The Mapleshade Records Story—An Audiophile Jazz Label Reborn

a fascinating insider's account

Mapleshade Records was a haven for jazz-loving audiophiles in the 1990s, a label that combined very good music and excellent sound quality in an era when digital—which, in its early days, usually meant lousy sound—was sweeping through the mainstream industry. Mapleshade’s proprietor-engineer, Pierre Sprey, recorded all his albums on analog tape, with austere minimalism: just two microphones (sometimes three), no processing, not even a mixing board. He stacked bricks on top of his tape recorder and mic preamp, to minimize vibrations. He unplugged the refrigerator while recording, to avoid electrical interference. Yet there was one big frustration: his albums came out on CD only. He would have happily put them out on LP, but there was no market for vinyl back then and nearly no suppliers.

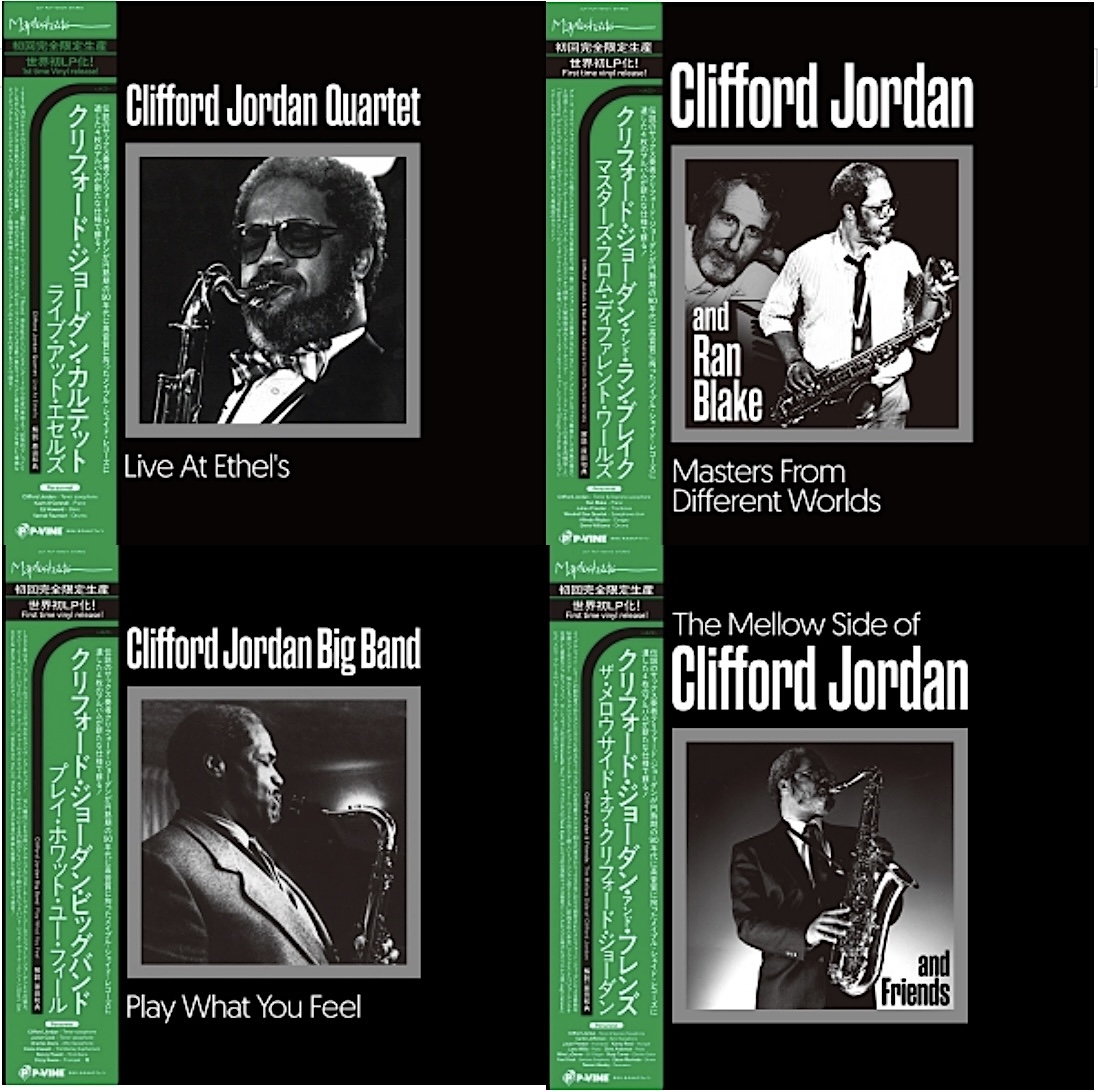

Hence the excitement when I heard last year that the Japanese label P-Vine was putting out four Mapleshade albums on vinyl—specifically, all four of the titles featuring the late tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan. The albums are out now, along with P-Vine’s own remastered CDs, and…well, it’s a mixed story, one of commendations and caviling, requiring some context, both historical and personal.

So Let's Back Up

I met and quickly befriended Pierre Sprey in the early 1980s. I was the military-affairs reporter in the Washington bureau of the Boston Globe. Pierre was the ringleader of a group of defense engineers, analysts, and pilots known as the “military reform movement” or the “fighter mafia” (more about which in a moment). I soon discovered that he was a huge jazz fan. He also knew some local jazz musicians, including the singer-pianist Shirley Horn (before her career-revival on Verve), and would sometimes record concerts (with their permission) on a cheap portable JVC tape machine.

Around this time, a friend of Pierre’s, another defense-world denizen named Bob Dilger (he manufactured the GAU-8 ammunition system for the A-10 attack plane, which Pierre had a role in developing) bought a turntable company—which he renamed Maplenoll—and gave Pierre a unit along with some other bedrock high-end gear. By coincidence, I too had recently got into high-end audio and was reviewing music and equipment for The Absolute Sound (during its heyday of founder Harry Pearson’s editorship). I lent Pierre some issues of the magazine. He was particularly intrigued by HP’s celebration of the early-stereo classical albums on RCA Living Stereo and Mercury Living Presence, especially their use of minimal miking.

Here's where I need to delve a bit into the military reform movement. Back in the late 1960s, Sprey, who was a statistician working in the Pentagon’s office of systems analysis, wrote a paper—based on empirical data—concluding that simple weapons systems were more effective than complex weapons systems. (It was on the basis of that analysis that he became involved in the A-10 and the F-16A jet fighter—and became a critic of complex systems such as the early versions of radar-guided missiles, which were highly vulnerable to smoke, dust, and jamming.) In TAS’ descriptions of RCAs and Mercurys, Sprey saw a possible analog (so to speak) to his own experience with weapons.

Pierre was in his late 40s. (I was in my early 30s.) Long resigned (or booted out of) the Pentagon, he was still doing some statistical consulting for several federal agencies (as well as mentoring journalists like myself). But he had plenty of free time and no need for large sums of money (he was renting a colonial house in the outskirts of Washington), so he started getting more serious about recording music.

He knew a young man named Steven Boyd. The son of John Boyd, a celebrated ex-fighter pilot who was another figure in the military-reform movement and one of Pierre’s best friends, Steven was an amateur recording buff and told Pierre about pressure-zone microphones (PZMs), so Pierre bought some and constructed a wedge-like platform, made of plexiglass, to which he taped the mics at a height and angle simulating a pair of human ears. He also acquired (at an auction, if I recall correctly) a 15-year-old Sony TC-880 tape recorder.

He wasn’t dogmatic in his preference for simplicity. Early on, while preparing to record an audition tape for a D.C.-area jazz sextet, he figured he would need more than two or three mics and tried adding a few more. It turned out the two or three, if well-placed, sounded better. He also borrowed a much-ballyhooed, very expensive microphone preamp that he figured would be better than his cheap model—but it turned out not to be so. He improved the cheap model further by overriding some of its circuitry and replacing the power supply so it ran on batteries. (I took part in a blindfold test comparing the modified cheapie with the expensive model; there was no contest; the cheapie sounded way better.)

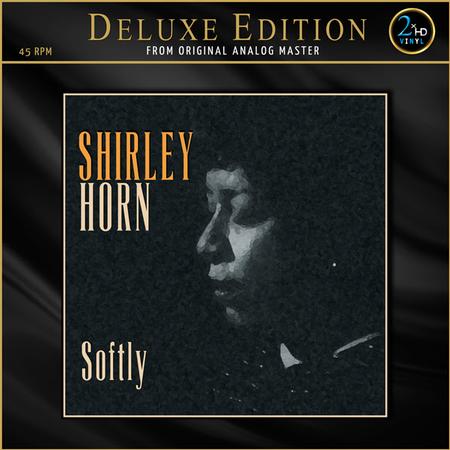

Many years earlier, Pierre had inherited a 1911 Steinway O piano. He didn’t play himself, but some of his jazz friends liked to come over for jam sessions. He had it professionally tuned, re-voiced, and otherwise renovated. Shirley Horn especially liked the set-up and came over to have Pierre engineer an album she’d contracted to do for a label called Audiophile. (The album was called Softly. Pierre didn’t much like the sound, blaming the CD mastering. A Canadian label later put out an LP, from the original analog tapes; I haven’t heard it, but I’m told it sounds great).

The album, mastered by René LaFlamme from the original analog master tapes and cut from the mastered dupe by Bernie Grundman is available as a 2X45rpm set on Fidelio 2xHD Records and is in-stock at Acoustic Sounds _ed.

Over the next few years, he turned the living room of his house—15 by 20 by 10 feet—into a recording studio. To absorb harsh reflections, he covered the walls with eggshell-carton foam. He experimented with where to place his microphone wedge and the piano. There was a French sliding door separating the room from a cavernous entranceway with a steep stairwell. For extra reverb, he would open the doors; for a dryer sound, he would close them. Sometimes, when a singer was part of the band, he would have him or her sing out in the hallway. (He never tried electronic enhancements.) His “control booth” was in an adjoining room, where he would sit on the floor, next to the Sony, and listen through Stax headphones.

In 1987, he formed a company, Mapleshade (which was also the historical name of the house where he lived and now worked). He recorded a series of 10 albums for the Musical Heritage Society. The first was Lonely Woman by the pianist Frank Kimbrough (an acolyte of Shirley Horn’s who at the time was unknown). Another album in the series was Live at Ethell's by Clifford Jordan. (Ethel's was a club in nearby Baltimore; he hauled all of his equipment—the Sony, the mic-wedge, a bunch of bricks that he piled on top of the equipment to minimize vibrations—to the club).

Ed note: It turns out that Ethel's is the correct spelling of the club named after and owned by jazz singe Ethel Ennis. The spelling used on the original CD Live at Ethell's was incorrect and has now been corrected on the new reissues discussed here. But since the original CD was called Live at Ethell's it will be referred to that way when the original CD is referenced. Otherwise the correct name will be used.

Live at Ethell’s was his first of several sessions with Clifford Jordan—and it remains one of the highlights in Mapleshade’s catalogue. (In 1993, Sprey turned the company into an independent label, licensed all of the MHS titles for himself, and started recording many dates in his home-studio for his own label.

Jordan spread the news to many of his fellow jazz musicians in New York, and several of them came down, if at first just to check out this o-fay cat with the funky set-up. They included Hamiet Bluiett, Larry Willis, David Murray, John Hicks, Jack Walrath, and many others.

These were sometimes raucous affairs. The house was very large; Pierre was an excellent cook. Musicians would stay for days at a time, eating great meals, sleeping upstairs. It was also located way out in the country, on an acre or so of land. No neighbors were nearby. Recording sessions could last through the night, into the wee hours, without disturbing anybody.

For the better part of a decade, Mapleshade was very busy—recording aout 125 albums in all, of various genres (mainly but not just jazz), of (inevitably) uneven quality (though more good stuff than might be expected of a small label), and almost all of them sounding very, very good. The late, wonderful jazz engineer, David Baker, who became a friend and informal adviser, once told me, “With some of Pierre’s tapes, it sounds like the band could be right in front of you.”

Then, around the turn of the century, things started to fall apart. Pierre was a brilliant, if eccentric statistician and an inventive engineer, but he was not a businessman, and he was notoriously disorganized in myriad ways. Many musicians in his stable fell away, frustrated by the lack of promotion, even of basic accounting procedures, and, in a few cases, by the rigidity of his recording techniques.

In 2007, a fire broke out in his house. Between the flames and the firefighters’ eager dousing, all of his equipment was damaged or destroyed. The tapes from four recent sessions were ready for mastering, but they never got out of the cannisters. Though he stayed somewhat active in his other spheres, he didn’t record, master, or release another album. He died of a sudden stroke in 2021 at the age of 83.

The company was inherited by Eldon Baldwin, who had been Pierre’s VP since 1993. He’d spent much of that time, putting together the label’s ramshackle business arrangements—and trying to make sense of the tapes, some of which were in unlabeled boxes and all of which were in uncertain condition, especially after the fire. They weren’t burned or doused by the firefighters, but neither had they been kept in temperature-controlled vaults. (When I once jokingly asked Eldon if the tapes had been stored properly, he replied, with a laugh, “How well did you say you knew Pierre?”)

Which brings us up to the recent Japanese CDs and LPs. P-Vine’s proprietor, Yuji Maeda, didn’t set out to reissue Mapleshade albums per se. A few years ago, he’d produced vinyl and digital reissues of some Clifford Jordan albums (notably The Glass Bead Game) and, in the process, struck up a business relationship with Clifford’s widow, Sandy Jordan. (Clifford died of cancer in 1993, at age 61.) Sandy mentioned the four Mapleshade albums that Clifford had recorded. Maeda reached out to Eldon Baldwin.

Now, after luring you in at such great length, I’m going to disappoint you—but hang on, what I’m about to write is not as bad as it sounds, in fact it’s not bad at all, and there’s potentially better news still on the other side.

Here goes: P-Vine’s new vinyl albums of Clifford Jordan’s Mapleshade albums are not mastered from the original analog tapes. Instead, the sources are new digital masters that the Japanese engineers struck from Mapleshade’s CDs (yes, not even from Mapleshade’s digital masters but from copies of the commercially released CDs, though Baldwin tells me that Pierre thought the CDs sounded better than the masters).

The main reason, Baldwin tells me, is that he was reluctant to send original tapes overseas, especially to someone that he didn’t know. Baldwin had also been told, in the years since Pierre died, that the tapes might be in bad shape, owing to the careless storage and possible smoke damage from the fire. But (and here’s the rub) Baldwin doesn’t know. Nobody knows. Nobody has listened to those tapes or checked them out in any serious, professional way. Recall: the original tape recorder is now destroyed. Baldwin recently acquired a replacement recorder, which was recommended by the superb mastering engineer, Christopher Muth, whom he has asked for advice; but, again, no one has followed up.

So, before we get to appraising the relative sonic value of the Mapleshade originals (which are still available) and the P-Vine reissues, as well as the albums’ musical merits, here is my modest plea: Someone who knows what he or she is doing should visit Mapleshade headquarters, take a look at those tapes, take a listen if possible, and then act as a guide, consultant, business partner, or whatever to get the tapes—those that are in good shape, if there are any—to the public.

Baldwin has started to take such steps (hence his conversation with Muth). He would like, to the extent possible, to turn over the entire Mapleshade catalogue to an expert A-to-D mastering engineer, so that, at the very least, the albums can all be available on streaming and downloading platforms. He would like to see many of them released on AAD compact discs. And he would like for the top-caliber titles to come out on 180-gram AAA virgin vinyl. Baldwin is a smart guy; he’s well intentioned; he’s been working at, or running Mapleshade, for more than 30 years; he knows as much as anyone about the catalogue and the physical holdings. But by his own admission, he is not a recording or mastering engineer; he knows little about the record-reissue business. Eldon needs help in spreading the magic. Somebody: help him.

I’ll say this: I listened to several of those tapes many years ago. They sounded fabulous, better than the (excellent-sounding) CDs.

In the meantime, what to make of the P-Vine reissues? I’ve spent a fair number of hours A/B/C’ing (a) the original Mapleshade CDs, (b) the P-Vine CDs, and (c) the P-Vine LPs. In general, the P-Vines (both the digital and the vinyl discs) sound warmer than the originals; they also sound as if overall gain had been boosted (but with no distortion); in some cases, they also reveal more detail. However, on many tracks, the highs seem a bit rolled-off; things like the air Clifford blows through his horn, or the snapping of his fingers, or the sizzle of a trap set’s cymbals sound a bit faded or shrouded.

These differences are minor. If you already have the original albums, I’d say there’s no need to buy the new ones. If you don’t already have them, which should you buy? I’d say it’s a matter of personal taste. Buy the originals if you value those slightly crisper, more shimmering highs; buy the P-Vines if you put a greater premium on midrange warmth and dynamics. Again, the differences are small. With very few exceptions (e.g., the original stereo pressing of Kind of Blue, which I’ll keep for as long as I live), I’m not a sentimentalist when it comes to record-collecting; if I own two editions of an album and one sounds better than the other, I’ll keep it and unload the other. In the case of these four Mapleshade titles, I think I’ll hang on to all three versions of each. (They’re all available from mapleshaderecords.com.)

Anyway, I emailed Yuji Maeda with my observations of the sonic differences between the originals and his reissues, and asked what might account for them. What did his engineers do that might explain any differences at all?

He replied that his engineer created “newly mastered files” for all the albums before pressing his own CDs and LPs. He added: “The original sound quality was already excellent. However, the mastering was done with 1990s equipment and techniques, so we decided to update it for the 2020s. So we have adjusted the levels and resolution to achieve this, as you pointed out.”

I was puzzled. I wrote back, asking how the P-Vine crew “adjusted” the resolution from a 16/44.1 CD? Did they engage in some form of oversampling?

He replied, “I checked with the engineer, and he said that he made minor level adjustments but not equalization adjustments. So the only work done was to adjust the levels.” In an attachment to a follow-on email, the engineer himself detailed what he did:

On Live at Ethel's, all songs were turned up 1.5 dB, limiting with Waves L2 to avoid clipping.

On Masterpieces from Different Worlds (Clifford’s album with pianist Ran Blake and a few other musicians), the sound pressure was raised by 3 dB, with Waves L2, for all songs.

On The Mellow Sound of Clifford Jordan (with lots of friends, recorded over a lot of sessions), levels were raised by 2 to 4 dB, depending on the song. (The tracks were recorded at several different sessions.)

On Play What You Feel (a big band record), three songs were boosted by 1.5 dB, with no limiting.

That explained the boost in gain but not any of the other improvements or shortfalls. I repeated the question, delicately. He replied that his engineer insists the slight gain-boosting was all he did.

Imaginative readers are invited to submit their theories on what might explain the slight sharpening of detail and slight roll-off of highs on these reissues (all of which, I should reiterate, sound very good). Meanwhile, let’s remind ourselves that we are not mere audiophile apes and turn our attention to the music, which (c’mon, wake up!) is what matters most, right?

First, let’s not overlook Clifford Jordan himself—a superb, still-underrated (or perhaps just under-known) tenor saxophonist and composer, blowing in the tradition of Dexter Gordon, Lester Young, and certain strains of Coltrane, but with his own unique traits. A native of Chicago, he dug deep into all the jazz trends of the 1950s on—be-bop, hard bop, the avant-garde of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, and everything in between and since. He led on three dozen albums (including several superb sessions on the Strata-East label, which were collected on a Mosaic boxed set). He played sideman to Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Lee Morgan, Max Roach, among many others.

Live at Ethel's is an impeccable album, one of Jordan’s finest. The first track, a cover of Benny Carter’s “Summer Serenade,” is a gorgeous ballad, with Jordan blowing breezy billows and cascades. On Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” he also sings a verse, with a passion and wit that makes us (or at least me) wish he’d done this more. A cover of Monk’s “Round Midnight” doesn’t pale at all before the dozens (hundreds?) of other covers out there. The album’s three originals—“Blues in Advance,” “Little Boy for So Long,” and “Arapaho”—should have polished his luster as a composer. The finale, “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” shows him fully capable of old-time swinging.

One other thing: His back-up band is top notch—pianist Kevin O’Connell, bassist Ed Howard, and (most notably) drummer Vernel Fournier (best known for backing Ahmad Jamal in the ‘50s). This is a classic, or should be. (Back to sonics for a moment: You hear more of Fournier’s brushwork on the Mapleshade original. A complicating PS: The sound is a bit better still on the Musical Heritage Society CD, and good luck in finding that. One other bonus of the MHS: It begins with Stanley Cowell’s “Cal Massey.” When Pierre reissued the album on Mapleshade, he (wisely) changed the order, so “Summer Serenade” (the album’s strong point) would start it off; however, he (puzzlingly) omitted “Cal Massey.”

Live at Ethel's:

Music

Sound

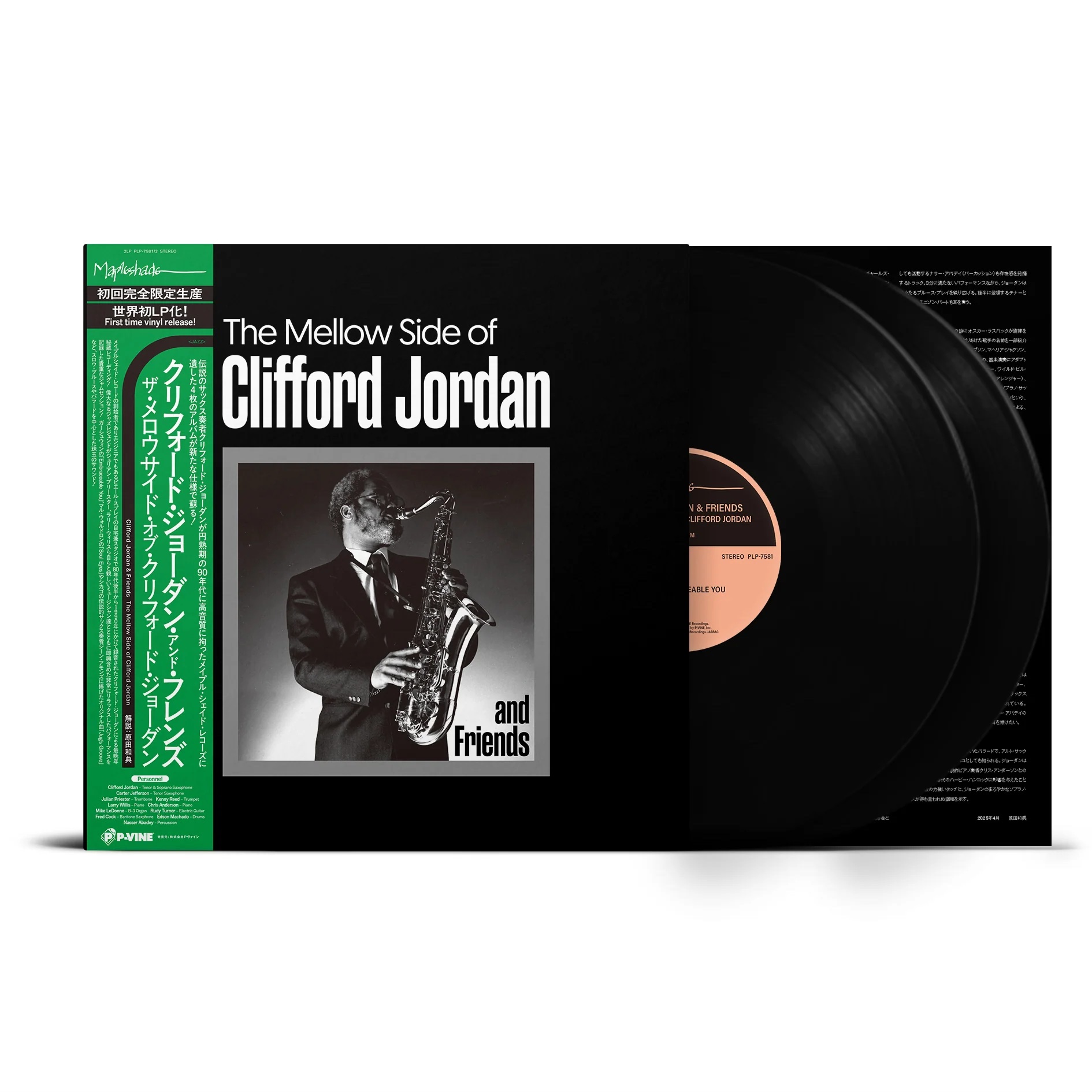

The Mellow Side of Clifford Jordan is a hodgepodge of seven tracks, recorded in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, a tune or two at a time, with a variety of ensembles (sax-piano duos, organ trios, four-horn jams). As Pierre wrote in the liner notes, Clifford would sometimes phone in the middle of the night, say he felt like coming down for a session, show up hours or days later, often with another musician or two in tow, and they’d all play for a while. Pierre assembled the tracks posthumously with an emphasis (as the title suggests) on ballads. It’s a wonderful album for basking or sitting up riveted. “Embraceable You” with an organ trio, “Daydream” with Clifford on soprano sax (backed by Chris Anderson on piano), and a spirited “CJ’s Riff” (with Nasser Abadey tapping and slamming sticks on pots and pans) are among the highlights.

The Mellow Side of Clifford Jordan

Music

Sound

I’m going to skip lightly over Play What You Feel, a big-band album recorded at Condon’s, a now-shuttered club in Greenwich Village. There are some lively tracks, featuring some great musicians (including Junior Cook, Dizzy Reese, and Benny Powell, as well as Clifford up front), but the band was just getting started, the setting was out of Pierre’s comfort zone (and he had little time to prepare). Clifford asked him to come up to record the set for an audition tape, and it succeeded, leading to a contract and one recording session for Milestone records, but Clifford died soon after. It’s a curiosity album, for the most part.

Finally, there’s Masters from Different Worlds, and I’m going to delve a bit deeper on this because I co-produced the session. (I did not draw any income from it, so I don’t think I have a conflict of interest here.) This was originally meant as a Ran Blake album. Ran was (and still is) an eccentric pianist, as wedded to Bartok, Hitchcock, and Pentecostal music as he is to jazz (and several shards of pop). He also has extraordinary ears, which helps make up for his deficit in theory. He’s an acquired taste, but once acquired, it’s a feast. I had known Ran for a few years, having written a profile of him in the Boston Globe, for which I worked as a staff reporter at the time. Initially, this was going to be a duet album with Ran and bassist Charlie Haden (whom I got to know later on, but had only briefly met at this point). Charlie agreed to do it as long as the pair could play for a few days at Blues Alley, the renown DC jazz club. Blues Alley agreed to pay the requested fee ($1,500, if I recall), but then, for reasons I don’t remember, Charlie backed out. Just as well. Pierre brought in Clifford, who brought along trombonist Julian Priester. Steve Williams, at the time Shirley Horn’s ebullient drummer, sat in on a few tracks. So did the local Windmill Saxophone Quartet and congas player Alfredo Mojica.

The session took up a few days between Christmas and New Year’s Day, 1989, and I look back on it as one of my most treasured musical experiences. Clifford and Ran were from different worlds (hence the album’s title, though that wasn’t my idea). They started with a duet, a Ran original, “Vanguard,” which went surprisingly well. Ran had recorded the song several times over the years. This was, as far as I know, the first time it went beyond the basic melody into elongated improvisations.

Then came “Something to Live For.” They went through the head a few times, Clifford growing a bit frustrated at the key changes Ran was swirling through (as was his wont). A second before the reels started, Clifford said, “How about if you take the melody and I’ll accompany.” Ran opened with an uptempo intro that raised my eyebrows, then moved into a single-note melody line while Clifford barreled in with eighth- and sixteenth-note harmonic constructions. A minute or so into the tune, as Ran’s angular accents and Clifford’s fluent flurries seemed just about to spin out of control, Ran pounded out a series of block chords, Clifford wound down his passage, they met on an identical note in a very bluesy resolution of what had been a few bars of wincing tension, then they set off on a spontaneous excursion of variations of Strayhorn’s tunes—as a dark waltz, a romantic ballad, a tango, an avant howler—trading off parts effortlessly, interlockingly. Rarely have I heard, before or since, two players listening so carefully to each other’s cues, while heading out in so many directions. It was all done in one take, and I remember Pierre and me exchanging glances, several times, with our eyes very wide open.

If nothing else had come of the weekend, the album would be worthwhile, I think, but there was much more. Duos, trios, larger ensembles, a vocalist on a couple of tracks, and a wild variety of songs—“A Touch of Evil” (inspired by the Orson Welles film), “Laura” (from Otto Preminger’s film), “Short Life of Barbara Monk” (a tribute to Thelonious’ daughter, whom Ran once babysat and who died at a young age), “Doug’s Prelude” (Clifford’s balladic tribute to Doug Watkins), a crazy-quilt cover of Bacharach’s “Wives and Lovers,” a piano-drums duet of Ellington’s “Mood Indigo,” and a piano solo of John Lennon’s “Julia.”

At one point, Ran laid down a whole reel of piano solos, without interruption, as the sun went down and the room turned dark, except for a candle illuminating a small framed photo of Billie Holiday that he’d brought down from Boston for inspiration. The reel should be in Mapleshade’s vaults somewhere. There should also be a reel of piano-drum duets with Steve Williams. We decided only to use one song from each for the final album, to make room for more Clifford and some larger ensembles, but (attention, Eldon!) they might be worth a listen.

This is the one P-Vine reissue where the LP sounds more than a little bit better than the CD. I don’t know why—and I would keep in mind my earlier remark, which holds here as well, about the relative strengths and weaknesses of Mapleshades vs. P-Vines in general.

Music

Sound

Mapleshade Records did not exist as a label just yet. We tried to shop the tapes around to a few labels. I remember sending a cassette copy of the finished version to Michael Cuscuna at Blue Note. I called him a couple weeks later, asked if he’d listened to it. He replied, “Yeah! Loved it!” I asked if Blue Note might be interested in releasing it. He laughed, rather loudly, and said, “Noooo.” Ran has always been a tough sale. Still, I think this album is a gem, though yeah, I might be biased. (At this writing, Ran is about to turn 90 and is still churning out remarkably imaginative music.)

The Mapleshade catalogue is well worth exploring, despite its sorry ending, especially for audiophiles; the sound quality is, for the most part, first-rate by any standards. Let’s hope that P-Vine’s reissues are just the beginning of a rebirth.

A Visit to Pierre Sprey's Home and Headquarters:

Clifford Jordan Live in Norway:

.png)