Catherine Vericolli Resurrects the Funk: Org Music, Westbound Records, and the Pursuit of Perfecting the Imperfect

The Archivist Provides an Inside Look at the Restoration Process Behind Org Music’s Reissues

Teamwork - as they say - makes the dream work. Over the last several years, Org Music has been quietly amassing a catalog of well-produced reissues and original recordings in all genres. On the reissue front, however, the label has reached its goals by employing a select group of audio specialists all working toward the same goal: to find forgotten music deserving of a second chance to reach an audience, and to approach its restoration with straightforward respect and sincerity.

Org Music GM and COO Andrew Rossiter has assemble an A-Team for the most recent batch of reissues that includes mastering engineer, Dave Gardner - who was interviewed here at The Tracking Angle in November of 2023 - and archivist, Catherine Vericolli, who you’ll meet today.

Catherine has had much experience within the recording industry as a studio owner, engineer, and educator. Established in 2006, she created Fivethirteen recording studios in Phoenix, Arizona. She also directed the Archival Department at Nashville’s Infrasonic Sound. Catherine has also taught classes related to analog tape machine operations and maintenance at The Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences. Currently, she owns and operates Central Audio Archiving also based in Nashville where her archiving and digitization work led her to this current collaboration with Org.

The role of audio archivist is a curious one, maybe even a bit mysterious, but - as is the case in many fields - each link of the audio chain is as important as the ones that come before and after it. Roles of the audio archivist may include cataloging and taking inventory of tapes, restoring items that have been damaged over time, digitizing recordings, researching what is available (and discovering what might be missing) and - perhaps, most importantly, overseeing the analog tape transfers. It’s the audio archeology that takes place before final mastering is even discussed.

Detroit’s Westbound Records has partnered with Org Music to relaunch the label with a series of remastered funk and soul classics. The campaign began with Ohio Players’ Pleasure (1973) and continued with albums from The Counts, Assemblage, Dennis Coffey, and Eramus Hall. Most recently in the series is Denise LaSalle’s Trapped By A Thing Called Love (1972) which marks that record’s first reissue in 50 years. The album features LaSalle’s No. 1 hit of the same name and is currently available in multiple formats, including black and “Heartbreaker Red” vinyl, CD, and streaming.

In the interview that follows, Catherine describes the good, the bad, and sometimes ugly world of restoration and how she and Dave forged a strong bond and friendship during their time working - in the field - digging through the Westbound catalog and bringing key parts of it back to life. She also shares some further details and hints about what listeners can expect regarding what might be Westbound’s most revered label members: Funkadelic.

Audiophiles love their audio provenance, but how far down the rabbit hole do you really want to go? That all depends on who you are; but if you’re ready for a deep dive into Org Music's Westbound reissues - or, just the reissue field in general - then read on: Catherine’s got the secrets you’ll want to learn.

Catherine Vericolli spools up a reel-to-reel at 54 Sound in Michigan. Photo by Josh Thomas

Catherine Vericolli spools up a reel-to-reel at 54 Sound in Michigan. Photo by Josh Thomas

Evan Toth: I've been really excited to speak with you since interviewing Dave Gardner which was the first time I'd heard mention of you. I know you did some work with him, and you're continuing to do with Westbound, which is what we're here to talk about today. I'm really fascinated by your career, your life, and I'm really glad to spend time with you today. Thank you.

Catherine Vericolli: First of all, thanks for having me, Evan. It's a weird, niche part of the industry, the archiving specifically. Usually, it's a skill that's incorporated into mastering engineers needing to get to masters to do reissues or whatever. This particular approach with Dave (Gardner), who is one of my favorite humans ever, he's such an amazing guy, amazing mastering engineer, the approach that we did, where we split those two disciplines, where Dave could really just focus on the mastering aspect, and I could really just focus on the archiving aspect and the assets and have common goals in the same room is pretty unorthodox, but also ended up being such a huge advantage for us with this collection.

I've been in the industry for, oh man, almost 20 years now. When I was young, I decided, like I said, I wanted to make records and work with bands, and so I built a studio in Arizona. I grew up in Phoenix, which has-- It's moving along a little bit better now, but has an interesting music scene, to say the least. Lovely people, great community, but at the time, this had been early 2000s, there wasn't really a good studio to track some stuff in with some analog equipment. I decided I was going to build one, which isn't a good idea, but maybe isn't a bad idea either.

I did that for about 15 years. I got burnt out just in the recording process with that particular community, and then the pandemic hit. I was dating my wife at the time. She's also a mastering engineer. I can't get rid of them, mastering engineers. They're everywhere in my life.

ezt: They're all over. They follow you around.

cv: I know. She was living and working in the Bay Area up in Oakland, I was still in Phoenix, and we were trying to land in a city that made sense for us both to be in and maybe work in and Nashville at the time made the most sense. We both moved to Nashville. We worked for a mastering firm there for a few years, which is where I met Dave. Dave worked for the same company we worked for, but he was based out of Los Angeles.

The pandemic, I think, was rough on all of us. We went in our different directions. I really just wanted to work with tape and was trying to figure out a way to make a career out of that without being a mastering engineer, which was not something I wanted to do. I just, by chance, ended up working with some basic archival stuff, just getting into collections. I really hit the ground running because I think one of my first projects was working on some pretty heavy assets here for Third Man.

Dave Gardner searches for gold in the Westbound archives. Photo by Josh Thomas.

Dave Gardner searches for gold in the Westbound archives. Photo by Josh Thomas.

ezt: It's like, if you build it, they will come kind of thing, right?

cv: It's been the story of my life. I always thought I was going to gradually move into things and ended up just being tossed out of the plane right away. Big learning curve really quickly in archiving. There are resources, but a lot of them, there's gatekeeping happening, just like there is in every part of this industry. There's a lot of arguments, a lot of old guys that think it should be done this way or that way.

You really have to find a community, and the archiving community is so lovely. I had a friend, Jessica Thompson, who is mutual friends with my wife and who's an incredible mastering engineer. She does a ton of really, really great work, a lot of stuff for tapes Awesome Tapes From Africa, stuff like that. She was gracious enough to let me fuss around with her tape machine and do a little bit of archiving with her. Then it just spun out of that.

When we left the company that we were working for, Dave had already had this project in the works, but it hadn't really got off the ground yet. They were trying to figure out how to make it happen. All these assets were in Detroit. They didn't want to ship any of them, which is another whole conversation just in this industry. Obviously, they didn't want to ship that stuff. I had worked with Dave on a couple of releases prior to that. We'd done some stuff for Sun through Org Music as well. We did the Dixie Cups, which was wild to transfer that master tape because I know that record so well. We did Linda Martell, which was really great.

I think I ended up doing the stereo for Harper Valley PTA. We did the stereo for that. I'd already been working with Dave. We got along really well. He was like, "Hey, I have this really wild idea. Will you fly to Detroit with me or meet me there and go take a look at all of these tapes at the studio? It's the Westbound collection." At the time, the only thing that I really knew that was connected to Westbound was obviously Funkadelic. I was like, "Well, yes, let's do that."

ezt: Let's check it out.

cv: Yes. That's how it all got started. Then, career-wise, again, for me, it was just like, "Figure it out. Let's do it."

ezt: Someone who buys records, someone who's an audiophile who's purchasing a lot of records, they're looking at the data now more than ever. They want to make sure things are from the original master tape. They want as pure a signal on these new pressings as can be. What can you share to folks about that behind-the-scenes work that goes into actually, "Hey, where are these tapes stored? What's their condition? How do we get them worthy of being repressed?" What have you seen good, the bad, or the ugly maybe in that process?

cv: Man, that is a super loaded question. I want to start with, first off, I see so many records behind you and it makes me super happy. That's my life in a lot of ways, too. I started buying LPs when I was really young. I have too many to want to move house when you get to that point.

ezt: Sure.

cv: I've been a consumer for most of my life. I've seen the trends move this direction and that direction. Then when I got into pro audio, I learned a little bit more. Then when I got into the production end of all of that, into archiving with mastering engineers and reissues, I realized-- It's funny because a reissue is a tricky thing because there are so many different types of consumers, especially nowadays with vinyl coming back, that whole new trend. We've got a bunch of young kids getting into it, which is really great.

You've got the consumer where they're going to buy something because they recognize it, whether maybe they used to listen to it or maybe their parents listened to it, or they recognize it being something that's culturally significant, so they want to check it out. Maybe it's the very first time they've ever heard of this band. You've got that section of consumers. Then you have the audiophiles, of which there are many different kinds.

That's tricky because there's been so much gatekeeping and then very little transparency in the modality of how this happens behind the scenes. I have a couple of theories as to why that is, but what we have is a community of audiophiles who don't have all the information and maybe think that one thing specifically is going to be the very best thing. They have no clue all the steps that go into making an LP. There are so many different little things that can go wrong that are-- The process is so sensitive.

The hardest thing is figuring out where that middle is. You have to nail it. It's tough because you can't make everybody happy. It's impossible. We can't make the all-analog-- I'm going to use the word AAA only once here in this interview because it's not a term we like.

ezt: Come on, I was hoping you were going to say AAA.

cv: It's not a term we like. Direct-to-lathe, analog, tape-to-lathe would be preferable. The AAA thing goes back to CD releases. It's the wrong nomenclature, which is fine. When you have a master tape, it's at least 35 years old, at least. With this collection, we're starting at approaching 60 years old.

ezt: You're talking about Westbound here.

cv: I am, yes, and a lot of collections that we work on. We don't know where those tapes have been: it’s very rare that a collection has been in the same place since its birth. In the example of Westbound, those tapes, they went from Detroit to Memphis, to Canada, to the UK, back to Detroit eventually. We're not going to have all the things that we really want or that we're looking for. We might in some instances.

We don't know how they were stored. Have they been in a damp environment, in a humid environment? We're going to have some mold remediation. We're going to have to incubate the tapes. We have to bake the tapes. There's going to be splice fixes. There's different levels to approaching a collection like this, or really any tape that we're archiving.

A Studer A80 that helped Catherine and Dave on the project. Photo by Catherine Vericolli.

A Studer A80 that helped Catherine and Dave on the project. Photo by Catherine Vericolli.

ezt: I'm hearing you say, not everything was stored the way that the Beatles tapes were stored at Abbey Road. Not everything is in the Iron Mountain in a perfect setting. The majority of things that are coming on the market now are maybe things that were sitting in somebody's closet, somebody's attic for the last forty years.

cv: That's a big part of the lack of education in the hi-fi consumer. Not to say that none of those guys know what's going on, but a lot of them don't understand that absolute pure master tape that you want us to use for an all-analog cut, we can't. Either A: we don't have it. B: if we do have it, the process of cutting a record from tape, there's a lot of transport movement. We're rewinding. We're fast-forwarding. We're having to make sure that our leader is correct. We're having to handle and move that tape on a transport way more times than is acceptable for that precious item.

Also, that tape, especially if it's a big title, it's been played a lot. It's been in a lot of people's hands. People have been like, "Ooh, I could sneak a play and hear what this sounds like right off the tape." We get a lot of that. To use that actual master tape, it's irresponsible. That's the best way for me to describe it. In the cases where we are doing tape-to-lathe cuts, which for Westbound, we are doing some, which is awesome, they're not released yet, but we had to make tape copies.

When we make tape copies, now we have to think about a lot of stuff. We make sure that we're doing it responsibly. We're using the exact same EQ, we're using the same alignment, we're using, if we can, the same playback deck, same type of playback deck, same width of tape, same speed, and all that. If we're making a one-to-one copy of that master tape and then using that one-to-one copy for that cut specifically, is it still pure? That's an argument for the ages. It is our only option.

That's the thing, with the whole AAA crowd, they're like, "We want this thing. We want it all analog." It's like, "Well, we can't. If we did, it's not going to sound like what you think it's going to sound like. It's not going to sound great."

ezt: Of course, I'm asking a question. You know I love my records. I'm an analog lover. I know you're an analog lover, but having said all that and thinking about the process of putting these things together and the difficulty, then why isn't everybody just happy with a really nice digital copy of these things?

cv: You know what? A lot of people are. I think that what it comes down to is that there is this, again, lack of communication and lack of transparency in this part of the business. People are trying to cut and get things out the door very quickly. There's not a lot of time for technical liner notes. Obviously, looking at your collection behind you, you've probably got some great old stuff from the '50s, especially from the Space Age. We'll find a lot of those gatefolds or inserts that are like, "This is stereo. This is what stereo is. This is why we're doing this."

ezt: “A New Dimension in Sound!” You've never heard this before!

cv: Exactly. It's cheesy. We look at it now and we're like, "How cheesy is that?" I have some incredible records from the '50s that have this gatefold thing inside that says, "Here's the gear we used."

ezt: They have all the Neumann stuff listed, which is fun.

cv: You look at that now as an engineer and you're like, "If I just had one of those things." There's an Arthur Lyman record, The Many Moods of Arthur Lyman around that time, that's got a gatefold that has that. I love that. I wish that we could bring that back in a way that's consumable. Consumable, maybe is what we're looking for. Some folks don't care. They're not going to read it. The hi-fi guys, they're probably going to read it, and they're going to go, "Cool."

I think just more interviews like this and things that are made available to educate and to provide information about the process. I know Dave and I both are from the same camp. I'm not worried about somebody taking this information, going and doing it themselves, and taking my gig. It's very unlikely that's going to happen. There's a lot of information you need to know that isn't stuff I'm going to tell you.

Why aren't people happy with a really nice digital copy? Because they don't know that a really nice digital copy might be the best-sounding copy that they're able to get. I don't know. Some people are, some people are not. We come from different generations. I think the biggest problem is the lack of understanding, lack of information.

ezt: Back to your comments about AAA. I know you don't want to talk about AAA too much...

cv: I don't want to use the term AAA, but I'm happy to talk about the process.

ezt: I know. I'm just teasing you a little bit. I guess what you mean is maybe-- I'd never really thought about this until you mentioned it. Do you mean to say AAA doesn't really relate to these records because the whole idea of that SPARS code was really invented to tell consumers about where their digital CD files had come from? Really when you're talking about vinyl, it's almost like it doesn't apply. Is that what I'm catching?

cv: It definitely applies. We've got the three letters, which is your tracking, mixing, mastering, and then final deliverable asset. During the age of CD, you had AAD or DDD or whatever. It's just not the best nomenclature to use when it comes to the process of analog cutting in these days. We're going direct from the analog tape. We're not using any computers or a lot of folks are saying they're not using any computers. Then they're cutting directly to the lacquer on the lathe. It's just a one-to-one situation.

It's not easy to do that. I'm sure Dave will give some amazing interviews about the process, but all that stuff has to be done on the fly. There's not a lot of practice, where as in digital, you can stop, you can set some stuff up, you can set some plugins up, you can have a little bit of automation happening. You really have to make a lot of deliberate decisions. Sure, you can cut as many lacquers as you want, but it certainly isn't free to do that.

It's a different process. It's a different approach. Everybody wants that because they think that it's the purest thing, but the purest thing doesn't necessarily provide the best-sounding finished product because again, these tapes are really, really old. A lot of the recordings weren't great. They weren't great. They didn't sound great. They weren't great sounding. For us to bring something like that back into the modern world, again, we get stuck in that array of consumers, that spectrum.

We can make anything sound as good or as bad as we want. If we were going to do a modern release that's going to compete with the loudness, compete with all the stuff we're dealing with now, that tape-to-lathe situation, we have less options. We're not really able to do as much in that camp. Again, it's a lot of esoteric thinking. We can make anything sound as good as we possibly can. Nowadays, we can take any noises out, we can do anything. Should we? That's the question.

It depends on the release. How many of these versions of this record are we making? Are we making one that's very audiophile-forward, one that's very general consumer-forward? It's not that the process of AAA doesn't apply. It's that the term doesn't really fit into the world of analog in general, if that makes sense.

I'm absolutely for the concept! Just not the term. "Tape to lathe" should be the term used there, but it's really a nerd opinion within some mastering circles. Personally, it's not a huge deal for me. "AAA" is a term that more people understand and assume means there is no digital processing, so I take it as face value when reading it in an article, etc. I think most people do.

The workspace at 54 Sound Studios. Photo by Josh Thomas.

The workspace at 54 Sound Studios. Photo by Josh Thomas.

ezt: When I was a kid and we were buying CDs, the CDs that were DDD were fancy, "Whoa, this thing is digital. The whole thing is digital. This is a luxurious Michael Bolton CD," or whatever it is that we had. That was certainly a selling point back then. Now, not so much.

cv: It's funny because, in the world of making records, we spent a lot of time in the '80s trying to take noise out of everything like, "Oh, let's get rid of tape hiss. We have to have noise reduction. We got to get rid of this hiss." Now we're spending all this money to develop plugins to put it back in. It's just a trend. As far as this particular collection is concerned, going back to the question where it was like, "How do we prep? How do we approach?" it depends on the size. Again, when we got to Detroit, we didn't really know what we were in for. When we got there, we realized we are in an insane room. This is insanity. There's so many assets here. The personnel were all pretty kooky. Very, very, small group. We had a very small amount of time to prepare and do a significant amount of work for a release schedule. The first thing that Dave and I had to figure out was how we weren't going to lose our minds. Also, we had to not get too excited because especially if you're in a room with unreleased things and you're a fan of the band, you have to compartmentalize that.

ezt: You have to stay focused on the task at hand.

cv: Yes. Distract you from like, "Okay, we need to get to work." First things first is we need to figure out, okay, what do they want to release and where the hell is it? Is there some filing system that someone's implemented prior to us getting here or are we just kids in a candy store flipping through? Hopefully wearing a mask in this situation because we did have a lot of mold.

ezt: Oh, no.

cv: That's the first thing we need to do, is find all this stuff, and find as many versions of the things as we can. We might have masters, we might have safety copies, we might have dupes for CD, dupes for re-release, dupes for cutting with cutting EQ, noise reduction, printed tapes for making cassettes. We either had a whole bunch of choices of masters, or we're missing something.

ezt: Of course, the dupes that you probably found who knows who made those? Who knows how well that was done? What machines? Was everything calibrated when that was made? You might not want to necessarily trust all those dupes either, I imagine.

cv: You don't. Again, when you're getting into this, you have to fall back on fundamentals. When you're looking at a tape and it does have documentation, which is a gift because nowadays we don't have all that stuff that we need, hopefully, it'll have the speed, it'll have the equalization, so the print level. It'll have a track sheet, or somebody wrote something on it. It'll give us a little bit of information like a date, maybe the studio it was done in, or a name.

Then as we look at the entire collection overall, we start to see trends. For instance, a lot of the tapes in, I believe it was 1972, don't quote me specifically on that, a lot of the tapes were copied quickly in Memphis. Some were copied quickly in Canada.

Then they went to the UK. We were like, "Okay." Some of this stuff came back. For what we had masters for, actual masters, obviously, that's what we'd like to use because that's going to be the purest form. We don't have any cut EQ, we don't have any deviation from the original print, as far as we know (meaning EQ that is printed specifically for cutting direct to LP back in the 70's. The actual master tapes are what we prefer to use because there's no cutting EQ printed on the masters, therefore there's no deviation from the original printed mix. Even a safety copy is better than one with cutting EQ, or any EQing at all). In a lot of the cases, we don't have those. We've got copies, we've got dupes... What we're doing is we're bringing all that stuff together and looking for the best possible version that is as close to the original as we can find.

We're going to transfer all of them. Then, through that process, we're going to start, again, to see trends like, "Oh, this one that's got noise reduction tones on it that doesn't even have noise reduction because they were bulk copied with a bulk standard, where they printed just these tones on top of everything," whether or not it needed it, then we can start to come to these conclusions. It's a lot of investigative work. It's like audio archaeology in a way where you're just like, "Okay, the more time we spend with this, the more we're going to figure out what's going on.

Then, of course, we have the history of the release of the record. We've got the one that came out in '69, the one that came out in '72, then there was another one that came out in-- We might have a master for each of those, or half of a master. Maybe we have the A side for this one and the B side for that one. The first thing was to find and then [laughs] organize it as best that we could and try and keep our brains in order. Then get a baking schedule because those tapes are going in, being dehydrated for 14 hours, and then cooling for 14 hours.

ezt: That's interesting. It leads me to my next question. Before I ask it, Andrew and Dave had invited me to go to Detroit to see a little bit of what you guys were doing. Hearing you describe it now, I'm glad I couldn't make it. Definitely I would have been in the way. [laughs] I would have been like, "Oh, what's that? Catherine, did you see this thing over here?"

cv: We had our fair share of that. The first time we went out was a reconnaissance. We had a little bit smaller of a release schedule that we were looking at. We were still trying to figure out, again, what it was we had. I know the Ohio Players release was Pleasure. Initially, I think they wanted to release Pain, but we weren't happy with the assets that we had. We weren't happy with what we were going to be able to release and work with. We deviated to a record that we thought would be a better option. Again, those are things that happen in these campaigns. It's you have an idea and then you get there.

Our first one was a shorter schedule. It was in the summer, so it was a little bit more bearable. We had 30 tapes to transfer, or 20 tapes to transfer, something like that, in 4 days, 5-- It's not a lot of sleeping that's going on there.

Catherine and Dave Gardner During Tape Transfer. Photo by Josh Thomas

Catherine and Dave Gardner During Tape Transfer. Photo by Josh Thomas

ezt: Then back to the other question I was going to ask. Here you are joining me in your studio. For those of you that are watching the video, they're seeing your impressive background there, your studio. For those of you listening, Catherine is sitting in her impressive-looking studio.

You and Dave fly out to Detroit. You're there, you're digging around moldy tapes, you're trying to make some decisions on the fly, what about equipment? What are you using to make these transfers? You're bringing stuff with you? You certainly can't rely on what you're showing up to find. You don't know what you would find? How do you equip yourself appropriately to get through a job like this without-- I'm just a little confused as to how you would ship things and how that would work. What does that look like?

cv: Again, like I said, the first time we went out, it was really just reconnaissance, "Let's see what we've got." We had some meetings before we went about what gear was available. They had a tape machine we were happy with for the source deck. They had some noise reduction we were happy with. We were using Dolby A, which is old, '70s noise reduction, which some of these tapes, we did multiple prints, some with noise reduction, some without. They had a great pair of big monitors and the studio was lovely. They were pretty prepped for the most part.

ezt: The studio with the number, what's it called?

cv: I believe it's 54 Sound. Joel, the owner over there is an incredible guy. The first time we got there, we didn't want to piss anybody off. You have to really respect what's going on. You need to respect the assets. Everyone's really sensitive around it. It's a little bit of tiptoeing, not because we felt like there was a reason to tiptoe, but when someone's allowing you to come into their legacy, basically, and thumb around in there, there's such a huge amount of trust. Dave and I really wanted to make sure that the communication was really open like, "Hey, we don't have this. We do have this."

Back to the gear stuff, they had Pro Tools. They had a great tape machine, which was an (Ampex) ATR102. For that, we were basically just going straight off the source deck. At the time, the first time we went, we were just doing all digital prints. It was all archiving straight to digital and then doing a digital release and then doing a digital cut to vinyl for that stuff.

They had the noise reduction we needed. We brought our own converters for that one. I think we used Burl converters on the first go around. We had a lot of success on that first go around and it changed how everybody wanted to approach the rest of the archive in a way. It was like, "Okay, cool. Let's release some more stuff. Let's do some even more cool stuff. Let's do all analog releases. We're going to go back out to Detroit." Now we had to bring some gear because we needed two tape machines, obviously.

The signal flow was relatively annoying for that. Essentially, we had a source deck that was printing our digital capture, which was Y-cabled out. Simultaneously we're doing a tape copy. We have two decks running. Then that second deck is also simultaneously printing to another digital rig so that we can have a checkpoint between all three so we can make sure that everything is right where it's supposed to be.

Then we also had a turntable set up with as many original copies of these records as we could find. At the end of the day, that's what the consumer is used to listening to. Do we have the right version? Is this correct? When we had moments where we were like, "Does this sound right to you? Is this weird?" which Dave and I had a lot of them, which is great because we're always questioning what we're doing, trying to keep track of it all, we could go back to those LPs and check to make sure that what we were looking for was what we were using.

A Part of the restoration hub Catherine and Dave Assembled. Photo by Catherine Vericolli

A Part of the restoration hub Catherine and Dave Assembled. Photo by Catherine Vericolli

ezt: It could be a totally different take. It could be a totally different mix. It could be who knew that they recorded the album twice and you're spending the time on the wrong one?

cv: The first time we flew. I brought a case with some MRL (Magnetic Reference Laboratory) alignment tapes and a bunch of head stacks and the TSA absolutely loved that. That was fun going through that. Then on the second go-around, Dave met me in Nashville and we drove up. We drove, I think it was the ice apocalypse week in Detroit. I think it was -6!

ezt: That's why I didn't come. There was a huge storm!

cv: Dave did not pack enough socks. He was like wearing his Vans. I was like, "Dude, what are we doing here? We need to get you some--" We immediately went to a very Michigan, I think it was Menards. I don't know if Menards is the correct shop. We found this place that just had gloves, hoodies, hats, and stuff. We looked like crazy homeless people who hadn't showered, eaten, or slept in days. We were in the studio and it was freezing in the studio.

The energy was actually incredible at the end of the day. There were also cameras and they were filming it. There were a lot of moving parts. I'm ready to cue and there's six things we have to cue, but camera two isn't ready. I'm just like, "You guys..."

ezt: Do you have plans to go back there or did you feel like you did what you needed to do? I would imagine it's a honey hole, right? If you kept digging...

cv: Again, the reissue process is lengthy. It's a big whirlwind being there, getting all that stuff prepped, and then it has to be mastered. Then it's got to be cut, then it has to pressed to test presses, and then there's a release. It's a lot of hurry up and wait. We did enough releases as far as I know for a schedule for this and only Andrew over at Org can attest to this, but for at least I think a couple of years.

We ran quite a few things. Whether or not we have any reason to go back, I don't think so. I would love to. There's a lot of stuff in that studio. Again, those decisions are not up to us. If they decide they want to do something else, then, of course, we'd be happy to go back. It's definitely a wild process. It was too for Dave and I on a personal level because we've never really done that thing in that way. It was a lot of making decisions right when we got there, replanning, going like, "Okay, wait. No, that's not going to work. We need to do it this way."

What I love about Dave is he's just as OCD as me but in a totally different way. We're both obsessed with really getting something that's as good sounding as we can, getting a transfer, and getting a print or a tape copy that is really going to set Dave up for the most success when it comes to doing the mastering process. Then I've been out to LA to work with him and just sit with him on a couple of the cuts. It feels like this team effort around this. I'm super lucky that Dave called me to do this because it's something that we want to do more of.

ezt: You just see those waveforms, you're like, "Look at that waveform. This is going to be sweet. We nailed it."

cv: [laughs] I wish it was that. It's so weird because talking about Denise LaSalle specifically, I had not had an LP copy of that yet. Andrew, I know with the fires in Los Angeles, everyone's just been so inundated, but he dropped some stuff in the mail to me and it just showed up yesterday. I was like, "Oh, perfect timing. I'll put it on and get started." There were a few things. There's a Dennis Coffey that I hadn't heard yet, some test presses for some upcoming stuff, and the Denise LaSalle.

What's wild is that when you're in that situation working, especially if you're doing archiving work, you really focus on the tactile and the physical asset. You're really focused on making sure nothing's physically wrong that's happening. Then you have to focus on if the print is correct, if the EQ is still good, if you're losing high end. There's all these very specific things that you're listening for. You're listening more for problems.

Even though the material that you're listening to is really fantastic, and it's the master tape of this fantastic thing, you don't really get the full experience until you put the record on six months later, a year later at your house and you're like, "Wow, this record is amazing. It's really amazing." I will say with the Denise LaSalle stuff, when we put that master tape up, there were two of them. There was an A side and a B side. It was two 15 IPS reels. I think those were dupes.

I don't know that those were the original masters. Again, we're working with what we've got. I just remember putting the A side up for that. This was a record that I knew about, but hadn't really had time to discover it or hadn't really listened or heard it before. I remember putting that tape up and hitting play and just being like-- Dave looked at me and we were just like, wow, this sounds insane, this sounds amazing. This master tape sounds-- he was like, this is great, it's going to be such a joy to master this. Just let it be what it's going to be.

ezt: It's interesting you say that. I have the record here in hand and had a little bit of the same feeling when I put it on the turntable. Obviously, I wasn't playing the fresh tape in the way that you guys were, but I was really surprised. It's got a huge sound. The bass is just really buoyant but not overwhelming. I don't want to say it sounds modern, but it sounds as though it was maybe one of these records that's engineered to sound like something from the late '60s or early '70s, because the balance on it is just so nice. It really is a really nice-sounding album. I imagine the tape, that's what it was when you guys grabbed it.

This video isn't the transfer that Catherine and Dave created, but provides an overall sonic impression

cv: This particular record was cut in Memphis at a studio called Royal. I think it might be on the back of the record there.

ezt: I didn't even realize. I was assuming it was recorded in Detroit.

cv: This one was cut in Memphis at Royal Studios by Willie Mitchell.

ezt: Who also arranged it, by the way.

cv: Yes he did.

ezt: Arranged by Willie Mitchell and Jean Miller.

cv: Just a couple things about a little bit of the history around that studio. We'll move on from that topic, but Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, his son is an incredible engineer and he is responsible for this incredible legacy that is that studio and everything that's been recorded there. They're still making just amazing records at Royal. It's not a studio that's easy to get into to tour or check out. It has not changed a lot since those times. It has a very Motown vibe or Sun vibe where that room is still pretty old. They didn't move a lot of stuff, which is, for a reason.

It's an incredible studio to be in. You can feel the energy that's in there. Willie was also an amazing engineer. Amazing. That's the beginning of why that sounds so incredible, why the low end is so good, why every song on that record is a group, every single one. Denise LaSalle wrote the majority of it. Just pretty incredible.

ezt: The songwriting part really makes the story a lot more interesting to me too. She wrote some great songs here for sure, and continued to do it.

cv: Oh yes. It's not surprising because of the provenance of where that record comes from, that it sounds as good as it does. Another “hats off” too to Dave, because Dave has this ability to use a lot of really amazing modern tools to enhance what that record is supposed to sound like. Sometimes you'll get a reissue, a record where you're like, “ah, it just doesn't-- it sounds too new. It doesn't have that grit, doesn't have that soft round balance to it,” especially with a record like this, that's '70s soul and R&B. Dave just really, really nailed this one. He nails most of the things that he works on. He's excellent. When I played it back, I was like, yes, this sounds like the best version of what it's supposed to sound like, but it still sounds very much from 1972 and it still makes all that Royal stuff shine. It's a really good release.

ezt: That piggybacks a little bit on, I think what you were saying earlier, as far as it's not just about the tape. Everybody, can get hung up on, hey, this is the tape, but it's also the machines that you're using--the whole chain, which some labels really go crazy trying to recreate the chain. What is it people want? What does the consumer want? Do you want that thing exactly the way the thing was, or do you want it to be somewhere in-between? Who's buying it? Who are we making this for? I guess all those questions come up.

cv: That's the hardest part, is who are we making this for? That's a question that's impossible to answer. There's no answer to that. The only thing that we can do is based on the information that we have, is to try and respect that piece of art as much as possible. If something on it sounds really funky and weird and wrong, which is technically wrong, which is a lot of stuff on the Funkadelic tapes. That stuff is not perfect. It wasn't supposed to be. If it was supposed to be, then it is perfect the way it is. Maybe one side is louder than the other side by quite a bit. That's part of that record's legacy. Do we fix that?

ezt: What do you do? I would have a different answer than you would.

cv: Everyone will. Again, it's a matter of really taking as much time to think as much about that and have some really mindful folks working on it. We were really, really lucky with this campaign to have that. I don't know what that means exactly, but when these releases have come out and I've actually been able to sit down and enjoy them from a consumer listening perspective and not try not to break my brain while working, my listening experiences, it has been very much that.

Like, “oh, this is the way this feels right. Feels good.” That to me is a success. It's not going to be a successful listening experience for every single consumer that buys that. I'm sure I would not want to reissue Beatles records. That would be a nightmare, or something where there's so many opinions and it's so important to so many people. You just do the best you can and you try to get as close as you can. Another great example is, I don't know if you got a copy of The Counts record, It's What's Up Front That Counts?

ezt: I don't think so. No, I didn't get to do that.

cv: That, we only had one master of that. It didn't have any low-end tones on it. There was just no low end. There was no reference for me to align my tape machine, to play back the low-end frequencies of the record.

ezt: Do you think there was a reason for that or why that was?

cv: I don't know that they printed them. They printed a 1K and a 10K tone. I remember there was noise reduction and sometimes they did, sometimes they didn't. It was a matter of, now we have, together in the room, Dave and I, we are going to make some savage decisions in a way. What is this record going to sound like now? Because the low end is incredibly important to any release, especially an R&B release, especially that. I was like, this is how I'm feeling. I feel like this is about the level I would do it out for this. Dave was like, let's give it a whirl.

I have to, backwards, recreate a level for that. which is nerdy and technical. We don't need to get into that right now. We dialed that in and we hit play on the tape, and it was like, I don't know if this is supposed to be the low end, but this is going to be the low end. It just had a quality to it. I don't know if it's correct because there's no way for us to know if it's correct. The listening experience, based on that decision that we made in that moment, it was all we could talk about for the next two days. We kept it on there and that was that release.

I love the way it sounds. The digital release also sounds really, really great. Streaming sounds great. Again, you're making a lot of decisions that if you're super mindful, you should feel like it's wrong. You should feel like, I shouldn't be the one to do this and I'm just going to put everything I've got into it. I'm going to ask as many people in the room how they feel, what they think. I'm going to ask hopefully a guy that is a historian around that, which we have, we had one on the team. I'm going to ask the guy that was maybe in the room when it was tracked. I'm going to play it back. If everyone's excited, then that's it. Hopefully we get some folks that really like it and we've gotten really close. Again, we're filling in a lot of gaps.

ezt: Listen, that's a lot of what life is about. People are making decisions all the time, whether it's medical decisions or legal decisions. Sometimes it's a matter of life and death. In your case, it's just, we want this thing to sound good. You can also get wrapped up in questioning and analyzing and then nobody gets to enjoy the thing.

cv: Oh man, without question, Dave and I had a lot of talking each other off of the edge of the abyss on a lot of things. Which is great because that means that we're in it, we're both in it and we're in it for the same reasons,

ezt: I think this is a movie. I think there's some kind of movie here.

cv: Yes. There are so many stories. I don't know if I can share all of them, or I would. The whole experience for Dave and I in Detroit working on the Westbound catalog was magical. It was Lynchian, and rest in peace to David Lynch, who we've all missed forever. There were just some things that happened where we were like, what? Are we in a dream? Is this a dream? Are we dreaming? Then another thing too, not all of these assets were easy breezy. Some of them were in rough shape. There was lot of mold remediation, taking things apart, not having a lot of workspace.

There was a little promo video that came out that they did for the RSD comp, the first one. There's a moment where I'm doing some mold remediation and I have a flange on the top of my head, because all the tables were broken, so we didn't have-- It was really, really wild. Wild experience. Then a lot of splice repair. When you have a tape like that and you get it and it plays back, and it sounds good, and it's 60 years old, it's a feeling where you're like it's like you cheated the universe. This thing is not supposed to be alive anymore, and here it is.

ezt: One step away from the dumpster and you rescued it.

cv: Yes. It's going to be good. It's going to be great. Somebody is going to hear this for the first time and it's going to inspire them in some way. Those are the moments that are really, really great. We had quite a few of them. Did you see the Assemblage release?

ezt: I have, yes.

cv: That tape wasn't in the studio. We were super bummed and we were like, man, where is it? We really want to release this. This is supposed to be really cool. It's a weird band to be on Westbound. It's little rocky, a little psychedelic-y. It's funky at times, but it's definitely more like psych rocky than you would think it'd be for a band. That record is really tough to find. It's super expensive. We were like, man, we'd really love to re-release this. In the final hour, we found it. It was in a different building somewhere else, but it showed up at the studio and I didn't have time to bake it. I didn't have time to incubate it.

I was like, it looks like this is a copy or maybe the tape looks newer. The only option that I have with the time that I have left, which was the last day-- I think David already flew home. I was like, I'm going to put it up on a hit play. Hopefully I won't have any shedding and maybe I'll get really lucky. I put it up on a hit play and there was no shedding, and it was great. I was like, that's magic. That's magic. That should not be the case. There was an energy around this endeavor that-- Dave's got a lot of funny stories too. We were just really cold most of the time we were there.

There's a lot of things to consider. I think the biggest thing is just really trying to be mindful as much as you can around the physical asset, around the studio owner, be really communicative. If you have an opportunity to try to educate the consumer in a way that doesn't upset anyone or-- I think that Dave and I, we like to take those opportunities if we can, because I feel like it's better for the industry. Especially with records being $50.00 now, $50.00 for deluxe edition, whatever, Coke bottle green or something. If you're going to spend that much money on something, it'd be cool to open it up and have a little bit more information about how it was created.

ezt: You talked a little bit about getting these records in and you get the finished product from the label. When you have a moment to enjoy it and kick up your feet, you enjoy it. I'm just curious, how do you think about yourself as a young person, thinking about a career, thinking about what you're going to do, when you have that moment of holding this thing in your hand that you were instrumental in creating? Do you ever think about yourself as a younger person and where you ended up in your career, this really interesting little niche?

cv: Sometimes. I'm the type of person that's always questioning whether or not it's good. Is this good, or am I just thinking it's good? Is it supposed to sound this way? That's just my OCD brain. Maybe it's good that I'm in this niche part of the business because of that. Maybe not. Sometimes yes. Sometimes I think about how I got here. Mostly I just have this huge hope that people are going to be into it, the right people are going to buy it and it's going to get into the right hands, and it's going to be really enjoyed. I hope that it's enjoyed by a really broad spectrum of folks.

I would love a huge audiophile or a huge fan of one of these records specifically to buy that and just be like, man, it changed my whole year. I'd love for a kid to buy it and be like, never heard this band before in my life. It's like, now I'm going to go and buy a bunch of old R&B or get it, discover some part of music they didn't even know existed. I think a lot about a listener's experience that isn't my own. I did put on some test presses yesterday for an upcoming release. It sounded so good that I think I just laughed. I think I just started laughing through most of it.

I did have a moment where I was like, wow, I'm so, so, so proud. I'm so lucky to have worked on this. For it to come out and sound as good as it does. It depends. Most of the time I just feel like, man, I'm so happy that I'm not haggling over $300 at the end of some session. You know what I mean? Not that I don't still love bands. Funny enough, I just actually produced a little LP for a band out here. That's really great. I don't know. That's a tough question to answer.

ezt: That's why I asked it!

cv: I wish I made a lot more money doing it. It's hard because when you get into this, really the only way to catch onto more cool stuff is exposure. You have this huge amount of energy going into a project and when you're doing it, and it's like all of your soul and your brain and your heart, and then it's like, you're just like, when is it going to come out? Eight months! Then eight months from then, you're like, oh yes, that was wild.

ezt: That happened. Yes, that happened.

cv: Again, a lot of insanity and then waiting. We're excited. I can't say enough good stuff about Andrew over at Org. I've never ever worked with a label or a label entity like Org, with a guy like Andrew, who is just so supportive and really wants the consumers to just have a really great experience. They don't really leave a lot of stones unturned when they do stuff. They've got so many different types of music and different things that they offer, and they get into a lot of cool stuff. He's just such a sweet guy. I remember he sent me an email shortly before Ohio Players came out, which I think was the first release. He's like, how do you want to be credited on these? I was like, dude, that's amazing.

ezt: Original master tape transfers and restoration.

cv: Unless you're a master engineer or you're a producer, you don't really get credited. You just don't get credited. They'll get credited on something, whatever. Normally, we don't. For him to ask, I was like, this is really great. Thank you for asking. It doesn't happen all the time.

ezt: When you think about, again, back to our other comments about people understanding the entire process, everybody's excited about mastering engineers, which is fine because they have such an important role, but it's also folks like yourself that are the real key in getting the stuff and cleaning it up, and making sure all the technical things are there that-- we could argue what's more important. You guys can arm wrestle over it sometime. Every part of that chain is really as important as the other parts.

cv: It is, and it's a lot of stuff. It's a lot of stuff. Consumers get really excited about things coming out, like, oh, are you going to put this out, are you going to put that out? Or what's coming, what's coming, what's coming? Then they'll rush the store and they'll pick it up and they'll buy it, and they'll listen to it. That experience, hopefully it's a good one, but that's it. So much goes into reissuing a record. Obviously, so much goes into making a record, tracking a record, mixing, et cetera. Again, reissuing stuff, especially if you're getting into master tapes, and even if you're doing it from '90s sources like DATs and ADATs, that can be even more difficult.

ezt: It's a whole other ball of wax.

cv: There's a lot of stuff that goes on to make sure that it gets made and then everyone has to get along. Labels have to get along with whoever owns that catalog. Maybe they do, maybe they don't. 6 different people, sometimes 20 different people have to approve it. They're the simplest of decisions. It's amazing it gets made at all. Oh, and then it has to get cut and pressed at a pressing plant. My wife owns a record pressing plant here in Nashville. I always thought it was the craziest idea to open up a record pressing plant, and I still believe that it is. When I saw records being made on a record press, I was like, this is horrifying. I don't know if you've ever seen it.

ezt: I have.

cv: Violent, horrifying process. This is the opposite, in every single way imaginable, that I handle my records, or store my records, or feel about my records. Precious things that, don't scratch it, don't put it down wrong, store it right, make sure it's in a dust cover, don't--

ezt: put on your white gloves.

cv: Don't even drop that. I have to do that because the needles got--

ezt: Then the press comes in, “whammo!”

cv: Then you watch it being made, and you're just like, are you kidding me? This is how they make these things? So many things can go wrong. So, so many things can go wrong between the time it's archived or digitized - and sometimes we're digitizing off of an LP because that's all we have - to when it's packaged and released. It's just insane. I feel like the more the consumers can know about that, I don't know, that'd be cool. Maybe they'll be like, I hate records, I don't ever want to buy one. Just ruin the entire process for them, which maybe the mystery is part of the magic.

There are some really incredible things upcoming with Funkadelic specifically, but we're doing all analog cuts. They're 45s, 45 RPM.

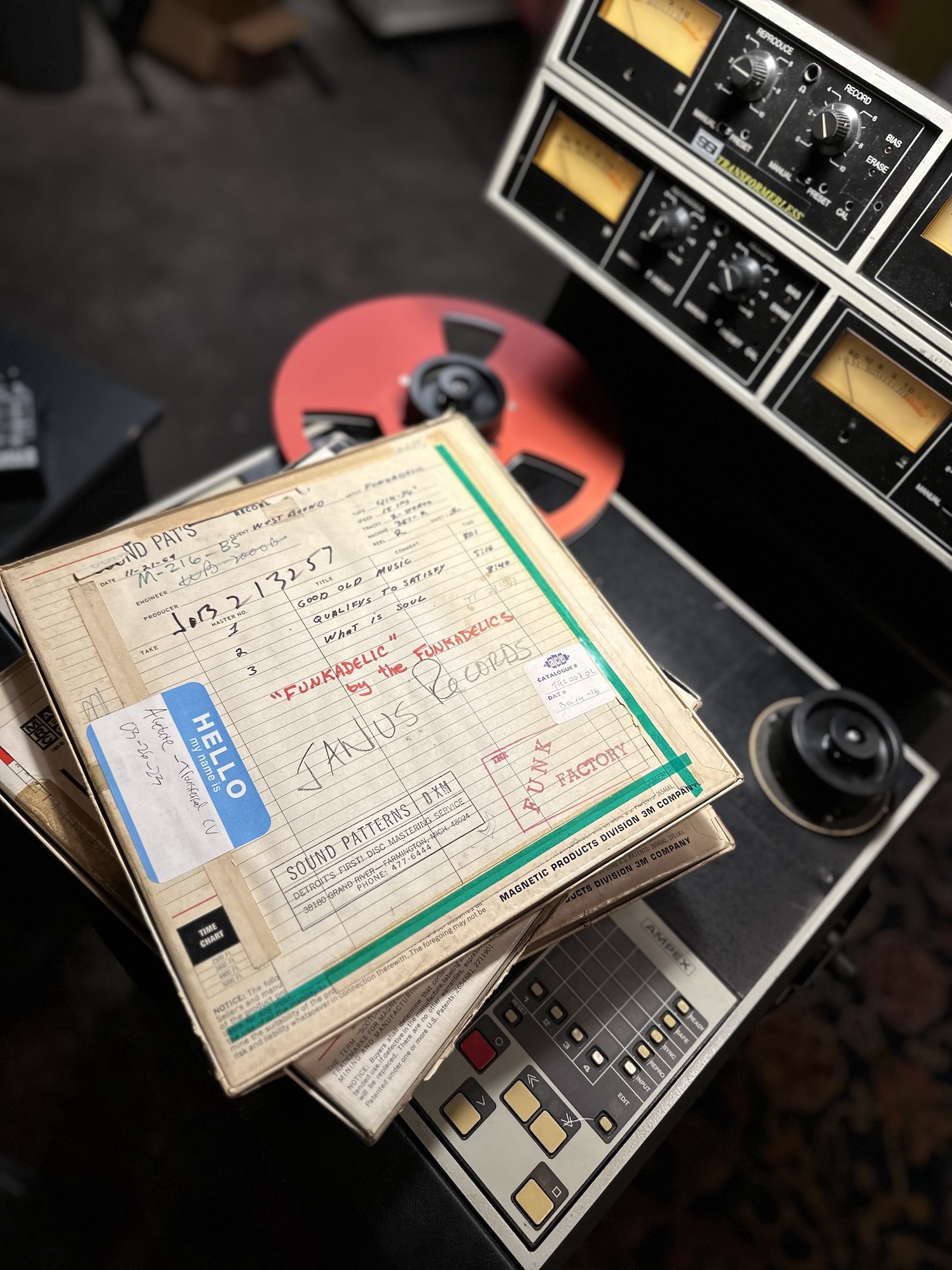

"Funkadelic" by Funkadelic. Photo by Catherine Vericolli.

"Funkadelic" by Funkadelic. Photo by Catherine Vericolli.

ezt: Oh, really?

cv: We are doing a double 45, all analog, direct-to-lathe, tape-to-lathe cut of, at least, Funkadelic - Funkadelic, the first one. I just got the test presses. We were the most concerned about this because it's the first one we've done and we have more upcoming for Funkadelic.

ezt: Funkadelic, right. You must have grabbed them all, I'm sure.

cv: There's too many. What I can say is we're going to do the ones that we should do. They'll also be a regular single-disc LP release as well. The 45 test presses sound insane. They just sound so incredible. They don't sound new...

ezt: They sound right.

cv: They sound what they're supposed to sound like. I'm super, super excited about that and I hope that everybody else is too. I know the Steve Hoffman guys have really gotten wild on the forums about whether or not we're going to release Funkadelic. Obviously we're going to release some Funkadelic.

There was a lot of buildup around, are we going to be able to pull this off? We did tape copies. There's a potential, I don't know, but there might be some liner notes, some technical liner notes that will go in, which will have some of this information on it. Like, here's how we did this.

ezt: Maggot Brain on a two-disc, 45 RPM release?

cv: That I cannot confirm. The only one that I can confirm is Funkadelic. I don't have a release date though.

ezt: These have never been released on 45 RPM.

cv: I don't think they have. It is such a disservice to them to have not been. Dave did such an incredible job cutting, and hopefully the next one that we do, I'll be out to help him cut it. At some point they'll release a press release about when that's coming and what's happening. If you like Funkadelic and you're into that, and you like the campaign so far, highly recommend picking up a copy of that.

ezt: Catherine, I really appreciate your time.

cv: Yeah, thanks so much, I appreciate it. I hope folks will be into it!

.png)