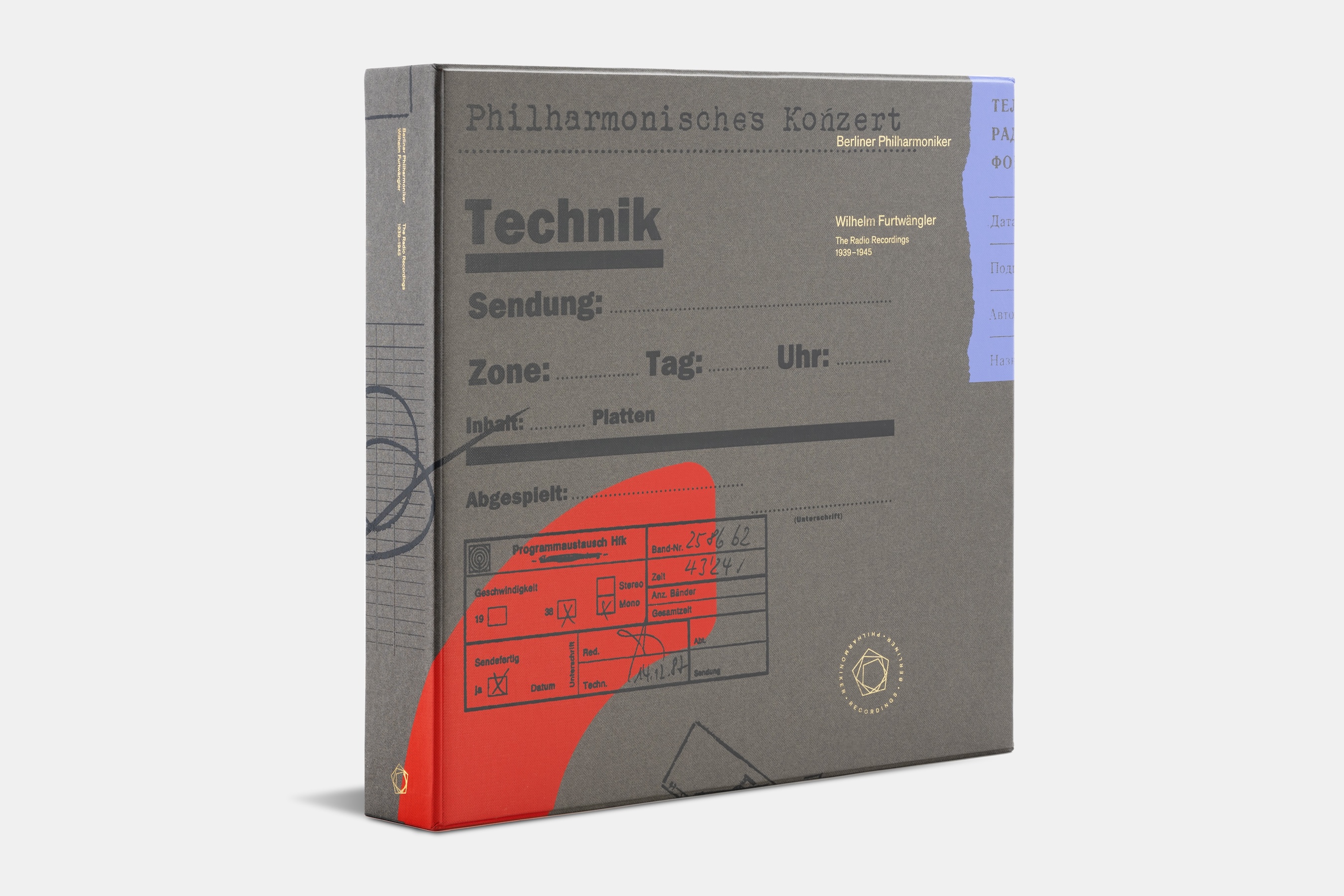

History Etched on Vinyl: Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra - The Radio Recordings (1939 - 1945) PART 2

The In-House Label of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra presents a Compelling Survey of the Legendary Conductor at work in Wartime Germany

Now, to the recordings themselves, and the important place they occupy in Furtwängler’s discography, and the central position that the Berlin Philharmonic concerts - and Furtwängler himself - occupied in Germany during World War II.

THE GERMAN CLASSICAL TRADITION DURING WARTIME

You can’t really appreciate the unique qualities of these recordings without understanding their context. This is not music-making taking place in a vacuum. As the British had the piano recitals given by Myra Hess throughout the War, and especially during the Blitz, to lend them fortitude, to soothe and inspire troubled minds and hearts, so too the Germans had the broadcasts by the Berlin Philharmonic under the internationally celebrated Furtwängler to help them keep the faith. As the War progressed, and the tide turned against Germany after its failure to conquer Stalingrad, these words by the popular music journalist Karla Höcker appeared in the programme book for the opening concert of the 1943/44 Season:

“We are gazing into the dark of a new winter, doubly dark for it is a winter of war… And in the midst of this darkness there rises, untouched by horrors of any kind, but gentle, enthralling and consoling, the voice of everlasting German music! We who are directly confronted with atrocities, we to whom the closeness of death has lent other, sorer feelings along with a new and tougher consciousness - we recognize more clearly than any previous generation just what this music symbolizes… Anyone who is truly touched by this music, who allows his own life to glow within it as in a great flame, belongs to the world of this spirit. And this is what makes these Philharmonic concerts… become in the midst of war not only a beautiful, more or less rewarding experience for individual music lovers, but a higher necessity. It is the complete, totally authentic, living embodiment of a spiritual world that greets us here, the invisible symbol of what millions of people bear within them. And with it the divine universal order, for at least a few hours and in the imperishable sphere of music, can find embodiment on earth.

“This is why we gather together for the concerts of the Berliner Philharmoniker. That is why we need them more than ever before, at the beginning of this fifth year of the war.”

Richard Taruskin, in his extensive essay on Furtwängler’s style and methodology in these recordings, included in this set’s excellent accompanying book, makes this important point, which goes to the heart of why these recordings are unique and important in this conductor’s discography:

“The extent to which the orchestra’s actual performances reflected the particular stresses to which Karla Höcker’s affecting programme essay called attention will always be a matter of conjecture and debate; but two things are certain. First, the attitudes it expresses, and the view of music it embodies, were traditional German attitudes and views, first enunciated by the earliest Romantics at the beginning of the 19th century. They were the views and attitudes on which the style of performance associated with German Romanticism was founded. What has made Wilhelm Furtwängler’s performances so durably valuable, and made his recordings immortal - still current and sought after more than 60 years after his death in 1954 - is the recognition that they were the quintessential embodiment of that style at its most accomplished and compelling. Now that performance practices have so fundamentally and irrevocably changed, partly in response to the horrible end of that very war to whose traumas the Berlin programme book bears witness, it is safe to say that Furtwängler set a historic benchmark that will never be duplicated, let alone surpassed. And the other things that is certain is that Furtwängler’s wartime live performances are the ones that show his style of performance at its most intense and persuasive, setting a benchmark within his own career that he himself never duplicated or surpassed. They are thus both historic and “historical”.”

The last disc in the original CD/SACD edition of this set (not, alas, on the vinyl set) concludes with a track that is utterly extraordinary, unlike anything I have ever heard or expect to hear in my lifetime. Unlike anything you will ever hear. I mention it because it speaks - in the most heightened manner possible - to what the Furtwängler radio broadcasts embodied in their essence, and also meant to the German people.

Even though this track isn't on the vinyl set, it is essential to discuss for precisely these reasons.

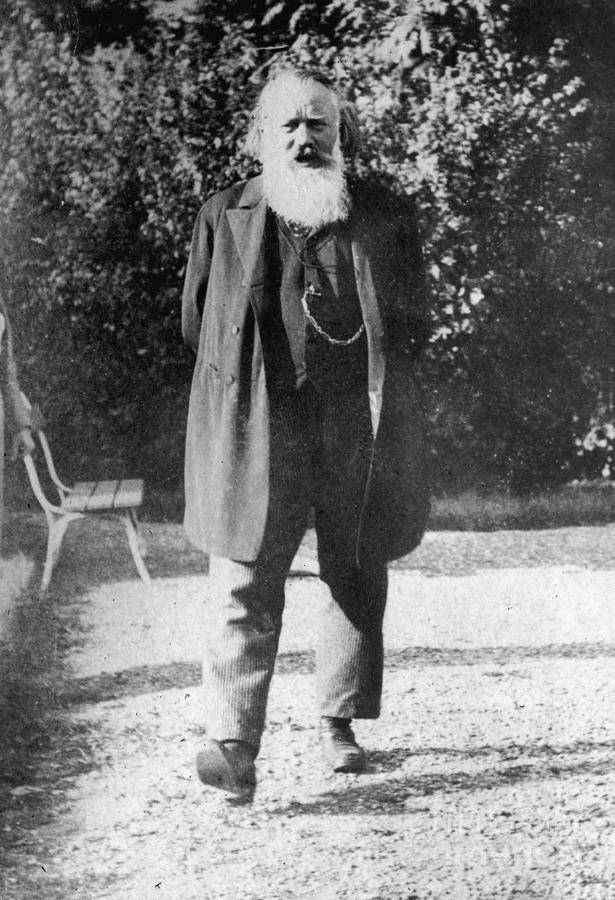

The track in question is the last movement of Brahms’s 1st Symphony (the rest of the recording has not survived). This movement speaks to something core in the German classical tradition. Coming at the end of a work which the composer struggled mightily to begin, let alone complete, over a span of 21 years.

Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897)

Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897)

Like all 19th century composers who followed in the footsteps of the (al)mighty Beethoven, the struggle to compose symphonies in the wake of the 9th Symphony’s über-embrace of symphonic form and expression pushed to the max was a Herculean task. The 9th, with its embrace of both Utopian and Promethean ideals; its transcendental statement of Man’s Higher Purpose and Ascendant Place in the Worlds of Nature and, basically, Everything, stood alone. Like a musical Everest it was unapproachable, unconquerable.

Brahms finally cracked it - or at least cracked it to the point that his own symphony is a complete success. And as with the 9th, the final movement of his First contains multitudes, standing as its own quasi-Beethovenenian Statement of Intent. When the hymn-like Big Tune enters on strings about halfway through the movement, then builds and builds, it feels like its own Ode to Joy (from the Choral Finale of the 9th): heroic, aspirational, comforting, transcendant, defiant.

The recording of the First in the CD box by Furtwängler and the Berliners took place at the end of January 1945, in the Admiralspalast (Admiral Palace) in Berlin, one of the few venues remaining un-bombed in Berlin that was big enough to accommodate orchestral concerts after the destruction of the original Philharmonie Hall. This was the last concert Furtwängler conducted in Berlin before fleeing to Switzerland. He had been declared persona non grata by Himmler and the SS.

You can hear why it was his last concert.

Clearly audible in the background is the sound of Soviet artillery pounding the city. Berlin fell on May 2nd after intense street fighting.

The Soviet Flag over the Reichstag

The Soviet Flag over the Reichstag

The booklet contains a detailed account of this fateful concert by the same Karla Höcker quoted above. The first work, a Mozart Symphony, ground to a halt after the power went out. Furtwängler tried to keep things going with players performing from memory in the darkness. Finally defeated, eventually the music trailed off into silence.

But after a period of time, the electricity and the lights came back on. Furtwängler moved straight on to the Brahms.

Karla Höcker:

"It is customary to repeat the last item after interruptions in a concert. But this time, no one is surprised that Furtwängler gives the downbeat for the Brahms symphony. It is as if Mozartean beauty, blissfulness itself, no longer has a place in this city."

Only the last movement survives on tape.

The performance reflects the reality of the city - and the German people - as all face ignominious and total defeat. The music burns with a white hot intensity that expresses many things: a country and a people about to suffer defeat, pride and fear co-mingled; a long and noble musical tradition defiant, but also fragile, uncertain of the future; there is even a tinge of self-awareness (or am I being fanciful), a sense of “Oh what have we done that we are come to this??”

What indeed?

Can you imagine the emotion in the hall as this music rang out, played by musicians who had suffered the privations of a long war? Something fully rooted in the shocking reality and emotion of the moment, yet also looking back to a centuries-old tradition - the central cultural tradition of a nation about to be brought to its knees - is being fully expressed here. It is conveyed with all the elemental power that this great orchestra can summon, pushed to extremes by a conductor himself at his most elemental. The music is by turns defiant, ferocious, baleful, tragic, anxious - and more.

All beyond words.

And every time the music subdues to a piano or pianissimos, you hear the distant booming of the guns.

As Richard Taruskin notes in his essay:

"In the most literal, etymological sense, it seems an act of atonement, putting all who hear it now at one with all who heard it then."

I wish this recording had been included in the vinyl set.

(N.B. This video is drawn from a different, inferior audio source to the one on the BPO official set).

The bulk of these recordings, dating from 1942 onwards, are suffused with some degree or other of the qualities heard in extremis in this Brahms performance. It is partly down to Furtwängler’s own way with the music: elemental, almost subterranean, alternately coiled and uncoiled with a power you would be hard pressed to hear elsewhere - then, now, or at any time in-between.

So what we have in this set is a series of recordings which, at their heart, are a profound statement of celebration and intent; of the overriding importance of the German musical tradition of composition and performance; and of the similar importance of works from other countries (some of which Germany was at war with) that Furtwängler felt to be equally integral to the classical tradition.

Ensemble can be quite scrappy, especially by today’s corporate (and increasingly homogenised) musical standards - Furtwängler’s beat was notoriously unclear. Neither performance of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony contained in the CD/SACD set (the superior of the two is on the LPs) manages to clearly articulate those famous four opening chords: Da-Da-Da-DAAAAAAHHH! But on that 5th from June 1943 which occupies one of the best sounding LPs along with a thrilling Coriolan Overture, who gives a damn! The performance is volcanic, fundamental, raging and tearing at the heavens. You get used to the sound very quickly and then all you can do is sit pinned to your seat. It is a very different beast to Toscanini in 1939 (the version to listen to is the one remastered by Pristine Classical, part of a cycle that should be in everyone’s collection); very different also from Carlos Kleiber in his benchmark account with the Vienna Philharmonic on DG from 1975 - a fiery statement of youthful vigor and passion.

The way in which Furtwängler and the Berliners speed up into a fury in the last minutes of the last movement of the 5th, then slow it right down for those massive final chords is not in the score, but sounds like Beethoven himself is conducting and going a little mad. And it’s wonderful! It is triumphant and terrifying in equal measure. It leaves Kleiber’s thrilling Finale if not in the dust, certainly a few strides behind.

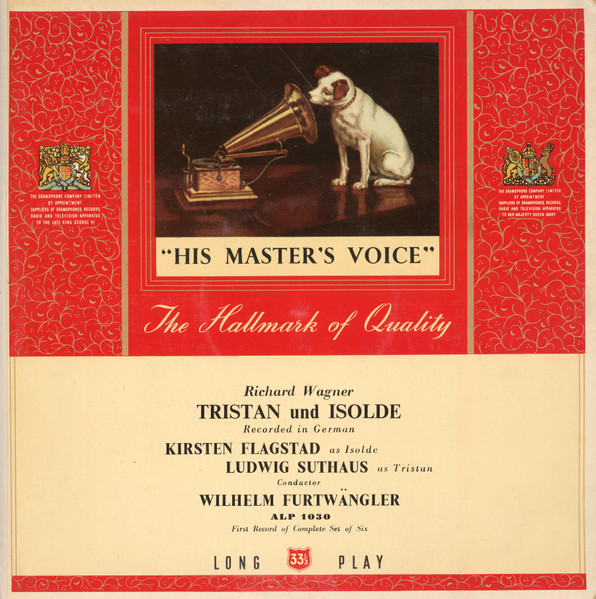

Turning now to another highlight: the Prelude and Liebestod from Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde. Wagner, like Beethoven, spoke to the core of Furtwängler’s being (as, regrettably, he also did to Hitler’s), and this performance burns white hot with a sense of passion unbounded, and imminent doom unlimited. The famous Tristan chord, announcing the suspension of traditional tonal resolution for the 4-hour duration of the opera, and heralding the convulsions of music in the early 20th century - atonality, serialism and the rest - here carries a weight and portentousness unlike any performance or recording I have ever heard. Furtwängler’s supremacy as a Wagner conductor is on display as he binds together the music’s deep undercurrents with a sense of inevitability that is riveting. By the time Isolde sings herself into oblivion (no soloist here - just the orchestra) with her finally achieved sexual and musical orgasm in death, there is a sense that civilizations might crumble as a result. Which, in fact, they did. It is quite a thought to imagine Hitler and the German High Command listening to this Call to Destiny on their radios as they waged their War on Humanity.

First 1952 Vinyl Ediition of Furtwängler's Complete EMI recording of Tristan und Isolde

First 1952 Vinyl Ediition of Furtwängler's Complete EMI recording of Tristan und Isolde

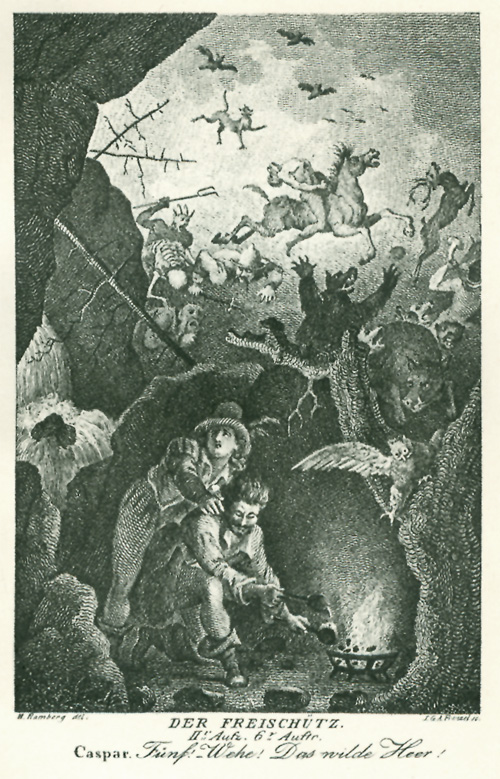

Another core work of the German 19th century repertoire, the Overture to Weber’s opera Der Freischütz, receives a similarly hagiographic outing under Furtwängler, once we get past the somewhat shaky intonation of the exposed horns in the atmospheric opening. This tale of common country folk warding off the interventions of the Devil is considered one of the first masterpieces of German opera, and an iconic early statement of German Romanticism. Much of the music in the Overture is drawn from the supernatural Wolf’s Glen scene, and Furtwängler and the Berliners elevate the theatricality of the piece into something truly mythical.

The Wolf's Glen scene from Der Freischütz

The Wolf's Glen scene from Der Freischütz

A more laid back German Romantic sensibility is on display in a persuasive account of the lyrical, lesser-known ‘Cello Concerto by Robert Schumann - utterly beguiling and a treat waiting in store for those of you unfamiliar with this work. The soloist, Tibor de Machula, is drawn from the ranks of the orchestra.

Similarly, the soloist in Beethoven’s iconic Violin Concerto, Erich Rohn, was the orchestra’s Concertmaster. This is a performance heavy on nobility - no surprise there. The final dance-like Rondo is a maybe a little more heavy-footed than we expect these days, but it all works to great effect. The recorded tone for both solo violin and ‘cello in these concertos is more than acceptable, with little hint of the kind of stridency you would normally expect from recordings of this vintage.

We have a clutch of first-rate renderings of tone poems by Richard Strauss, at the time Germany’s elder statesman of music. Any sense that Furtwängler was predominantly a “slow” conductor is dispelled by his vivacious, fleet-of-foot account of Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks - the orchestra and conductor sound like they are on vacation, having the time of their lives. Don Juan is a work I find to be somewhat tiresome, but this performance is thoroughly persuasive, full or energy and vigour. Likewise the performance of the lesser-known Sinfonia Domestica, in which the composer elevated his home family life - misbehaving children, connubial bickering and bliss and all - to the level of Significant Symphonic Utterance, is utterly engaging. It’s a most peculiar work that has grown on me over the years. My preferences here are with Reiner on RCA Living Stereo, Karajan and Kempe on EMI, but Furtwängler and the Berliners put this curio over with real panache.

As is so often the case with conductors one has pigeon-holed in one’s mind, the big surprises here are in repertoire one would not immediately associate with Furtwängler. The two (incomplete) suites drawn from Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloe are sinewy, incandescent, riveting, and offer a level of seriousness, even profundity, you may not associate with recordings from the usual Francophile suspects. It's wonderful to be able to hear Furtwängler's take on this gorgeous music.

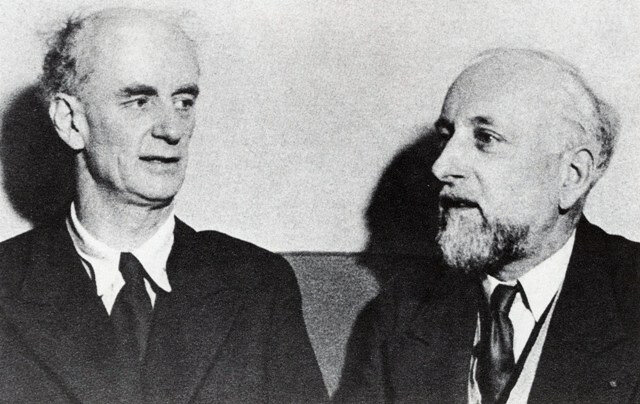

Furtwängler with the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet in February 1945, shortly after Furtwängler had fled Germany. Ansermet's own recordings of Ravel on Decca/London are central recommendations for this repertoire on vinyl and CD

Furtwängler with the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet in February 1945, shortly after Furtwängler had fled Germany. Ansermet's own recordings of Ravel on Decca/London are central recommendations for this repertoire on vinyl and CD

Likewise Sibelius’s En Saga is epic and on fire (anticipating the mastery of Furtwängler’s successor at the helm of the BPO, Herbert von Karajan, in the Finnish composer’s music). Both the Ravel and Sibelius recordings are unexpected highlights of this set, and will have collectors yearning for more of the same from Furtwängler.

Furtwängler with Jean Sibelius

Furtwängler with Jean Sibelius

Are there any duds?

Well, I found the Overture to Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nuremberg to be as taxing on my patience as it always is (as is indeed the whole opera, which makes me a bit of an outlier, I know). The sound is far from the best this set has to offer. Likewise the Handel Concerto Grosso feels (and sounds) like an excavation from musically prehistoric times: what should be a Baroque divertissement for deft young things flitting garrulously around a Palace ballroom is instead a courtly dirge of stale small-talk uttered by corpulent, aging aristocrats barely contained by their corsets. Admittedly, as the piece gets into its stride, you can discern Furtwängler has a certain way with it, but I wish this had been left out, and maybe that apocalyptic final movement of Brahms 1st Symphony I discussed earlier substituted instead.

Another core work of the German Romantic repertoire, Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, receives a compelling performance, marred only by some persistent and annoying hum. Nonetheless, I understand why this was included - it is an elegaic, haunting rendition of a work than can often seem routine.

The set is rounded off by Mozart’s 39th Symphony in a performance which is hardly revelatory, but never workmanlike. But in all honesty this is not music I burn to hear Furtwängler conduct. That passion I reserve for the Beethoven, Wagner, Ravel, and Sibelius performances I have singled out in this set, and I suspect you will be as surprised and thrilled to hear them as I was.

There is a sense throughout that Furtwängler is on a mission, a mission to protect and promulgate music that, for him, represents all that’s essential about Western Civilisation, the only thing that matters in the face of a War that threatens to consume all.

Wilhelm Furtwängler by Emil Orlik

Wilhelm Furtwängler by Emil Orlik

His ongoing battles with the Nazi Party, some of which are detailed in the book’s essays, speak to his idealism - and his almost ridiculous (in context) propensity to insist on certain things when such demands and obstinacy would be enough to get anyone else shot!

He could be petty minded and insecure. He definitely used his favor with the Nazis to solidify and protect his power within the musical establishment (keeping that interloper and pretender to the BPO throne, Herbert von Karajan, at bay). But he also seemed in so many ways unworldly. I mean, he keeps telling Himmler and Goering “No” when it comes to releasing recordings for broadcast.

Here we have Goebbels, as close to the Führer as any, Head of the State’s propaganda machine, and one of the principal architects of the Holocaust, noting in December 1942:

“Furtwängler is a very idiosyncratic and stubborn figure. He is happy to make use of the National Socialist state’s resources when they serve his purpose.”

I would not have liked to be the subject of that memo.

In another entry earlier that same year, Goebbels notes Hitler’s personal involvement in events:

“The Führer tells me that Furtwängler is said to have performed a rather atonal concerto by Holler. [Anything that smacked of modernity, like atonality, was a big No-No! Composers of such “Entartete” music had gone to the Camps for less - MW] I will look into this immediately on my return…”

But clearly, whatever annoyances the conductor engendered amongst the Nazi ruling élite were excusable when the music-making was of such a high order - and such an integral part of not only keeping morale high, but also embodying the essence of the German national identity. The music, not surprisingly, seems to have become more and more important to everyone as the tide turned against the country.

With members of the orchestra, 1933 (Photo: Berlin Philharmonic Archive)

With members of the orchestra, 1933 (Photo: Berlin Philharmonic Archive)

So it is hardly surprising that the recording of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony I mentioned earlier is suffused with foreboding but also a certain still joy - joy seen in the rear mirror. An elegy for the nation as it once was, or imagined could be - perhaps. Recorded just over a month before that apocalyptic Brahms 1st, it feels like a declaration of intent: we will survive through all adversity, we must survive, and so will this music of the country’s heart and soul.

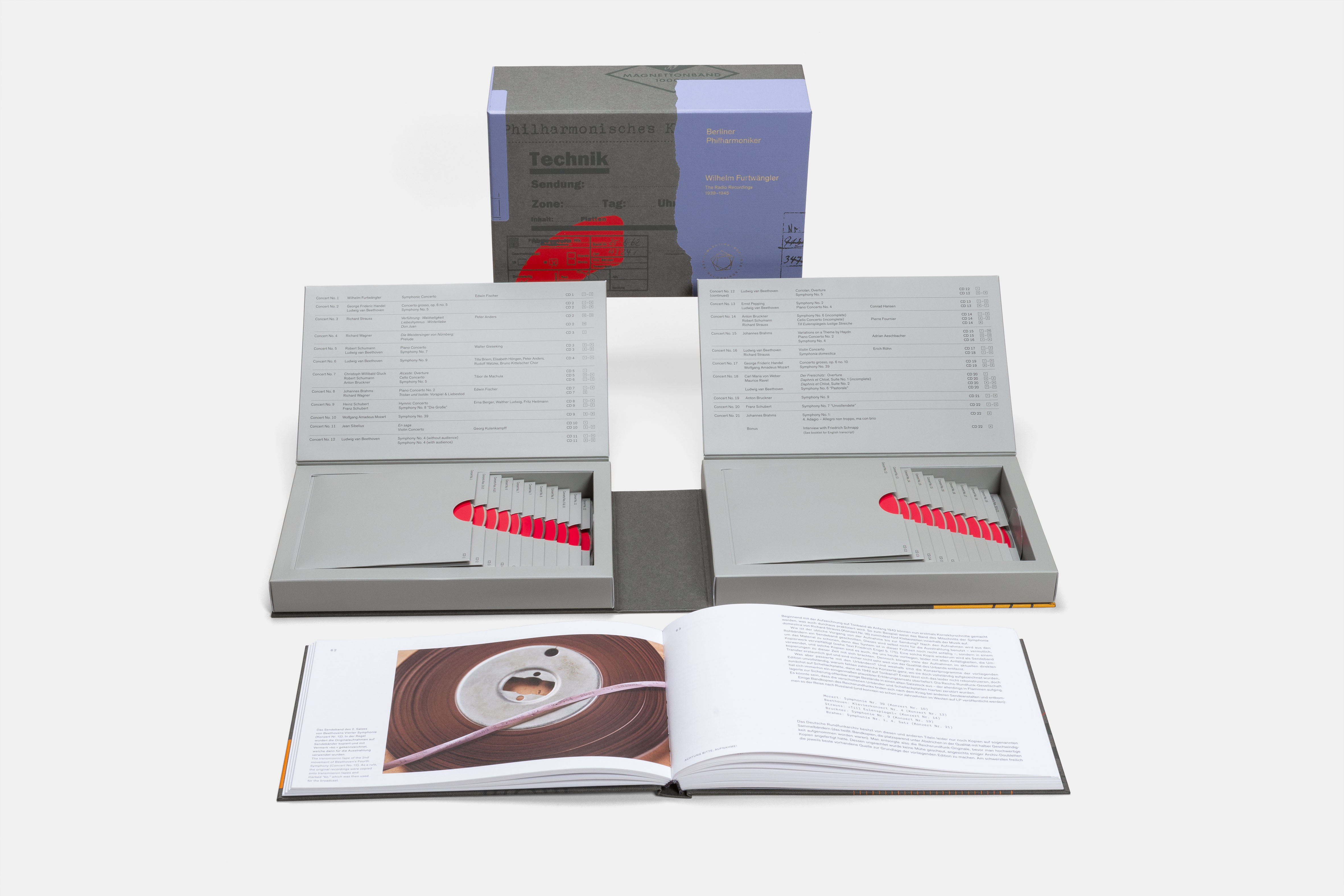

More of the remarkable history that lies behind these recordings is contained in another excellent essay in the accompanying book, this time by Eric Schulz. (Schulz was one of the prime moving forces behind the creation of this box). This book will keep you fascinated for hours by the extraordinary stories and history associated with these iconic recordings. It is a veritable feast for anyone remotely interested in the history of recording and/or Furtwängler, and is peppered throughout by endlessly fascinating photos (some of which also adorn these articles).

The only remaining question for anyone interested in this set is whether to buy the “complete”, comprehensive 22 CD/SACD box, or the more selective, limited edition 8LP box.

Completists will definitely want the larger CD/SACD set, but I will state unequivocally that the vinyl versions offer a more inviting listen (which, of course, may be down to sonic characteristics in my vinyl playback chain vs. my digital chain). During my final listening session I went through some four LPs in one go quite happily, riveted once again by these performances. This vinyl set will therefore be more than sufficient for the average classical collector or Tracking Angle reader curious as to what all the Furtwängler fuss is about. There isn’t a prohibitively weak performance amongst those selected for the vinyl treatment (although that Handel comes pretty close, and is definitely an acquired taste). The sound on a few tracks (eg. the Meistersinger Overture) does suffer in comparison to their better sounding fellows.

I will reiterate that the sound is a long way from what most audiophiles expect from their systems, even those of you accustomed to listening to mono records from the 1950s. Having said that, because these new transfers are sourced from the original reel-to-reel masters, or tape copies of same, there is a fidelity that far exceeds most other recorded material of this time. Listen past the sonic shortcomings (which your ears will adapt to rapidly) and you will recognize that this is something very special indeed. You will be eavesdropping not only on a conductor/orchestra partnership unique in the annals of classical music, and an era of music making quite unlike any other, but you will also be catching a glimpse of History itself in the making.

A History, which, unless we are diligent, will all too easily repeat itself, with outcomes possibly less friendly than they were in 1945, and which few can predict. Art does not always triumph in the face of Tyranny, as the many composers and musicians who did not find the same favour with the Nazis that Furtwängler did discovered as they were hauled off to the camps. Furtwängler himself may have survived the demise of his patrons to conduct another day, but the inescapable fact remains that his formidable musical legacy will forever be tarnished by his association with the Nazi regime - whether or not he was fully on-board with the ideology that drove that regime.

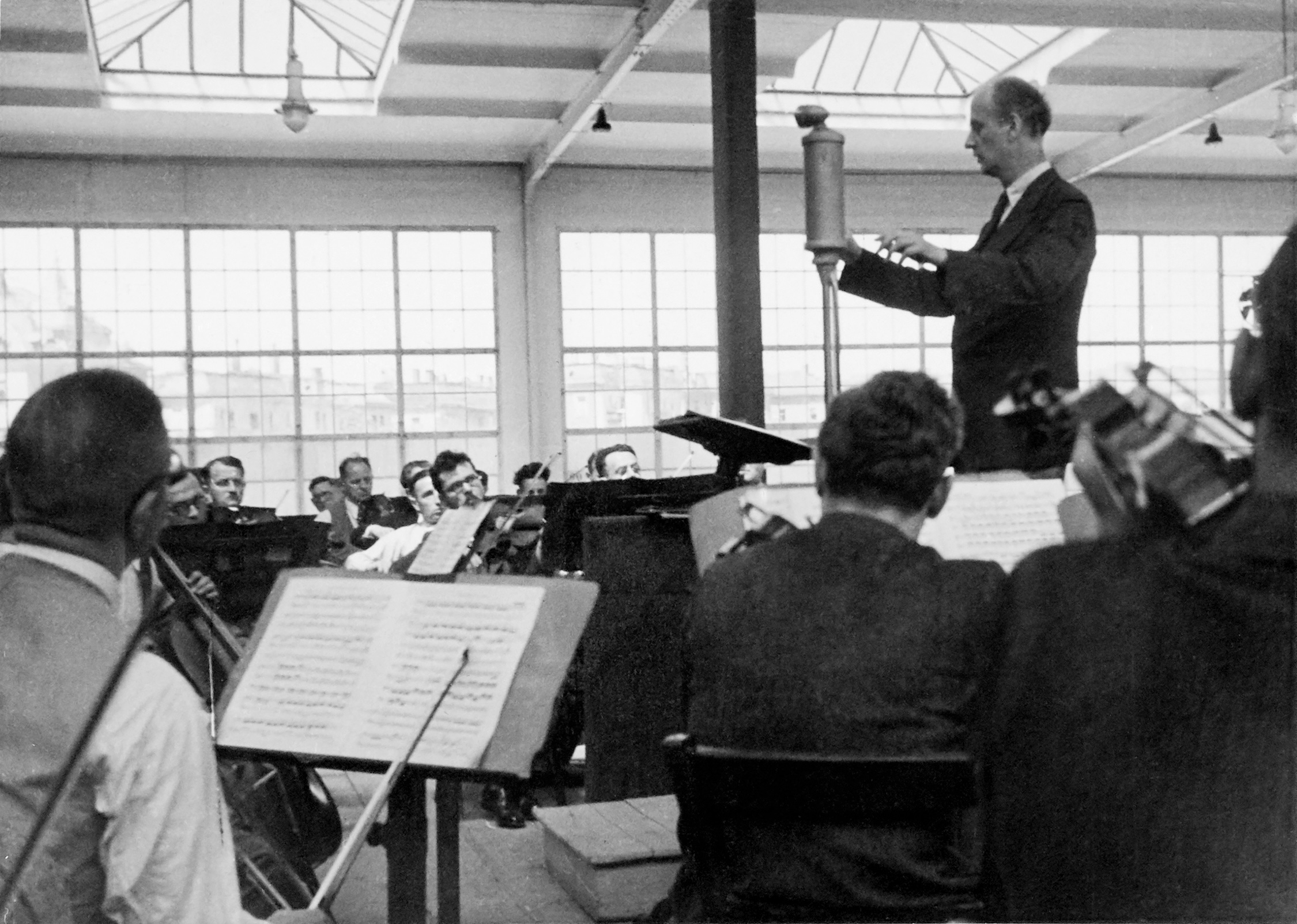

Furtwängler and the BPO in rehearsal in the Munich Rehearsal Hall, 1935 (Photo> Berlin Philharmonic Archive)

Furtwängler and the BPO in rehearsal in the Munich Rehearsal Hall, 1935 (Photo> Berlin Philharmonic Archive)

How much of the power of his interpretations as recorded here derives from his identification with a fervent belief in German culture, its essence, even its superiority, and the need for it to survive and thrive in the face of all opposing currents? A great deal. But this belief is also what lay at the heart of National Socialism’s drive towards nationalism, totalitarianism, and racial purity, Does the good part of Furtwängler’s belief in the inherent greatness of the German classical tradition (a belief shared by his rulers), a belief which lay at the heart of Furtwängler’s credo and method - how much of that gets tainted by the bad part which results in death camps, subjugation of freedoms, the enslavement of thought and limb, and, ultimately, the creative spirit itself?

In the right circumstances anyone can find themselves whistling the Ode to Joy as they and their fellow kinsmen march towards the abyss.

I’m not sure that Furtwängler himself ever really confronted any of these questions. He was too busy wrapped up in his world of music and, let’s be honest, surviving to make music. That was the priority, that was the thing he needed to do.

But you the listener, if you are at all alert to all that is implied in this music and these musical documents - the full context of these performances and recordings - you will be confronted by these questions as you listen to this set, and so you should be. Man is not an island, and nor is his art.

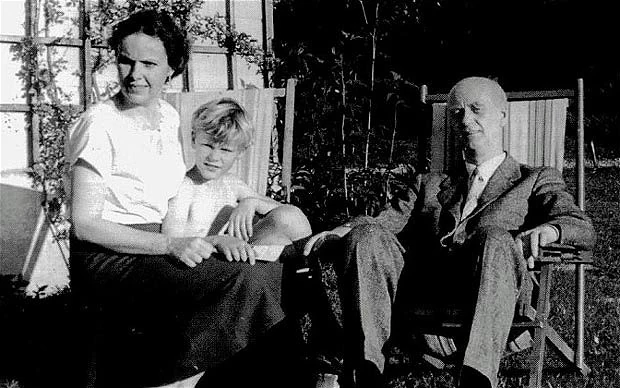

Wilhelm with his wife Elisabeth and son, Andreas

Wilhelm with his wife Elisabeth and son, Andreas

Alas, the kinds of issued raised by the historical context of Furtwängler's career, are once more to the forefront. Today, in much of the world, once again citizens of every hue are -or will be - forced to confront these questions and more about core moral values, let alone how to physically survive, as their societies tilt away from the liberal democratic world order that predominated in the West in the wake of World War II.

To hear Friedrich Schnapp tell it (he was Furtwängler’s engineer through the majority of these recordings), the conductor himself was disengaged from the political context of these performances:

“I knew… where I stood with him and that made our friendship – if I can call it that – even closer. It was clear from this that he never agreed with the cultural policy of the Nazis. I know from personal conversations with him that that was so. He also never greeted others with “Heil Hitler” and that took a lot of courage. Then, he was simply appointed to the state council. He couldn’t do anything about that. And when people strutted like peacocks into the artists’ room and greeted him, standing to attention, with the German salute, he just murmured something like “hello”. The words “Heil Hitler” never passed his lips. He was human – what can I say? As a person, he was beyond reproach, but he had little understanding of politics, and that’s something you can’t blame an artist for, God knows.”

Nevertheless, for this listener at least, there remains a streak of idealism and zealotry in Furtwängler’s music making which is both exhilarating and unsettling. It is especially pronounced in these wartime recordings. Historical context is an intrinsic part of the mix. Ultimately, is it the tension inherent in the unique historical circumstances of these sessions that - more than anything else - lends Furtwängler's interpretations their unique power? (I will confess that the desire to frame every musical utterance with "Significance" does result in some fatigue over the long haul - you will want to pace yourself in your listening sessions).

As you listen to the power of Furtwängler’s interpretation of Beethoven’s 5th from June 1943, can you avoid the speculation that what is driving the conductor and players’ unbelievable force of utterance is not simply some secular celebration of the overcoming of Fate, but rather a belief in the divine Beethoven incarnate, sent to inspire and save the Country and its People, and all that implies beyond the concert hall? And therefore should we be be so admiring and enjoying of an interpretation that embodies such inclinations, and which the Nazis themselves felt served their propaganda purposes? I defy you not to wonder it, even as you marvel at the performance.

Encounters and questions like these are not common to our listening rooms. All the more reason to celebrate a set of recordings which prompt such unsettling, but necessary, contemplation, even as we are thrown back in our seats by the forcefulness of the music-making.

Concert in the old Philharmonie, probably on 30th September, 1935 (Photo: Rudolf Kessler)

Concert in the old Philharmonie, probably on 30th September, 1935 (Photo: Rudolf Kessler)

Berliner Philharmoniker: Wilhelm Furtwängler - The Radio Recordings (1939 - 1945)

8 Vinyl LP set

Music: 4 - 10

Sound (Historical): 4 - 6

(N.B. The above ratings are more or less irrelevant - especially the ones for sound. Let the text be your guide as to whether this set is for you).

Available for purchase directly from Berlin Philharmonic Recordings. It's also worth hunting around other retailers like Presto Music in the UK; Acoustic Sounds, Elusive Disc in the US, who often have competitive pricing in your region.

Original recordings made between 1939 and 1945 by the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft

Digitally transferred from analogue sources from the archives of Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (rbb) and Stiftung Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv (DRA)

Digital transfer rbb: Nikolaus Löwe

Digital transfer DRA: Claudia Schiedewitz

Audio Supervision: Christoph Franke

Remastering: Christoph Franke, msm Studios, b-sharp, Leonie Wagner, Thomas Bößl, Alexander Feucht

The analogue-digital conversion was performed using a NEXUS XMIC+ with patented TrueMatch technology

Vinyl LPs Mastered and Cut at Emil Berliner Studios

Pressed at Pallas, Germany

Executive producers: Olaf Maninger, Robert Zimmermann

Idea and concept: Eric Schulz

Project manager: Felix Feustel

Art direction: Studio Marek Polewski

With many thanks to the folks at Berlin Philharmonic Recordings and Stefan Stahnke at Worte über Musik (Words over Music) for invaluable assistance in sourcing many of the photos used in these articles.

DEDICATION TO MISTY - MY DEAR DEPARTED LISTENING COMPANION

"When's the music starting...?"

"When's the music starting...?"

I trust my regular readers will indulge me as I dedicate these Furtwängler articles to the recently departed Misty, a much beloved family feline who had reached the Grand Old Age of 21 when she passed just two weeks ago as I was working on these. (Those of you who view my YouTube channel, Music on Record, will have seen her featured a few times recently as she commanded me (with her imperious caterwauling) to take a break from expounding on the virtues of various records to give her some far-more-important attention.

Misty was intimately involved in my work for Tracking Angle. She always sat next to me, or on my lap, as I listened to records, many of which I was soon to be writing about. The day before she died she was clearly ailing, but nevertheless sat closely nestled to my side, or on my lap, purring vociferously, as I completed my final round of listening for this Furtwängler epic - some 3 hours worth in one glorious stretch! (I think she rather enjoyed Mr. F.'s music-making!)

At other times she would regularly (ie, approximately every hour) interrupt my tapping at this keyboard to demand one or more of the following: 1/ food (especially Greenies treats); 2/ water in the form of a saucepan of same poured over our succulents in the courtyard, from which she would take her refreshment (this elaborate ritual is shown in one of my videos); 3/ attention in the form of pets, chin rubs, head rubs, ear rubs etc. of the hopefully endless variety.

When she was younger and livelier, Misty and her sister Rose, and later the new addition to the household (aka "the Interloper") Tootsie, a snowshoe (and, I fervently believe, the reincarnation of a 1920s “flapper”) adopted at the tender age of 12, all had a remarkable and persistent talent for walking over my computer keyboard at exactly the wrong moments, settling in front of the screen, complaining when I tried to move them etc. (Cat owners will recognize).

Why indeed should I be paying attention, at any time, to anything or anyone but them?

Misty has now joined her housemates in the Vale of Perpetual Catnip and Naps, and I am saddened to the core of my soul. She and her companions all loved music, and would perch nearby (or on my lap or chest) as Beethoven or Bach or Bowie or Miles played Pied Piper to those rats which never came (but the cats always thought might well do so).

Many a composer treasured a feline or canine daemon, often glimpsed in the corner of faded photographs. A muse to a composer or artist or writer can take many forms, but for me when I was writing about music or anything else I had only to look up, and for more years than I can remember there was my Misty, my own enigmatic muse. Either cosily asleep, nose buried deep in her paws, or sitting alert with her prominent “triangles” primed for chit-chat. “What’s going on?” I would ask her, to which she always had some kind of reply. A cat’s day, even that of a semi-retired mouser, is a busy one, and there is always much to discuss.

I shall always think on my little furry companion, my audiophile feline, whenever I play a record or write something for this site. In those times she will be near to me, as she always had been for many, many years. That’s a lovely and comfortingly tangible thought when contemplating the loss of a dear friend and companion.

Which Misty most indubitably was.

.png)