Rewriting History: Deutsche Grammophon’s Groundbreaking “Original Source” Vinyl Reviewed

Cut Directly from the 4-Track Master Tapes, Deutsche Grammophon Mines Sonic Gold from its Legendary Back Catalogue

It is impossible to overstate the significance of this new series of vinyl reissues, first announced by Deutsche Grammophon in March. For the first time ever, a major classical label (if not, in the minds of many, the major classical label) was going to go back into its own archive and reissue —mastered directly from the original session master tapes (not a stereo mix-down) - all-analogue, 180gram vinyl, pressed to the highest standards at Optimal in Europe.

Classical enthusiasts like myself were left drooling at the possibilities. If everything was done right. (If you want to get into the detailed background of all this, check out my earlier article on this subject here).

The significance derives from a number of choices made by the label itself, and the mastering/cutting house of choice: Emil Berliner Studios (EBS).

First of all, this is essentially an in-house operation: EBS, originating within DG’s engineering and technical department, became a separate company when DG was re-structured in the late 2000s. Ever since, EBS has often functioned as DG’s de facto engineering department, even while it worked on a range of other projects, most notably the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s in-house record label.

In the past, audiophile classical music reissue campaigns on vinyl have been largely undertaken by specialist third-party companies licensing titles from the original rights holders. For example, in the realm of AAA vinyl reissues, you had the Chesky, Classic Records and Analogue Productions reissues of the early RCA Living Stereo catalogue. Mobile Fidelity and Alto licensed titles from EMI and Decca. For many years, Speaker’s Corner out of Germany concentrated on much sought-after early Deccas and Londons, then began to issue a few DG titles, and latterly some Columbia/Sony titles.

Between the ascension of CDs and the vinyl resurgence, the major label classical parent companies— now part of huge entertainment conglomerates —showed little interest in issuing vinyl versions of new or back catalogue titles. But as interest in vinyl began to grow around 10 years ago, DG was actually one of the first to dip its toe into these waters, though these releases tended to be mastered from digital sources.

However, DG began to adopt a more purist, audiophile approach to its vinyl reissues when it began licensing titles to the South Korean company, Analogphonic. These titles appeared to be sourced from original master tapes, cut AAA, both by EBS, and occasional outside mastering engineers like Kevin Gray. (I say “appeared” because labelling was rarely transparent, usually a sign that an analogue title was actually being mastered and cut from a digital file—though not always). Some of these recordings were digital to start off with, like the selected titles that appeared from Leonard Bernstein’s DG Mahler cycle. Analogphonic releases tended to disappear quickly, but sometimes their masterings reappeared as DG vinyl reissues.

DG itself also turned to some of its classic box sets, like the Karajan 1960s cycle of the Brahms symphonies, and gave them the audiophile vinyl treatment via EBS.

The other area where DG began to support truly audiophile values in back catalogue reissues was in a series of superb single-layer SACDs out of Universal Japan, which sounded like they had not only been remastered but also remixed from the original session or master tapes.

I go into all this in greater detail in my earlier article, but the essential takeaway is this. Via these reissues one was hearing a completely different DG house sound than hitherto: rich, 3-dimensional, with tremendous dynamics, a huge soundstage, and real tonal verisimilitude.

In other words, DG recordings— for the first time ever—were in the same ballpark as the acknowledged audiophile classics of RCA Living Stereo, Mercury Living Presence, Decca and EMI.

I am speculating here, but maybe it was this creeping success, the fact that these reissues were being greeted with joy and acclaim by those classical music lovers willing to pony up the substantial amounts of money to acquire them, that has led to DG taking the plunge into full-on, AAA vinyl reissues priced somewhat more moderately (albeit in limited editions—more of which later).

DG is not alone. In the realms of jazz and rock, in the last few years Blue Note, Craft/Concord and, most recently, Warner Bros./Rhino, have seen how successful vinyl reissues done right by companies like Analogue Productions, Sam Records, Intervention Records, and Speaker’s Corner can be, and instead of licensing out their catalogue to third-parties, are now keeping the whole operation in-house.

The winner is the consumer, because the number of records mastered and cut AAA has increased enormously just in a few short years.

Unfortunately, the truly audiophile vinyl reissue market for classical lovers has been somewhat lacking in recent years, so the arrival of the DG “Original Source” series couldn’t come at a better time.

Deconstructing the “Original Source” Series

The first surprise contained within the announcement of this series of reissues was the choice of titles. Most audiophiles (myself included) would have reasonably expected DG to play it safe, to go for the acknowledged earlier DG catalogue classics from the 1960s. There are seminal recordings here from the likes of conductors Ferenc Fricsay, Herbert von Karajan, Eugen Jochum and Karl Böhm; the Amadeus Quartet, Martha Argerich, Sviatoslav Richter, Pierre Fournier etc. And collectors know these are among the better sounding DG records because we all have our “large-tulip” pressings with that tubey magic to spare.

Instead, DG has chosen to focus on recordings from the 1970s, for one very important reason. Many of these sessions were recorded to four track master tapes, with two tracks dedicated to more of the hall ambience. At that time the label was thinking in terms of what the future might hold in terms of surround sound systems in listeners’ homes; in theory these recordings could be released as quadraphonic records (or some similar surround technology). But it never happened, because (I assume) DG felt the home reproduction technology did not meet their standards, or it wasn’t worth the extra expense, or there wasn’t a sufficient consumer base to warrant the investment, or a combination of the above.

But what this meant was that the master tapes, from which these “Original Source” releases are cut directly (with no intermediate step, analogue or digital), had four dedicated tracks, complete with room ambience: a potential game-changer sonically, even for a non-surround, stereo release.

The fact that this was even possible to do speaks to the extraordinary skill and expertise that EBS has been acquiring in its vinyl projects over the years. When the last team of in-house DG engineers—including Rainer Maillard—gathered to create EBS in the late 2000s, they managed to hang on to some crucial equipment.

Rainer Maillard

Rainer Maillard

Maillard, who had started working at DG as an intern in 1984, and who had witnessed all the trials and tribulations of the engineering department trying to maintain the highest technical standards while manoeuvring the switch to CD, then the collapse of the classical market and the restructuring of the company, takes up the story:

“In the first years (after management buyout) we (EBS) only did recordings for DG. Initially, they had their remasterings and vinyl cuts done elsewhere, but eventually decided to go with EBS again for special projects.

“As a fact of long DG history, the heads of the recording department were also in charge of operating the cutting lathes, because until 1945 a lathe was a recording machine. With our management buyout we took over the last DG VMS 80 and analogue tape machines for cutting. We thought about ways of using the lathe and since EBS emerged from the recording department, one idea was to go back to the tradition of using the lathe directly as a recording machine, instead of tape or a computer. So we started doing Direct-to-Disc recordings. As an engineer and producer I watched our cutting engineer Maarten de Boer while he worked on D2D productions. We immediately became aware of the strong relation between recording and target media (CD or vinyl). We discovered that recording for vinyl needs a different microphone setup than recording for CD. Engineers in the past had made different sonic decisions, knowing that they were producing music for LP and not a tape. I was fascinated and started to cut records by myself. Knowing this background, I wasn’t afraid to make sonic decisions and changes to new masters from other colleagues who were used to working with digital formats only.”

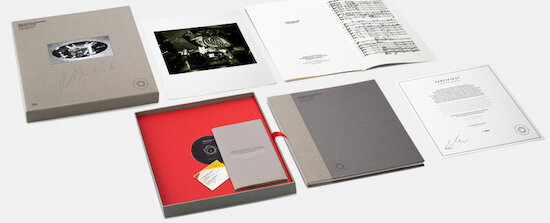

Here we have to turn briefly to the series of vinyl releases EBS produced in collaboration with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s own in-house label. An early benchmark was the “live”, direct-to-disk recording of the four Brahms symphonies with Principal Conductor Simon Rattle at the helm (a set which de Boer worked on with Maillard).

A huge success, this set now commands big bucks on the used market. EBS followed this up with a vinyl set of the complete Beethoven symphonies, again with Rattle.

Here the vinyl edition was not sourced from the same master tapes as the CD edition. The vinyl version was sourced from a more purist microphone set-up, similar to the famous Decca tree: a Blümlein pair placed above the conductor’s head, albeit still recorded to hi-res digital. Thus it conformed to Maillard’s ideas of miking differently for vinyl than for digital.

The pièce-de-résistance came in 2019, when EBS recorded, direct-to-disk, legendary conductor Bernard Haitink’s final concert with the BPO, consisting of Bruckner’s mighty 7th Symphony, one of Haitink’s signature interpretations. (MF provided one of several essays for the deluxe accompanying booklet).

This is an amazing sounding set, and it’s incredible to think it was recorded “live”, direct-to-disk, with no room for error, on such a special occasion. It speaks to the technical proficiency of the EBS team, headed up by Rainer Maillard (and including Sidney Meyer who has cut these new DG “Original Source” records).

Sidney C. Meyer

Sidney C. Meyer

With all this collective technical experience “in the can” (so to speak), EBS and DG’s decision to master and cut directly from the 4-track master tapes for the “Original Source” series must have seemed the logical next step, and a way to optimize the sonic quality of these releases.

But the other huge advantage to focusing on the 1970s era of DG recordings, and what makes these reissues particularly exciting and significant, is that this was a time when DG—in terms of repertoire and performers—was firing on all cylinders. The catalogue of this period is overflowing with riches, with great performers tackling unusual repertoire as well as the mainstream classics.

But sonically the 70s DG recordings rarely shone as did Deccas and EMIs of the same period. Unlike the 60s, there are no “large-tulip” pressings to hunt down. 70s recordings exist largely in middling vinyl pressings (with the occasional exception), and CD versions of differing sonic quality, depending on how they were mastered, and from what source. The piano sound in particular, from giants like Martha Argerich, Lazar Berman, Emil Gilels, and Maurizio Pollini, is frankly underwhelming.

What this all means is that listeners to 70s DG releases have never really heard what’s on the master tapes—until now.

The 70s was when I was buying records avidly, and my shelves are bursting with DGs of this period. These records sounded pretty good on standard equipment of the time, and surfaces were often quieter than those of DG’s competitors. But even on today’s entry-level audiophile equipment, the sonic shortcomings in these 70s pressings are self-evident.

Even with all the shortcomings, I and many others treasure these records for the performances and repertoire they contain, and the thought that we are going to have an opportunity to hear many of these in true audiophile quality, AAA sound, has been absolutely tantalizing.

So, like many of you, I have been waiting less than patiently to drop the needle on this first batch of “Original Source” releases. Let me say, upfront, my expectations have been more than fully met.

Mastering and Cutting the “Original Source” Series

Why do the original DG 70s vinyl pressings sound so inferior? One reason has to do with how the actual lacquers were cut back in the day. To head off potential problems, the DG engineers simplified and streamlined: they cut the actual grooves more narrowly, with less space available to accommodate a wider frequency response and stereo spread, which would, for example, convey more ambient sonic information. For the “Original Source” series, EBS widened the grooves, thereby allowing more sonic information to be cut into the record. They collaborated closely with Optimal in heading off any potential pressing problems caused by taking this approach.

The result is these new records sound enormous, with amazingly life-like dynamics and sonorities, conveying a 3-dimensional sense of the space in which the recordings were made. There is an ease to the presentation that I have rarely heard on a record before —especially when it comes to large-scale orchestral music.

Before I get into each individual release, here is some additional specific technical information. Quoting from the notes written by Rainer Maillard (Recording Producer and Managing Director of Emil Berliner Studios) and Sidney C. Meyer (Vinyl Cutting Engineer) included with each set of records:

“The (DG) recording department started producing for quadrophonic surround sound as early as 1970. The recording format was a 4-track analogue tape with left, right, front and rear channels. After the recording was finished, these 4-track tapes were edited in the studio at DG’s site in Hanover. The recording tapes were cut with scissors and reassembled with sticky tape.

“However, back in the day, there was no consumer format ready for quadrophonic playback, so DG was producing for the future. The label did release these recordings on regular vinyl LPs in stereo, of course. For this purpose, the engineers had to create a stereo downmix of the 4-track master tape. For the international distribution, DG then made copies of this copy and sent them around the world for local manufacturing.

“A tape copy can never sound as good as the original master tape, so the idea was born to make a product of the highest quality by using the original 4-track masters for lacquer cutting instead of the 2-track copies….

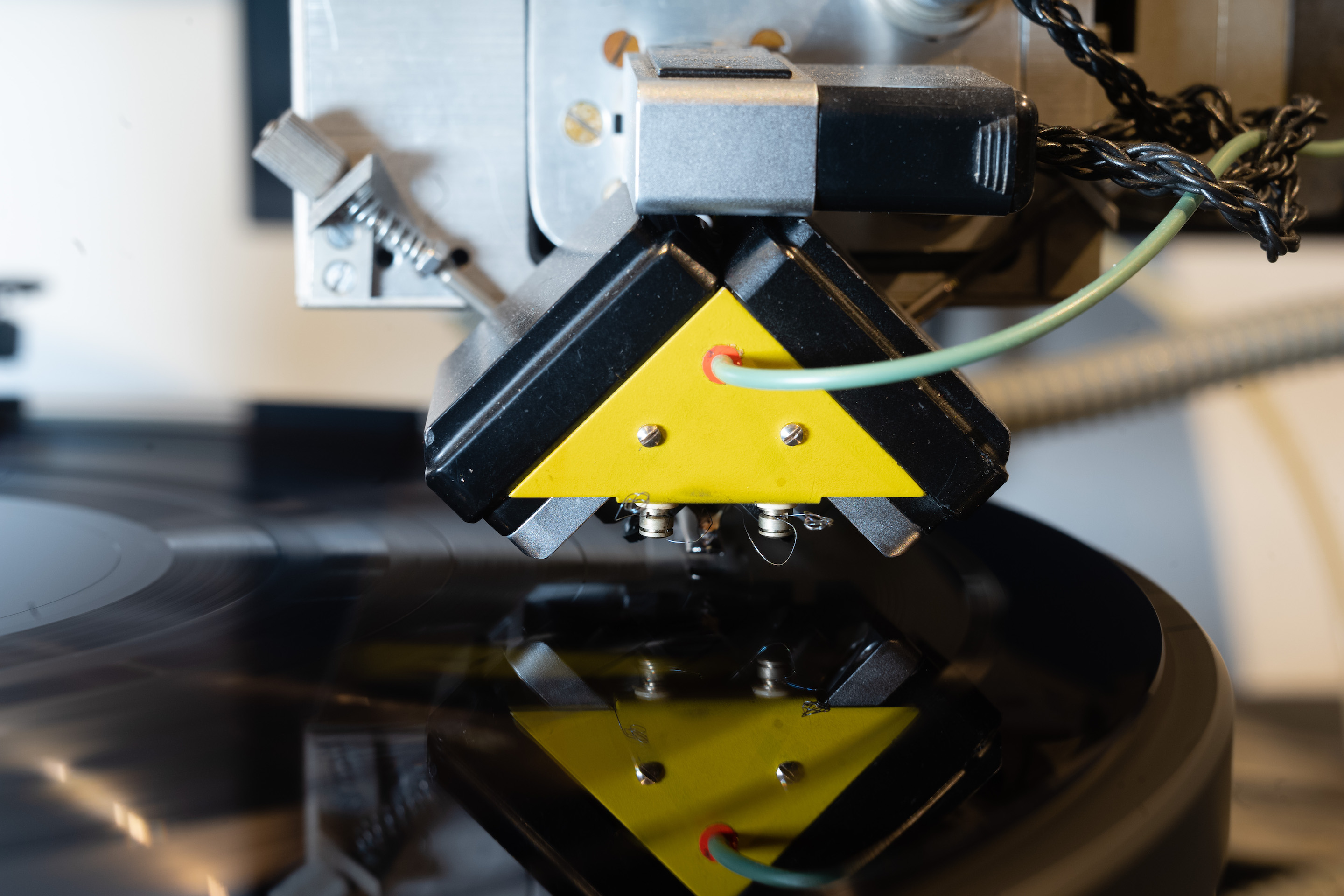

“… For the new releases, two technical aspects had to be taken into account: first, the 4-track tape is twice as wide as the usual 2-track tape; therefore we needed a special tape machine.

"It must be able to deliver a so-called preview signal, which allows the disc-cutting lathe to cut a perfect groove in the disc. Our tape machine had to be modified for this purpose and is probably the only one of its kind in the world right now.

"Second, we needed to mix the front and rear channels down to stereo in real time. A completely new, custom-built mixing desk was required for this project. Emil Berliner Studios have designed a passive mixer, which renders the highest quality without introducing any additional noise to the signal.

“The Original Source Series means: no tape copies used, no unnecessary devices in the signal path and of course no digital sound processing: pure analogue. This is the shortest possible way from the original master to the cutter head.”

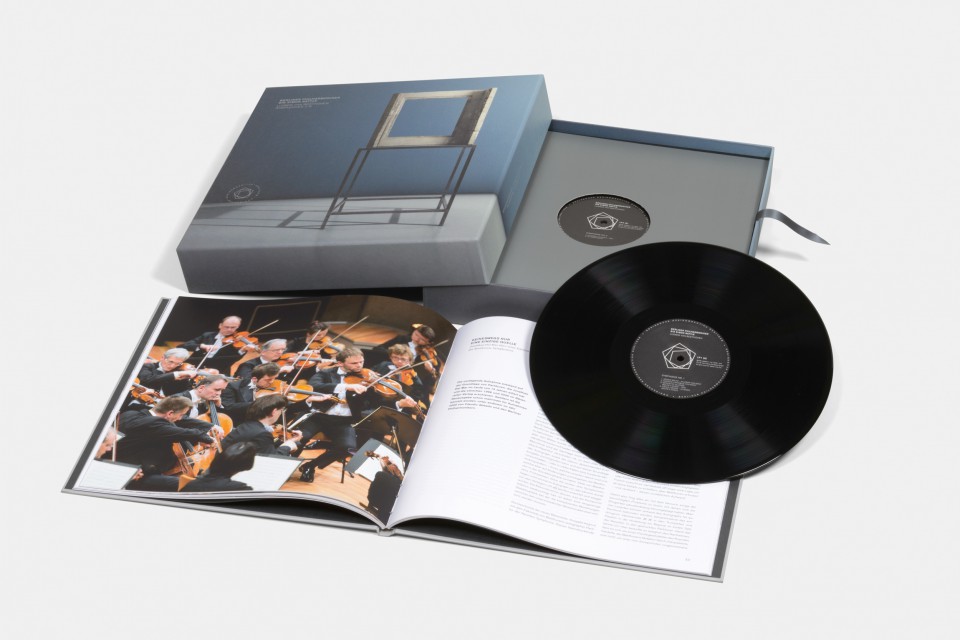

Visual and Physical Presentation

Each release comes in a gatefold jacket, whether or not it is a single or double LP release, on heavy cardboard stock (though not of prime Stoughton-level quality, but perfectly adequate, and thicker than original pressings). The gatefolds contain additional artist and/or session photos, plus photos of original session documentation or other visual material and essay translations. A loose insert contains the technical information quoted above, plus a photo of the original tape box documentation.

One departure from the original issues is the fact that the finish on the covers is matte rather than glossy. This is an interesting choice, no doubt in line with creating the sense of an “archive” release. I can imagine some collectors missing the characteristic DG high gloss finish of original pressings, but it did not particularly bother me, since the whole package comes in a Japanese-style re-sealable outer sleeve (with Original Source hype-sticker), which restores that glossy look when the record is inside the sleeve. The 180-gram platters come inside a black poly-lined sleeve.

The Records

All Original Source Releases Mixed by Rainer Maillard and Cut by Sidney C. Meyer, Pressed at Optimal on 180 gram vinyl

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan

(Original Coupling of Kindertotenlieder not included because it was not taped in 4-track)

Recording: Berlin, Jesus-Christus Kirche, February 1973

Executive Producer: Dr. Hans Hirsch

Producer: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer (Tonmeister): Günter Hermanns

Limited Edition of 2600

Music: 10

Sound: 10/9 (see below)

I decided to dive in at the deep end with this massive orchestral work. This was Karajan’s first foray into the music of Mahler, and has remained the most controversial of his Mahler symphony recordings by virtue, in part, of its sound quality—often diffuse and distant—both on the original LPs and the various CD re-masterings. Of all the recordings in this first batch of Original Source releases, here—I thought— I would get the greatest sense of what going back to the 4-track masters would yield.

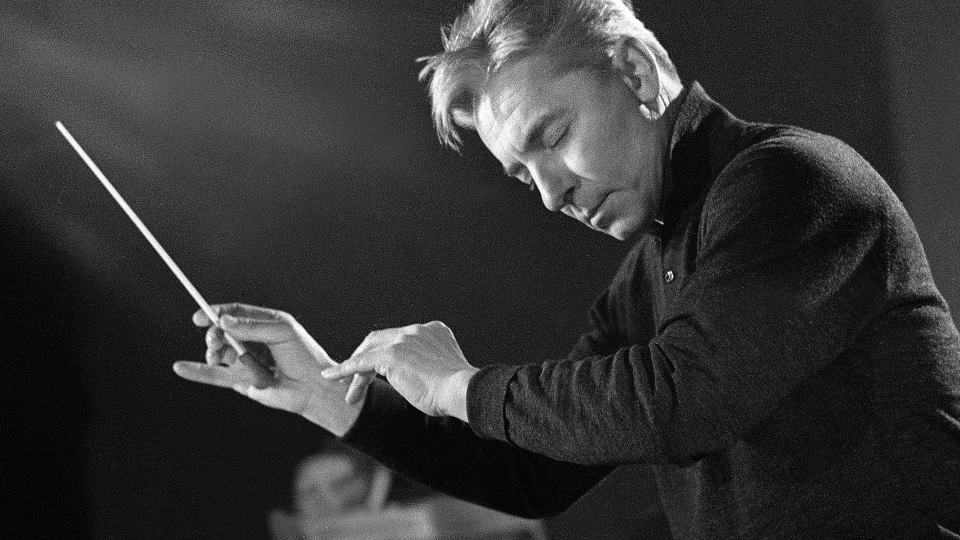

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan

A cynic might observe (and there are many Karajan cynics out there) that the conductor made this recording as much out of commercial pressure to get into the Mahler game as from his own inner artistic impulses. In 1973 Mahler was fast becoming the hot ticket in records and concert programming. It’s amazing to think that only some 10 to 15 years earlier his music was relatively unknown, despite some pioneering recordings by the likes of Herman Scherchen. At the time Karajan took the BPO into the studio to record this symphony, four complete major cycles had been recorded: by Bernard Haitink with the Concertgebouw Amsterdam on Philips; Rafael Kubelik with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on DG; and Leonard Bernstein with the New York Philharmonic on what was then still Columbia Records (now Sony). Maurice Abravanel’s dark-horse cycle with the Utah Symphony (much admired amongst audiophiles) was nearing completion on Vanguard (Symphonies Nos. 2 and 8 were reissued by Classic Records). Karajan’s supposed “rival”, Georg Solti, had just finished his own cycle for Decca with a combination of the London Symphony and Chicago Symphony Orchestras; his spectacular recording of the 8th, the “Symphony of a Thousand”, was issued in 1972, and is still to this day unrivaled in sound and performance (and was given the audiophile vinyl reissue treatment by King Super Analogue Disk).

In fact the truth is that Karajan came to Mahler with some trepidation, profoundly aware of the extensive preparation his music required to be rendered satisfactorily. The fascinating program notes for the “Originals” CD reissue of Karajan’s Mahler 5th include producer Hans Weber recalling the long gestation period for Karajan’s interpretation.

“His first concert performance….. in 1973 was preceded by a two-year phase of rehearsals, including an early trial recording….. Work on the Mahler symphony was spread over seven sessions during which Gundula Janowitz’s legendary version of Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs was also recorded. Karajan liked working in this way: he would spend an hour or hour-and-a-half on part of the Mahler and then devote the rest of a three-hour session to a Strauss song….

“Normally Karajan did not insist on approving the master tape of a recording personally, but in this case I remember him listening intensively to the tape near Cologne immediately after he had conducted the world premiere recording of Carl Orff’s De temporum fine comedia. The composer had come specially to hear the tapes of his own work, but was greeted by the sounds of Mahler 5 and the maestro’s loud exclamations of delight at the quality of his recording. Orff was not amused.”

Over the years Karajan— always obsessed by technology—was said to have had a lot of input into the sound of his recordings, beyond what was normally the province of conductors, and sometimes to the detriment of the final product. This recording of Mahler’s 5th was one of those often cited in this category, and whether or not Karajan actually did overrule the judgment of his engineers and producer in this case, this has remained a recording whose sound in its previous incarnations on LP and CD left a lot to be desired. (I actually asked Rainer Maillard to comment on this whole issue of Karajan interfering, and he said he never worked on any of the conductor’s sessions, though he did edit two of his last recordings. His sense was that Karajan was more hands off than his detractors have claimed, and my take is that this would not be the first time anti-Karajan prejudice has given rise to inaccurate reports).

But the fact remains, this was always a problematic recording. To refresh my memory, (and being a glutton for punishment), I put on my original German vinyl pressing, and was reminded instantly of why I so rarely play it. There is a certain diffuseness to the sound that seems to flatten out so much of the performance. I lasted about 3 minutes.

Now this symphony is full of what have come to be accepted as quintessential Mahlerian moments, and one of the most famous of these happens right at the beginning, in the opening Funeral March movement. A solitary trumpet sounds out a morose fanfare (in concert this has jackals amongst the audience waiting to see if the poor trumpeter comes a cropper). At the height of the trumpeter’s crescendo the rest of the orchestra comes crashing in at full blast, giving way to a slow, halting tread, over which the strings weave a deadening lament. It’s intensely theatrical, wonderful stuff, and was used tellingly in Ken Russell’s dubious biopic of the composer for moments where the composer was imagining his own funeral and being buried alive by his adulterous wife….. (ah, dear old Ken Russell….)

Anyway, underwhelmed as always by my original German pressing, I turned to the new “Original Source” version. First thing I noticed was there was a real trumpet sounding out, three-dimensional, precisely placed within the soundstage. His crescendo was visceral, and I could clearly hear when he was joined in unison by the other trumpets. When the rest of the orchestra came crashing in, it was a precise, vital sound (not an amorphous wash): I could hear all the layers of the different instruments. And BASS!!! Yes, real BASS!! In a Deutsche Grammophon recording! What a novelty!

And then, deep down in the bowels of the orchestra, that tam-tam adding just that little extra something to the texture. Undistinguishable on the original pressing, but giving a lovely frisson on this new version.

Did I mention the bass? It’s hard to express the joy of hearing the double basses so prominently, precisely articulated, giving that necessary grounding throughout the work, often joined by a cornucopia of low wind and brass. This is something large orchestral recordings often get wrong: the string bass. In a good concert hall (like Disney Hall here in Los Angeles) you may not always consciously hear it, but it’s there, anchoring the whole orchestra, and when you do notice it it can have the presence of a great jazz bassist. It’s vital to the pulse of a work, and on this “Original Source” pressing it is right there in the mix where it should be.

This “Original Source” pressing removes several veils from the recording. But the perspective remains mostly far back in the Jesus-Christus Kirche, DG’s favored recording location in Berlin for many years, even after the BPO's new Philharmonie concert hall was built (its acoustics remained recalcitrant for some years). The winds and brass seem almost isolated sometimes, well behind the strings, which themselves can seem distantly wispy in some of the more ethereal passages. But when the strings get really busy the perspective seems to change, and they can come at you like a wall of sound (something you will hear clearly in live recordings of the BPO under Karajan during this time period).

Ironically, in taking us closer to the master tape than in any previous incarnation, the “Original Source” pressing has allowed the listener to hear more clearly some of the balance manipulations carried out by the original recording engineers in real time. This is not a purist approach to miking and mixing. In fact this sounds like one of the more extreme examples of the interventionist approach that crops up regularly in the Karajan catalogue. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with that, it is simply an aesthetic approach that may not appeal to every listener, and I think it’s one of the reasons this particular recording will continue to have doubters (and it’s why my sound rating is a composite 10/9 - 10 for the sound on the record, 9 for the engineering choices we are hearing so clearly).

Do not get me wrong. In terms of capturing what’s on the 4-track master tape and bringing it to the listener on vinyl, this “Original Source” pressing is masterful. Every instrument sounds tonally right. There is never a hint of constraint in the dynamics. There is never the slightest hint that the vinyl itself cannot fully accommodate every nuance of what’s on the master tape. With an orchestral work of this magnitude, with these extremes of dynamics and orchestral palette, with massive clusters of sound coming at the microphones with full force, that is quite an accomplishment. The high strings have that lush, BPO sweetness that was so characteristic of the Karajan sound, and the famous Adagietto movement, made famous by Visconti’s film of Death in Venice, remains one of those great Karajan renditions. Each principal of the wind and brass emerges with his distinct timbre fully recognizable - albeit set mostly way back in the soundstage - and when Mahler and Karajan unleash the full force of those sections, this new pressing accommodates the frenzy with ease.

Just how remarkable an accomplishment this pressing is was highlighted when I turned for comparison to the EBS mastered single-layer SACD, which hitherto I felt to be the definitive version of this recording. The SACD lacked the full 3-dimensionality and organic quality of the new vinyl; it felt more like an extremely accurate reproduction rather than the thing itself.

The interpretation, for all its many felicities, remains for me less compelling than Karajan’s 6th and both versions of the 9th. (I am especially hoping that the 6th exists in a 4-track master, ready to be transferred for this series). For vinyl-loving audiophiles who share my reservations, I will suggest checking out the Georg Solti or Zubin Mehta versions of the symphony on Decca, or of course the fabulous Bernstein on DG, recently given the best possible makeover on vinyl by EBS, though handicapped by being a less-than-perfect early digital recording.

Franz Schubert: Quintet for Piano, Violin, Viola, ‘Cello and Double-Bass in A major, D.667 “The Trout”

(Original Coupling of Schubert’s Quartet Movement in C Minor, D. 703, not included because it was not taped in 4-track)

Emil Gilels, Piano

Norbert Brainin, Violin

Peter Schidlof, Viola

Martin Lovett, Violoncello

(all members of the Amadeus Quartet)

Rainer Zepperitz, Double-Bass

Production and Recording Supervisor: Günther Breest

Recording Engineer: Klaus Schiebe

Recorded: Konzerthaus, Turku Finland August 31st - September 4th, 1975

Limited Edition of 2300

Music: 11

Sound: 11

There’s a reason why certain classical works remain the evergreens, subject to endless recordings which nevertheless music lovers are happy to buy over and over again in multiple versions. And Schubert’s Trout Quintet, so named for the fourth movement’s series of variations on his song Die Forelle, remains probably the most popular work in the entire chamber music repertoire.

The reason why this work is so adored must start with its fecund streak of melodic invention, which reaches its apex in that fourth variation movement. People hum this tune having no idea where it comes from.

But I think another reason why this work is so popular is its singular instrumentation, a most unusual combination of piano with—instead of just a standard string quartet—violin, viola, ‘cello, and double bass. The double bass adds a jocular quality to the piece, and in the right performance can evoke a vision of a slightly tipsy Falstaff burbling along to keep the proceedings from getting too serious.

Caricature of Schubert (r.) and singer Johann Vogl, attributed to composer's friend, Franz von Schober

Caricature of Schubert (r.) and singer Johann Vogl, attributed to composer's friend, Franz von Schober

Franz Schubert, himself physically and socially ungainly, nevertheless wrote music of such humanity, charm, and often wistful sentiment, that it’s almost impossible not to smile at his inventions (although he could also go very dark indeed). In many ways he was the perfect bridge between the Classical and Romantic periods, his music self-effacing on the surface, more complex both aesthetically and emotionally once you start to probe more deeply. His music flourished in the more intimate settings of café society, and it was in such establishments as well as private homes that he found his most loyal audiences. His vast catalogue of songs remain the touchstone for the form. When you consider he was dead at 31, the range and maturity of his works is awe-inspiring. Bernard Levin, the great British journalist and man of letters, who was also a passionate music lover (and Wagner apostle of the first order), religiously attended the Hohenems Schubertiade Festival devoted solely to the composer’s works every year. In his paean to the Festival published in The New York Times in 1983, he described a memorable performance of the Octet:

“And in the final ''Allegro,'' where Schubert throws away his scabbard and takes Heaven by storm, the nightingales, which abound in this part of Austria, joined in. Perhaps they did not sing strictly in tune, but by then that did not matter, for the nightingale is the most Schubertian of living creatures, and its song conveys the same truth that he does, which is that nothing bad matters, and everything good does.”

The same spirit suffuses the Trout Quintet. Schubert embues the work with an almost folkloric quality, writing for the strings in a manner that evokes instruments like the cimbalom, closely associated with Eastern European folk music (and used so memorably by Enescu and Liszt in their orchestral Rhapsodies). Of course the piano immediately places the work within bourgeois and upper class society, but again there’s that irreverent double-bass bumbling along in the lower register to remind everyone not to take themselves too seriously.

Since it was first issued in 1958, the Decca recording of this work with Clifford Curzon and members of the Vienna Octet (drawn from the ranks of the Vienna Philharmonic, including the orchestra’s legendary concertmaster Willi Boskovsky, famous for his Decca recordings of the Strauss family waltzes) has been the benchmark version. It is overflowing with that quintessential Viennese charm and lilt, and the recorded quality is in the best Decca tradition. I treasure my first Decca pressing; a much cheaper and fine option is the Speaker’s Corner reissue.

So when this DG recording first appeared it was up against stiff competition. On paper it is a more overtly Germanic rather than Austrian affair—which is to say it is more overtly “serious”. Emil Gilels, a titanic product of the Soviet school of pianism, was more associated with Beethoven, Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff than Schubert. The Amadeus Quartet, from whose ranks the three upper string were drawn, was the de facto house string quartet of DG, and again more associated with Beethoven and Mozart (though they did record the principal Schubert quartets and the exquisite String quintet). When it came to recording all Schubert’s string quartets in the 1970s, DG assigned that to the Melos Quartet.

I had had this recording of the Trout Quintet in my collection since it was released, being an inveterate Gilels fan since I saw him play live at my school when I was a teenager. (I sat onstage behind him, some 10 ft. from the piano keyboard, and it remains to this day the most memorable piano recital of my life). But I had no strong memory of playing this record. Hearing of this impending release, I dug it out, gave it a good clean, and took it for a spin.

I couldn’t believe my ears. The instruments sounded like they had been smothered in blankets, the sound was that attenuated. The piano was tinny, the violin thin and reedy. Half the time it didn’t sound like there was a double-bass there at all. It also sounded like the record might have been mastered out of phase, if such a thing were possible.

So naturally I was especially keen to hear this “Original Source” pressing.

My high expectations were more than met—they were thoroughly exceeded. A more natural sounding, “you’re in the room” chamber music recording I have rarely heard, with the piano full-voiced, the strings sweet and vibrant, and that Falstaffian double-bass deliciously present. In fact the quality of the pressing is so good that I could clearly hear the violin was playing metal strings (the norm at that time). Alas, Mr. Brainin’s presence is so forthright that I am reminded of why I’ve never been that big a fan of the Amadeus Quartet recordings: he has that wide, slightly too wobbly vibrato (again typical of most string players of the period) that for me teeters right on the edge of making me feel queasy. Well, such judgments are strictly down to personal taste.

What of the performance as a whole? Well, it’s definitely a more overtly Germanic take on the work than the Curzon/Vienna Octet version, which smiles and winks more. But boy do they play the hell out of this. That bold, rich Gilels sound drives the performance, but it’s never overpowering. There’s a real sense of give and take, of friends playing together. And the sound is so effulgent, so present, that it quite takes the breath away. You are right there in the room with the players.

As with all these “Original Source” pressings, there is an effortlessness and naturalness to the presentation that makes all the technology delivering the audio disappear. It’s utterly beguiling, which Schubert in his lighter vein should be. Makes me want to pour another cup of coffee to have with that third slice of Apfelstrudel mit Schlagsahne. Delicious!

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Carlos Kleiber

Production: Dr. Hans Hirsch

Recording Supervision: Hans Weber

Recording Engineer: Klaus Scheibe

Recorded in the Musikverein-Saal, Vienna: November 26th - 29th, 1975, and January 16th, 1976

Music: 11

Sound: 11

We’re on much safer ground here, in terms of the recording quality on the original master tape, than we are with Karajan’s Mahler 5, and this “Original Source” pressing is, frankly, a thing of wonder, representing a massive improvement in sonic quality over any previous version of this classic version of Beethoven’s 7th.

I will never forget the first time this then 15-year-old put his brand new copy of Carlos Kleiber’s legendary recording of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony onto his turntable and let it rip. It was then, in 1975—and still is to this day—one of the most exciting performances of anything ever caught on tape. There are many other fine 5ths, and one of my favorites is Solti’s 1959 account with the Vienna Philharmonic, a magical early stereo Decca recorded in the incomparable acoustics of the Sofiensaal.

But Kleiber’s 5th is on a whole other level of intensity (which is saying something when you are comparing his conducting to that of “the screaming skull”, as Solti was affectionately known in music circles). Kleiber makes you hear the work afresh every time you spin it—even to this day.

So when Kleiber’s follow-up, the 7th Symphony, came out a year later, expectations were sky high for another truly revelatory listening experience. That didn’t happen—how could it, really? I remember reading the reviews at the time, with critics almost apologizing for not finding this record as compelling as the first.

Well, with time, this account of Beethoven’s so-called “apotheosis of the dance” (in the words of Richard Wagner) has found its place in the pantheon of great recordings. I remember when it came out that one of the qualities that seemed to keep it from achieving the full-on greatness of its predecessor was the sound being less immediate, almost less “integrated”— if that makes any sense. This is an impression that has stayed with me over the years, even through a subsequent, improved incarnation on Speaker’s Corner, so again I was very eager to hear how the recording itself might have benefited from the new mastering and pressing by the folks at Emil Berliner Studios.

After briefly re-auditioning my Speaker’s Corner copy, I dropped the needle on this “Original Source” pressing. Can I use the word “gobsmacked” in a respected audio publication such as this? Well if that’s what I was, then hell yeah!

I was now in great danger of getting so used to this whole other level of vinyl excellence every time I put on one of these “Original Source” pressings that I briefly contemplated throwing half my record collection in the dumpster. When you hear music presented this truthfully—or rather I should say that when you hear what is on the master tape so clearly reproduced—without any kind of mediation between you and what’s on the original recording, anything short of that starts to sound inadequate.

So here we are, sitting more or less where the conductor is, with the VPO laid out in front of us. I feel far more comfortable with this more immediate, drier aural presentation than the more distanced but also manipulated perspectives of Karajan’s Mahler 5. On this Beethoven 7th I can clearly hear when certain winds and brass are being spotlit, but the overall effect is far more coherent aurally than on the Mahler. As always with these “Original Source” releases, the dynamics and instrumental timbres emerge seemingly unmediated by technology. You hear what’s on the original master tape, for better or worse.

Which means that the performance is left to emerge more organically, and it’s a terrific one. Rhythms are precise, well sprung. The orchestra, playing a work it’s played a thousand times, sounds thoroughly galvanized. And while this isn’t the VPO sound we know from Decca records of the late 1950s and early 60s, it is still very definitely that unique string sound, (sweeter than Karajan’s Berlin Philharmonic), and that burnished wind and brass timbre that belongs so completely to Vienna. And, as with the BPO’s Jesus-Christus Kirche in Berlin, again we clearly hear the acoustic space of the Musikverein Saal where the music is being played. You hear everything - effortlessly.

Igor Stravinsky: Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring)

London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado

Production: Rainer Brock

Artistic Supervision: Günter Hermanns

Recording Engineer: Joachim Niss

Recorded in Fairfield Hall, Croydon: February 7th - 9th, 1975

Music: 10

Sound: 10

Stravinsky’s revolutionary masterpiece, one of the principal works to usher in 20th century modernism in music, has long been the work of choice for record companies wanting to demonstrate just how visceral and explosive they can make their recordings sound. Hi-fi dealerships the world over have reverberated to numerous “demonstration quality” recordings of this evergreen spectacular, once the bane of orchestras for its fierce technical challenges, now more easily tackled by today’s highly accomplished players.

It’s a work often presented as a calling card for a young maestro eager to make his mark. Here in Los Angeles performing the Rite was almost an annual ritual for the long-standing Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Esa Pekka Salonen, though he was outdone on his home turf by a searing performance I heard by Valery Gergiev with his own Kirov Orchestra on one of their many visits to La-La Land before the conductor became person non grata in the West for his close affiliation with Vladimir Putin.

On record too, a new recording of the Rite is often issued to put a new young firebrand up front and center before the record buying public. Think Riccardo Muti’s arrival as Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1979, with EMI issuing two still phenomenal records of orchestral spectacle: a coupling of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition with Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite, plus a record of the Rite (both were reissued on vinyl by Mobile Fidelity).

Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado

In 1975, the Italian Claudio Abbado was well on his way to becoming one of the most distinguished (and beloved by musicians and audiences alike) conductors of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His first couple of records - issued in 1967 on Decca (with the LSO in Prokofiev, and the VPO in Beethoven’s 7th, no less) are very fine indeed, but a new contract with DG quickly resulted in one of the classics of the catalogue: Martha Argerich’s recording of the Ravel Piano Concerto, and Prokofiev’s 3rd Piano Concerto, with Abbado conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

Abbado continued to record with the LSO for both DG and Decca, including fine Rossini operas, plus more challenging repertoire by Berg and again more Prokofiev. In 1975 they cemented their relationship when he was appointed the LSO’s Principal Guest Conductor, and DG embarked on what became a benchmark series of Stravinsky recordings, including the lesser known but glorious neo-classical ballet Jeu de Cartes, and the complete version of Pulcinella. These records were further distinguished by their fantastical original cover art by Peter Wandrey, whose work for DG was always very special indeed.

I bought all of these Stravinsky records the moment they came out, and Abbado’s recording of the Rite was long a favorite, along with Muti’s on EMI with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Michael Tilson Thomas’s with the Boston Symphony on DG.

But when I started to upgrade my system to something along more audiophile lines in the 90s, I discovered my original German pressing of the Rite was severely lacking. It sounded artificially spotlit, with little sense of a coherent soundstage. I pounced on a rare Japanese 45rpm pressing I happened upon a few years ago, and it was definitely an improvement, but the whole thing still sounded artificial, a studio concoction.

So when I learned Abbado’s Rite was going to be one of the first of the new “Original Source” reissues, I was very excited to see what magic Rainer and Sidney had wrought on this personal favorite.

I was not disappointed. As with the Mahler, this inhabits a huge soundstage, but the overall effect is more coherent, with various spotlighting moments more integrated into the sound picture. The perspective is from around three quarters of the way back into the hall. But we never lose detail, and the dynamic range is huge.

As with the Mahler and Beethoven recordings, I delight in hearing the most subtle shadings of instrumental timbre and phrasing. When was the last time you heard the Rite on record and you could pick out exactly when the timpani versus the bass drum was playing? The woodwind solos and clusters of the quieter openings to parts one and two have such character and finesse. And hearing those lower wind instruments explore their nether regions is its own special treat.

As with the Mahler and Beethoven records, I can clearly identify the specific orchestra I am listening to. This is the LSO I grew up with, releasing one terrific record after another with their Principle Conductor, Andre Previn. The Rite was recorded only a couple of years prior to them recording the soundtrack to Star Wars. This was a lean, mean music machine, able to play anything thrown at it in concert and in the studio with aplomb and verve. It was the perfect band for Stravinsky, and I am hoping against hope that some more of these Abbado/LSO collaborations will be coming to us in the “Original Source” series (especially their wonderful Pulcinella).

This performance of the Rite is more about precision and accuracy than it is about subjective thrills (for those Muti is your man). This doesn’t mean the big moments disappoint, it’s just they are more part of a whole. For those reasons it’s a performance that wears well over repeated listenings. Do not get the idea that Abbado skimps on the spectacle; on this “Original Source” pressing you get a full-on orchestral workout, going from icy cold to burning hot, often within seconds. Of all the “Original Source” releases in this first batch, this is the one to take to audio shows and try out on megabucks systems. This is a racing car tuned to perfection, taking the curves at full speed with no sense of strain.

Turning to the single layer SACD that EBS mastered a few years ago, I had the same reaction as I did to the Mahler 5. The new vinyl simply sounds more organic, more natural. Put this down to the difference between analogue and digital.

One Caveat….

Before I wrap things up, I do have one significant bone to pick, and one request to make, and that concerns the number of records in this series that are going to be pressed. Each LP is listed as part of a Limited Edition, and the total numbers listed range only in the couple of thousand range. As these first titles, and then future ones, have been announced, they have sold out, but fortunately in subsequent days have reappeared as being available to pre-order or buy.

Now I am not going to tell DG how to conduct their business, or how to make money, but I feel pretty strongly that these records should never go out of print beyond having a particular production run become depleted. These are important classical titles, and they deserve to be available for anyone to buy, more or less in perpetuity, especially when they so vividly capture the true sonic signature of the label. The price point is fair (and thank you DG for not simply doubling the price on 2LP sets). Please, DG, find a way to keep these records in print for all those who are going to eventually hear just how great they are, and want to buy a copy without being fleeced on the second-hand market.

In Conclusion

Anyone listening to these four releases is privy to a unique experience. For the first time ever, we are hearing—as near as it’s possible to hear in a home environment—what DG recordings actually sound like on the master tape, and it’s a very special treat.

Over and over again I found myself remarking: “I had no idea my system sounded so good”. The music emerged effortlessly, with no sense of strain: big when it was big, small when it was small, but always lifelike, not hi-fi. Mahler, the BPO and Karajan; Beethoven, the VPO and Kleiber; Stravinsky, the LSO and Abbado; Schubert, the Amadeus and Emil Gilels (a special treat to hear this pianist sound so present)—all right here in my living room.

With this series, DG has effectively set out to rewrite the sonic history of the label, and with this first batch of records it’s clear they have succeeded beyond, I suspect, what anyone thought possible. (Though I have a feeling Rainer Maillard may have had a pretty good idea of what was achievable).

There is a delicious irony in all this: that it was the revival of interest in the lowly LP, and belief in the analogue process, that enabled this return to the “Original Source” to happen. The supposedly “low-fi” vinyl disc trumps all the new fangled digital stuff, and turns out to be the best medium to demonstrate just how great-sounding hundreds of DG recordings sitting in the archives really are.

Goliath, meet David.

That this has happened at all is somewhat miraculous; the fact that it has happened within a vast entertainment conglomerate—not a small boutique label—is almost unbelievable. So this is all down to a few motivated individuals who saw an opportunity and, to their great credit, and for us listeners’ huge benefit, took the risk and seized the day.

Projects like this don’t happen overnight, and they are only able to happen at all because of people who really care passionately about the work they do. Speaking now as someone who has been buying records, and especially DG records, for some 50 years, what I noticed some 10 to 15 years ago was that the folks at Emil Berliner Studios, and I will single out Rainer Maillard, really cared about sound, and representing what they heard in the concert hall, and on master tapes, to the best of their ability. And I also noticed that Mr. Maillard strongly believed in analogue vinyl records as the very best medium for delivering not only the best sound off a master tape, but also the best way to communicate that incalculable magic that makes you want to turn the volume up. His various projects with the BPO’s new record label resulted in sold-out runs of limited editions. New vinyl editions of classic DG recordings began popping up on boutique labels, again selling out quickly. It was hardly surprising that Michael Fremer was out there promoting and supporting Mr. Maillard’s work whenever possible.

Then I started to see a new, younger generation of engineers turning up in the background of photos of these vinyl projects in progress. Prominent amongst these was Sidney Meyer, who has cut these “Original Source” records to perfection. This is no surprise to anyone who has heard her work on the earlier direct-to-disc limited edition of Ma Vlast recorded by the Bamberg Symphony. (For those of you who don’t know, she also worked with Kevin Gray to hone her skills).

Well, as this “Original Source” project began to come into focus, we can assume that someone within DG—or several people—saw the potential in this project and gave the green light not just to go ahead, but to do it without cutting corners, to get it done the best it can be. The records credit Johannes Gleim and Meike Lieser as Product Managers, and no doubt they played a key role. Music lovers, classical collectors and audiophiles owe a huge debt of gratitude to everyone who helped make this project happen.

Vinyl lovers who are new to classical should not hesitate to acquire all of these “Original Source” editions to supplement the wonderful Analogue Productions Living Stereos (and a few other choice titles from other labels), which are completely different in sound and method. You will have the beginnings of a great classical section in your collection. Seasoned collectors, do not hesitate. Even if you question the recording approach embodied in the DG 70’s catalogue, you owe it to yourself to hear these records.

And there are many more amazing records on their way in this series. Of the titles already announced (listed at the end of this article) I am especially drooling at the Beethoven sonatas and Brahms piano concertos with Emil Gilels, titanic performances that are seriously compromised on my old vinyl pressings; and Abbado's benchmark Debussy and Ravel from Boston. I've never heard Ozawa's Symphonie Fantastique, but that conductor's Boston legacy is full of gems that have never gotten their sonic due, and to hear them in rejuvenated sound is a more than tantalizing prospect. I also can't wait to hear the Friedrich Gulda Mozart piano concertos, again performances I am not overly familiar with.

It’s an odd, almost schizophrenic moment for the classical record industry. On the one hand, you have the small, independent classical labels putting out many fine recordings of all manner of repertoire on CD and SACD (and on various digital and streaming platforms), while on the other hand you have the majors making individual titles in the back catalogue impossible to buy while also issuing endless boxes of treasures from their archives. Yes, it’s great to have these box sets available (while they remain, all too briefly, in print), but they vary enormously in terms of sound and the quality of accompanying documentation.

And then, in the midst of all this, and in an uncertain market for classical product, one of those majors, Deutsch Grammophon, has chosen to take a bit of risk and do something different, something I think no one saw coming: to go (forgive me) back to the future. Back to the basics. Respect the original vision and mission that brought the label into existence at the beginning. Respect the intent of the original artists and engineers who lavished care on their craft and art. Respect the sound on the original master tape. Respect the medium that best conveys all those intentions and ideals. Respect every aspect of the mastering, plating, pressing and packaging of the product, and do it all to the very best of your ability, at a price point that is fair.

I really, really hope that Decca and Philips (like DG, part of Universal Music), Warner (which owns EMI) and Sony (Columbia) - all of which have countless treasures sitting in their vaults - are paying close attention. This is the way to mine your back catalogue. No vinyl mastered from digital files pressed at dodgy plants. Respect your heritage, and respect the consumer whom you may be surprised to learn is willing to pay extra for true quality over “good enough”. Who knows, you might find yourself making a bit of money along the way.

Where Deutsche Grammophon leads, you can follow.

Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer

Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer

Upcoming “Original Source” Releases:

All the records I have reviewed above are currently available to purchase either directly from DG, or from the usual retailers in the U.S. and elsewhere.

DG has already announced the next two batches of releases, and there are some mouth-watering titles included. The release dates are global, but if you are ordering from some U.S. retailers there seems to be a little lag time before they are made available.

August 4th:

Brahms: Piano Concertos with Emil Gilels, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Eugen Jochum

Brahms: Piano Concertos with Emil Gilels, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Eugen Jochum

Debussy: 3 Nocturnes

Debussy: 3 Nocturnes

Ravel: Daphnis et Chloe, Suite No. 2; Pavane

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado

Verdi: Messa da Requiem

Verdi: Messa da Requiem

Soloists, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan

September 29th

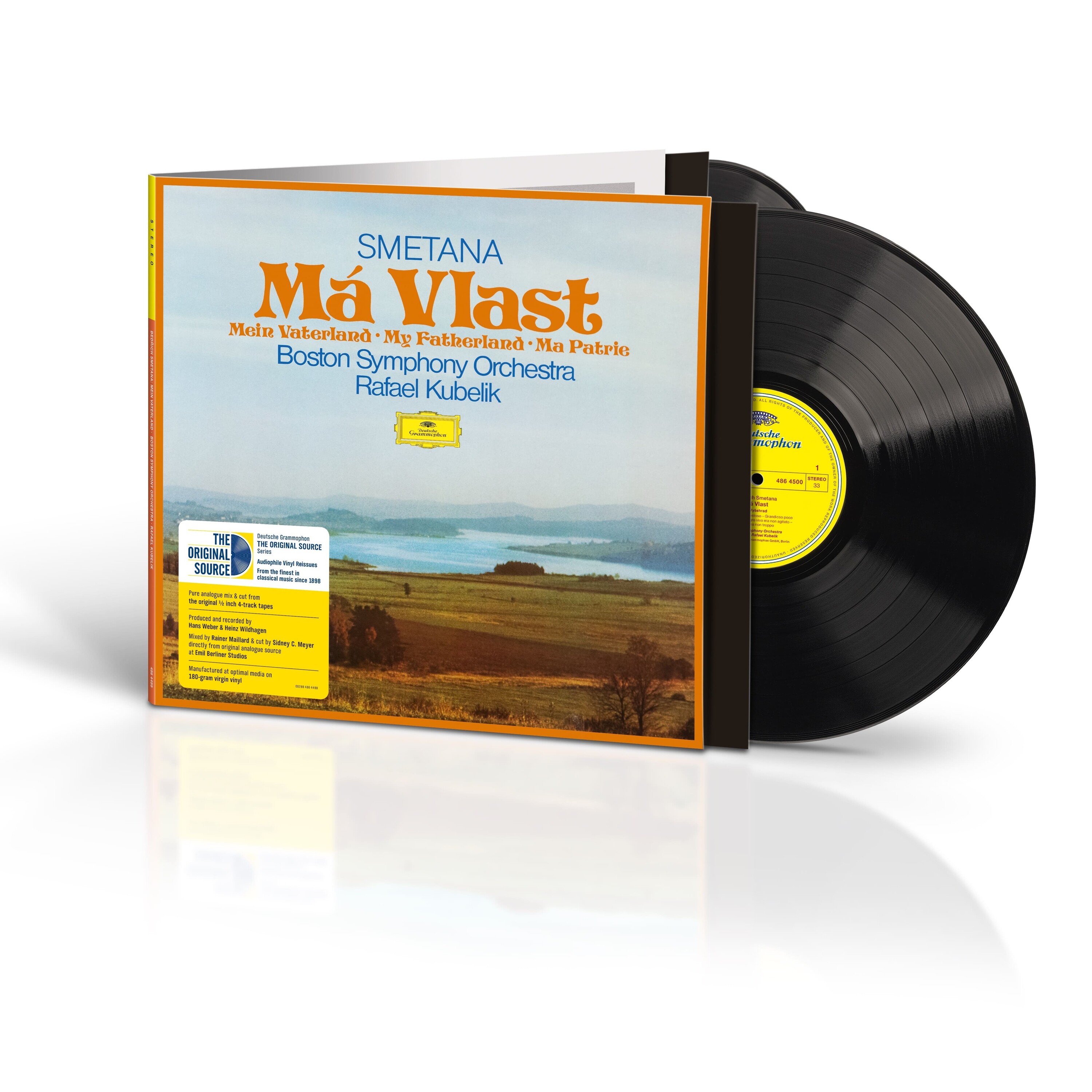

Smetana: Ma Vlast

Smetana: Ma Vlast

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Rafael Kubelik

Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 25 and 27

Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 25 and 27

Friedrich Gulda, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 25, 26 “Les Adieux”, and 27

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 25, 26 “Les Adieux”, and 27

Emil Gilels

.png)