses around the world. You can’t go wrong with William Christie’s various recordings. A lesser-known choral work that has been getting a lot of traction of late is Handel’s Brockes-Passion, and new recordings by Jonathan Cohen with his band Arcangelo (Alpha) and Richard Egarr with the AAM on their house label can both be recommended.

.png)