Radio Free Murmurs

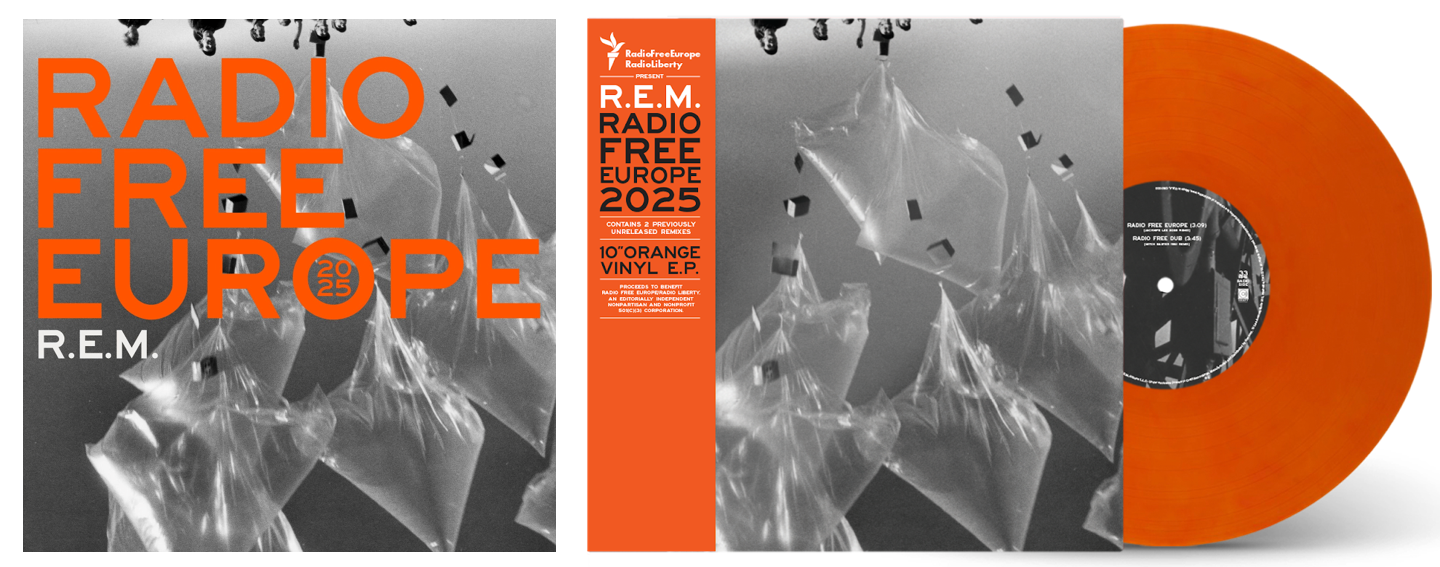

R.E.M release five-track benefit EP with previously unreleased tracks

When you pick apart the College Rock era, it’s probably fair to say that it dawns in a feisty little college town 70 miles north of the capitol dome in Atlanta. For all that’s been written about the New Wave to Indie Rock handoff, the fertile scene in Athens, Georgia was one of the principal arteries feeding the transition in the U.S. Fellow scenesters Pylon got there first with their "Cool / Dub" 7" released in April 1980, but the thousand copies of R.E.M.’s “Radio Free Europe” single was the initial crack on the industry’s windscreen that truly set the shift in motion.

Mitch Easter, was a guitar player and aspiring producer who knew next to nothing about the band when they turned up at his parents’ house in April of 1981 to record in their repurposed garage for their first session.

“They came up actually the night before and stayed at my house.” Easter recalls 44 years on. “We played records and I remember thinking, ‘This is great. this is what I want this recording thing to be like…total fun…playing records with people I never met before. That was really cool.”

The three tracks he managed to get down during that session, along with unreleased remixes from Easter and producer Jacknife Lee, are now available on a special 10” EP (from Craft Recordings) meant to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

The band strongly support the editorially independent organization, who’s federal funding has recently come under threat.

“Radio Free Europe’s journalists have been pissing off dictators for 75 years. You know you’re doing your job when you make the right enemies. Happy World Press Freedom Day to the ‘OG’ Radio Free Europe,” said R.E.M. bassist Mike Mills.

Easter, who went on to record the R.E.M.s next three releases alongside producer Don Dixon, took some time to recount those early sessions and how he went about capturing the sound of a band he hadn’t heard until they turned up on his doorstep.

///

Tracking Angle: So you weren’t at all familiar R.E.M. until they showed up at your studio?

Mitch Easter: I didn't know anything about them, but I had seen a poster for them at a club in Raleigh up here. And the poster had the sort of look of Michael Stipe art back then, you know, sort of mysterious and moody. And something about the poster made me and my girlfriend think that they must be kind of like Ultravox. And so they came in the studio, and they were not like Ultravox! But they were certainly good that day. They just always were. So, a session like that is automatically fun because as soon as you hear a playback it's like “Yeah, it's cool.”

TA: So it wasn’t particularly hard work?

ME: It was quick and dirty by design. You know they had the weekend and the goal was to produce something for a demo tape to give to clubs to get (them) booked. That's what everybody did. So it wasn't done with the idea that it would even be released, but you know, you still want to do something that's that you like. But it was just fast and fun. I felt like I was on their wavelength. I really liked them, and they seem to like me.

TA: What was the idea then for the dub remix you did at the time? Was it just an experiment?

ME: Yeah, it was. I had never seen the band live. They came in and recorded and not too long after that first session they were opening for XTC at the old 40 Watt Club (in Athens). I was a big XTC fan and it was a great opportunity to see both bands, so I just thought it'd be nice to have (something to bring) as a little present. So I just whipped that thing out and did it. It was just meant to be funny. It wasn't even really a proper dub mix, but it's “dub-ish” in a way because it's just messed up. And I don't know how long it took me, but not long. I might have even done it the afternoon we drove down there. It was just like an idea. But when I heard it like decades later, I thought “This is really kind of amusing.” And I guess (R.E.M. manager) Bertis Downs had never heard it until kind of recently. So that was kind of cool. But like everything I did in those days, somehow a cassette got duplicated by some people and it kind of got around, so some people knew about it. But mostly I guess it was unknown.

TA: Athens is virtually unrecognizable to what it was like back then, but what sort of first impression did Athens make on you when you got down there?

ME: I think I knew about the B-52s and maybe Pylon from New York Rocker magazine, which covered the band scene, but I had never been there until I went to that show I mentioned where I gave them "Radio Free Europe." When I went there, I thought, this is an amazing place. You could immediately feel there was a great vibe. Then I went back more often, and our band (Let’s Active) started playing down there too. But I didn’t know much about it. I didn’t realize there were already a million bands there. I had no idea.

TA: Most people who are familiar with the record know that it was truly a garage band setup, but how rough was it?

ME: The space was absolutely terrible. The house that I set up in was sort of an experiment—like, will this work? Will anybody come here? It was a 24’x24’ two-car garage that had been converted into a one-car garage and a children’s bedroom. We took out the children’s bedroom, removed the built-in furniture, cut a hole in the wall, and that became the control room. The rest was the two-car garage. It was really hard because it was a brick house built over concrete blocks, so it was very stout. There was a concrete floor pad, and everything was hard. The control room was square, so acoustically it was absolutely horrible. But I got used to it and ended up working in that space for 13 years…which is nuts.

TA: And what sort of equipment did you have in there?

ME: I had a basic but good setup, which was my concept in starting this thing. In those days, a lot of these indie rock studios would have half-inch 8-track tape machines, which they used to call semi-pro. They were good and sounded fine, but they weren’t the same as the big studio machines. I had a 3M M56 2-inch 16-track, and 16-track is still a very popular format because it sounds so good. Although that was the era when 24-track was really taking off, I was perfectly happy to have 16. So that’s what I had—the M56 16-track—and I had a 3M two-track machine that I got used from a studio in Atlanta. They were only about six years old then, but they were used machines. I had a Quantum (Audio Labs) 20-channel console, which was meant to be a professional console but was very simple and basic. At that time, I didn’t have any particularly good-sounding reverb. I had a spring reverb that sounded okay on some things. What we did back then for a bit of ambience was send signals out to the back porch of the house, which had a terracotta floor, so it was kind of reflective. We put a speaker out there and a microphone, and you could get a kind of reverb. It was a super simple setup, but I had some pretty good microphones, like an AKG C414, which is a proper studio mic. I still have a lot of this stuff—though not those tape machines—but I had them for years. I still have those microphones. I think I had two (Valley People) Gain Brain compressors and not much else. But that was enough to make a record that sounded at least fairly clear.

TA: The original single version has a very different sound to the version that was re-recorded for the album. Did you feel any pressure to deliver something different or specific at that point, knowing the song as well as you did?

ME: No. I mean I just think I understood why it was being re-recorded because it’s a good, catchy song. Famously, it got another mix before the single came out that nobody liked. I didn’t much like it either. Although it wasn’t drastically different from the one I did, I don’t think it was as good, and it just didn’t quite do what the song could do. So, I was happy about a chance to try to make it sound better. I think Don Dixon is the person who wanted to slow it down a little bit, and I kind of wish we hadn’t, but he was probably right because if people have a hard time taking in Michael’s words. At that speed they’re a little more understandable. Still, I kind of missed the slight punkiness of the single, but hi-fi wise, the one done on Murmur is a lot better sounding. The attitude back then was very “us and them.” If you were a classic rock band or a disco act, you had to be detested by the scene. I wasn’t quite that strong about anything like that, but I was down there with the attitude of the day: minimalism, avoiding overwrought stuff unless it was the cool overwrought of the day. Those guys definitely had a minimalist attitude about things too, so I don’t think they wanted us to slather production all over that track, even when we went to make the LP. I don’t think they would have gone for that. So it’s pretty simple.

TA: So ultimately you prefer the single?

ME: Well, I just wish we could combine them. I wish we could have the sonics of the reflection and the speed of the old one. That would be the version that I think I would like to hear.

TA: Do you think there’s a lot of stuff left in the archive from this period that might be included on a future release?

ME: Not really. That’s the great and terrible thing about those days. Tape was always kind of expensive, especially once it got to be two-inch tape. I think there are a lot more outtake versions of older records because they were recorded on half-inch tape, which was cheaper. So I don’t think there are alternate takes of much. If we didn’t get it, we’d erase the bad take. We were very efficient. I came out of a studio where bands were paying me with money they made the night before at the club, so our studio was cheap. That mentality was important to the scene then—it was morally superior to spend less money. It’s funny how some of those excess records have been rehabilitated. Everybody loves Tusk now, but at the time Tusk was the example of everything wrong. Fans of that era were generally on the side of minimalism. Besides, nobody was going to pay for us to have a whole lot of reels of tape.

.png)