John Marks’ Bookshelf for Lovers of Recordings #9

A DOZEN BOOKS REVIEWED, ONE A WEEK FOR THE NEXT TWELVE

Here are notes on a selection from my favorite books on the history of recording technology, the history of the record business, and the interactions between recording technology, the record business, and the art of music. One example of what I mean by all that is, in the late 1920s, piezoelectric “crystal” microphones supplanted carbon microphones for radio broadcasting.

Crystal microphones had a better signal-to-noise ratio than carbon microphones. Therefore, the live singers on radio could sing more quietly and intimately. They no longer had to shout to be heard. However, the quartz, mica, or other crystal elements were also more fragile than had been the carbon microphones. So, “shouters” like Al Jolson were out; and “crooners” like Rudy Vallee were in. (Trivia bit: Rudy Vallee graduated from Yale, with a degree in Philosophy.)

This list will be presented as a series of weekly installments. Rather than attempt to rank such diverse books from “Best” to “Somewhat Less Best,” this list is organized both chronologically and categorically. JM

The Bookshelf:

1. The Fabulous Phonograph, 1877-1977

2. The Label: The Story of Columbia Records

3. Do Not Sell at Any Price

4. The B Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song

5. Something in the Air: Radio, Rock, and the Revolution That Shaped a Generation

6. Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947-1977

7. Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording Studios

8. Goodnight, L.A.: The Rise and Fall of Classic Rock -- The Untold Story from inside the Legendary Recording Studios

9. Making Rumours: The Inside Story of the Classic Fleetwood Mac Album

10. Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport ‘56

11. A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album

12. The Vinyl Frontier: The Story of NASA s Interstellar Mixtape

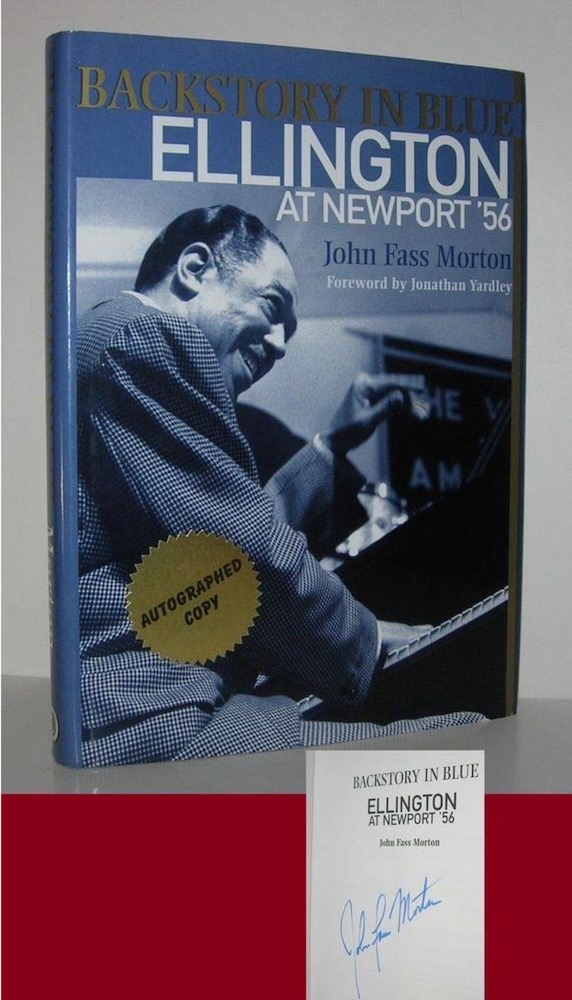

10. Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport ‘56

by John Fass Morton; Foreword by Jonathan Yardley

New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008. Hardcover, 336 pp. ISBN: 0813542820

John Fass Morton’s fascinating book, Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport ‘56, is the story of the long roads to that concert taken by the bandleader, the soloist, the festival promoters, the dancing socialite, the record producer, and many others. Even more important, this book is about why that night remains a watershed in American culture.

In the last years of the 19th century, Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington’s father, a butler in Washington, DC, occasionally worked catering jobs in the Grover Cleveland White House. I think we can fairly assume that it had unusually deep and poignant personal associations when, in 1969, another president, Richard Nixon, conferred upon Duke Ellington the Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

However, such recognition was not foreordained. In thinking about history and historical causation, it is extremely important to be on guard against the temptation to assume that whatever happened was in some way inevitable. Playing the game of “What if?” can be sobering. Had Max Roach not shamed Miles Davis into kicking his heroin habit, Davis easily could have soon met a junkie’s death. One result of that would have been: No Kind of Blue. Yes, modal jazz probably would have been “invented” by others (arguably, it already had been), but it is valid to ask whether modal jazz would have taken the world by storm without Davis’ unique combination of musical talent, charisma, attitude, and personal style.

Backstory in Blue challenges us with the idea that, after World War II, Duke Ellington’s career was in a death spiral. Nearly all the touring big bands had folded, eight in 1946 alone. Individual singers such as Frank Sinatra and Rosemary Clooney had almost entirely supplanted large, finely honed instrumental ensembles as the peoples’ musical choice.

Demographics and simple economics worked against the big bands’ survival. The young people who had cheered the big bands before and during the war were now married, and heading for the suburbs and parenthood. A big band was an expensive beast to house and feed, especially as the ballrooms closed and the remaining work was in small clubs—or such “nontraditional” venues as bowling alleys and ice-skating rinks. Indeed, when Morton picks up the thread of the story, the Ellington band’s only scheduled gig was in Flushing Meadows, at an outdoor, water-themed amphitheater called The Aquacades, a leftover from the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

The unlikely happenstance that saved Ellington’s career—and, not incidentally, brought jazz an entirely new audience—was that a rich married couple hit upon the idea of trying to pull Newport, R.I. out of its own post-WWII death spiral by organizing an outdoor public jazz festival. As they say, the rest is history—but it was never inevitable.

A transplanted Bostonian by way of New York City, Elaine Lorillard was a jazz fan who found that, in Newport in the winter, a Navy Officers’ Club was the only place to hear live music. That gave her the idea to revitalize Newport summers by inviting jazz musicians to play, first at the Casino (which didn’t work out), and then in Freebody Park, a Victorian-era baseball field. Her indulgent husband provided the funding, even to the extent of lending money to keep festival impresario George Wein’s Boston nightclub from closing down.

Time and again, while reading this page-turner of musical, cultural, and social history, I was struck by how terribly unlikely every bit of it was. For all practical purposes, Ellington’s career might have met its end on a dusty baseball field in Newport that night. Time and again, I heard the faint creaking of the hinge of history.

Not long after midnight on Saturday/Sunday night, July 7/8, 1956, it became apparent to those in the know that 57-year-old Duke Ellington’s daring bid to revive his failing career by playing the closing set of the third Newport Jazz Festival had failed. The concert was supposed to have ended at midnight, and some people were already heading for the exits.

Yet moments later, Ellington’s band was suddenly playing on a stellar level. Soon, halfway through what was supposed to be their last number, 1937’s “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” Paul Gonsalves’ onrush of 27 choruses of hot, rhythm-and-blues–accented tenor-sax soloing brought the remaining crowd to its feet.

Amping up the frenzy was Elaine Anderson, a leggy blonde socialite who had jumped out of her seat in a front box and improvised a sinuously expressive solo dance in the aisle and in front of the stage. At least a dozen professional photographers snapped her; Gonsalves’ and the Ellington band’s playing was captured by a remote recording crew from Ellington’s label, Columbia, and by a separate crew from the Voice of America. In due course, a photo of the blonde socialite in full flight would grace the back cover of Ellington at Newport, his best-selling album.

Within days, people the world over knew that something epochal had happened—if only from seeing the wire-service photos of Elaine Anderson’s dance. As Ellington later put it, “I was born at Newport.”

To distill all that into two sentences, if possible:

Before the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, the Big Bands were dying out because their previous business model of providing music for social dancing was no longer relevant. But after the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, Big Bands had a new business model, of playing virtuosic music for a seated audience that had come to hear the music.

Highly recommended.

.png)