Will We Ever Understand Sly Stone?

His new memoir ‘Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin)’ brings up more questions than answers

On a Sunday night in April 2010, a mostly reunited Sly & The Family Stone took to Coachella’s Mojave Stage. Despite Sly’s notoriety for missing his own shows, audience—and perhaps promoter—anticipation was high after a short preceding run of reunion shows went fairly well. That night, however, Sly wasn’t feeling it. He shortened songs, ranted about legal problems with a former manager (who promptly sued him back for these “slanderous” comments), played new songs from his laptop, and abruptly left. His bandmates, some of them his actual family, looked concerned but not shocked; unfortunately, this wasn’t uncommon with him. Sly’s performance might not be the most infamously disastrous Coachella comeback ever, but it became yet another sad story of his later years. What happened?

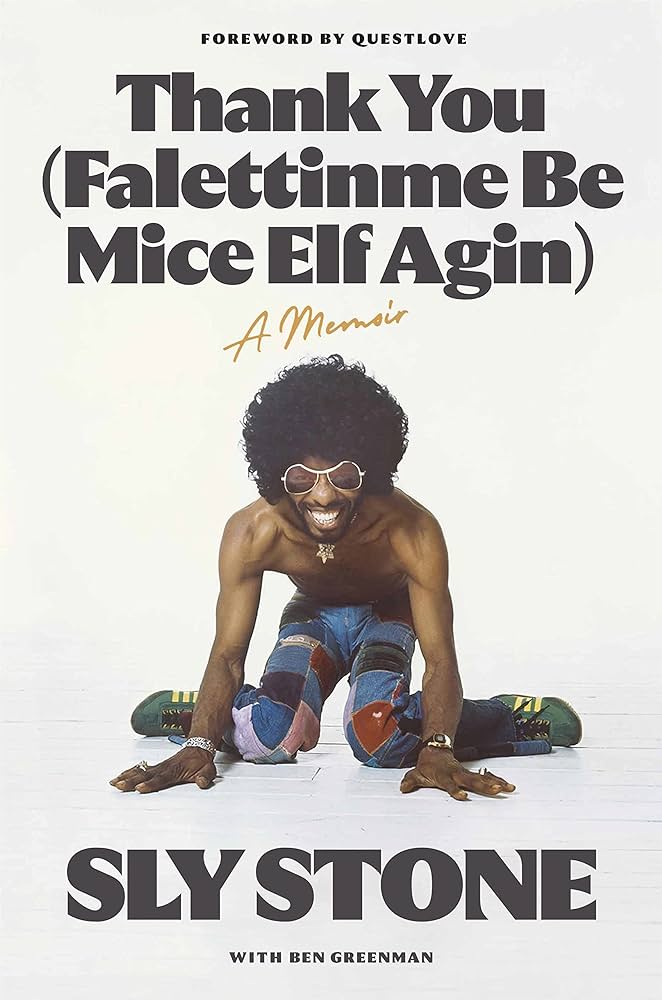

Sly Stone’s new memoir, Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin), purports to tell all. Co-written with Ben Greenman (co-writer for George Clinton, Brian Wilson, Questlove, and others) and once-girlfriend, now-manager Arlene Hirschkowitz, Thank You is the first time the now 80-year-old, interview-reluctant artist has told his side of the story: his formative years, his rise to superstardom, and the long decline that followed.

“Sly has lived a hundred lives,” Questlove writes in the book’s foreword. And by that metric, he’s nearly died about a hundred times—it’s amazing that Sly is still here to tell the story, even though he now struggles with COPD and is too frail to make music. Yet Thank You’s roughly 270 pages of narrative, based on over 300 interviews with Greenman and Hirschkowitz, reads like a Wikipedia page told in the first person, a broad but shallow portrait of his life and career.

A brief primer for those unfamiliar: Sylvester Stewart, born 1943 in Denton, Texas and raised in Vallejo, California, quickly became the musical talent of his already very musical family. Gifted with innate understanding and proficiency on multiple instruments, he played and sang in a few bands, produced other people’s records, and became Sly Stone, a DJ for San Francisco’s KSOL. With some family members, friends, and friends’ family, he formed Sly & The Family Stone, a mixed-race, mixed-gender band whose optimistic message and amalgamation of rock, soul, and funk fit perfectly with late-1960s counterculture.

By 1970, however, things went astray. Holed up in his Bel Air mansion with coke, PCP, pills, guns, and bodyguards, Sly missed shows, became increasingly paranoid around his bandmates, and with session musicians and a primitive drum machine, made 1971’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On. Both deceptively simple and deceptively complex, it’s the ultimate "death of the 60s" record, an enduring, totally unconventional work with profound influence. After 1973’s Fresh and 1974’s Small Talk, the remains of the original band completely disintegrated. Stone himself slowly faded from relevance, descended further into drugs, and decades later unsuccessfully attempted a comeback.

Of course, anyone who likes Sly Stone enough to buy his book already knows that. We’ve listened to his classic records, we know what they sound like, we’ve heard the myths surrounding them. Hearing it from the man himself seems an exciting proposition, but he’s not a particularly engaging storyteller. There’s generally little insight into his thoughts, feelings, and observations, nor is there much about the creative process. Regarding his late-60s work, he gives play-by-play descriptions of the hits we’ve all heard. He explains Riot as “deeply personal, about the riot that was going on inside each person,” without directly elaborating.

The chapter detailing There’s A Riot Goin’ On is a microcosm of the book’s issues. This is the era when seemingly everyone, especially Sly, was too strung out to properly remember much; thus, there are more stories about Sly & The Family Stone than verifiable facts. One is that the Black Panther Party demanded him to make “militant” music. The book recounts interactions (you could say run-ins) with high ranking Panthers, but neither confirms nor denies the tale. Later in the book, he mentions a tech-savvy fan who visited him and asked about the Maestro Rhythm King drum machine used on Riot. It’s the second of the book’s two references to it, and the first isn’t at all detailed either. Really, what compelled him to use this clunky, preset instrument to groundbreaking effect before any other major artist? Like many such anecdotes surrounding him, we'll probably never know.

The best artist memoirs detail the artist’s life and its effect on the resulting art. Thank You lacks that inter-connectivity; it’s an unfocused work that brings up more questions than provides answers. That said, I appreciate that he didn’t gloss over his addiction, decline, and seclusion. He gives an unvarnished look at those lost decades: crack addiction, reliance on housing and allowances from his managers, getting ripped off by one of those managers, and trying to find work in a world that had moved on. But contrary to earlier in the book, where he recalled his excitement over a positive Rolling Stone review for Dance To The Music, the only time he brings up the public perception of his later years is when expressing disgust over a Spin profile entitled “Sly Stone’s Heart of Darkness.”

After four hospitalizations in 2019, Sly finally got clean from crack cocaine and started this book. Even if it’s not very good, we’re lucky that he wrote it, though one can easily sense what he's lost after 50 years of hard drugs. His wit is still here, but from the perfectionist who once meticulously obsessed over every last detail of his musical arrangements, the man whose work had such clear emotion and captivating excitement, the book's relatively neutral tone and frequent lack of detail is hard to grapple with. There are still a few bits that make it worthwhile enough—what he learned from being uncredited on a song he wrote pre-Family Stone, the fright of being at Terry Melcher's house around Charles Manson, hanging out with Miles Davis, giving Etta James a Cadillac he bought stolen—but Thank You (Fallentinme Be Mice Elf Agin) leaves you wanting more. At least, you want to believe that there's more. Or, perhaps, the story simply isn't as fascinating as the music.

.png)