Making Good Records Great: Tom “Grover” Biery Reframes Classic Albums for the Contemporary Listener

The Definitive Sound Series Brings Nat King Cole's "The Christmas Song" Into the 21st Century

It’s a remarkable moment to be a record collector. Music lovers have never had more ways to hear their favorite albums in whatever format feels right: hi-res files, streaming on the move, sometimes reel-to-reel and cassette tape—the whole buffet. And yet, there’s a meaningful difference between a solid pressing and a pressing built to be the definitive document of an album. Audiophile labels have chased that ideal for decades: each working to deliver versions that honor the intent and the sound.

Plenty of listeners have caught on. If spending a little more means skipping the long hunt through used bins and getting a pristine, purpose-built edition, the choice starts to feel pretty rational.

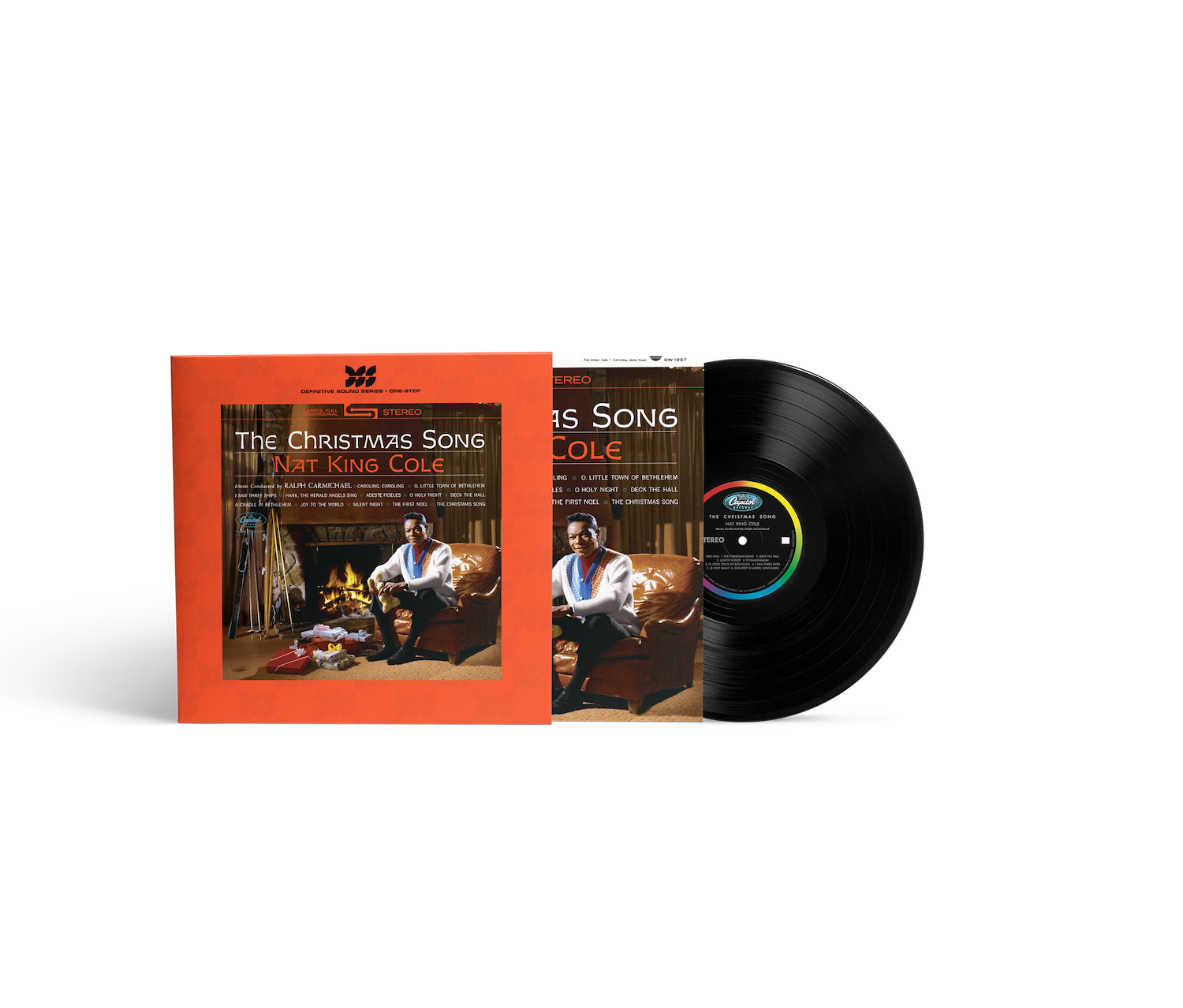

That’s where the Definitive Sound Series steps in. Interscope and Capitol aim to create what they consider the best possible versions of key albums from their catalog. Numbered, limited editions. Gatefold tip-on jackets. A dedicated DSS slipcase. And a “one-step” process that moves straight from lacquer to stamper for maximal clarity.

Their latest release is shepherded by Tom “Grover” Biery, who produced the new edition of Nat King Cole’s The Christmas Song. You’ve lived with these recordings for years, but Grover’s betting this edition will shift what you think you know. It includes two tracks not on the original album - “O Come All Ye Faithful” and “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen” - and was assembled from three separate three-track analog tapes.

Grover’s path through the music industry has been long and impactful. He helped cultivate careers for Metallica, The Flaming Lips, The Black Keys, and others. He led operations as General Manager of Warner Bros. Records and later served as Executive Vice President of BMG’s Recorded Music US division. On top of all that, he co-founded Slow Down Sounds, a vinyl-only reissue label dedicated to thoughtfully curated releases. Their recent project brings newly issued Chet Baker recordings from Bruce Weber’s Let’s Get Lost documentary, mastered by Levi Seitz at Black Belt Mastering from fresh 48/24 transfers and pressed on 180-gram Neotech vinyl by RTI.

So dig into Nat King Cole, revisit Chet Baker, and explore how Grover tests the upper limits of how good a record can truly sound.

ezt: Grover, can you give us a background about your career?

Grover: I've been in the music business my whole life. Started in radio. Ended up, luckily, getting a job at Warner Bros. in 1990. Was at Warner Bros. for 20 years. Started making records around 2004 when I was there. Very much a part of the beginning of Record Store Day. Just over the years, kept getting more and more and more into sound quality. Now, I've got a company, Slow Down Sounds. Underneath Slow Down Sounds, which includes my own label, and that includes partnerships with Warner Records for something called Because Sound Matters.

Then most recently, and what we're here to talk about, is the Definitive Sound Series, which is with Interscope and Capitol. Yes, I do a bunch of things. I wear a lot of hats. All of it centers around vinyl and sound quality.

ezt: You're wearing a hat right now.

Grover: [chuckles] I am. Boo-Boo Records. San Luis Obispo. It all comes back to record stores, by the way.

ezt: The Definitive Sound Series, you guys are touting it here as the pinnacle of vinyl craftsmanship. Obviously, as you know, that is a serious claim here in a market that's really got a lot of premium releases. We just mentioned Chad (Kassem / Acoustic Sounds) and all the work he does, and you're well aware of the market, and the field, and who's doing what. How do you see the Definitive Sound Series individualizing itself in this field? What do you guys feel you're really bringing to the party here?

Grover: One thing that's different, for sure, is I sit inside of Interscope Capitol on these releases. I'm able to tap into resources that no one else can, at least not a third party. If you look at whether it's MoFi, or Chad, or Elusive Disc, and Impex, or anyone that's in the highest-quality space, I've got a little bit of an advantage because Interscope is never going to license Dr. Dre The Chronic to anybody. Because I've done a partnership with them, I'm able to do that with them.

The titles that are coming are things that 9 out of 10 times would be really difficult for anyone to license. On top of that, I think it's really unusual for a major company to actually honor their catalog the way that Interscope Capitol is, where there's a real focus that not only is it about revenue, of course, on some level, it all comes down to revenue. At the same time, it's equally as important, or maybe more important, to honor these amazing records and try to create an experience for the listener that they've never had.

Sticking with Dr. Dre as an example, I don't care how many times you've heard the Dr. Dre record. You have not heard it like the one-step record. That goes for all the titles that we're doing. Whether it's A Perfect Circle on the Capitol side, a very historically important rock record, huge rock record, huge rock band, and the one-step, it's as good as it can possibly sound. We do not cut any corners.

ezt: Chad and I spoke about this a few weeks ago. I think the special sauce here for you and for some of the other labels really comes down to catalog. Catalog is really what's separating a lot of these reissue labels at this point, who can get their hands on certain tapes and certain rights and stuff like that. As you mentioned, Dr. Dre and A Perfect Circle. Now, A Perfect Circle was a really interesting, surprising choice for the opening of the catalog that you're working on here.

Can you talk a little bit about the reasoning behind that and some of the other titles, instead of something maybe a little more obvious? I guess we get used to some of the classic rock being reissued. We get used to the jazz being reissued. It's surprising and exciting at the same time to see some new names out there as well.

Grover: This will be a bit of a long answer if the last answer wasn't quite long enough.

ezt: All right, let's go!

Grover: Essentially, I'm not a purist when it comes to source. Chad is pretty firmly set, and if it's not on tape, he's not doing it (this has recently changed with the release of two Van Morrison albums where the master tapes were unusable_ed.). That's not me. I look at it that there are decades of music that was recorded in Pro Tools, some of the greatest records of all time. You have to get your head around there is no analog tape. I think with a younger audiophile audience that's developing and just super fans. I'm also not just catering. The Definitive Sound Series isn't catering just to audiophiles.

It's audiophiles and super fans because we believe that super fans will enjoy the experience even though you've got to spend substantial investment in the record. We feel strongly that the results will speak for themselves. That's part of it. I also think that I can't recall anyone in that one-step premium vinyl space that's put the effort into records that you wouldn't see as obvious, like A Perfect Circle. I think one of the reasons why is because most of the guys doing it they're not rock fans either.

They don't know A Perfect Circle. They don't know Maynard. They don't know Tool. They don't understand what I'm lucky enough to understand about some of these records that we're doing. Then the key, though, is you've got to really put the effort in to finding what your source is going to be. The other advantage that I have is I get to talk directly to the archivist, the people that know the source better than anybody. These folks, their whole livelihood is based on knowing everything about every record that's in their catalog.

Now, they might not always be exactly perfect, but so far, what I've asked them to do or information I needed, they've been perfect. I have an asset and a tool at my disposal that other people don't have. It's because I've just been doing this for my whole life. I'm friends with the person (Pat Kraus) who runs the Universal archive and the recording studios. I've literally been friends with him for over 20 years. It's all this happenstance that happens that allows for that also.

If you look at something like A Perfect Circle, it's hard to know exactly if it was all Pro Tools, partly Pro Tools. Everything was mixed down on the tape. There's a lot of nuances to this. What we thought were original flat masters. At 192/24, when we listened to them, our ears told us that they weren't. They didn't sound right.

ezt: Does the archivist have much of a say there? I imagine they can. It's interesting to think about digital archiving. Now, we archive things digitally now on our drives in the cloud. We've all named some file, something in our archive that we can't find. What did I name that thing? I guess if you take that experience and compare it with a recording studio session, there's a lot of stuff to really keep track of that's not physical.

Grover: That's correct. Then take it even further, where there's 17 mixes of a song, vocal up, vocal down, all this stuff. Then generally, though, it's all really together on what the final version is. Some people call it the final mix. Some people call it a flat master. Then there's also the final master. In a lot of rock music, or even digital music, there were the loud wars that happened where everything was compressed and loud. You've got to go back a step. You've got to really have the ability to see what is available to start the process of a one-step.

If you don't get a source that you're comfortable is going to show the value in the end record, we just don't do it. It's got to have the right source. Then once you find out what sources are there and you start pulling sources and listening and whatnot, then you've got to go by every version of the record that you can find and start A and B-ing it and trying to like, "Okay, which pressing do people really love? Which ones weren't so great?" There's so much that goes into the overall preparation to even get to what someone's going to cut.

ezt: Grover, it's really easy to find the final source. It's the one that's titled, “Final, Final, Final, Final, Definitely Final Source”.

Grover: [laughs] Not always!

To finish about A Perfect Circle. Basically, we got what we thought was a transfer of the flat masters, but our ears told us maybe not. We even went all the way to test pressing. We did cut a lacquer. We did go through the whole process. We did get a test pressing, and it just didn't work. We started making all these calls, and this is on the Capitol Records store website. If you go to A Perfect Circle, we detail the deep dive.

Essentially, we ended up finding a source to cut the one-step from that had been done a while ago by Ron McMaster when he was at Capitol, legendary cutting guy at Capitol. He's since retired. We literally went all the way, Levi Seitz, who mastered for the one-step. He did the cutting for A Perfect Circle. He actually spoke to Ron to see if Ron could recall the session, what happened, and the place that we found the source that we used, which was a 192/24 file.

It wasn't even in the archive. It was inside of a workstation at Capitol, but the archivist,he's amazing. He was like, "Wait, I think I might know--" back to my point about how I have this extra source of someone like that who knew where to go and look, and, say, "Levi, we made what most people seem to be thinking is a really awesome-sounding version of that record." Yes, it's deep diving, man. It is deep, deep diving on these one-step records.

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

ezt: Yes. Again, it's fascinating to think about it from a digital perspective because I've thought about what you're saying about the digital sources. That so much music has been recorded that hasn't been recorded on tape. What do we do with that? Do we just say, "Well, it wasn't recorded on tape, so we're not going to worry about it?" To be able to track that story digitally must be really confusing and also rewarding when you find the right source, but as you mentioned, you have these guys at your disposal that know the details. They know where the bodies are buried.

Grover: They do. It's a big benefit, honestly. By the way, also, I love analog tape as well. If that's available and it's in good shape and we don't feel any kind of risk in using it, of course, that's what we're going to always use. One of the other differences is because we limit these records to 3,000, and they're numbered, and they're foil-stamped, and they come with a certificate of authenticity. They are truly all analog. We don't take an analog tape and do a transfer and then cut these records.

We cut the necessary stampers, generally five. We cut five different lacquers in order to press 3,000 records, and everyone is all analog. That's something else with the Definitive Sound Series, that when we say something's all analog, then it is. That's another difference, I think, is most folks can't cut the five lacquers from the tape because, A, it's expensive. B, a lot of times, the studios won't even let the actual analog tape out.

Again, it depends on what you're cutting. I'm talking about cutting some of the most iconic records in the Interscope and Capitol archives. If I wasn't inside Capitol, they're never going to license me - like I was saying, they're not going to license me any of these titles that we're doing.

ezt: They don't want to send those things out anymore, for sure. If you want to give a quick summary of the nuts and bolts of what happens with a one-step process, I'd be glad to hear it from your side.

Grover: Yes. The process with a one-step, which we view as the most meticulous way of making vinyl; it's the pinnacle of vinyl craftsmanship. It starts by having to cut multiple lacquers. Those lacquers go ultimately to a convert, straight to a stamper. For every one stamper, it can get you, hopefully, 500 records, maybe 750 records. The whole process is centered around starting with that many lacquers. Then, because you're avoiding going into the process of making a negative, the father, and then making a mother, and essentially, a mother can be used almost forever.

Not forever, but you can make a lot of stampers off of that mother. With the one-step, we avoid the mother, and we avoid the father. In theory, it allows for a grander sound experience.

The noise level on the vinyl that we use, which is called Neotech VR-900-D2, it's like “super vinyl” premium compound. It's more expensive than a regular compound, obviously, but it's dead quiet. The floor, the noise level on a one-step should be very, very low. You almost don't know you have your needle down in between songs.

It's not perfect because it's vinyl, but you try to get it as close as possible. That also allows the music to have a different presentation. Every little nuance comes out. The D2 compound it's very revealing. If you're not stoked on your master, you're not stoked on the recording, you might not want to do a one-step on the D2 because it will reveal what is there. It is not going to leave anything for someone to guess.

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

ezt: For better or worse.

Grover: Or worse.

ezt: We're talking about A Perfect Circle here, but major genre shift here: Nat King Cole's The Christmas Song album, which, thank you, you sent me a test pressing of in this one-step process. It's funny, when it was sent to me, iI was informed, "Look, this is a test pressing, so it may not sound exactly the way the finished product would sound. Keep that in mind."

My test pressing was flawless. [laughter] If that is the first draft, I think you're definitely on the right track for sure. Maybe to segue into how you guys decide what records to work on, but how do you jump from A Perfect Circle to Nat King Cole, and how do you identify what things need to be in the pipeline for this project? Tell me just about how the Nat King Cole work came to you.

Grover: Essentially, myself and the folks I work with on these at Interscope and Capitol, we all are agnostic to the genre. We just all love music.

ezt: Good.

Grover: For me, Nat King Cole works well with Dre, works well with R.E.M. because it's just all music in a way. Especially with streaming, the idea of genres of music went away because people could choose whatever they wanted. Often, it's a hip-hop record or a country record. I think when we come to choosing the title, just things we love, things we think sound amazing, artists, records that feel special.

Even if there's 10 pressings out there, can we beat it? Can we make the absolute definitive-sounding record? That's a bit of how we go through the idea. We literally sit down once a week and go through titles. We've come up with some just an hour ago. If we can get them over the line, people are going to be so stoked because, think of the catalog. Interscope and Capitol, it's pretty good.

ezt: A ton of great stuff. You can share some listening notes or thoughts that you had going through that Nat King Cole process, but I just want to share some thoughts that I wrote down while I was listening with you, and maybe you could just respond.

Grover: Then we can go back because I can walk you through how that all happened.

ezt: That’s great.

Grover: The whole idea of Nat and all that.

ezt: That would be great. I just wrote-- these are like tasting notes, like a wine reviewer’s tasting notes. It was warm, but with woody and detailed warmth. Cole's voice was on full display. Even though some of those songs were songs that I'd heard a thousand, if not 10,000 times in my life, the arrangements and instrument separations felt brand new to me in some ways, those arrangements. The pressing was silent, which was eerily silent, as you pointed out.

I noticed a lot about those choir parts. Sometimes they get smeared and I was waiting for some sibilant moments. I was thinking, "Okay, here it comes," and it didn't happen. Those choirs, it didn't happen, even though it was at the end of a side. You could feel the human characteristics in those choirs. Sometimes when you hear these things, especially on the radio, those background choirs sound like one piece. This felt very different, detailed. I don't mean to be weird, but it was almost like you could hear each individual person. I don't know how many people were in those choirs. The same with the string complexity and those arrangements, too.

There was just a lot of great separation and detail. Those are just some of my initial thoughts.

Grover: Well, first of all, thank you. I'm so pleased that you articulated, as one of the few people who's heard this, by the way, so far, right?

ezt: That's exciting.

Grover: You articulated exactly what we were going for. There was a real thought to what you heard. It's not happenstance or maybe or, hey, let's see. We were very, very focused on, again, the name, Definitive Sound Series. We were focused on taking all the extra steps to give the end user, the end listener, that experience that was as close as possible to sitting in the studio when they made the record. It sounds like you feel we got there.

ezt: Yes, I would say that that's the feeling. It felt very human. It felt very human.

Grover: Let's back up a minute to even Nat King Cole. A couple of years ago, I was involved with the release of Nat King Cole Live at the Blue Note in Chicago, which was done through Iconic Artist Group. Iconic represents the estate of Nat King Cole.

ezt: Right. I interviewed James Saez (at the Tracking Angle).

Grover: Oh, yes. James is great.

ezt: We had a great interview. We had a great talk about that project. I love that record very much.

Grover: I did the manufacturing side and the art side, and getting all the right people, all the right manufacturers together. Because James did such a wonderful job of getting it to that place, we wanted that to be a great end experience for the listener.

ezt: It was a beautiful package. Congratulations. You did a beautiful job on it.

Grover: Nice, right? Yes. Anyways, I've always liked Nat King Cole for years and years and years. No one can have all his records, but I've got a lot of his records. When I got lucky enough to be helping out on that, I just started getting deeper and deeper into Nat King Cole. I feel personally that he's like a big streaming artist and everything. He's obviously iconic and a legend and everything. I feel like, man, he doesn't get his due.

He was the most amazing piano player. He was a great pianist. He was a amazing communicator. He was an amazing singer. He was a civil rights activist early on, like early, early, early days. He was friends with Jackie Robinson. It just goes on and on. When we were sitting around, we just started talking about The Christmas Album. That's how the idea of doing it came about. Then the process of doing it was a whole different trip.

ezt: Yes. Tell me, what did you have? You're going to tell me, but I'm jumping ahead because I'm excited.

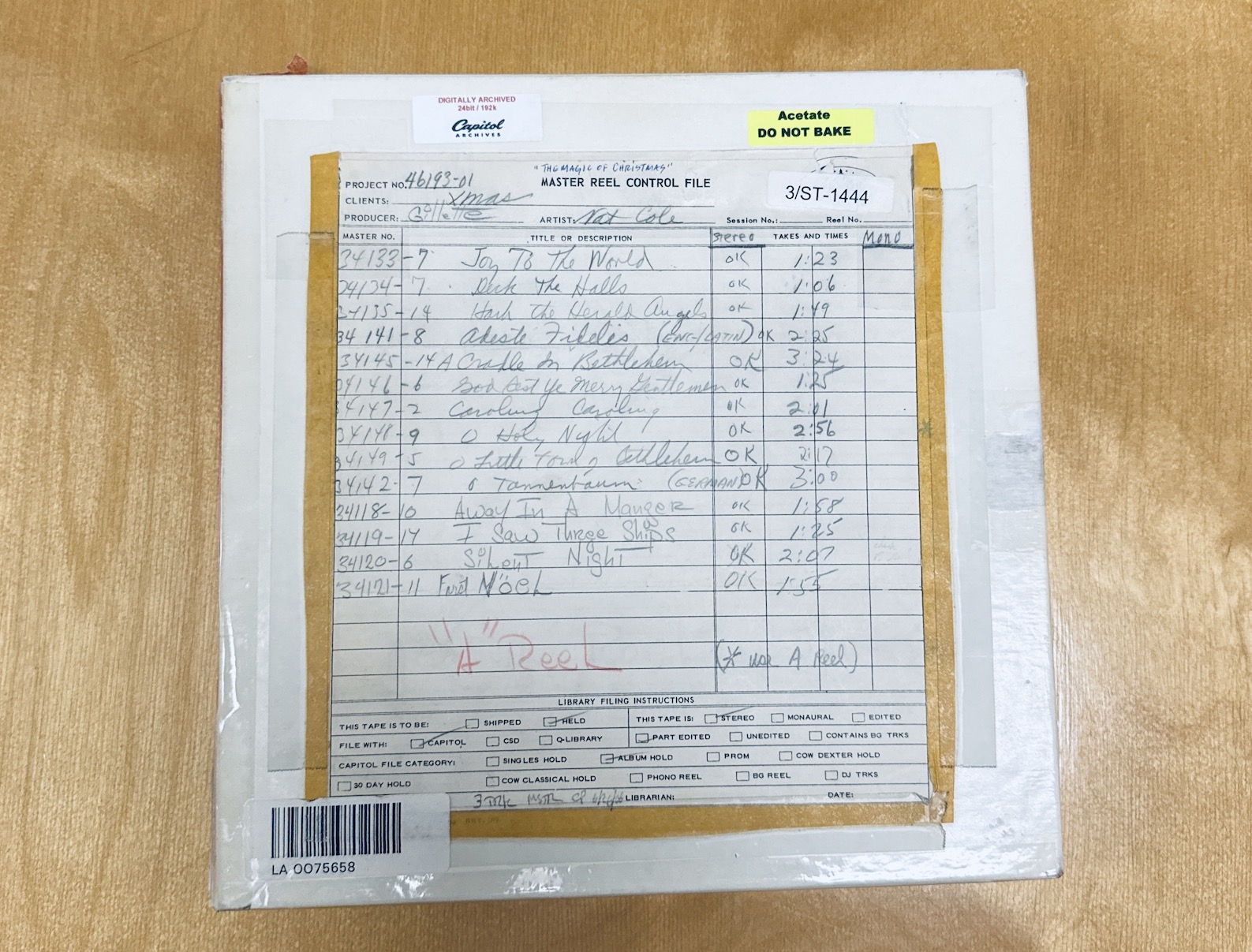

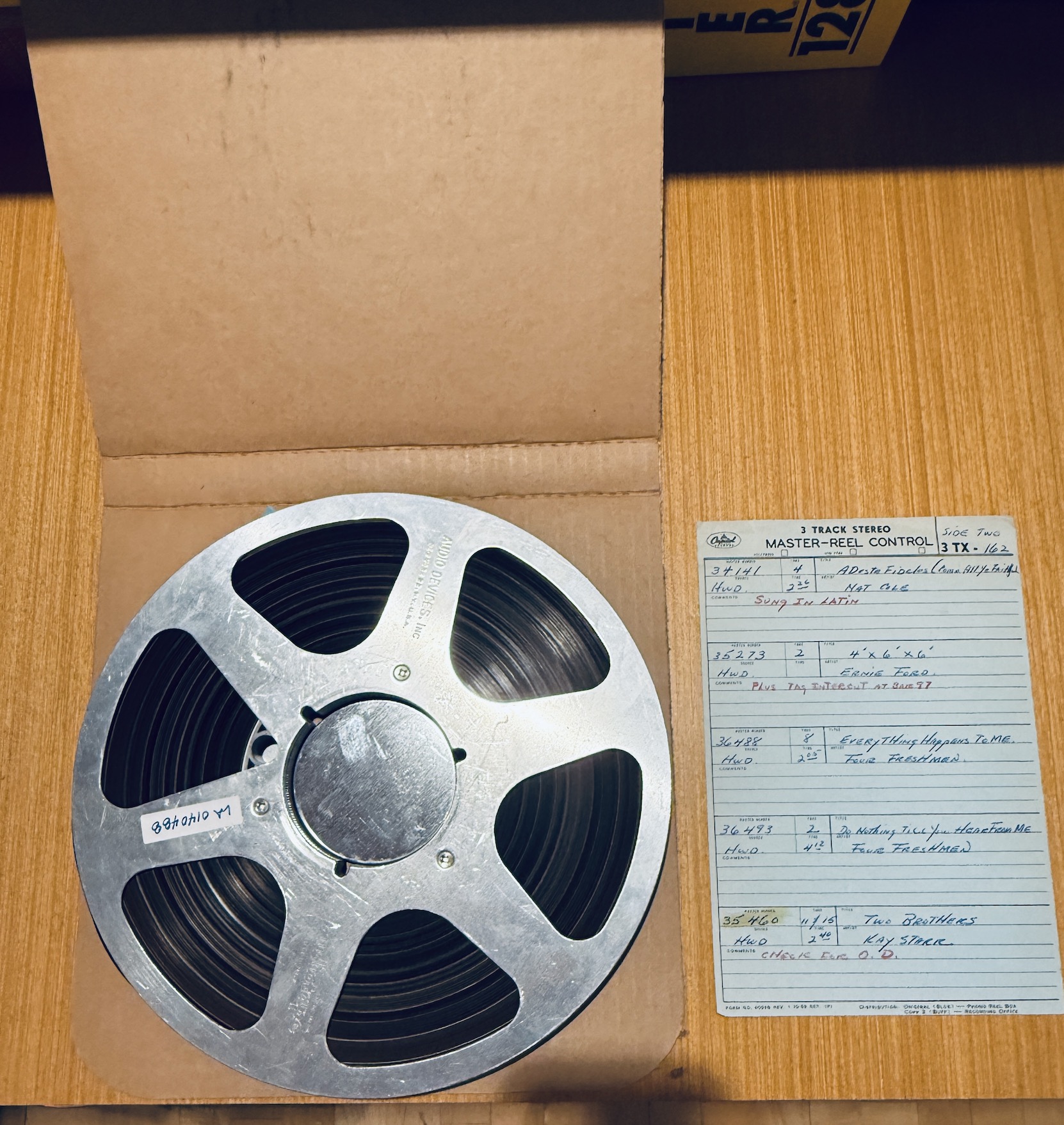

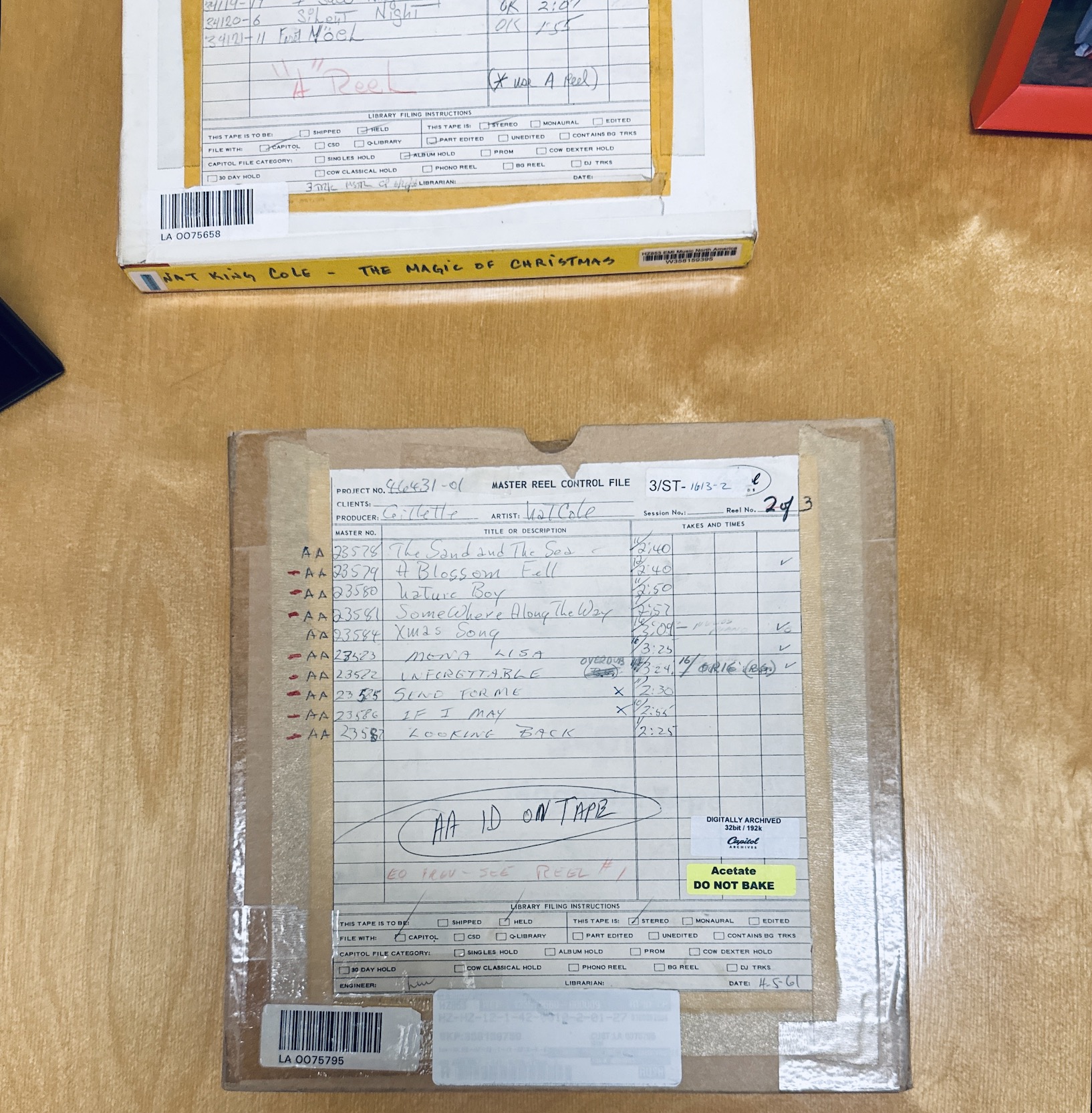

Grover: Well, you have to keep in mind, this is a record that you can find a used, somewhat beat-up copy for $5. You can find an original in really good shape for $25 or whatever. There's tons of reissues. We're not talking about something that hasn't been done a lot. It's been done a gazillion times. It was important to try to get back to that original source. That's what we started investigating. As we got into it, you can imagine with a record that's been done so many times, there were a lot of different sources. The very original source was a three-track analog tape. That was the original master.

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

In 1959, Nat King Cole - he did an earlier Christmas record - The Magic of Christmas, that no one knows about. Then what happened is they rerecorded a bunch of his songs in '61, '62. That's where they rerecorded “The Christmas Song”, which I think he originally recorded in 1947. They rerecorded it for The Nat King Cole Story, and it blew up from there. Then they went back to that original Magic of Christmas record and used the bulk of that, but not all of it. They used the bulk of that to make up the record that we now know that came out in 1962, which is The Christmas Album. That's the backdrop to it, right?

ezt: Interesting.

Grover: Yes. Then, once we realized there was a three-track, we still wanted to get additional sources. We had other versions on vinyl. We also had a 192/24 transfer of what seemed like the original master. Now we find out maybe it wasn't the original master because obviously it's the three-track that we held in our hands. Chris Bellman cut the record at Bernie Grundman.

By the way, Bernie Grundman Studio, one of the few places that would actually have an echo chamber. When you hear that original version of the record, there's a lot of echo happening on his voice, right?

ezt: Right.

Grover: As you can hear, you've heard it. Most people have it, but you can hear that that's not the case with the one-step.

ezt: Very dry. It makes you almost-- well, I don't want to say angry, but it makes you think about how many records ended up bathed in all of that reverb. If you just got rid of that and you get to the core of what's going on, just as you do here, which we all went through with these Beatles reissues also from America, which of course in the Capitol vault's there as well. Strip away some of that echo chamber, that reverb stuff, and wow, you've got a really different presentation.

Grover: Especially with his voice. It's one of the great voices of all pop music. Anyway, so Chris and I sat in the studio for probably, I don't know, over an hour. We listened to the 192/24 transfer because that would have been a lot easier, quicker. It was assembled. We kept A and B-ing it between the other sources that we had and the three-track. The issue with the three-track original tapes, they weren't in the right sequence because they were done for the previous Christmas record.

ezt: I see.

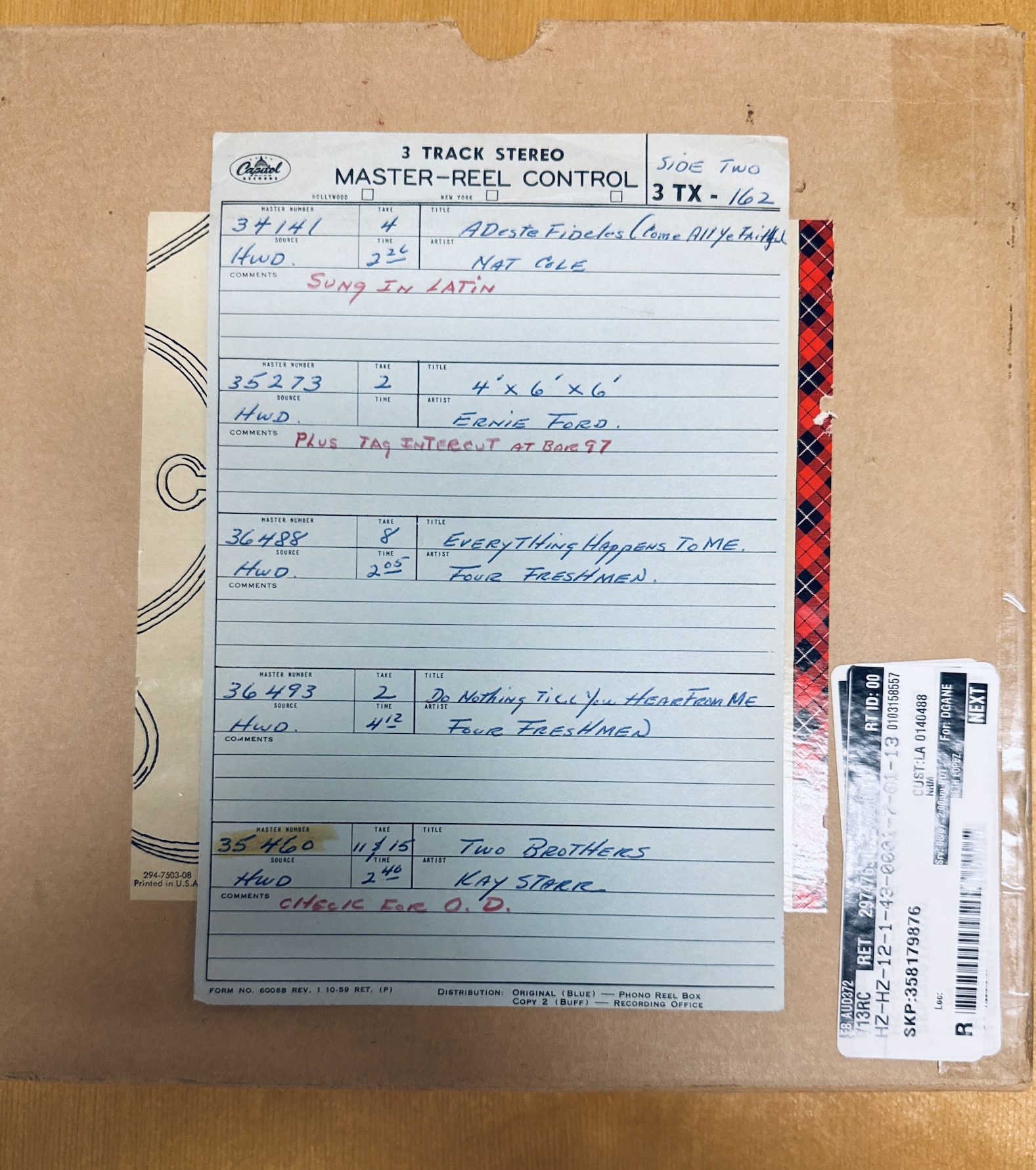

Grover: Most of the songs were there, just not in the order you needed them for The Christmas Song album. Then we have to start weighing out how long is that going to take. Are we even allowed to splice the tapes together to make a cutting version? Then ultimately, I wanted to add two more songs to the album that weren't on the 1962 release. In fact, they've never been on vinyl.

ezt: “O Come, All Ye Faithful” and “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen”.

Grover: Yes. I guess “God Rest” was on The Magic of Christmas. Anyways, both of those stream really well. When I saw 80, 90 million streams on “O Come, All Ye Faithful” on Spotify, I thought, well, we should add it to the vinyl, to the one-step process, because no one's heard that. That's how that came about. It was just looking at some research. That goes back to the relationship with Iconic and doing the other. It's all relationships in the right place, right time, and knowing the right people to even be able to think about those songs that were streaming so great.

Those two songs were on entirely different tapes. Then we had three tapes - fortunately - but they were all three-track. With three-track tapes, this is all new to me. I've known about that process. Chad actually did the Nat King Cole Story from the three-track maybe 15 years ago, 20 years ago at this point. That's phenomenal. Once we got the three tracks and we had the other songs, basically what you were saying in your description and some of the notes you referenced, you've got the music on the left side and the music on the right side.

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Those are two tracks. Each of them both detailed. Then on the third track, in the center is voice. When we're doing the one-step from the three-track, I think it's not like we were remixing anything because that wasn't at all how we even looked at it. We were just trying to get everything as dialed in to what's been presented over the years, but just better. We, of course, could hear his voice with no echo at all. We could hear it completely dry, which, by the way, is pretty phenomenal.

ezt: Yes. Almost spooky.

Grover: I almost died when I heard it for the first time. As a fan and everything, I just can't believe it. Anyhow, we played around, got everything right, got all the music right, got his voice right. Added a little bit of echo to it or whatever treatment. Then we added more. Then we went back down. Then, how about do we want the cut with all the music?

ezt: Sure.

Grover: That's why when I was saying thank you to you earlier, and appreciating your comments, is because everything that you said is what we were saying in the room.

ezt: That's great.

Grover: How do we accomplish exactly that goal of the orchestra not just being the orchestra or the choir?

How do you get it so it's almost its own moment? When I do test pressings, I actually track them into my computer at 96/24 so that I can be in different places. I can listen differently. I'm not just sitting in my big room or my room with my Hi-Fi where I do my critical listening.

I've got four turntables in that room, all different cartridges. Everything's different on all of them. There's something about tracking it back into the computer, back into the digital side, where even something as crazy as listening on AirPods, which I think most audiophiles would be like, "What in the world are you talking about?" There's something about it. If it blows your mind sitting on the beach in AirPods, you’ve hit a home run.

ezt: Well, it's like they used to say, you got to check your final mix on a cassette on the car's dashboard speakers.

Grover: That's right.

ezt: If it sounds good in the car, it's going to sound good on your Hi-Fi.

Grover: By the way, Jack White and Prince both swear by that exact thing. Sounds good in the car, critical listening done in the car. This is a similar version to that. Your point about the choir and the strings and singers, honestly, man, it really is detailed. It really is. It's because of the tape, man. It's why people love analog. It's the warm sound. It's everything people talk about. Is it better than digital? If it's all done right, yes, it is. Digital can be equally amazing if that's done right. This just happened to be a record where his voice, you heard it, his voice drives the whole presentation.

ezt: Again, I'm not trying to be too hyperbolic, but there's a goose bump factor. There was definitely a goose-bump factor to listening to that. Again, it's interesting. You've got this convergence of the audiophile side of things and also the real enjoyment. We're talking about listening to stuff in the car. With this record in particular, and maybe you could weigh in on this, here are some songs that people really associate with the Christmas holiday.

They have a different enjoyment of this music than maybe if they're really serious music heads, and they want to listen to their favorite jazz album in the best possible, no holds barred, who cares what the price is. When I put it on, my 12-year-old son was behind me. He was playing Fortnite and immediately, he turned and went like, "Oh, this is this." It immediately captivated his attention, too. Talk about that convergence between just music for the masses and being presented in this special audiophile presentation as well.

Grover: I never thought of it like that. It's an interesting question because I also like some of the greatest records of all time, nobody ever bought when they came out. Then there's other records that, no matter how big they got, no matter how many millions, tens of millions they sold, they were still amazing. To me, I think it's about the presentation of the record that sold millions and millions and millions, should be as definitive as some unknown record that maybe the tapes were played once ever.

It's going to sound a certain way or whatnot, but to me, I never looked at it as being much of a difference on how to present the records, whether they'd sold 100 copies or 10 million copies. I think the process of trying to get the most out of that needle, out of those grooves, that's the challenge to me. The fact that it's so well known, I think, gives it the “oh, wow” factor when they hear it this way, and that goes for Dr. Dre, A Perfect Circle. Dre is a four-generation record.

People that have heard it so many times are losing their minds over playing the one-step. Nat King Cole, same thing. I think it's a little more obvious, perhaps, because it's that window of Christmas music.

ezt: It's something your grandma loves, too.

Grover: It's in that zone of like--

ezt: You can play it for grandma.

Grover: We kind of all grew up with this record in a weird way, right?

ezt: Right.

Grover: Whether you're a 12-year-old son or your grandma, it's that kind of a holiday record. “The Christmas Song” itself streams unbelievable numbers every year. It's one of the top five Christmas songs ever. You're talking about people being able to access it everywhere, on every streaming service, multiple versions on YouTube, on and on. The one thing I feel pretty confident in is you're not going to be able to hear this version anywhere else. You got to get this version.

It's one of the reasons why it is expensive in some regard. I could argue that it's not expensive at all. I get, for the average person, a $100 version of this album by Nat King Cole is maybe a bit hard to swallow. At the same time, it's 3,000. It's numbered. It comes in a beautiful design slipcase. It's all analog from the three-track. Very unlikely this ever gets done again, ever, like ever, ever.

These one-step records become heirlooms. They become something that, in some ways, it's a luxury item. It's a luxury item that, if you really want it, you can probably find the $100. It's not like it's $1,000. It's not like you're paying a $10,000 premium to get the first car off the line for model 2026 or whatever. It's not that crazy of a luxury item, but there is that side of it.

ezt: Oviously, you're talking about a one-step technology that is specialized, so there's that part of it. I'm sure that the packaging on my test pressing was just the test pressing. Tell us a little bit more. You just talked about a slipcase. What can people expect from the Definitive Sound Series physical presentation? We talked about the other Nat King Cole release that was very beautiful-looking, that you guys did a great job on. I imagine these will be great. What would people be excited to learn about the physical product?

Grover: We only use the absolute best of the best at every turn. Whether it's mastering, whether it's plating, whether it's design, whether it's the pressing, and that goes to the packaging. We only use top-tier people. Every record, other than R.E.M. - which I can explain in a second - it'll be in a gatefold sleeve. Whether it's two records and it's a double gatefold, or it's a single record, we still create the gatefold because it fits into the slipcase nicely, and it doesn't move a lot, and it fits well. You need the gatefold to be able to do that.

ezt: I see.

Grover: It's a tip-on process, so it's a wrap. The difference between just printing on a jacket versus the idea of printing on paper and then wrapping it around, so they're wrap-ons. Then the slipcase is redesigned completely for the Definitive Sound Series releases, where we've got a UV-treated, really great DSS logo that's all crafted over the idea of the record itself. It's definitely building the brand associated with these records by doing everything at the highest level, including the idea that when you pick up the slipcase, it's heavy. It's a different trip. You're holding something substantial.

We try to do everything as authentic to the original record as we can. Sometimes there's reasons why we can't or whatnot, but that's the idea. Because we view these as straight-on reissues, we're not doing a deep dive into putting notes together. There are other people that can do that. You can look online and find everything in the world about the record. We're not doing detailed liner notes to these records. We're just presenting them the way they were first presented.

ezt: Sure.

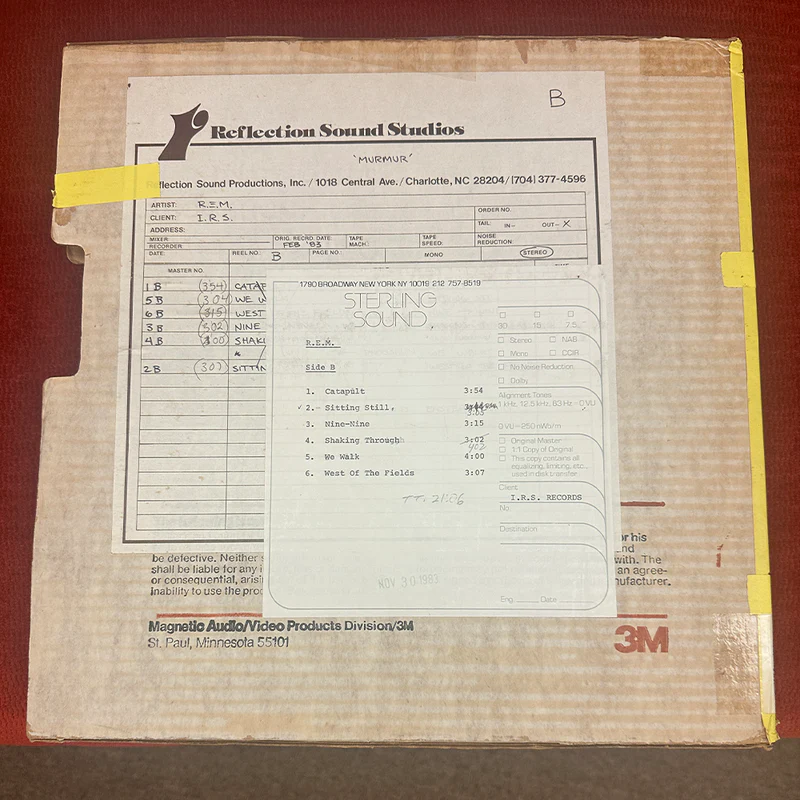

Grover: Exceptions, of course. You could argue that this is not an exact reissue because we actually added two songs. There were two songs recorded at the same time as the album. It was all done in that three-year window. Essentially, it's a reissue. In the case of R.E.M. that we're putting out, I was able to make a case that the first EP, Chronic Town, and the first album, Murmur, really fit together. It was Mitch Easter who did Chronic Town, and then he did half of Murmur. Don Dixon did the other.

There was that moment in the beginning of R.E.M. where those couple years there were all the same. Anyways, they agreed to that. The one-step we're doing for that record, which we don't have the dates or the preorder up yet, but the version we're doing is we're taking the EP and the album in single LP package, still a wrap-around, still a tip on, but we're putting them both into the slipcase. Neither one is going to have a gatefold, but they'll both be inside the slipcase because that way, when people buy it on the front cover, it's going to be Chronic Town and Murmur.

That's never happened either. First time in the history of this most iconic rock band that both records are being presented right here together. I'm not saying that hasn't happened on the digital side, but there's not really a physical - it might've happened like that on one of the Deluxe CDs where they added Chronic Town to the end of it, but there was never the idea of like, here's Chronic Town, here's the beginning, and right after, here comes maybe top five debut records of all time with Murmur.

That presentation is guided by fandom; everyone working on it, massive R.E.M. fans. I'm not sure how many other people would have had the concept of thinking of them going together in one package, but because I'm such a huge giant fan forever, it just seemed automatic to me. That's how I grew up listening to those records. They were together for me.

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

Photo: Tom Grover Biery

ezt: It seems like you really decided to go 33 and a third speed, rather than -- there are a lot of 45 RPMs being reissued. I frankly prefer 33 just because it's easier for me. Was that a decision that you guys talked about, or did you labor on it? Maybe you have those masters, they belong to you guys, so I guess you can do whatever you like with them. You can release them however you like.

Grover: We do labor on it. Truth be told, A Perfect Circle, the first test pressing was at 45 RPM.

ezt: Interesting.

Grover: It wasn't because it was 45 RPM that we didn't love it. It was because of the source. Then once we got the right source, it was like, "Oh, okay." I go back and forth on it as a huge fan. If I buy anything at 45 RPM, the very first thing I do is track it into my computer at 96/24. I've got it to two sides. [chuckles] I guess maybe that's why I'm more of a 33 1/3 guy. I do think 45 definitely allows for a different presentation in the grooves. I also think it affects the listener's experience.

The only reason that I think that we would reconsider maybe doing it at 45 or something would really be if the length of the record's so long that if you did it at 33, it might not be the audio file. It might not be the definitive sound that we go for. We're talking about a record now that's 54 minutes. It's currently a single record. The one-step will not be a single record. It's too long. 25 minutes is too long. 24, maybe. 20, yes. Below that, of course.

I will say that I recently did Prince Purple Rain as a one-step as part of the Because Sound Matters Series. We did it just the way that Prince always wanted it, 33 1/3. Our benchmark for that were the promo 45 RPM versions of “When Doves Cry”, “Let's Go Crazy”, and “Purple Rain”. Back in the day when that record was released in 1984, those all came out as promo 12-inch 45s. “When Doves Cry” on that original 12-inch, 45 RPM is mind-blowing. That was our goal, was to try to get it loud like that.

Would we do something at 45? Sure. We haven't found the right record that seems like it's that yet. Again, keep in mind, this is not just for audiophile guys with $100,000 systems. These are records that are made for somebody who's just getting in the vinyl, who happens to be the biggest Dre fan or Perfect Circle or whoever. We want them to experience it too. I play these records on a $200 Audio-Technica turntable with normal speakers that any kid could have, any consumer could have that.

These records need to sound great no matter where they get played. I feel like when you're focused on super fans in addition to the hi-fi guys, they're used to 33 1/3. They might not even know how to get their turntable to play 45. If you've got to lift up the platter and move the belt over a pulley and stuff, like the Regas, I got a Rega like that. It's a hassle, honestly.

ezt: When you look back on this in a year or so, and of course, you'll have other releases in the pipeline, what will you feel defines success for this series, this line of records? What will you feel is most successful? Selling those things out, getting people for the first time to hear these things. You and the team, what do you think you're really going to look back on and feel like, "Oh, we did that part and we're content?"

Grover: It's a couple different answers if I'm being super honest and transparent. Inside of a big corporation like Universal, or Warner, for that matter, I want these records to sell out. I think it says a lot when you can create something that's a specialty record. It's a luxury item inside this big company. If you can figure out how luxury items, the best of the best sound, can sell inside of a big company, I think that's putting an exclamation point on even my own career. It took me over a year to convince them to let me do this.

ezt: Wow.

Grover: This is something that just showed up. It took me a long time to convince Warner. Fortunately, I knew a lot of people there because I was there for 20 years. My main point person over here at Interscope Capitol is Xavier Ramos. I worked with him at Warner. He was the most supportive guy in 2004 when everybody thought it was crazy to do vinyl. He was all in there with me. We were laughing. I think we started having these conversations in March of 2024, maybe even earlier.

ezt: Wow.

Grover: Again, there's been a lot that's gone into getting it to this point. Yes, selling them out, fantastic. Equally as important to me is also trying to do all that I can to create almost like a new product. I hate calling vinyl or any physical media product. If I can create a new physical media, a new variant, that just becomes more obvious as we go, right?

ezt: True.

Grover: There's never been one-step of a current record, at least not at this level. Somebody might have done a one-step of a current record that just didn't want to take the expense of going through the other process and making a couple hundred records or something. It would be great if we can find a big enough audience for these records where it just becomes a normal variant. No matter what, you got your four color variants, you got this, you got that. Oh, by the way, here's this definitive-sounding version.

That's going to take a lot of cooperation from a lot of people. That'd be cool if that could happen. I feel somewhat satisfied where I see a lot of things. Even you brought this up at the very beginning of our conversation, where we're not doing classic rock records. We would do a jazz record. It's not like we wouldn't, but we also want to do all these other kinds of records that deserve this treatment. Every fan should be able to have the greatest sounding version of a record if you can really make it the greatest sounding version. You can't skip steps.

ezt: That's why you only have one-step.

Grover: Yes. By the way, that's why the premium is there.

Everyone gets paid for their time. I'm accessing people. There's so much that goes into it. People's time is valuable, for sure, including my own. If you saw how anal I am about these test pressings. I think someone made a comment, I can't remember, like no one else does it this way. They don't take it all the way to a test pressing. We do. I've been doing that forever.

ezt: My test pressing was sealed. I was like, "Wait. How do I slide this out?" I'm like, "Oh, the thing is sealed. What's this?" You really don't usually see them that way. [laughs]

Grover: The reason that I flagged it as like, "Hey, just be aware about the test pressing sometimes have clicks here and there, little pops and stuff." The reason I said that, there's a real reason to that. First of all, this D2 compound is very challenging to press. Not just anyone can press these records. It's really complicated. The presses are SMTs. They're legendaries. They're like The Cadillacs.

ezt: Of course, and you're doing this at RTI.

Grover: All at Record Tech, yes. Basically, they've got to fit the press. There's really generally one press running these records. The quality control is hands-on, very hands-on.

It shows you how difficult it is to make these records because the compound is a little different. It tends to show up fingerprints like a little bit. If you barely even touch it shows a fingerprint. If you look at some of the comments online, people are like, "Oh, my record looked like it had this or it looks like it had that, but it sounds amazing." It's like, "Well, do you look at your records or do you play your records?"

It's the compound. It's very finicky. Then, when you have to change the die, and then you don't really get the presses up to full capacity, because with the test pressing, you're making like five copies, 10 copies, whatever, not very many. You don't want to take the expense of running 100 records before you get the ones you're going to release. A lot of times on these D2 records, the

first several dozen that come through the press maybe never even show up in the package because it takes a moment for those presses to really get into groove.

You don't have the luxury of doing that with test pressings. There's sometimes things that show up that will not be in the final record. Again, it's vinyl, so not everything's perfect. Yes, are there occasionally going to be one-step records that someone needs a replacement disc for? Yes. That's just the reality of vinyl. That's why I flagged the test pressing for you. There was a real reason for it, because it's not exactly the same process as making the final records.

ezt: Interesting. Has that D2 formulation been used before, or this is just something proprietary to you guys, or where's that from?

Grover: It's not proprietary at all. Basically, it's what Mobile Fidelity called SuperVinyl. Chad calls it Clarity, but it all comes from a company called Neotech. A guy named Casey Gibson, he's amazing. He's a chemist, and he's put more passion and time and money and R&D into vinyl pellets into the compound than anybody that I know. Between him and Don MacInnis that owns RTI, they started working on this formula several years ago, and then got it to this point of the VR900-D2 maybe four or five years ago, I think. Basically, yes. Other people can use it. It's available. The problem is almost no one can press it. There's only a handful of places that can actually press the records. Yes, it's not cookie cutter.

ezt: You've been really transparent about the process that you're going through with this Series. I certainly really enjoyed listening to it. I think the audience and listeners and buyers of records will appreciate that transparency too. I think it's the right tack. I thank you for sharing all that with me. I really do. It was fun.

Grover: Yes, very much. My pleasure, for sure. I love these records. I love what we're doing. I love that big companies are doing it. I'm most pleased that you totally got what we were trying to accomplish. [laughs]

ezt: I'm pleased too. I'm glad.

Grover: That's awesome. Yes, man. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it, man.

ezt: Thank you, Grover. I appreciate it.

.png)