And You’ll Never Hear Surf Music Again: Jimi Hendrix On Record

From the archives: Jimi Hendrix's discography... on vinyl!

(This feature originally appeared as a cover story in Issue 5/6, Winter 1995/96.)

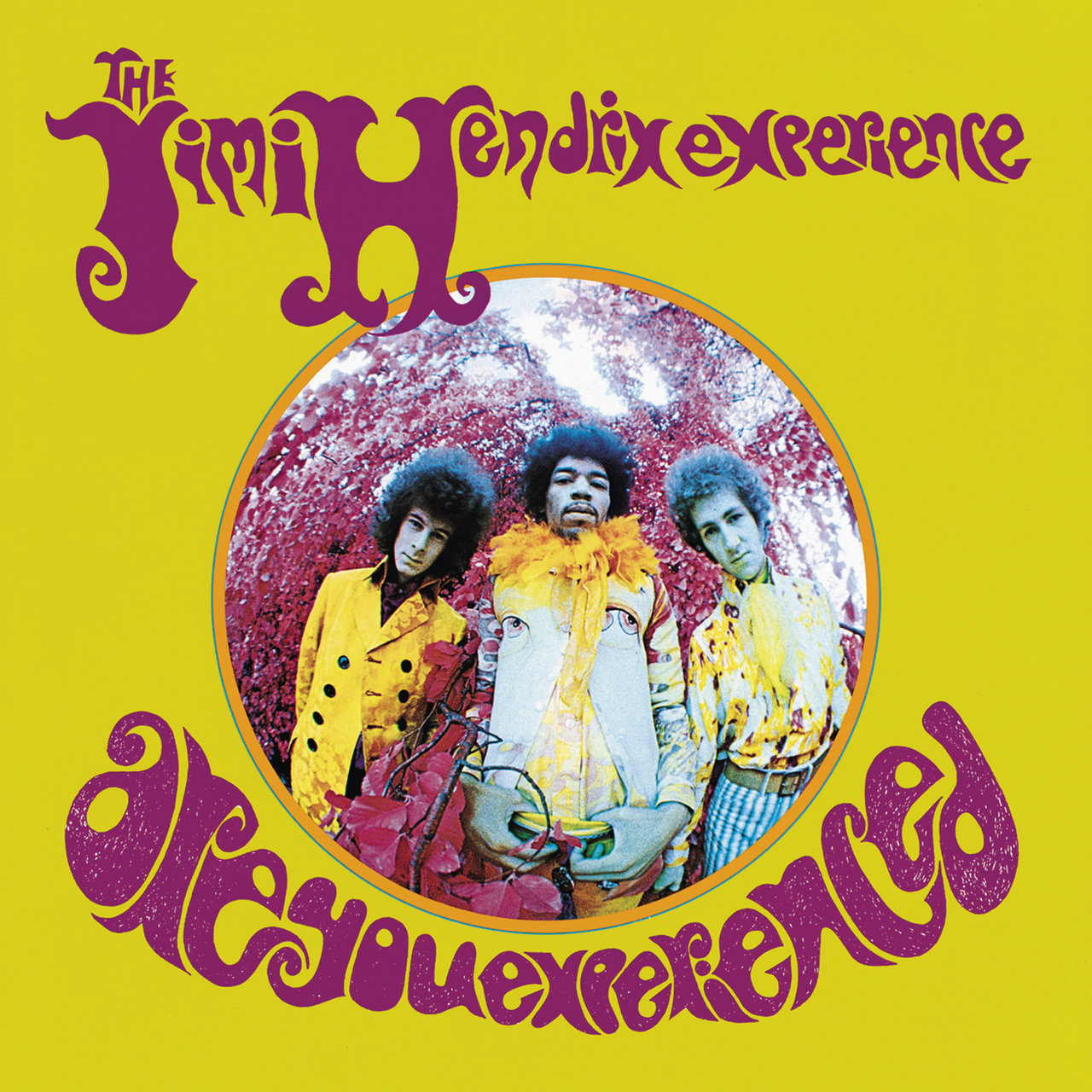

Contrary to prevailing opinion circa 1967, Jimi Hendrix did not arrive from outer space. He was from Seattle, which probably had a greater effect on his music than if he had come from another planet. For those of us old enough to remember hearing Are You Experienced? when it was first issued in America, summer of 1967, Hendrix was some Black English cat who’d taken psychedelia from the inner mind to outer space.

In the summer of 1967, without the benefit of MTV or a firmly established “underground” press, names traveled through the streets and college dormitories, attached at best to rumors and scattershot facts. When the buzz you heard somewhere matched a name on a record, you bought it. In the case of Jimi Hendrix, what filtered through the “underground” grapevine (“hempline” would be more like it) was his show stopping performance at the Monterey Pop Festival.

With the release of Are You Experienced?, what American record buyers saw first was a dated concept: a fish eye lense photo which looked like a rip-off of The Byrds’ first album cover—only filled with more outrageous looking characters.

Between these two frizzy-haired, English blokes was Hendrix, looking just plain different. Forget the orange frilly collar, or even Hendrix’s exotic facial structure; the vibe Hendrix radiated was so intense, a still photo was sufficient to make the point. This guy was different.

Hendrix was clearly Black, but he didn’t look like a Temptation—or any other Black musician who’d crossed the mid-60s musical color barrier. Most of them wore suits. Hendrix didn’t dress or look “soulful;” he looked more like a clown prince from another world.

The high contrast, back-lit, black and white back cover photo made bassist Noel Redding (Hendrix referred to him as “Bob Dylan’s grandmother”) and drummer Mitch Mitchell look more conventional—two guys with long hair posing “heavy”—but Hendrix straight on exuded an even greater otherworldly appearance and feel. The look in his eyes was distant and somewhat aggressive, yet vulnerable, and even sad.

What struck this college senior upon playing Are You Experienced? for the first time—and I remember the where and when as if it was yesterday—was the over the top humor behind “heavy” songs like “Purple Haze,” “Fire” and “Foxey Lady.” The nod and wink of “Foxey Lady” atomized the kind of repellent salacious baggage such songs often carry. Other songs revealed a vivid imagination and an ability to project three-dimensional visual images which equalled or surpassed the lyrical abilities of the best songwriters of the day.

I also remember removing the record from the sleeve to find the totally incongruous and old-fashioned-looking Reprise “steamboat” label, which brought the whole outerspace enterprise crashing back to earth with images of Frank Sinatra and Trini Lopez. Oh well.

Wait Until Tomorrow

25 years after his accidental death from a bad reaction to sleeping pills—not from a “drug overdose,” though Hendrix had dabbled and gotten burned—Jimi Hendrix the person remains an enigma; his music, his guitar playing and yes, even his singing for which he continually apologized, continue to speak to those who were first moved, and to new generations of music fans and musicians.

While it is simplistic to lump Hendrix in with other “Black rockers” like Chuck Berry, or Prince (actually of Black, Hispanic and Italian heritage), there is a connection: like Berry born in St. Louis and Prince, from Minneapolis, Hendrix also hailed from a town with a small Black community.

As with Chuck Berry who found success blending blues and jazz with 1950s teenage themes, Hendrix did likewise a decade later (hard to believe only ten years passed between 1957 and 1967) with psychedelia and the “Summer Of Love”’s emerging underground “hippie” scene. Berry’s diction was clear, his inflections raceless; Hendrix’s vocalizing, while stamped with a bluesy subtext, rocked.

In the indispensable book Hendrix: Setting The Record Straight by John McDermott with Eddie Kramer, Hendrix is quoted as saying “I liked Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Muddy Waters, Elmore James (and) B.B. King.” Can’t go wrong there.

Like his music, Hendrix seemed to move effortlessly, almost seamlessly, between white and Black cultures. Indeed, the liner notes to the MCA CD Blues (MCAD 11060) claim the Hendrix family roots combine Irish, Indian and African ancestry. Nonetheless, there was dissonance, and Hendrix paid a personal price for bridging the cultural gap between the races. His decision to play with two white musicians angered some in the Black community.

After a jumping incident supposedly led to his honorable discharge from the Army’s Airborne division, Hendrix commenced his musical career, moving to Nashville and joining up with his Army buddy and bandmate Billy Cox.

Hendrix led a Forrest Gump-like musical existence: while visiting relatives in Macon, Georgia, the then-13-year old aspiring musician chanced to meet Johnny Jenkins, an older kid who went on to become Otis Redding’s guitarist. After leaving Nashville, Hendrix ended up backing everyone from Little Richard to B.B. King to Jackie Wilson to Little Richard to Sam Cooke and The Isley Brothers. He even put in time with Joey Dee and The Starlighters. There was a chance meeting in East St. Louis with fellow lefty Albert King, where Hendrix was putting in time with an abusive Ike Turner.

But Hendrix wasn’t born to be a backup R&B guitarist—his musical and visual styles were too flashy. Eventually he quit playing the “chitlin circuit” and moved to New York, where he won Amateur Night at the Apollo first try.

The story of how Hendrix lived a life uptown in Harlem and downtown in Greenwich Village, how he formed his own band and played the Village scene influenced by the words and music of Bob Dylan, how he was “discovered” by Linda Keith—Keith Richards’ girlfriend at the time—who brought him to the attention of Chas Chandler (bassist for The Animals, who was looking to quit the group and become a producer), how Chandler convinced Hendrix to disband the group (which included soon-to-be Spirit lead guitarist Randy California) and move to London is skillfully recounted in McDermott’s book.

Chandler believed. He saw something in Hendrix which others hadn’t (among them Andrew Loog Oldham whom Linda Keith had dragged down to the Village’s Cafe Wha? where Hendrix and his group Jimmy James and The Blue Flames were playing); something he thought could be translated into pop stardom.

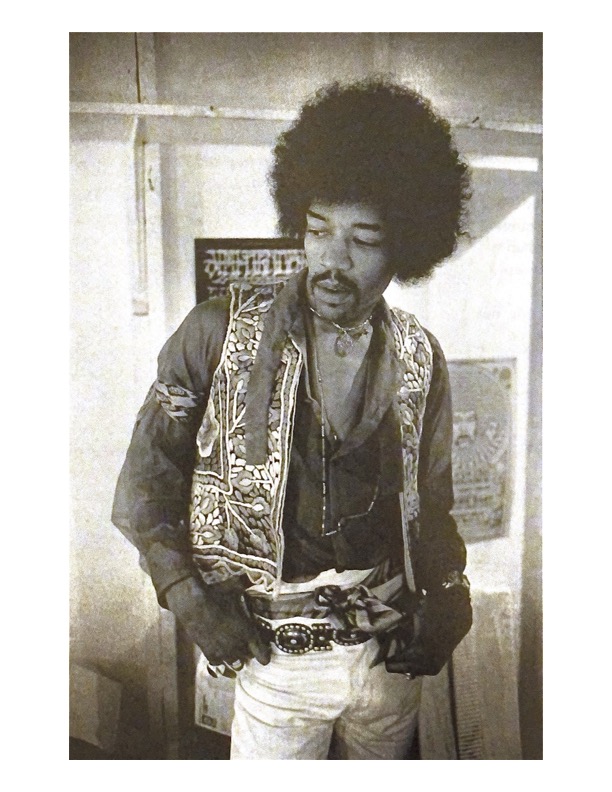

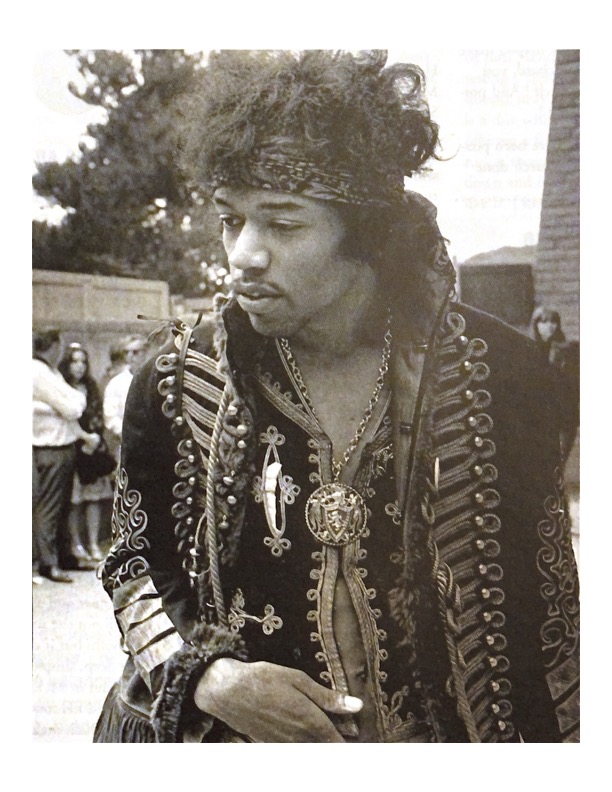

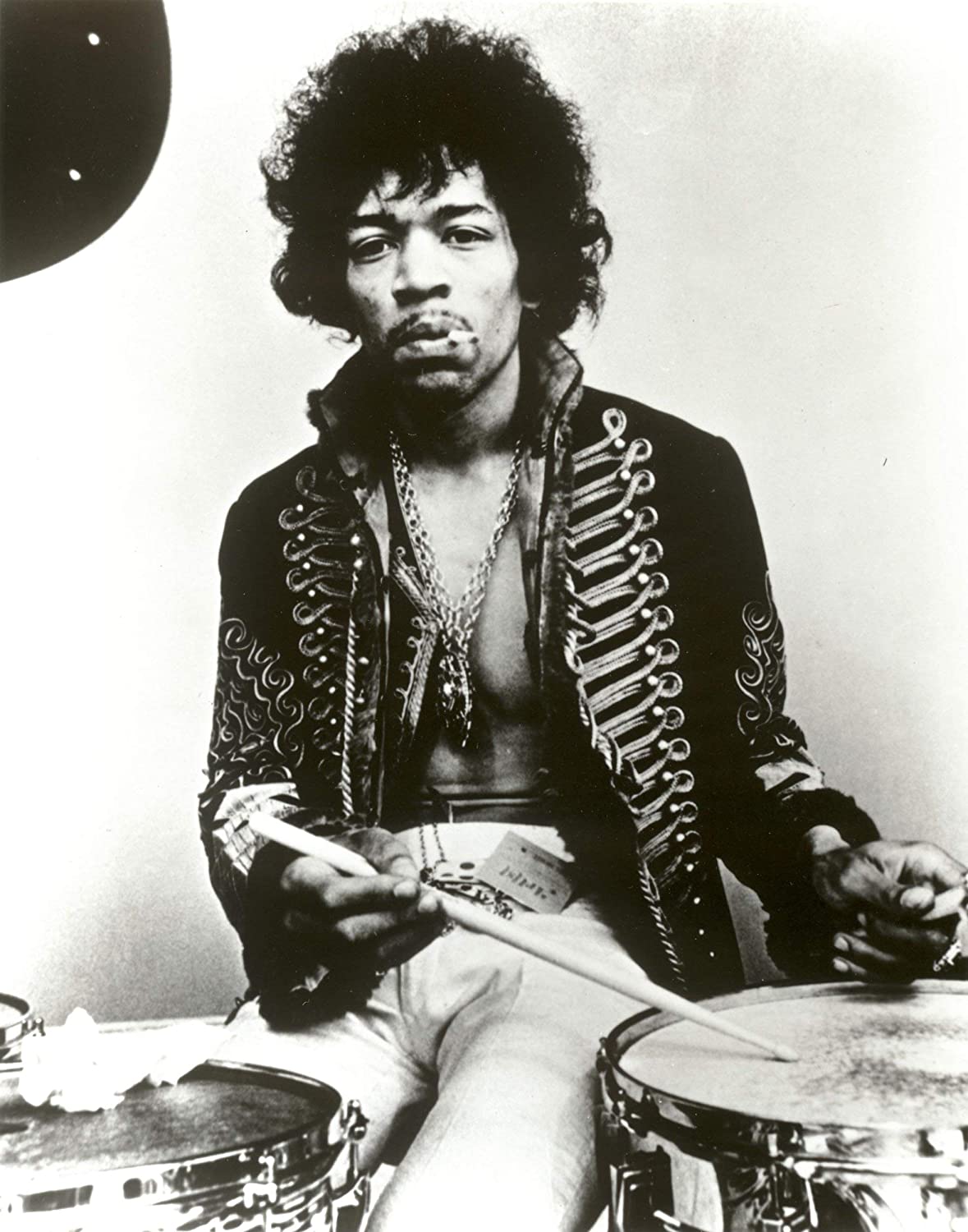

Jimi backstage at Winterland, 1968 ©Jim Marshall

Jimi backstage at Winterland, 1968 ©Jim Marshall

Even as you read the nuts and bolts of how the Experience was named and how Hendrix picked his bandmates, of the media manipulation used to help ensure Hendrix’s chart success, even as you read, in McDermott’s second and equally indispensable book, Jimi Hendrix Sessions written with Billy Cox and Eddie Kramer, how the songs were written and the records painstakingly created, track by track, meticulous as it is, it doesn’t begin to provide a satisfactory explanation of who Jimi Hendrix was or where this music really came from.

Nor are the answers to be found in the somewhat far fetched theories contained in the nonetheless fascinating liner notes to MCA's Blues CD, wherein annotator Michael Fairchild writes that Hendrix was “supernaturally transformed” into a “voodoo chile” while visiting Georgia as a teen. The questions are in the music and so are the answers.

Hendrix On Record

Jimi Hendrix released but four studio albums in his short meteoric recording career—and the final one, The Cry Of Love, was issued posthumously, completed and compiled after his death. The remainder of the catalog are pre-Experience sideman sessions, reissues, compilations of unissued tracks, live performances, bootlegs and “jams.”

It was the custom in mid-60s Britain to not include singles on albums. So the track selections on the British and American Are You Experienced? differ—as do the album covers. Paving the way for Hendrix’s album debut in England were the singles: “Hey Joe”/“Stone Free” (Polydor 56139) released 12/16/66, “Purple Haze”/“51st Anniversary” (Track 604 001) issued 3/17/67 and “The Wind Cries Mary”/“Highway Chile” (Track 604 004) released 5/5/67.

A week later came Are You Experienced (Track 612-001) containing “Foxey Lady,” “Manic Depression,” “Red House,” “Can You See Me?”, “Love Or Confusion,” “I Don’t Live Today,” “May This Be Love,” “Fire,” “Third Stone From The Sun,” “Remember,” and “Are You Experienced.”

UK Track Records "Are You Experienced"

UK Track Records "Are You Experienced"

Holed up with Chandler and his wife in their apartment, Hendrix toyed with the bits and pieces of musical ideas he’d been developing over the years. He spent his spare time reading Chandler’s collection of science fiction books. Working on a tight budget, Chandler booked studio time only after ideas had been worked out, and Hendrix was ready to record them. “Hey Joe,” the first song Chandler had heard Hendrix perform at Cafe Wha?, was the initial project.

Incredibly, the week before seeing Hendrix do the song at Cafe Wha?, Chandler had heard Tim Rose’s slow, folky version. Convinced of the song’s commercial potential, he vowed that upon returning to London he’d find an artist to record “Hey Joe.” With Hendrix answering the call, the song peaked at number six—not bad for a first effort.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience was the original “band on the run” in those early days. Because Hendrix didn’t have a recording contract, sessions were short—depending on how much money Chandler could scrape together. Chandler carried the “Hey Joe” basic backing tracks from studio to studio, overdubbing additional instrumental parts and backup and lead vocals until he had a finished master.

Chandler told McDermott that after hearing “Hey Joe,” Decca’s Dick Rowe (who’d turned down The Beatles), “...looked at me as if I was mad.” Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, managers of The Who, had just formed Track Records when Chandler invited them to see Hendrix live. They saw, they signed—on a placemat.

Enter Eddie Kramer

Unhappy with the sound at DeLane Lea, the studio used for “Hey Joe,” and after a financial dispute at CBS Studios, Chandler, at the suggestion of Bill Wyman and Brian Jones, brought The Jimi Hendrix Experience to Olympic, a studio long revered by audiophiles for producing some of the finest sounding recordings during British rock’s “golden age.” On February 3, 1967 Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Kramer began a working relationship which lasted until Hendrix’s death—and beyond.

As with engineer/producer Roy Halee and Simon & Garfunkel, Kramer’s involvement with Hendrix meant that artistic visions could be translated into sonic realities. Once Kramer got involved, technically complex songs like “Are You Experienced” with its backwards guitar and rhythm parts, and “Third Stone From The Sun” became feasible, even with the limited technology of the day. Hendrix had found a technical partner, a translator.

Kramer used two of the four available tracks for Mitch Mitchell’s drums, recording them in stereo. The two remaining tracks were for Noel Redding’s bass and Hendrix’s rhythm guitar. The four tracks would then be mixed down to two tracks of another four-track recorder, leaving two more tracks for vocals, lead guitar and whatever else was to be added. This recording method was highly unusual at the time, but it meant that the basic tracks were down, leaving Hendrix much more freedom to experiment.

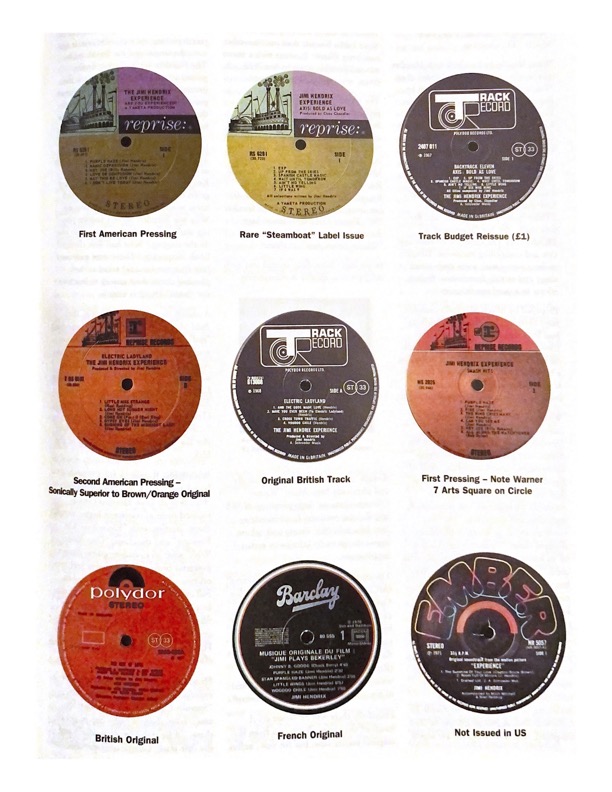

A Jimi Hendrix labelography (mid-1990s)

A Jimi Hendrix labelography (mid-1990s)

It also meant that the basic tracks were down a generation from the overdubs, and that while there was a big, live stereo drum sound in the center fill, vocals and leads were pushed off to the sides in the stereo mix. No one will ever confuse the Are You Experienced? album in any of its incarnations with an audiophile recording.

Still some tracks pack a pretty good sonic wallop, with outstanding deep bass, good ring to cymbals and tremendous presence to Hendrix’s lead vocals. An original British Track pressing was not available for this story. How many times had I seen it in the bins back in 1967/8 and passed because it didn't contain the “hits”? Don't ask! According to McDermott’s book, Eddie Kramer and Chas Chandler mixed, banded and mastered the album in April 1967, with Kramer cutting lacquers the next morning.

Despite the less than stellar track selection, the original British pressing (by Polydor) must be considered definitive. The American Are You Experienced? (Reprise RS 6261) issued August 23, 1967 (almost two months after The Jimi Hendrix Experience had blown away the Monterey Pop Festival crowd), contains the hits: “Purple Haze,” “Hey Joe,” and “The Wind Cries Mary” in place of “Red House,” “Can You See Me?” and “Remember.” Reprise added the hits, and deleted the roots: the pure blues of “Red House,” and the choogling soul of “Remember,” with its “Can’t Help Myself” chording.

The U.S. Reprise "Are You Experienced" cover

The U.S. Reprise "Are You Experienced" cover

While Reprise had no luck with Hendrix as a singles artist (“Hey Joe” didn't chart, “Purple Haze” got to #65), helped by airplay on “underground” FM stations like WNEW in New York, and San Francisco’s KSAN, Are You Experienced? was a big hit—Hendrix’s most popular album at the time of his death.

With rockers like “Foxey Lady” and “Fire,” angry stingers like “Manic Depression” and “I Don’t Live Today,” and space trips like “Purple Haze,” “Third Stone From The Sun” and the title track, Are You Experienced? is Hendrix and The Experience’s most concise and compelling statement. Hendrix makes contact with some deep seated anger and earthly frustrations, finding release in spaced out fantasies.

Propelled by Mitch Mitchell’s complex, jazzy rhythms, and Redding’s “walking” basslines suggested by Hendrix, the trio’s power cuts through even the thickest layers of studio gimmickry, delivering a blend of blues, rock, jazz and electronic effects which sounded like an instant shortcut to a new musical world.

While the British Are You Experienced jacket included a straightforward Hendrix bio which alluded both to his Seattle birthplace and his “soul music” background, as well as smiling shots of Redding and Mitchell (looking a great deal like a young Ray Davies), the American presentation was purposefully menacing and mysterious. The liner notes are either unintentionally funny, or planned camp: “Be forewarned. Used to be an experience meant making you a bit older. This one makes you wider…You hear with new ears, after being experienced….” Never mind that most first time listeners found those words to be true!

The first American “steamboat” label pressing of Are You Experienced? was mastered at Columbia Records’ Hollywood studios since Warner Brothers at that time did not have its own facility. According to Goldmine’s Price Guide To Collectible Records Fourth Edition by Neil Umphred, near mint originals are worth $40 in stereo and $100 in mono. Since Eddie Kramer does not remember supplying Warner Brothers with a mono mix, it’s possible a two-to-one “fold down” was produced by Columbia.

The original is thick and very well pressed—also probably by Columbia. Second issue Reprise labels were orange and brown with the Warner-Seven Arts “W” attached to the Reprise logo. After the Seven Arts deal was dissolved, the label shifted to all orange with “Reprise Records, a Division of Warner Bros. Records, Inc.” on the bottom. Mid to late 70s pressings show the familiar “W” Warner Communications logo, though jackets continued to say “Warner-Seven Arts” on them.

In my experience, first, second and even third pressing quality is outstanding, though “steamboat” firsts are sonically and physically best. Most “Warner Communications” logo pressings of WB and Reprise products from Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and others sound distinctly inferior to earlier incarnations.

The current CD of Are You Experienced? (MCA MCAD-10893), mastered by Joe Gastwirt, offers outstanding dynamics, bass extension, focus and high frequency clarity. The only vinyl I’ve heard which betters the CD in quality is The Essential Jimi Hendrix Volume Two (Reprise HS 2293) issued in 1979, which contains an outstanding transfer of five tracks from Are You Experienced?.

Hopefully there will be future vinyl issues of the entire album, cut from the original master tape, but for now, unless you’re absolutely anti-digital, the CD is worth picking up. The Hendrix family, having finally gained control of the masters, is in the process of label shopping. For the future prospects of vinyl Hendrix issues, read the interview with Eddie Kramer in this issue.

Around Christmas 1967, Capitol released Get That Feeling (ST 2856), older recordings of Hendrix backing soul man Curtis Knight, with the new underground star given top billing. It was a ripoff which naive record buyers never saw coming. Why was Hendrix all of a sudden playing soul music and letting someone else do the singing? Why had Jimi changed labels so quickly? These were questions fans (this fan for one) asked as they plunked down their money to listen to the “latest” Hendrix album.

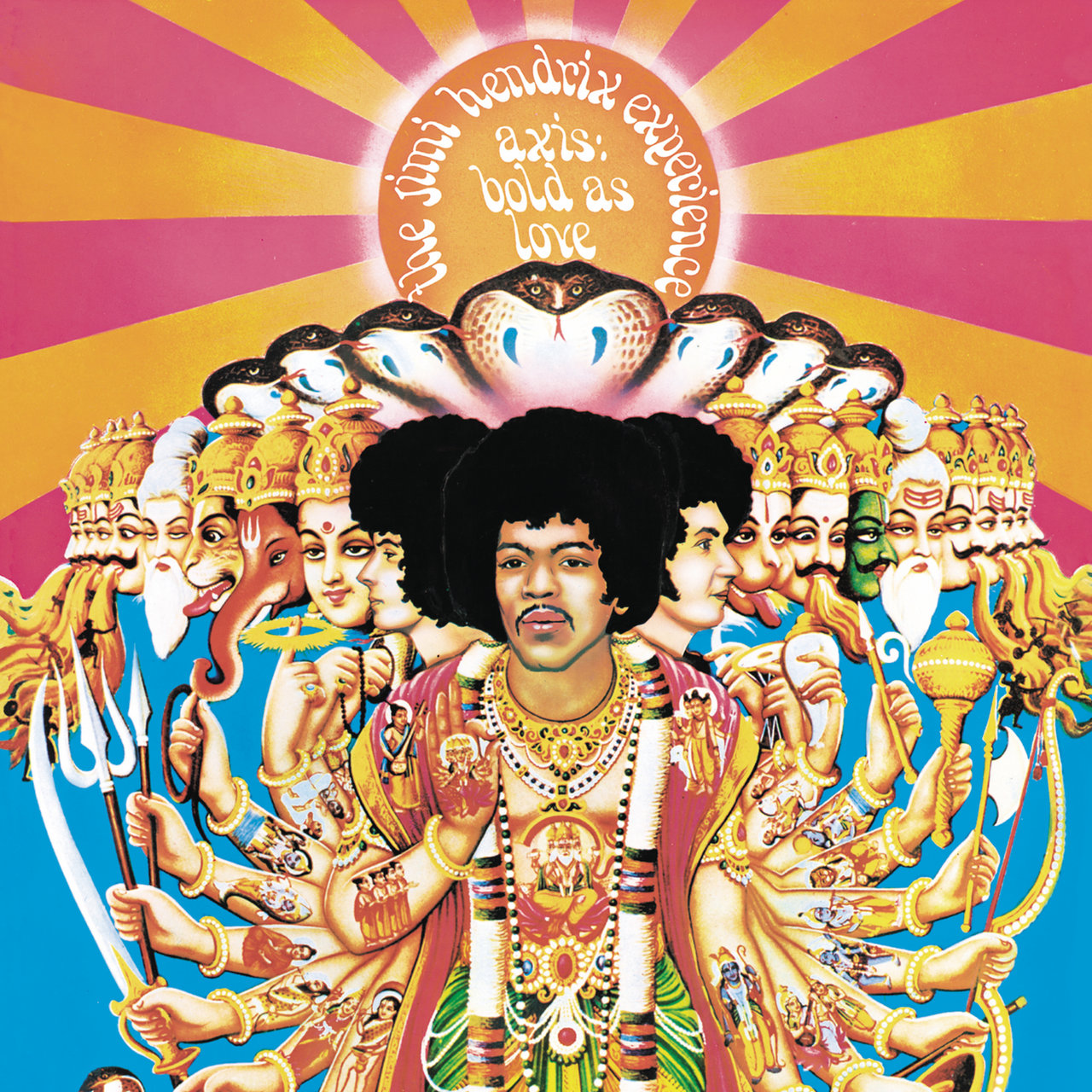

Axis: Bold As Love

Axis: Bold As Love

A month later, in January 1968, Axis: Bold As Love (Reprise RS 6281), the next “real” Jimi Hendrix Experience album, was released in America. Meanwhile, in August 1967, before Axis was issued stateside, “The Burning Of The Midnight Lamp” which eventually appeared on Electric Ladyland was issued as a single (Track 604 007) in the UK. In fact, “Burning” was issued there before Are You Experienced? was released in the US.

With Eddie Kramer at the Olympic board and Chas Chandler producing, Axis: Bold As Love—Hendrix’s most focused musical statement—took shape, beginning with “You’ve Got Me Floating” and the classic “One Rainy Wish” with its cascading guitar figures, powerful bridge (“I have never laid eyes on you…”) and kaleidoscopic visuals. Fall 1967 saw the completion of the love-desperate “Wait Until Tomorrow,” filled with Romeo and Juliet imagery, and the poignant “Little Wing,” one of Hendrix’s most fully realized songwriting efforts.

Hendrix’s lyrics reached new levels of expressiveness on Axis. Songs like “Spanish Castle Magic” (“It’s very far away, takes about a half a day to get to there/If we travel by dragonfly”) and the title track created unforgettable visuals in the stoned mind’s eyes of listeners, capped by the psychedelic stereo phasing (a first, created by engineer George Chkiantz) which ends the album. That trick, combined with Hendrix’s wirey, insistent guitar solo and harpsichord overdub, came as close to describing the sensation of drug-induced ecstasy as any piece of music created during that era. The phasing/flanging effect creates behind the head “surround sound” from two channels. The album’s finale, “Bold As Love,” with its slinky, syncopated vocal, slow burning musical buildup, screaming, controlled guitar solo, punchy rhythm guitar line and psychedelic payoff, epitomized The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

According to McDermott in Jimi Hendrix Sessions, on Halloween night 1967 Hendrix left the studio with the mixes for side one of Axis and ended up leaving them in a taxicab. They disappeared. The next day Kramer and Chandler feverishly remixed the side, but “If 6 Was 9,” Hendrix’s take on alienation and being the “other” (“White collared conservative flashing down the street/Pointing their plastic finger at me”) proved impossible to recreate. Noel Redding’s three-inch 7 1/2 IPS reel to reel copy (after being ironed flat) was used as the master. So that’s why that track sounds so noisy and distant. Actually, given the source, the sound is surprisingly good. In fact, it almost sounds planned.

Axis: Bold As Love (Track Records 613 003), with its dramatic retouched Hindu icon cover, was released in the UK on Friday, December 1, 1967 and in the United States shortly thereafter (Reprise RS 6281) on Wednesday, January 10, 1968, the date delayed to let the air clear from the stench of Capitol’s Curtis Knight release. About the cover, which Hendrix had nothing whatsoever to do with choosing, he’s reported to have said “maybe we should have an American Indian.”

The original British issue featured a laminated gatefold sleeve and inner LP pocket, with a dramatic double truck black and white photo of Redding, Hendrix and Mitchell inside. Aside from the track listing on the upper left hand corner of the photo the only other credits on the album read “This is the second album from the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Jimi Hendrix is the man in the middle with the curly hair and the broken face. Noel Redding is the man on the left and Mitch Mitchell is the man on the right. Jimi Hendrix writes his own music and almost sings it, he also plays guitar.” The line about “almost” singing may be someone’s idea of cute, but it is dead wrong.

In America, Reprise canned the original inner photo, substituting a much smaller white and black shot surrounded by the lyrics in white against a black background. Production, engineering and other credits were also included, as well as a misspelling of the legal arm of the enterprise, “Yameta Co. Ltd,” which was spelled “Yaneta.”

In one of the stupider moves in this writer’s record collecting history, I traded in my original British Track pressing for a Japanese reissue (MPF 1076). Oy vey! The original Track offered outstanding sonics, as you might expect from a Kramer/Olympic production, with buttery smooth, ringing cymbals, a crackling, well defined snare and decent kick to the bass drum. Redding’s bass (sometimes overridden by Hendrix) featured outstanding articulation and low frequency extension.

Hendrix’s vocals, centered in front of Mitchell’s stereo drum kit on most cuts, were smooth, extended and three-dimensional while his guitars were assigned hard left/right positions on the soundstage. An outstanding sounding recording and pressing.

The original American pressing issued for a very short time on the original pink and yellow “steamboat” label ($40 Goldmine) offers superb sound, close to what I remember the British pressing sounding like. Does my sonic memory survive the eleven years since I traded the original? Bet yer ass it does! Second pressings (brown and tan) are probably equally good sounding. The album was issued in mono for the blink of an eye and then discontinued as the record industry went all stereo to kill the space wasting dual inventory. Thus, the Goldmine guide values a mint, rare original mono pressing at $1000!

As for the Japanese pressing, it is well packaged, with the original British artwork, and as usual extremely well pressed but bass is seriously rolled off, the top is tweaked up and the beginning of “You Got Me Floating” is chopped off, so the track starts with the drum lick instead of the studio business you’ll hear on original pressings and on the CD reissue.

But don’t blame the Japanese for that! In the early 70s Track issued a series of ridiculously cheap budget LPs called “Backtrack,” some combining artists (there’s a Hendrix/Who compilation for example) and some reissuing whole LPs, one of which was Axis: Bold As Love (Backtrack 2407 011). The beginning of “You Got Me Floating” is chopped off there too, so obviously Polydor Japan was supplied with a chopped copy of the master. Otherwise, the Backtrack reissue is well pressed on thick vinyl and offers fine sound, though somewhat brighter and harder on top than the original. When I was in England last year, original copies of Axis: Bold As Love were nowhere to be found, but the plain green jacket Backtrack issue was plentiful for about $12 USD.

The CD issue (MCAD-10894) offers outstanding bass extension and dynamics, but as usual, the better the original recording and pressing, the worse the CD sounds, no matter how carefully it was transferred. The CD is grainy and harsh on top and flat-sounding compared to the original American pressing, with rubbery bass articulation despite the extension and dynamics on bottom. Still, if you can’t find an original, the CD with its outstanding annotation is worth picking up until we get Axis on audiophile vinyl!

At Olympic Studios towards the end of December 1967, Hendrix began recording tracks for what would become Electric Ladyland. “Crosstown Traffic” came first, and yes, according to the Jimi Hendrix Sessions book, that is Hendrix on kazoo doubling his guitar.

In January 1968, Hendrix continued sessions for the double LP set, with “All Along The Watchtower,” aided by Traffic’s Dave Mason on 12-string acoustic. According to McDermott in Sessions, Mason “...earned the brunt of Hendrix’s reprimands as he struggled to master the song’s chord changes.” Odd, since the song was basically three simple chords.

A US tour in winter 1968 suspended recording, but in the spring sessions resumed at the Record Plant in New York, which had a new Scully 12-track recorder and Eddie Kramer who’d left Olympic to join the new facility and Jimi Hendrix.

In April 1968, Track Records issued its version of Smash Hits (Track 613 004) which contained the singles not previously issued on LP and cuts from Are You Experienced? Meanwhile, friction between Hendrix and Chas Chandler grew, out of Hendrix’s desire to gain control of his work coupled with his increasing drug use which led to marathon, unproductive sessions (ie: 41 takes of “Gypsy Eyes,” none of which became masters) and the presence of the usual bloodsuckers and leeches hanging around the studio.

Also visiting the studio one night were Jack Cassady and Stevie Winwood: thus was born the spontaneous “Voodoo Chile” live jam which Kramer had to mic on the fly. That the “party” sounds were overdubbed later is no surprise: the “walla” (background chatter) sounded hollow and false back in 1968 when the record was first issued. While Hendrix was a great musician, he was less convincing as an actor.

Despite the hangers on, drug use, and friction in the band, Hendrix and company laid down the basic tracks for “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be),” perhaps the finest track on the record and one of the group’s most ambitious compositions.

By May, according to McDermott, Chandler, no longer able to exercise control over the sessions and fed up with Hendrix’s lack of focus and ever expanding studio entourage, walked out. Mitchell and Redding were also becoming increasingly disenchanted. Mixing and recording continued throughout the apocalyptic summer of 1968: Robert Kennedy was assassinated, the Chicago police rioted at the Democratic National Convention, LA burned, and Hendrix and Eddie Kramer completed Electric Ladyland.

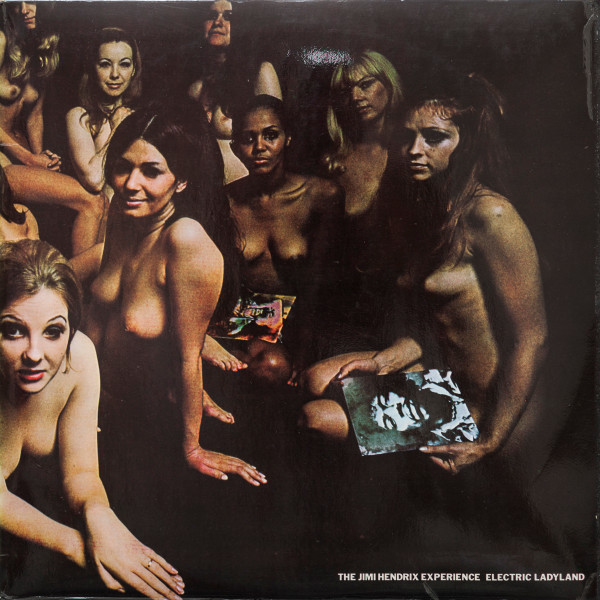

UK Track Records original cover "Electric Ladyland", not to Jimi's liking

UK Track Records original cover "Electric Ladyland", not to Jimi's liking

Released first in the United States on October 16, 1968, Electric Ladyland reached number one, though Hendrix was disappointed with the cover art and the sound, as were audiophiles at the time: all three of them. Hendrix’s complaints were the same as mine: the sound was muddy and bass heavy. Compared to Axis: Bold As Love, Electric Ladyland lacked sparkle, clarity and focus. Much of it sounded distant and down several generations, though it wasn’t.

Apparently Hendrix sent along detailed instructions with the artwork and mastertape, telling Warner Brothers how he wanted the cover laid out and how the LP was to be mastered. Realizing that the mastering engineers would find a great deal of out-of-phase information, which they might attempt to “fix,” a note telling them to leave it alone was included and ignored.

According to Lee Herschberg at Warner Brothers, as with Axis the mastering and cutting of Electric Ladyland were handled by Columbia Records. Contrary to popular opinion, the British “naked ladies” cover is not the original cover which Warner Brothers censored. In fact, while the American cover was not what Hendrix had wanted, it was closer to his concept than the British cover which incensed him.

The British pressing of Electric Ladyland (Track Records 613 008/9) was released nine days after the American issue. This time, while the source must have been a copy of the master, the cutting engineers left the out-of-phase information out of phase. So where three-dimensional effects are intended, as on the opening track “...And The Gods Made Love,” sound swirls around your head as if you were listening on a surround sound system. The British Track original, despite the unauthorized cover, is the vinyl issue to have. It features deep, tight bass, and outstanding overall clarity, though the sound on many tracks lacks the shimmer and focus of Axis.

Forget the Japanese pressing which is rolled on bottom and thin on top. A second American pressing I have on hand (all tan label) cleans up the mud of the original pressing, but it sounds spatially flat compared to the British original, and not nearly as focused in the bass, though extension is decent.

The MCA CD (MCAD-10895) is remarkably true to the original British pressing (taking into account what is wrong with 16bit digital), though it is somewhat laid back at the very top and not nearly as spacious or detailed. Still, if you can’t find a British Track original, the MCA CD is worth picking up until the vinyl is reissued.

If Axis: Bold As Love is a living color fairy tale, Electric Ladyland, recorded over a lengthy period of time in both England and America, is a dark, sprawling work, reflecting the increasingly complex inner and outer world in which Hendrix found himself. More jazzy and stretched out, Electric Ladyland features long jams, straight ahead soul (Earl King’s “Come On”), experimental soundscapes (“1983… A Merman I Should Turn to Be”), blues, hard charging rock (“Crosstown Traffic”), and of course the definitive cover of “All Along The Watchtower.”

The almost seamless mixture of music and effects proves that the production was part of Hendrix’s vision, not gimmickry tacked on as an afterthought to “spice up” the record. Hendrix’s final statement is one worth savoring again and again for its intrinsic richness, and for its suggestion of what might have been had Hendrix lived.

With Chandler, Redding and Mitchell slowly drifting away, Hendrix found himself once again in control of his own destiny. He began producing albums for Eire Apparent, Cat Mother & the All Night Newsboys, and his friend Buddy Miles. Reunited in England for a gig at the Royal Albert Hall, the band attempted to record at Olympic once more, but there was no spark left.

Lots of jams on both sides of the ocean followed including one supposedly “legendary” session with jazz guitarist John McLaughlin and Buddy Miles on drums which has never been released. I have a clean cassette copy, probably a copy of a copy (don't ask!) and aside from the curiosity factor it’s not something you’d want to hear a second time, though there are some pretty hot licks. Hearing McLaughlin’s pristine lines clashing and sometimes meshing with Hendrix’s machine gun blues is interesting, but McLaughlin had to feel straightjacketed playing against Miles’ stiff timekeeping.

Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop Festival, 1967 © Jim Marshall

Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop Festival, 1967 © Jim Marshall

While Hendrix toyed with Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox in the studio, he returned to the San Diego Sports Arena stage with Mitchell and Redding in May of 1969. Tracks recorded at the concert eventually found their way onto various live recordings issued during the mid-1970s.

A few weeks before Woodstock, on July 30, 1969, Reprise, hungry for a follow up to Electric Ladyland, issued its own version of Smash Hits (Reprise MS 2025), including the four tracks cut from the American Are You Experienced? plus others from the debut and standouts from Electric Ladyland. Axis was not represented.

Smash Hits is a curious, unsatisfying collection, though after Hendrix’s death it became his biggest seller, probably because it had the word “hits” in the title. Sonically it’s mediocre too, on the original brown/tan Reprise-Seven Arts logo pressing and on subsequent versions. All of the tracks sound better elsewhere. Mint copies with the poster are valued at $60 in Goldmine’s record guide.

I was tripping and/or sleeping through most of Hendrix’s Woodstock performance backed by Gypsy Sun and Rainbows, but what I’ve heard of it was pretty sloppy save for his rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Hendrix’s recording experiments with Gypsy Sun and Rainbows (Billy Cox on bass, guitarist Larry Lee, percussionists Jerry Valez and Juma Sultan, and Mitch Mitchell on drums) produced little of value. Meanwhile construction of Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village had begun. The expanded group broke up in fall 1969, with Mitchell splitting for England.

Due to contractual obligations from a deal Hendrix had signed with producer Ed Chalpin before Chas Chandler’s involvement, Hendrix owed an album to Chalpin and Capitol. The Band of Gypsies was formed later that fall.

Entertainers will tell you that performing on New Year’s Eve is as close to the toilet as it gets. Band Of Gypsies’ live New Year’s Eve 1969 performance at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East wasn’t a disaster, but it wasn’t stellar either. The band was under rehearsed, and as Buddy Miles is quoted as saying in McDermott’s book, “Overall, the feeling was, ‘What the heck, the album doesn’t belong to us anyway.’”

A heavily edited six-track set became the record Hendrix owed Capitol, which released Band of Gypsies (Capitol STAO-472) on March 25, 1970. It was issued three months later in Britain on Track (2406 001) with yet another controversial cover: Hendrix as a grotesque puppet with puppet versions of Dylan and Brian Jones on either side.

Hendrix’s soloing on “Machine Gun” alone makes the set worth buying, though there are other fine moments like Hendrix’s solo on “Power of Love.” Despite bearing no resemblance to an “Experience” album, product starved Hendrix fans catapulted the album to top ten status.

Earlier this year, Capitol reissued Band of Gypsies on an extremely well mastered CD (CDP 0777 796414 20) and digitally remastered vinyl (duh!).

Electric Lady Up And Running: The Experience Reforms

Things began looking up for Hendrix: in the spring of 1970 the Experience reformed for a series of live concerts called the “Cry Of Love” tour, with Billy Cox replacing Noel Redding. The new studio, with Eddie Kramer as chief engineer, was almost finished. The reformed Experience’s April 25th performance at the LA Forum (bootleg only) demonstrated that Hendrix still had his chops.

The studio, funded by a $300,000 cash advance from Warner Brothers, opened early June 1970. Hendrix poured through old tapes and began recording new songs. “Freedom,” “Drifting,” “Astro Man,” “Ezy Ryder,” “Dolly Dagger” and other tracks which would show up on The Cry Of Love and Rainbow Bridge began taking shape. Hendrix’s original plan was to release another double LP called First Rays of the New Rising Sun.

On August 26, 1970, Reprise issued Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey Pop Festival (MS 2029) with Hendrix on one side and Otis Redding on the other. In the Jimi Hendrix Sessions author McDermott writes that “...the album’s poor final mix did the collection little justice.” Say what? I think this is a great sounding slab of “live” vinyl, with outstanding high frequency extension: Mitchell’s snare crackles, cymbals shimmer, Hendrix’s voice is vibrant, and Redding’s bass has decent authority. Wally Heider’s recording does a great job of capturing the airiness of a live outdoor concert, and the mix sounds “live”.

The same day this Monterey Pop record was issued, Electric Lady Studios celebrated its official opening with an in-studio party. Hendrix left the celebration and flew off to London. He died a few weeks later, from a bad reaction to some sleeping pills he’d taken in an attempt to get a full day’s sleep before flying back to America.

About six months later, Reprise issued The Cry of Love (MS 2034) with production credits going to Hendrix, Kramer, and Mitch Mitchell. The latter two assembled the album, some tracks from partially finished tapes, in what must have been an emotionally wrenching exercise. Mitchell replaced all of the original drum parts to “Angel,” and on “Drifting,” Kramer needing to match guitar parts fed a direct patch guitar recording back through Hendrix’s Marshall stack, mic recording it in the studio. Kramer recollects in McDermott’s book that it sounded like Hendrix was in the room; so much so that an assistant engineer hearing it from outside the studio came running in, “his face white as a sheet.”

Jimi Hendrix "The Cry Of Love"

Jimi Hendrix "The Cry Of Love"

Compared to the sprawling eclecticism of Electric Ladyland, The Cry Of Love was a tight set musically and Hendrix’s best sonically. With a varied mix including hard drivers like “Freedom” (an anti-drug song aimed at Hendrix’s girlfriend’s dealer), “Ezy Ryder,” and “Straight Ahead” and tender statements like “Drifting,” “Angel” and “Belly Button Window,” The Cry Of Love demonstrated Hendrix’s growing sophistication both as a tunesmith and a lyricist. There was even whimsy in “Astro Man”—Hendrix’s tribute to the comic book character.

Hendrix’s singing had reached a new level of expressiveness, though according to Kramer, he still insisted on singing hidden behind a barricade in the studio. Fortunately, the superb quality of the recording puts nothing between you and Jimi. Virtually all of these tracks were recorded at Electric Lady, and Jimi sounds at home.

The Cry Of Love is the highest fidelity Hendrix album, combining positively luxurious sounding cymbals—creamy and brassy all at once—with deep, well articulated bass and “there in the room” vocals. Hendrix’s guitar is juicy and “tubey” while cutting through with appropriate ferocity where necessary.

In order to flesh out some of the unfinished tracks, Kramer spreads the drums across the soundstage, but that shouldn’t stop any audiofool from luxuriating in this recording’s music or sound. An indispensable record which ends with Jimi’s intimate demo of “Belly Button Window”—written for Mitch Mitchell and his pregnant wife, from the perspective of the unborn child. It’s poignant, funny and a fitting kiss off track from Jimi’s final album.

I didn’t have an American Reprise original which would have been generated from the master tape, but I do have original British (Polydor Deluxe 2302 023) and German (Polydor 2459 397) pressings and a mid-80s Japanese reissue (Polydor MPA 7007). Here the news is good: all three offer outstanding sound on all counts. All are sweet and extended on top, liquid in the mids and detailed and deep on the bottom. The Japanese pressing, with its superior vinyl and overall finish is a standout and the leadout groove offers a clue as to why: while this issue isn’t an original, there are four sets of numbers on the lead out groove area: MP 2494, MPF 1079, MPX 4011 and MPA 7007. Apparently The Cry Of Love has been issued four times in Japan on vinyl, all generated from the original metal parts. Unfortunately this is a budget Japanese reissue so it does not include the original gatefold, nor does the German issue, also quite fine sounding—not the typical bright German sound. The British pressing has it all: great sound and the original gatefold. Look for it in the bins. Speaking of bins, I was unable to locate a CD of The Cry Of Love for this article—apparently it’s available only as an import.

In four short years Jimi Hendrix went from a guitar slinging musical drifter to a pop superstar. His slashing rhythm guitar lines, wah-wah pedal work, and the unearthly sounds he coaxed from the instrument changed in a very fundamental way what playing the guitar meant for musicians in all genres of music.

While Hendrix was not a schooled musician, did not understand musical theory and was not a guitar “player” in the sense of having schooled “technique,” his raw talent and creativity—his quest for new possibilities, coupled with his respect for those who came before him, whether bluesmen like Otis Rush and Albert King, or jazz greats like Charlie Christian and Kenny Burrell, equipped him with the tools to move music forward into uncharted territories—places young musicians today are still exploring, having been guided there by the musical light he shed.

Where might Hendrix be today? He reputedly wanted to go back to school to learn theory so he could better articulate the ideas in his head. Perhaps he’d be leading a hybrid rock/jazz/blues big band. Stories abound about meetings with Miles, Duke Ellington and Gil Evans. Perhaps he’d be writing a modern form of classical music—one of his favorite genres. Maybe his brightly burning star would have faded out. It doesn’t really matter. What Hendrix did create lives on in the hearts and minds of generations of music lovers; his appeal undiminished by time.

After years of litigation, the Hendrix catalog has reverted back to its rightful heirs: his family. Who will get the reissue rights for yet another go round remains to be seen. Hopefully we can look forward to state of the art HDCD transfers, or true 20bit 88kHz or 96kHz sampled transfers on the new DVD format, or dare I dream? High quality all analog vinyl.

Today, there is a twenty song HDCD Hendrix collection, and if you, like me have been lukewarm on HDCD, or even cynical, Jimi Hendrix: The Ultimate Collection (special edition British Polydor 517 235-2) transferred to HDCD by Joe Gastwirt will make you a believer. It did me. If you’ve got an HDCD CD player, you must buy this import disc. In direct “A/B” comparisons between the vinyl and HDCD of “Angel” I could not detect any meaningful differences between the two in the areas which matter most to me: the cymbals sound stupendous on the CD, rich with shimmer and brassy transients. There is a warmth and luxuriousness about the CD's sound, and a three-dimensionality and airiness I associate only with analog. Hendrix’s voice is “there” locked in focus the way good analog gets it. Ambient trails go on and on. “Angel,” also transferred by Gastwirt non HDCD, can be found on Voodoo Soup (MCAD-11236). There is simply no comparison.

After being unable to locate a copy in New York City I borrowed one from Marantz’s David Birch-Jones. Once I heard the disc I was forced to order from Tower International (from the US: 01144 171 287 1510). Cost? About $30. Believe me, if you’ve got an HDCD player, it will be worth it!

Coming up in a future issue of The Tracking Angle: “Hendrix: The Posthumous Albums, Live Recordings, & Bootlegs.”

This article is dedicated to my friend Richard Kuhn, Hendrix fanatic supreme, who took his own life and bequeathed to me his entire Hendrix collection which included dozens of rare bootlegs and imported pressings. His gift helped make this article possible. But Richard, you were a shmuck to kill yourself! And poisoning your dogs? Get a life!

This article also wouldn't have been possible without the superb research done by John McDermott in his book Jimi Hendrix Sessions written with Billy Cox and Eddie Kramer (Little, Brown and Company). Also indispensable: Hendrix: Setting The Record Straight by John McDermott with Eddie Kramer (Warner Books).

Almost to the day this article was begun, and on the day I interviewed Eddie Kramer, I received a copy of Voodoo Child: The Illustrated Legend of Jimi Hendrix (Berkshire Studio Productions, Inc.) created and produced by Martin I. Green. The book, a brilliantly illustrated (by Bill Sienkiewicz) Hendrix “biography/speculative fantasy” includes a fascinating CD of Hendrix alone on guitar in his hotel room or at home, working out “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be),” “Angel,” “Cherokee Jam,” “Hear My Train A Comin,’” “Voodoo Chile”/“Cherokee Mist,” and “Gypsy Eyes.” The sound, recorded by Hendrix on his reel to reel recorder, is intimate and thrilling by the way.

The book itself is sort of a coffee table comic book, with the story told panel and dialogue balloon style. The illustrations, though, bear no relationship to cartoons. They are sumptuous, evocative, and not having art critic chops, way beyond my ability to describe adequately.

Having read the narrative thread in McDermott’s books, soaking in Sienkiewicz’s visualizations proved absolutely fascinating. His richly drawn three-dimensional pastel watercolor style will suck you right in. After you’ve turned a few pages you’ll swear you were watching a movie and not leafing through a book.

Sienkiewicz’s drawing technique and color combinations shift with the narrative, always seeming to be the correct choices to snag the mood and feel of the action. And the hundreds of renderings of Hendrix are all right on target: capturing the essential Hendrix facial expressions and emotions, as well as those of other rock luminaries of the time.

The “script,” written by Jeff Young, is a flashback which starts with the circumstances surrounding Hendrix’s death and then hones in on the key incidents in the star’s life, creating dramatic jump cuts which resonate with the illustrations to create a vivid and moving storyline. As with the Hendrix “tribute” CD In From The Storm, I was prepared to not like Voodoo Child but I ended up fascinated, and I recommend you check it out. The cover illustration will probably be enough to grab you, but if it isn’t, thumb through the book at the store and you’ll probably pick it up. It took five years to create this coffee table special. When you see it, you’ll know why. Before you buy though, be sure to read the end of the Kramer interview.

V/A - In From The Storm—The Music Of Jimi Hendrix

Various Artists "In From the Storm"-The Music of Jimi Hendrix

Various Artists "In From the Storm"-The Music of Jimi Hendrix

RCA 09026-68233-1 limited edition picture disc LP

Produced by: Eddie Kramer

Engineered by: Eddie Kramer

Mastered by: Leon Zervos at Absolute Audio

Music: 10

Sound: 11

When this arrived, despite having Eddie Kramer’s name on it, my thought was: the best way to honor Jimi Hendrix’s music was to play it. His recordings, that is. I was wrong. Kramer’s managed to attract musicians who can play—which is the key to the enterprise.

If you’re going to tolerate anyone else’s version of “The Wind Cries Mary,” the guitarist had better be able to throw some heavy logs on the fire. Kramer obviously thought so too: he teamed John McLaughlin with Sting, adding his drummer and a second rhythm guitarist to fill out the sound. The track is smooth, but it digs in where it counts: in the deep, simple foundation Sting lays out and in McLaughlin’s subtle acoustic fills and his controlled, nimble electric runs which meld touches of Hendrix’s flamboyant style with his own lean, Mahavishnu hyperdrive.

While that track is sans orchestra most of the others feature strings. How does that fit in with Hendrix? Well the point is made in the liner notes that Hendrix dug classical music. So what? He may also have dug pork chops but that doesn’t mean squealing pigs would work in the sonic backdrop.

The point is strings can add a neat accent if the parts are written right and the basic tracks cook. On this album, Kramer and the orchestrators (Joe Mardin, Michael Kamen and Nick Ingman) work sleight of hand magic, slippin’ those strings and things in neatly, using muscular lines which consistently firm up the music’s underpinnings and never drip sap.

After a string-launched “...And the Gods Made Love” fronted by Kramer’s studio manipulations, the set gets off to a hot start with “Have You Ever Been (To Electric Ladyland)” propelled by Tony Williams and Stanley Clarke. See? Kramer didn't fuck around. Buddy Miles handles the vocals, with Doug Pinnick’s (King’s X) backgrounds sounding eerily like Jimi himself. Steve Lukather’s arching guitar backed by horns, strings and some tastefully placed woodwinds help get this sucker way off the ground.

Next up is a way cool “Rainy Day, Dream Away” with Clarke and Williams setting the groove for Robben Ford’s rippin’ wah-wah saturated guitar and Taj Mahal’s oh so smooth vocal. Again the orchestra does great things, trading riffs with Ford’s guitar for instance.

By now you’re luxuriating in the great sound too: the first three tracks were recorded by Kramer at Ocean Way all analog and mixed to analog (see interview). The fourth track is the one with Sting and for the first time since he commenced his solo career, you can listen to Sting’s voice and your ears won’t bleed—even though this track is digital.

I’m not going to continue with a track by track rundown except to say that the instrumental “Little Wing” with Toots Thielemans’ harmonica lead was a stroke of genius, Bootsy’s funkafied “Purple Haze” with strings cooks, and that the set’s highlight for me is “Bold As Love” with Paul Rodgers’ sublime vocal, Steve Vai’s crisp rhythmic, Hendrix-like guitar thrusts, Tony Williams’ timekeeping—particularly the phased lead in to the psychedelic finale, and the orchestral ending topped by Vai’s steaming guitar lead doubled in places by the strings. Wow!

With sumptuous settings, outstanding musicianship (Bootsy Collins, Brian May, Cozy Powell, Noel Redding, Michael Hill, Corey Glover and the others), ingeniously written orchestral arrangements and Eddie Kramer at the boards in a (mostly) all analog recording of Jimi Hendrix songs how can you go wrong? Well you could but Kramer doesn’t stray from his vision. The result is a disc which does Jimi justice while offering a fresh perspective and a sumptuous though still ballsy setting. So sit down and feast your ears! I think you’ll like it. I know Mikey does.

.png)