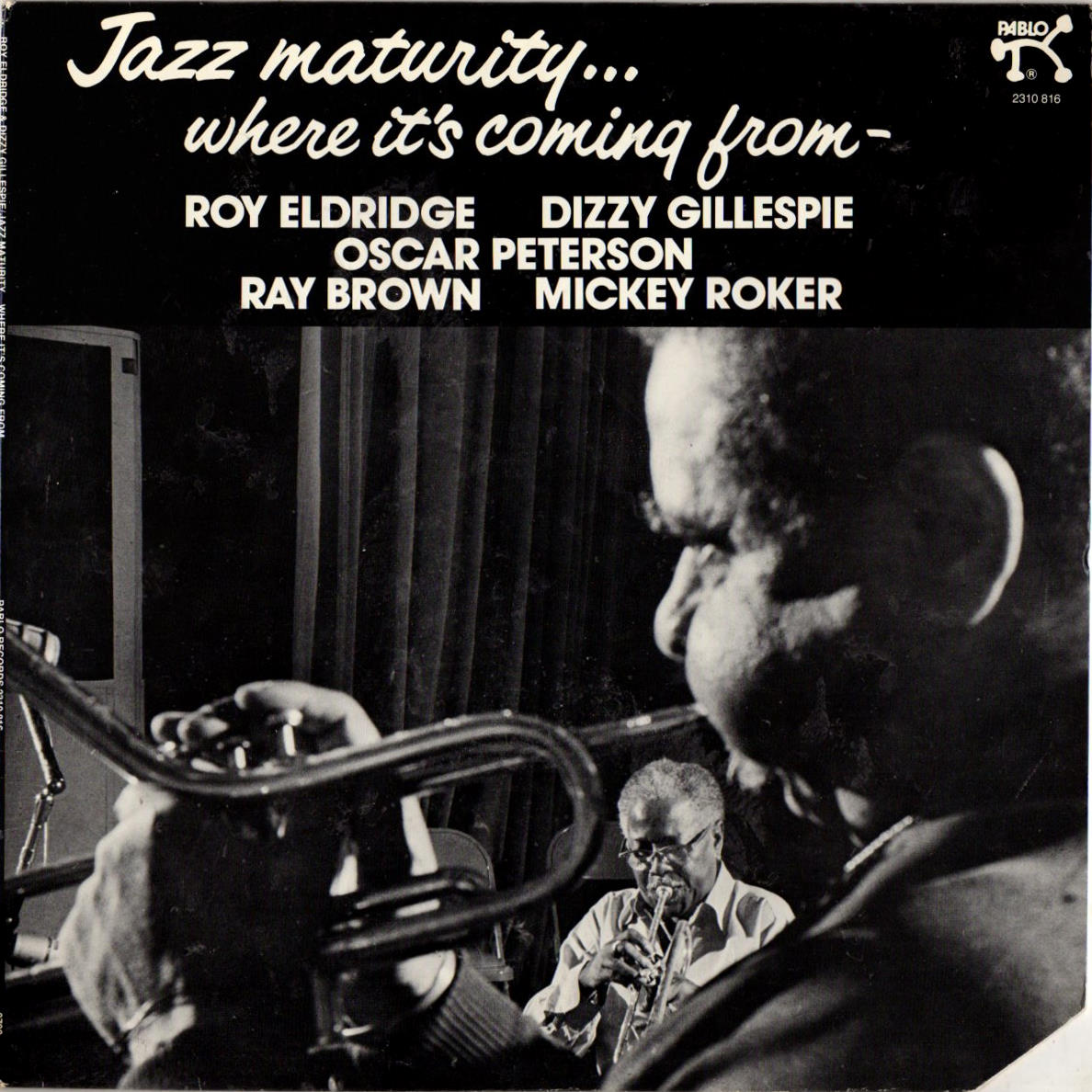

"Jazz Maturity....Where It's Coming From"——Dizzy Gillespie, Roy Eldridge

"The records you didn't know you needed"--- #13 of an occasional series

By the early 1970s, time had passed jazz by. The Beatles had happened, James Brown had happened, and “The Sixties” had happened. Young people, both Black and white, weren’t interested in jazz. It was the music of old people who didn’t buy many records or go out to clubs and concerts. Jazz musicians were scuffling for the few available gigs, driving cabs, and working at the post office. Even icons like Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, and Ella Fitzgerald were having difficulty selling records, and all released albums of pop/rock tunes. The fusion music of Return to Forever and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, the smooth/funky jazz of Donald Byrd and Grover Washington Jr., and Keith Jarrett’s sui generis Koln Concert was the “jazz” that was selling.

In 1973, Norman Granz, who had promoted the hugely successful Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts and produced some of the greatest jazz records for his own Verve label until he sold it in 1960, decided with complete indifference to the times and music business economics, to form a new jazz label called “Pablo.” Until he sold it in 1987 to Fantasy Records, Granz recorded Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, Dizzy Gillespie, Roy Eldridge, and a host of other jazz greats. He never recorded fusion, funky jazz, semi-jazz pop singers, free jazz, spiritual jazz, or even hard bop.

Instead, the Pablo catalog consisted almost entirely of early 50s style swing to bop played by many of the same artists who had recorded for Verve, and the albums were recorded in the same minimal production, loose, informal style. He was a man whose business skills had made him wealthy and the owner of one of the world’s finest collections of Picasso artworks, so one has to wonder whether Pablo was ever intended to make money or was instead a quixotic attempt to recreate a bygone era of music that he viewed as far superior to contemporary “jazz.”

On September 19, 1974, Granz recorded the album Dizzy Gillespie’s Big 4. The recording career of Gillespie (1917-1993) had been floundering commercially and artistically. He had recorded a forgettable album of rock/pop tunes for a small independent label and several lackluster albums of rock and funk-influenced jazz for another. For Granz, he recorded the type of music he had helped to create in the late 1940s and wanted to play-- swinging, no hyphen, bop jazz.

On the same day, Granz, who loved to record multiple horn jam sessions, also recorded Gillespie with three other trumpeters backing blues singer Joe Turner for an album entitled The Trumpet Kings Meet Joe Turner. One of the other “trumpet kings” was the great Roy Eldridge (1911-1998), nicknamed “Little Jazz,” whose career had been in the doldrums since the early sixties. Reduced to playing a long residency at a raucous Manhattan “Dixieland for drunks and tourists” club, he had only recorded three albums in the previous thirteen years.

Eldridge, a particular favorite of Granz’ and mainstay of the Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts was a fiery, ultra competitive player who terrorized other musicians at jam sessions with his ferociously hard swing and stratospheric high notes. He and Gillespie had history together. Eldridge was the next step after Louis Armstrong in the evolution of jazz trumpet. Gillespie was the step after Eldridge. As a young musician, Gillespie idolized and learned from Eldridge, who was never entirely comfortable with bop and always eager to show Gillespie he was still the teacher. Granz had recorded them sparring together in a joyously combative session in 1954.

On the Trumpet Kings session, Eldridge was obviously thrilled to be playing real jazz with his peers and brought his trademark “let’s see you follow that” intensity. The greats always play their best in the presence of other greats. Gillespie was ready to not only “follow that” but to give Eldridge something to take home with him. Sparks flew between them, and Granz knew some special musical magic would happen if he brought Eldridge and Gillespie together in the studio with the right rhythm section.

On June 3, 1975, he did that and recorded them backed by Oscar Peterson (piano), Ray Brown (bass), and Mickey Roker (drums) in what amounted to a follow up to the 1954 Roy and Diz session, which also featured Peterson and Brown. The format was the same— an informal blowing session on some blues and common standards. The style was the same, too—no modal tunes, no complex harmonies, no pop/rock tunes, no free playing, just hard swinging, bluesy swing/bop.

The album begins with the aptly named “Quasi-Boogaloo,” a simple 12 bar blues played over a funky beat laid down by Roker (1932-2017), who was, at forty-two, the youngest member of the group. Eldridge’s tone is showing some roughness and rasping at the edges, and the high notes aren’t as high or as pure as they were in 1954, but he plays a nice solo and shows that the old man had heard some funk records. Oscar Peterson (1925-2007) plays a virtuosic solo with blues licks at blazing speed, contrary motion runs, and counter rhythms piled upon counter rhythms, all played with incredible rhythmic momentum. Gillespie’s solo is full of long melodic lines interspersed with passages digging hard into the rhythm and some exciting high notes.

Billy Strayhorn’s “Take The A Train” is the most recently composed non-original on the album, and it was already thirty-four years old. They play it at an unusually slow tempo, and while the tune isn’t a blues, they make it feel like one. The intro features the gorgeous bass sound of Ray Brown (1926-2002) as he and Peterson improvise on the melody. When Brown shifts into a walking feel, the surge of forward momentum is Porsche powerful. Gillespie plays two muted choruses of relaxed, flowing melody with some bluesy wails. Eldridge sounds like he’s having trouble with his embouchure and can’t get anything going. Peterson plays one of those solos that hardcore jazz buffs say he always plays---flashy but empty. There doesn’t seem to be any arrangement, and now everything goes off the cuff. Gillespie and Peterson trade some incredible fours. Gillespie and Eldridge solo again, Eldridge fiery and swinging hard this time. They improvise on the melody together, then suddenly, urged by Brown, go into double time feel on the bridge before finishing by trying to outdo each other with high note pyrotechnics.

“I Cried For You,” usually played as a slow ballad, is taken at a mid tempo swing. Gillespie and Eldridge each solo muted for two choruses. Gillespie plays long surging melodic lines with some harmonic and rhythmic twists. Eldridge toys with a melodic idea, altering the rhythmic emphasis continually while swinging hard with increasing momentum. The rhythm section feels his intensity and starts pushing him even harder while staying relaxed. His second chorus is a gloriously swinging masterpiece. Peterson then plays a mind boggling, two handed display of virtuosity with melodic ideas, runs, and rhythms exploding like skyrockets. If you’re not dazzled, you ain’t paying attention.

“Drebirks” is a mid tempo twelve bar blues in A flat. Dizzy, muted again, plays six choruses of very hip, non cliché blues lines that seem to flow effortlessly and endlessly with constantly varying attack and rhythmic emphasis. It’s a supreme jazz statement, displaying astonishing creativity and amazing breath control. Those puffy cheeks were not for clowning. Eldridge takes seven grooving choruses, staying in the lower range of the horn before Peterson plays a solo that is maybe too self consciously funky. They’re just jamming, so piano and drums drop out, and Gillespie and Eldridge improvise call and response over Ray Brown’s melodic and swinging playing that, as always, has that indescribable combination of relaxation and insistence that all the greats have. Roker and Peterson come back in, and some of the hardest swinging you’ll ever hear commences.

“When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” was probably played as a tribute to Louis Armstrong, whose theme song it was. It’s played slightly faster than ballad tempo with a jazzy feel (as if these guys could play anything without a jazz feel). Eldridge plays the melody sounding like Armstrong and then a bluesy, nostalgic, but not sentimental solo. Peterson breaks the mood with more aggressive swing, and he lets his technique take him too far from the melody. Ray Brown’s bass solo is a superb melodic improvisation that displays his flawless technique and beautiful sound. Gillespie, with Mickey Roker’s sensitive and supportive playing under him, starts with his own Armstrong tribute before playing some complex bop runs of the type he invented and ends on a high note climax with Eldridge joining in.

The album concludes with “Indiana,” a song from the earliest days of jazz, the chord structure of which was the basis of many bop tunes, most notably “Donna Lee,” usually credited to Charlie Parker, though Miles Davis also claimed authorship. They start with Eldridge playing the melody while Gillespie improvises, using some avantgarde, Don Cherry-like tonal effects. Eldridge’s solo is a melodic improvisation played with his unique tone and punching rhythm feel. Gillespie enters with a hot wailing repeated run and then proceeds to play a masterful solo that seems to be on “Indiana” and “Donna Lee” simultaneously as he quotes melodic fragments from both and goes beyond bop harmony, sometimes sounding like the young Freddie Hubbard or more accurately sounding like the young Freddie sounding like him. Oscar Peterson tears through the chord changes, showing that he had heard Bud Powell’s 1947 version of “Indiana.” Gillespie and Eldridge trade eights to take the tune out, and Eldridge throws caution and concerns about saving his chops for his Dixieland gig to the wind and initiates a high note contest. Dizzy, the band, Granz, anybody who knew Eldridge, anybody who knew jazz, knew what was going to happen. Dizzy plays some blazing high note “top this” licks. Eldridge matches him and then decides it’s time to end the fun and plays an intensely swinging run that is higher than Dizzy with a big bright sound. Then he goes even higher. He swings even harder, his tone is even fuller, and he ends with a shriek. I’m sure everyone in the studio applauded, and Dizzy hugged Roy. Joy was in the room. That was what Roy “Little Jazz” Eldridge was supposed to do—outplay you, and as long as he did, all was right with jazz.

In 1975, Jazz Maturity was a throwback to a time when all was indeed right with jazz. Black culture in America had changed and turned away from jazz to R&B and funk. Jazz changed with it, and as the music coped with a diminishing audience, it turned to young white rock fans for sustenance, abandoning standard tunes, minimizing blues and swing while incorporating the rhythms, electricity, volume, and intensity of rock. The devil is always in the definitions, and one can argue endlessly whether the new “fusion jazz” and the other jazz with hyphens were really “jazz,” but they were definitely not the music of Gillespie and Eldridge and the many others who were their peers and had come to their own jazz maturity in a Black culture that had created Swing music and nurtured bop. The jazz they all played was a personal and cultural expression, a high art of sophisticated harmony and melody, and also a folk music suffused with the foundation of Black music in America—the blues and swing.

Jazz Maturity was one of the last great expressions of that jazz. Eldridge only recorded three more albums, suffered a heart attack in 1980, and stopped playing trumpet. Gillespie became a media icon, which was well deserved, and continued to play until shortly before his death, usually with much younger musicians, on occasions brilliantly, though embouchure problems limited their frequency. He never made another album like Jazz Maturity. No one else will. That jazz is gone.

Jazz Maturity was recorded by the great engineer Bob Simpson at RCA studios in New York. It is a superb stereo, natural club-like recording of the band with a wide soundstage. Gillespie and Peterson are on the left, and Eldridge on the right, with bass and drums in the middle. The recording of Ray Brown’s bass is wonderful—deep and very melodic. All the overtones hang in the air and decay naturally. His dynamic attack, essential to his incredible swing, is accurately captured. The trumpets are easily distinguished because Simpson recorded them with such accuracy and wide dynamic range. Eldridge’s wails, shrieks, and growls never blare. Gillespie’s darker, rounder sound is beautifully captured. Peterson’s piano virtuosity is masterfully recorded. The two hands are clearly heard playing separate lines, but the piano doesn’t have that unrealistic “giant keyboard” sound when he solos. Roker’s drums have great dynamic range, and the individual drums and cymbals can be distinguished. The tonal balance of the recording is warm and accurate, with a wide tactile midrange. I say “wide” because, on reference quality recordings, the midrange seems wider because the bass and treble are so much more extended. There’s lots of “air” and low level detail, and the listener hears the musicians playing in a room. It was an exciting session, and Simpson captured the emotion in the studio.

Pablo pressings were generally very good, and play very well if clean. U.S. original 1978 copies of Jazz Maturity can be purchased for $10 or less. Musically and sonically, the album is a near masterpiece and a bargain at that price. The album has never been reissued on LP in the U.S. There were CDs issued in the mid-90s that I have not heard.

I own almost all the Pablo albums, so I’ll spread the word that Pablo is among the great jazz labels and very underrated by audiophiles. Granz believed in good sound-- a natural, 50s style sound and usually hired the right engineers to achieve it. The Pablo catalog is full of little known audiophile classics, and the music is near uniformly very good. Almost all the Pablo LPs are available for $10 or less--most less.

Copyright by Joseph W. Washek 2023 and all rights are reserved.

.png)