Piano-Palooza

Virtuosic performances on the keyboard from Maurizio Pollini and Friedrich Gulda

The music of Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) has, for most of my musical career, more or less eluded me. It may be because of his lack of non-piano output, or perhaps because his two piano concertos, while containing inspiring piano writing, didn’t really pass on that inspiration to the orchestral parts. I remember many rehearsals of boredom counting rests while listening to the brilliant melodic lines that Chopin gifted to the piano, but not us!

My woodwind playing resentments aside, I’ve been sorely remiss in my lack of Chopin appreciation, because his music written in his chosen form: the solo piano piece, is truly enchanting. And there is no better encapsulation of what this composer could do with short form ideas than in his 24 Preludes Op. 28.

Polish composer Frédéric Chopin

Polish composer Frédéric Chopin

The early to middle romantic period, when Chopin was composing, was a time of musical intimacy. Composers like Robert Schumann, and Franz Schubert were pioneering their music not for the mass crowds of concert halls, or in the royal courts, but in the salons, where small groups of the cosmopolitan wealthy, but non-titled, bourgeois would gather to talk about art, culture, politics, and perhaps most importantly; to listen to music and poetry. It was this stage in which Chopin wrote and performed, primarily in the Salons of 1830s Paris, the same Salons that helped propel the revolutions of 1848 and establish the second French republic.

Chopin once said that “the crowd intimidates me, its breath suffocates me, I feel paralyzed by its curious look, and the unknown faced make me dumb.” This may be why the composer shied away from larger ensemble compositions that would facilitate larger venues and larger audience. The composer clearly preferred intimacy, and intimacy is definitely what comes across when listening to his work, especially the 24 Preludes completed in 1839.

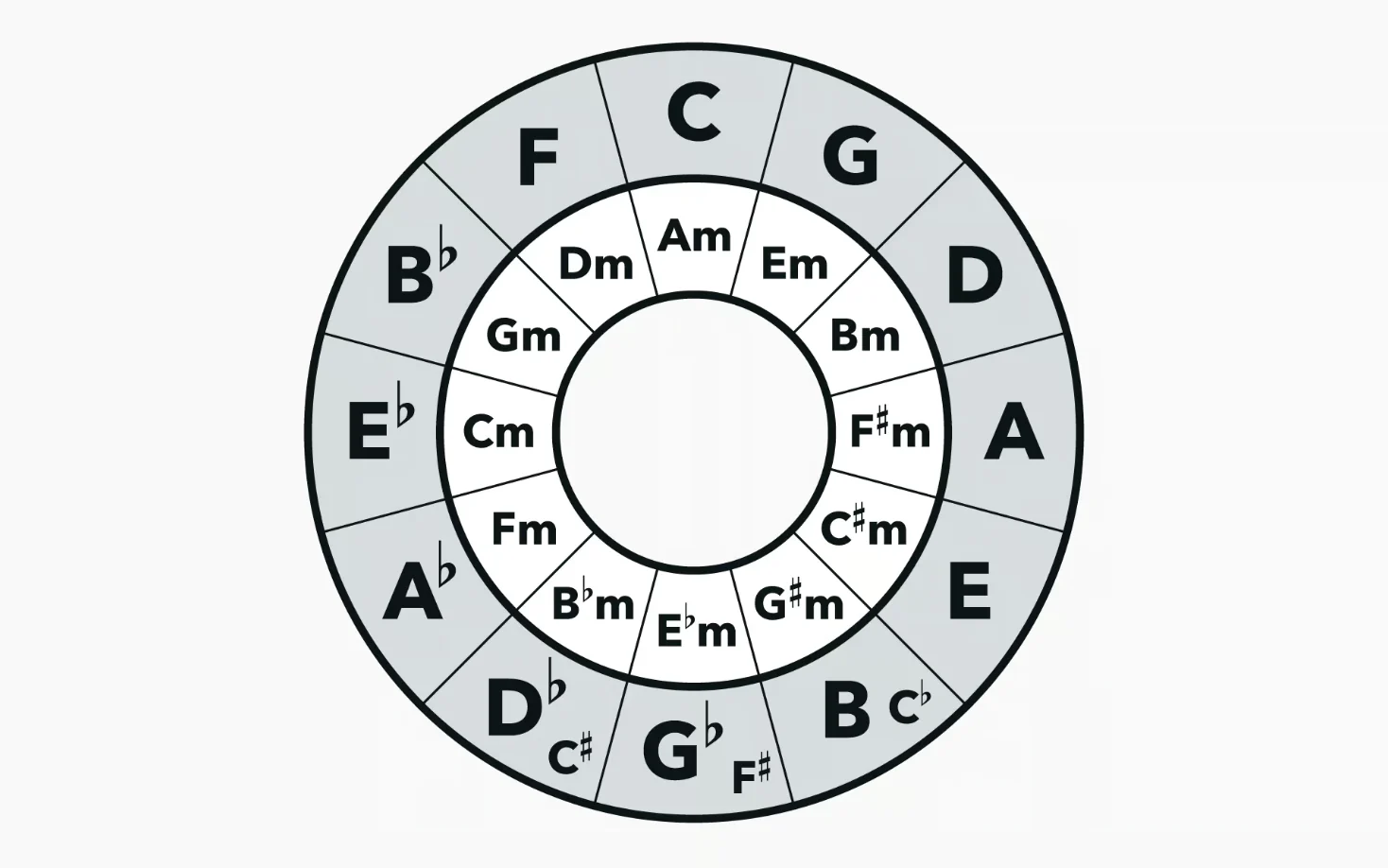

The idea of a cycle of preludes, traditionally an introduction, was nothing new when Chopin approached the format. J.S. Bach’s famous 48 preludes and fugues are a notable example. But while Bach’s cycle follows a cycle of keys rising by a semitone, Chopin’s Preludes follow the circle of fifths, so the first prelude being in C major, it is followed by its minor relative: A minor, and so on throughout the circle.

The harmonic Circle of Fifths which Chopin used to organize his 24 preludes

The harmonic Circle of Fifths which Chopin used to organize his 24 preludes

The works are short, and are meant to capture a particular mood, feeling, or individual idea. Most of the preludes here are less than 2 minutes in length, and each of them are meant to stand alone as individual works. They range from the haunting and subtle, to the explosive and powerful. A full kaleidoscope of emotional range and color, from utter contentment to despair and desperation, can be felt when listening to these works played by competent hands.

Fortunately, Italian virtuoso Maurizio Pollini’s hands are more than competent, and give one of the standout performances of this repertoire on record. Pollini works with great dedication to bring out all the written indications in Chopin’s score, and highlight the harmonic structure of the work. Because of this his Chopin is dramatic when called for, but also reserved when not. He doesn’t overly sentimentalize lines that don’t call for it, which is especially apparent in the famous E minor Largo that will undoubtably be the one melody anyone can recognize from this set. Pollini does not drag the tempo down and overindulge in the sorrowful Largo, but rather plays a more reserved hand, and because of that the overall affect of the prelude comes across more clearly than some more indulgent readings I’ve heard over the years.

This set has long been one of the “essential” Chopin recordings out there, and that’s saying something given the fact that there’s stiff competition from the likes of Argerich, Moravec, and Arrau. But fortunately, the remastering work done by Emil Berliner here should seal the deal, because the refined performance by Pollini shines through on this vinyl version, which contains some of the better recorded piano sound I’ve heard from the label present or past.

What makes the piano sound “right” here? Well for starters, the transient attacks of the keystrokes have a brightness that reminds me of hearing the instrument live, something I’ve always noted lacks on many recorded instances. Also, the octaves of the instrument are balanced, there is weight and depth to the lowest notes, something often critically lacking. In recordings I’ve heard where there is bass depth to the lower octaves, the strikes often sound muted in their attack, not here. I do wish there was more midrange bloom and warmth, but the nicely balanced lows and highs are a decent trade. On Rubenstein’s ‘Living Stereo’ solo Chopin recordings, there is spectacular midrange bloom on the piano sound, but the other ends of the range just do not sound as even and full as this example here. And when Pollini really gets going into more turbulent passages, the weight and clarity of this recording becomes a huge strength.

If that description sounds like your cup of tea, this record will satisfy your itch, and the combination of essential repertoire, standout performance, and excellent sound mean that this is an LP from this series that you should not miss. One of my favorites in the Original Source Cycle so far!

Music 10/11

Sound 9/11

After last year’s successful reissue of Piano Concertos 25 and 27, DG has blessed us with another Gulda concerto disc, this time featuring the heavy hitters, the Concerto No. 20 in D minor K. 466, and No. 21 in C Major K. 467. These two concertos are among Wolfgang Amedeus Mozart’s (1756-1791) best known and most performed works, particularly No. 20.

Mozart’s Concerto No. 20 in D minor is a special piece, as it’s one of the rare minor key piano concertos from the classical period. It’s also one of the composer’s works that survived in popularity long into the 19th century, with romantic composers and performers such as Beethoven championing the work. The opening passages of the first movement in the orchestra are tumultuous and dark, not providing a melodic theme until further along, when the piano enters with a subtle whisper trying to hush the storm of the orchestra.

The second movement B-flat major ‘Romanze’ is more reserved, with the typical grace and poise in the melodic lines begun by the solo voice. Even this movement however, has some unusual elements such as frantic virtuosic runs later on when minor themes rear their ugly head. The Finale is frantic and features a long development back in D minor which does not transition to any new key, but resolves in the final coda to D Major, a surprise resolution to a rather emotion laden concerto that can either be interpreted as hope or satire. With Mozart, sometimes you never know.

The premier in February of 1785 was a huge success for Mozart from both critics and the Viennese public. This may in part be why the composer penned a follow-up concerto in just four weeks, and thus on March 9 of 1785 the Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major was premiered with the composer once again at the keyboard. The original, autograph manuscript of Concerto No. 21 in C Major

The original, autograph manuscript of Concerto No. 21 in C Major

I would not call the C Major concerto nearly as dramatic as its predecessor, it possess more classical sensibilities which are heard right away in the opening with its traditional introduction. However one thing the C Major concerto keeps is the incredible virtuosity in the solo line, and this work excels on the balance between energy and poise.

The second movement ‘Andante’ contains longer melodic lines than Mozart had previously employed, with gorgeous string and wind melodies floating over compound meter ostinati. and wanders into remote key changes in an almost dreamlike manner. This movement has most of the meat of the concerto in it, and it was so beautiful that director Bo Widerberg chose it to feature prominently in his romantic 1967 hit film Elvira Madigan. Once you’ve settled into your dreamlike wonder, you are shaken awake by the brief but incredibly catchy third movement ‘Allegro Vivace’, that you will find yourself humming long after the stylus slides into the run out groove.

Gulda and Abbado’s handling of these two works is superb, and both are readings that are taught, energetic, and quick. If you are looking for slow and dreamlike Mozart readings, you should look elsewhere, but if you want these pieces to rest on the balls of their proverbial feet, then this will do you nicely. The playing by both the soloist and the Vienna Philharmonic on this recording is of superb musicianship and technical ability, yet never robotic or fast for the sake of showing off. Because of this balance, it makes the performances incredibly approachable for newcomers to Mozart or to the piano concerto medium.

Emil Berliner have wisely chosen to split this formerly single disc album into two LPs, and while those past retirement age may bemoan having to flip the records at more frequent intervals, their extra aerobic exertion will be rewarded with distortion free musical enjoyment far away from the hazardous inner groove.

The sound of these discs is incredibly transparent, and lacks some of the pesky overly reverberant qualities that plagued the previous two releases I reviewed. Gulda’s piano is large in the soundstage, almost larger than life, placed firmly in the center-left stereo image. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is certainly a contrast to some more hall-sound oriented productions from stereo’s golden age. In fact all the instruments are placed fairly close to the listener, but there is still a great amount of separation and image width, especially in the D minor concerto where there is so much frantic activity from all over the orchestra.

My only real complaint is that some of the large orchestral moments are dampened by a noticeably thin violin sound in the upper register, this sticks out like a sore thumb here mostly because the rest of the sound, from the piano to the winds to the cellos and basses, is so nicely balanced, to have this edgy and harsh sound come through during moments of energy and motion is distracting. I know it’s something I’ve complained about many times before from these 70s DG recordings, but it’s a real problem and prevents some of these fine albums from taking their seat among the best audiophile orchestral vinyl experiences. However while that caveat may be a down side to this double album, the merits far outweigh the demerits, and this is an expertly played, open and clear sounding rendition of perhaps Mozart’s best compositions for Piano and Orchestra. I would still call it an essential buy in the series.

Music 11/11

Sound 8/11

.png)