The Wonderful World of Decca Phase 4 Stereo: BOND and BEYOND with Roland Shaw and his Orchestra - PART 1

Head back to the 1960s for these cool slabs of vinyl that caught the music of the secret agent craze to perfection

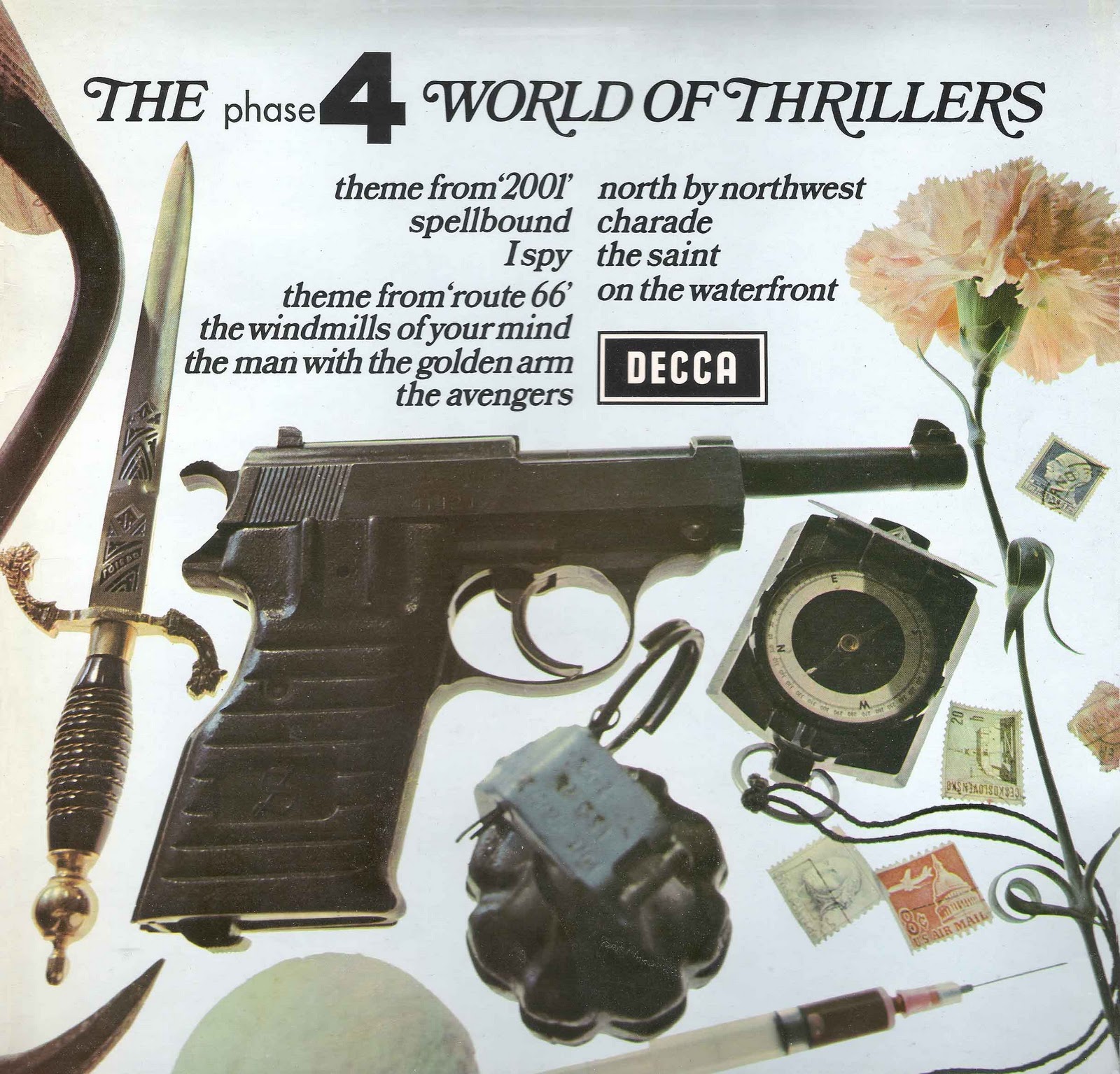

Anyone who collects records has the story of a "Eureka!" moment. A moment when they happened upon a new record of unfamiliar music that, for whatever reason, was a revelation, and subsequently became a firm favorite, a cornerstone of their collection. I’ve had a number of such moments, but one of the first happened when I was around 12. Leafing through the record bins I happened upon a collection titled "The Phase 4 World of Thrillers". The cover was the first thing to catch my attention. It featured all the accoutrements of the gentleman spy and world adventurer, guaranteed to pique the interest of a kid who was already devouring James Bond’s adventures on the page and screen at every possible opportunity.

But the title intrigued too. What was this “Phase 4” thing all about? Quite a few “Phase 4” records littered the bins, both in the Classical and Easy Listening sections. Scanning the track listing of this record in my hands, "The Phase 4 World of Thrillers" revealed an eclectic range of music drawn from movies and TV shows. It was on the Decca label, and the price was right – 99 pence – (ie. almost one pound sterling) – so I plonked down my lawn-mowing pocket-money and hurried home to listen.

But the title intrigued too. What was this “Phase 4” thing all about? Quite a few “Phase 4” records littered the bins, both in the Classical and Easy Listening sections. Scanning the track listing of this record in my hands, "The Phase 4 World of Thrillers" revealed an eclectic range of music drawn from movies and TV shows. It was on the Decca label, and the price was right – 99 pence – (ie. almost one pound sterling) – so I plonked down my lawn-mowing pocket-money and hurried home to listen.

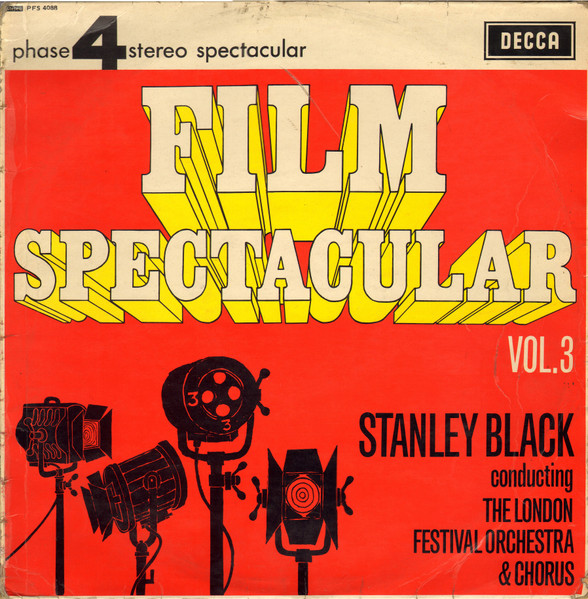

Immediately I knew this was a different kind of record. The sound was Technicolor rich and vivid, taking full advantage of what were then new multitrack recording techniques to exploit and fill the stereo field with arresting sounds. The arrangements were likewise larger-than-life and eclectic in the manner of Easy Listening records of that vintage. The tracks featured an array of Decca’s top so-called “light music” performers and session players. Divvying up the main duties were two label stalwarts: Stanley Black and Roland Shaw, supplemented by Frank Chacksfield and his Orchestra and the stereo novelty act of Ronnie Aldrich and his Two Pianos.

All the music was compelling, from Leonard Bernstein’s jazz-inflected On the Waterfront to Miklos Rozsa’s lurid Hollywood fantasmagoria, Spellbound, but the tracks that most caught my schoolboy imagination were those by Roland Shaw, of themes from spy movies.

The music flew out of the grooves, sexy and sassy, with gigantic drums and bass guitar, tight brass licks, and kinetic strings. The track that really blew my ears back was for the American TV show, I Spy.

Just listen to the way those opening mega drums propel us forward. (The drumming on all Phase 4 records was fantastic, tight and in your face when it needed to be – was it the same guy, and if so, who was he?). The brass kicks it up a notch, and then that propulsive, MASSIVE bass guitar anchors the groove while the strings punch out the theme like they are on a combination of speed and caviar. A blistering sax solo unfurls against rhythm guitar, then it's back to those strings and fat horns punching up the 60s glam. On a good stereo, the vinyl practically catches fire, filling the room with three-dimensional sound.

And so began my collecting obsession with Decca Phase 4 Stereo. Every time I go to a used record store I head over to the Easy Listening section to see what I can find. There are a slew of desirable records to be found by the likes of Frank Chacksfield, Ronnie Aldrich, even Mantovani.

Phase 4 also sported a generous catalogue of classical titles, featuring such luminaries as Leopold Stokowski - the original Technicolor re-orchestrator - and Bernard Herrmann. Herrmann recorded not only unusual classical programs (Ives’s 2nd Symphony anyone?), but also a bunch of his own film music on a series of albums that have become audiophile classics. In-house favorite Stanley Black embarked on his own series of film music albums. In fact, before the advent of the RCA Classic Film Score series of film music albums in the 1970s, Phase 4 was pretty much the only film music game in town (beyond original soundtrack records), sporting first-class cover versions of both familiar and less familiar scores.

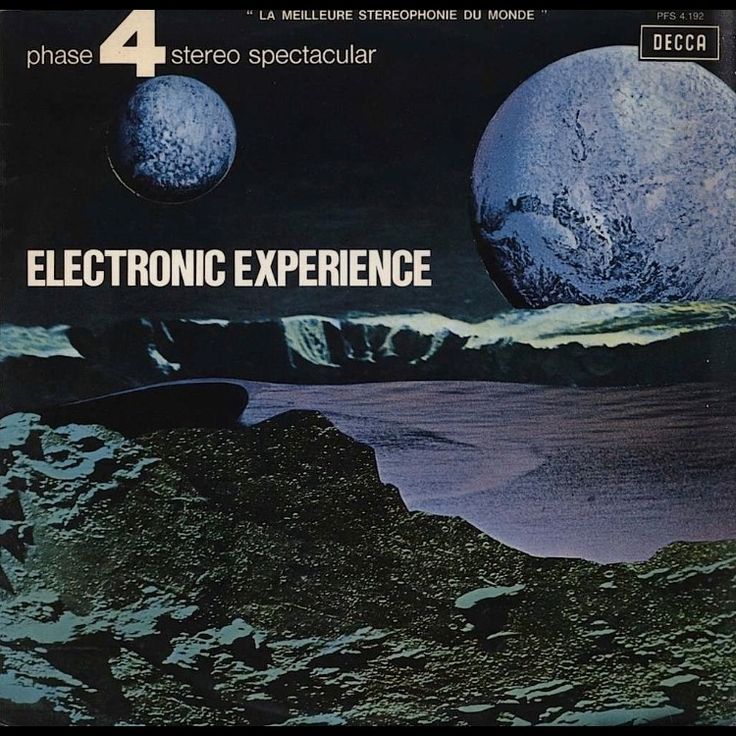

Hell, Phase 4 even got into the Moog synthesizer craze that took over the easy listening market in the wake of the massive success of Walter (later Wendy) Carlos’s Switched-On-Bach.

But I thought I’d launch what will be a series of occasional articles covering all corners of the Phase 4 catalogue with a survey of those marvelous records by Roland Shaw and his Orchestra, covering mainly the James Bond films, with occasional forays into other spy film and TV scores of the period. Quite apart from the vivid sound, these records contain the only arrangements and recordings of John Barry’s and other similar composers’ music that rival (and sometimes exceed) the composers’ own (which were issued both on original soundtrack albums and later compendiums of new recordings on various labels; for example, Barry on CBS, Mancini on RCA).

But I thought I’d launch what will be a series of occasional articles covering all corners of the Phase 4 catalogue with a survey of those marvelous records by Roland Shaw and his Orchestra, covering mainly the James Bond films, with occasional forays into other spy film and TV scores of the period. Quite apart from the vivid sound, these records contain the only arrangements and recordings of John Barry’s and other similar composers’ music that rival (and sometimes exceed) the composers’ own (which were issued both on original soundtrack albums and later compendiums of new recordings on various labels; for example, Barry on CBS, Mancini on RCA).

To paraphrase the words of the immortal Ms. Bette Davis in All About Eve: “Fasten your seatbelts - it’s going to be a bumpy ride!”

The Origins of Decca Phase 4 Stereo

Cast your mind back to the fecund record industry days of the 1960s. With the advent of the long-playing, 33rpm LPs and stereo sound, there was an explosion of titles released to suit every taste. Record labels quickly realized that the new stereo technology was a draw in and of itself, and so embarked on a whole series of albums designed to show off the “ping-pong” effects made possible by having two loudspeakers reproducing different instruments and sounds sitting in the listener’s living room.

Cast your mind back to the fecund record industry days of the 1960s. With the advent of the long-playing, 33rpm LPs and stereo sound, there was an explosion of titles released to suit every taste. Record labels quickly realized that the new stereo technology was a draw in and of itself, and so embarked on a whole series of albums designed to show off the “ping-pong” effects made possible by having two loudspeakers reproducing different instruments and sounds sitting in the listener’s living room.

Now you have to remember that in these early days of stereo many artists, both classical and popular, continued to believe that mono was the real deal, stereo just a gimmick, a passing fad. The most famous example of this is The Beatles, who only supervised the mono mixes of their records up to Abbey Road, leaving the mixing of the stereo versions to the Abbey Road engineers.

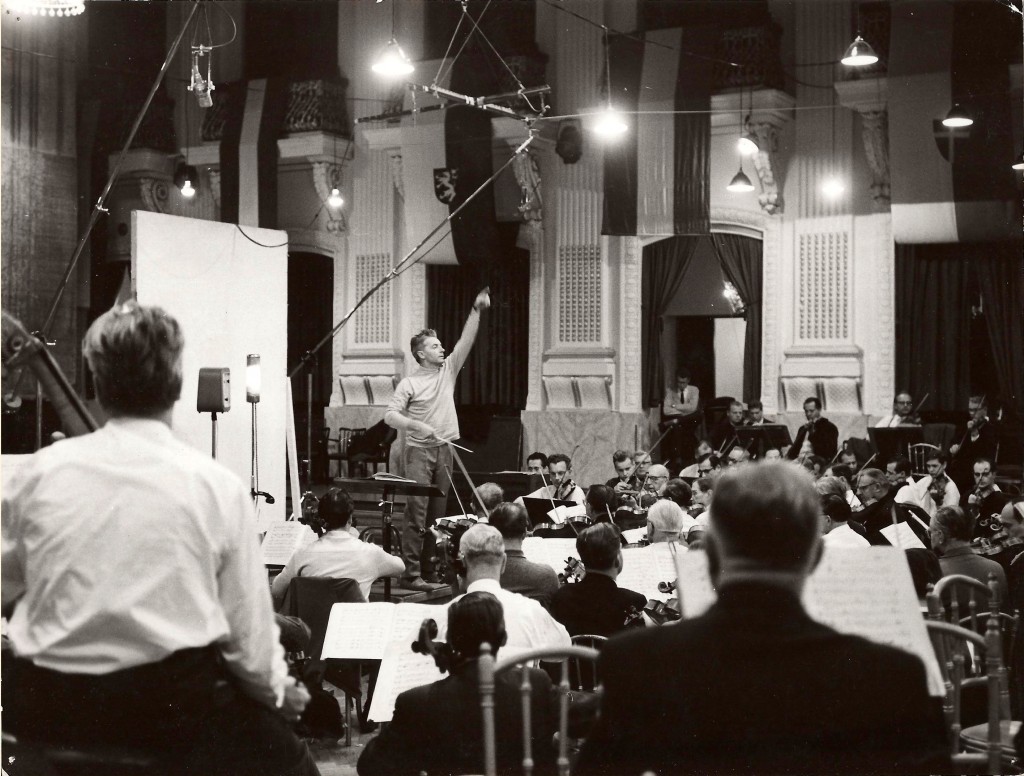

I did not know it back when my 12-year-old self bought that “Phase 4 World of Thrillers” album, but Phase 4 Stereo was something more than a marketing gimmick. Decca had long enjoyed the highest reputation amongst audiophiles and record collectors for the quality of its classical recordings, achieved by the famous “Decca tree” of microphones. This was a simple arrangement of three microphones suspended above the conductor's head, whose aim was to "hear" the orchestra like the conductor did, in natural proportions from this optimal position. (A few supplemental microphones were carefully placed at strategic points within the orchestra to add detail to the primary sound image). It was a minimalist approach to recording which echoed that of the similarly esteemed American audiophile labels, Mercury ("Living Presence") and RCA ("Living Stereo").

Herbert von Karajan recording with the Vienna Philharmonic in the Sofiensaal. You can see the "tree" above his head.

Herbert von Karajan recording with the Vienna Philharmonic in the Sofiensaal. You can see the "tree" above his head.

In many ways the apogee of this approach to recording had been the historic release of Wagner’s monumental Ring cycle of operas under Georg Solti, produced by the legendary John Culshaw between 1958 and 1965, complete with sound effects and singers wandering around the imaginary aural stage created by the stereo speakers, just like in a radio drama.

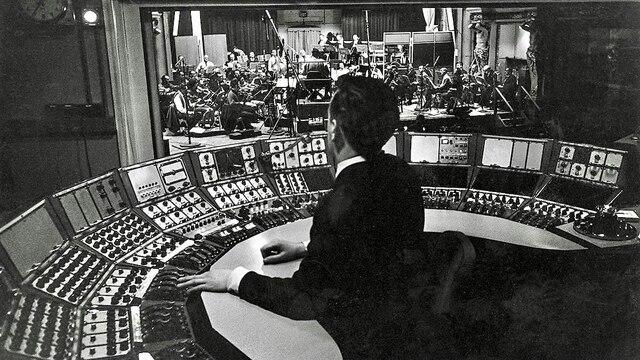

With the advent of first multi-track mixing consoles, and then multi-track tape recorders in the 60s, more microphones crept into recording sessions, and the increasing tendency was for the producer and engineers to fine-tune the balance of the orchestra long after the session, rather than do so only as the recording took place. The result, over succeeding decades, was a sound which, while more refined, with each instrument carefully placed and balanced against every other instrument, lost some of its energy and sense of “liveness”.

What was different about the Phase 4 recordings was that, even though they were multi-miked and artificially balanced, deliberately incorporating the idea of "stereo cool" into their marketing, they retained that sense of “liveness”.

At the time when the Phase 4 Stereo division was created by Decca/London in 1961, multi-track recording techniques barely existed, because tape recorders were restricted to 2, then 4 tracks. On the rock side of the business, to create multi-layered recordings, a technique of recording, then bouncing down (ie. combining) tracks into sub mixes using multiple machines was developed by a number of record companies and producers, most famously spearheaded by the Beatles.

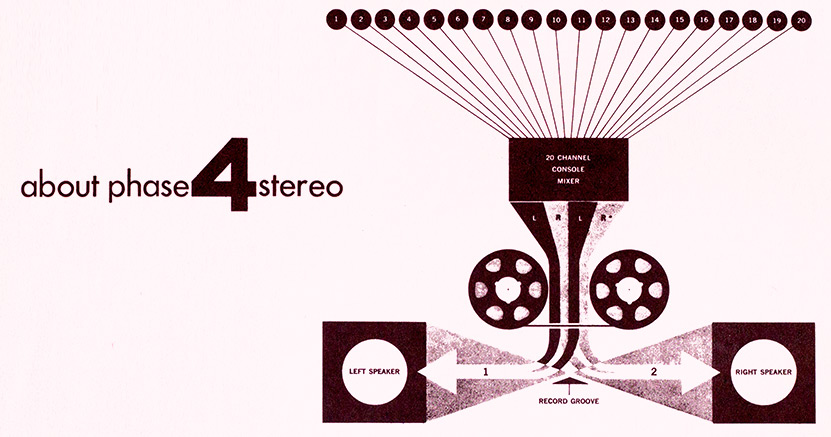

The innovation at Phase 4 was to build a 10-channel mixer (later expanded to 20-channels), which enabled the engineers to spotlight particular instruments or groups of instruments “live”, during the sessions. The music arrangers also built the concept of “pre-mixing” into their arrangements, highlighting certain instruments or effects as the track went along. All of this meant you had the illusion of multi-tracking without the drawbacks of increased tape hiss each time you went down a generation - the principal drawback of creating endless sub-mixes from bouncing down tracks.

Combining this purist recording approach with Decca’s well-established reputation for excellent sonics meant that the Phase 4 releases immediately established a benchmark for vivid, engaging light entertainment records.

An integral part of achieving this level of quality lay in the deep roster of arranging and playing talent that was everywhere in England - and especially London - during the 1960s, all of which Decca made full use of. The reason for the presence of these resources? The existence of the state-funded BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), which via its numerous local and national radio stations, had need of huge amounts of musical material that could fill the broadcast day. For example, Radio 2 - the light music program - had live broadcasts going out each week, the most famous of which was “Friday Night is Music Night”. This program started in 1953, and continued through to 2023. I attended a few broadcasts in the 80s because I had friends performing.

An integral part of achieving this level of quality lay in the deep roster of arranging and playing talent that was everywhere in England - and especially London - during the 1960s, all of which Decca made full use of. The reason for the presence of these resources? The existence of the state-funded BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), which via its numerous local and national radio stations, had need of huge amounts of musical material that could fill the broadcast day. For example, Radio 2 - the light music program - had live broadcasts going out each week, the most famous of which was “Friday Night is Music Night”. This program started in 1953, and continued through to 2023. I attended a few broadcasts in the 80s because I had friends performing.

"Friday Night is Music Night" - The View from the Recording Booth, 1965, at the Camden Theater

"Friday Night is Music Night" - The View from the Recording Booth, 1965, at the Camden Theater

The show was broadcast live from a former vaudeville theatre in London. It was packed. With a full band and choir on stage, plus soloists and a presenter, the show ran 2 hours, and was a feast of the very best in light music arranging and performing.

London in the 1960s was also a major hub for all manner of rock and pop recording, plus so-called library music that was licensed to numerous film, TV and commercial companies looking for background music. This was the world in which future Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page and other future rock luminaries made a very good living as freelance studio musicians when they were starting out.

This is the thing that first strikes you when you put on a Phase 4 record, no matter who the artist is, or the style of music: the high level of musicianship on display in the arranging and performances, all captured in excellent sound matched only by the best from RCA and Mercury in the US, and later some of the EMI releases in England.

What, you may ask, did “Phase 4” refer to? Liner notes from the earlier releases attempted to explain. Phase 1 was the development of stereo itself. Phase 2 was the use of the two channels to create spatial effects, like having sounds or music travel across the sound field. Phase 3 was the process by which engineers could place or move sounds, voices or music in different positions in the stereo sound field (by using panning knobs on their mixers). Phase 4 was described by the label thus:

What, you may ask, did “Phase 4” refer to? Liner notes from the earlier releases attempted to explain. Phase 1 was the development of stereo itself. Phase 2 was the use of the two channels to create spatial effects, like having sounds or music travel across the sound field. Phase 3 was the process by which engineers could place or move sounds, voices or music in different positions in the stereo sound field (by using panning knobs on their mixers). Phase 4 was described by the label thus:

“New Scoring Concepts Incorporating True Musical Use of Separation and Movement. In this phase, arrangers and orchestrators re-score the music to place the instruments where they are musically most desired at any particular moment and make use of direction and movement to punctuate the musicality of sounds. The effect is more sound -- more interest -- more entertainment -- more participation -- more listening pleasure: PHASE 4 STEREO is not background music."

For sure. Drop the needle on any Phase 4 record and you will hear a palpable sense of excitement pouring out of the grooves. These records are FUN to listen to.

The instrumental colors are rich and vibrant, at times almost over-ripe. The recordings retained many of the qualities that had made earlier Decca records audiophile favorites, while adding the extra spice of the Easy Listening palette of unusual instrumental combinations. The arrangements reveled in artificial stereo effects, exotic orchestrations and even specially created sound effects, and the result was records which were spectacular showcases for the musicians, the music – and the listener's stereo system.

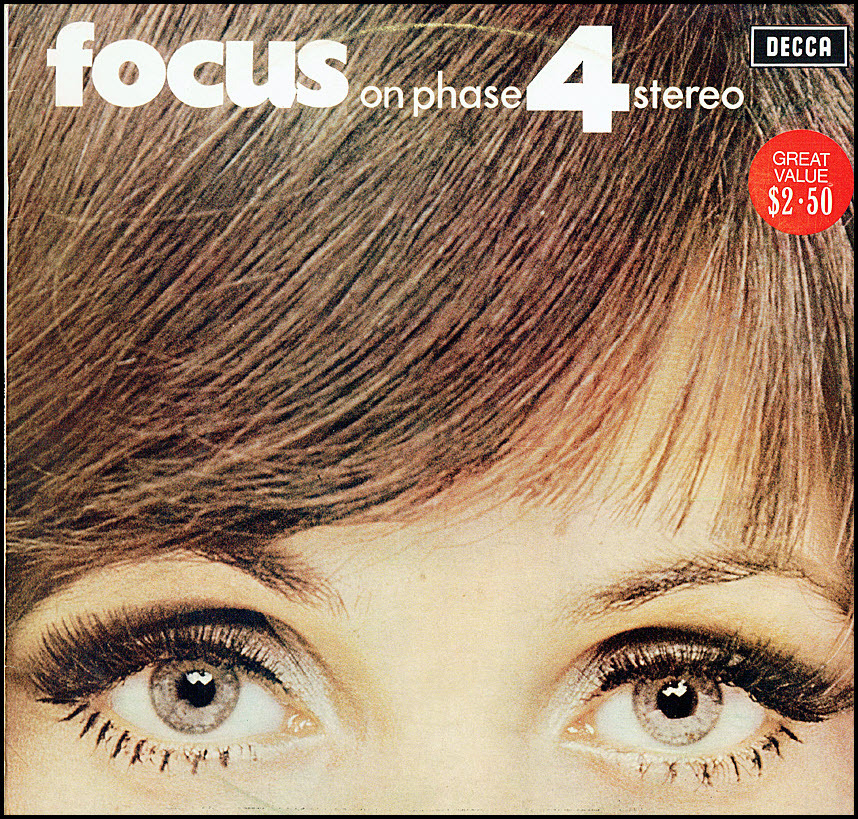

A 1965 Italian Pressing

A 1965 Italian Pressing

The sound was matched by gloriously eye-catching photography and cover design graphics. Everything - from the visual representation of the technological process to the cover art - popped! This was 1960s Carnaby Street and Madison Avenue distilled onto a record sleeve. Even the centre labels of the records themselves sported a distinctive red and white design, miles away from the more staid blue and black labels of Decca’s classical and rock releases. (Some early Phase 4s still sported that dark blue label).

Now, the advantage of acquiring the London (ie. US) versions of these records over the regular British Decca releases was that they often came in elaborate gatefolds, with extra photos and sleeve notes (especially welcome in Stanley Black’s series of film music records). As to the sound, nearly all the American London Phase 4 records were pressed in the UK, like their Decca counterparts. I will not wade into the ongoing debate as to whether there are any sonic differences to be heard between the London and Decca Phase 4 LPs; I have yet to hear any significant differences myself, but I welcome your opinions in the Comments section at the end of this article. Bottom line: when buying the London Phase 4s, just be sure they are made in the UK, which will be printed on the record label. (If that designation is missing, do not waste your money - it’s a US or other country of origin pressing).

Now, the advantage of acquiring the London (ie. US) versions of these records over the regular British Decca releases was that they often came in elaborate gatefolds, with extra photos and sleeve notes (especially welcome in Stanley Black’s series of film music records). As to the sound, nearly all the American London Phase 4 records were pressed in the UK, like their Decca counterparts. I will not wade into the ongoing debate as to whether there are any sonic differences to be heard between the London and Decca Phase 4 LPs; I have yet to hear any significant differences myself, but I welcome your opinions in the Comments section at the end of this article. Bottom line: when buying the London Phase 4s, just be sure they are made in the UK, which will be printed on the record label. (If that designation is missing, do not waste your money - it’s a US or other country of origin pressing).

Another point: earlier pressings will have been mastered using tubes in the mastering chain, just like their classical and rock counterparts. Therefore with early, pre-late 60s releases, you will hear a subtle difference between earlier pressings and the later ones, where tubes are no longer in the circuit. For some, this will be a negligible difference; for others, it will always be worth going for that earlier pressing. (Earlier pressings have a slightly different center label, as you can see above).

In later articles I will talk about some of the other Phase 4 records which occupy pride of place in my collection. These include numerous “Easy Listening” records, and classical recordings that run the range from forgettable to genuinely interesting. Some of the most important releases in the Phase 4 catalogue belong to the great American film composer Bernard Herrmann, whose seminal re-recordings of his (and others’) film music paved the way for the RCA Classic Film Score Series, and played an essential role in establishing the legitimacy of film music recordings as standalone LPs away from the films they were scored for.

Along with Herrmann’s pioneering film music releases, the Phase 4 catalogue also boasts the aforementioned Stanley Black’s series of film music albums which were huge sellers, and covered an incredible range and style of film music: everything from Chaplin’s music for his own films to the Americana of the original Stagecoach score; from William Walton’s indelible music for Laurence Olivier’s Henry V to James Bond, Mary Poppins and Zorba the Greek.

Along with Herrmann’s pioneering film music releases, the Phase 4 catalogue also boasts the aforementioned Stanley Black’s series of film music albums which were huge sellers, and covered an incredible range and style of film music: everything from Chaplin’s music for his own films to the Americana of the original Stagecoach score; from William Walton’s indelible music for Laurence Olivier’s Henry V to James Bond, Mary Poppins and Zorba the Greek.

AND - speaking of James Bond. One of Stanley Black’s main arrangers was Roland Shaw, and it’s no accident that Shaw ended up with his own series of Phase 4 records. His formidable skills as an arranger were widely known, and his handful of records made as leader for the label are amongst the most prized by audiophiles and secret agent music junkies.

AND - speaking of James Bond. One of Stanley Black’s main arrangers was Roland Shaw, and it’s no accident that Shaw ended up with his own series of Phase 4 records. His formidable skills as an arranger were widely known, and his handful of records made as leader for the label are amongst the most prized by audiophiles and secret agent music junkies.

Time to press “PLAY” on the Roland Shaw entries in the Phase 4 catalogue.

Roland Shaw and his Orchestra in Action

If you want to get an immediate sense of how Roland Shaw spiced up what were already pretty great originals, listen no further than his arrangement and performance of Burt Bacharach's theme for the "alternative" Bond romp, Casino Royale. The original was recorded with Herb Alpert channelling his Tijuana Brass idiom to dazzling effect, and that whole soundtrack album is a long-established audiophile classic (with the main theme song being one of my personal Desert Island picks). But just listen to how Shaw channels the energy of the original, expands the brass section (hard left and hard right), adds jangling rhythm guitar and (again) that fabulous drumming, complete with the addition of screaming girls. With all due deference to the brilliant original, this is all just too much fun.

Roland Shaw

Roland Shaw

As a youngster, Shaw had attended Trinity College of Music in London. Starting out as a drummer he migrated to piano after hearing the great Teddy Wilson. During World War II he served with the RAF and led the RAF No.1 Band of the Middle East Forces. He quickly gravitated towards arranging.

Will it surprise you to learn that Roland Shaw’s greatest passion - alongside music - was motor cars, of which he owned several exotic examples over the years? These ranged from a Rolls-Royce to a Bentley and a beautiful classic red Ferrari. He competed in club meetings at Silverstone, Goodwood and Brands Hatch, where he often acted as a race marshal. In fact, it was while parking his Rolls (purchased with a royalty check from “Tutti” Camerata, who helped to found Disneyland Records, and made several albums of his own for Phase 4) near Shaw’s home in Barnes that he got his break with Decca Records. Shaw was approached by an admirer of the vehicle, who turned out to be Frank Lee, head of A&R at the label. He went on to become one of Decca's principal house arrangers, working for Vera Lynn, Mantovani, Ted Heath, and, as already mentioned, Stanley Black. He also worked on several films as an original composer, including The Great Waltz, Summer Holiday, and Song of Norway.

(Sidebar: Barnes, a sleepy almost-suburb of London bordering on the southern bank of the Thames, was also home to the legendary Olympic Studios, where I attended several memorable film scoring sessions in the early 80s and heard stories about working with Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, the Stones etc. from legendary in-house engineer, Keith Grant).

There was so much work at Decca, Shaw was able to work with the same band of top studio musicians. In his sleeve notes for the double CD release on Poker Records of Shaw's Phase 4 Bond recordings, Fred Dellar quotes him as saying: "I gave these players so many sessions that they were able to give Phase 4 and London Records priority. And as Duke Ellington once said when asked how he managed to keep so many fine players together - I gave them money!"

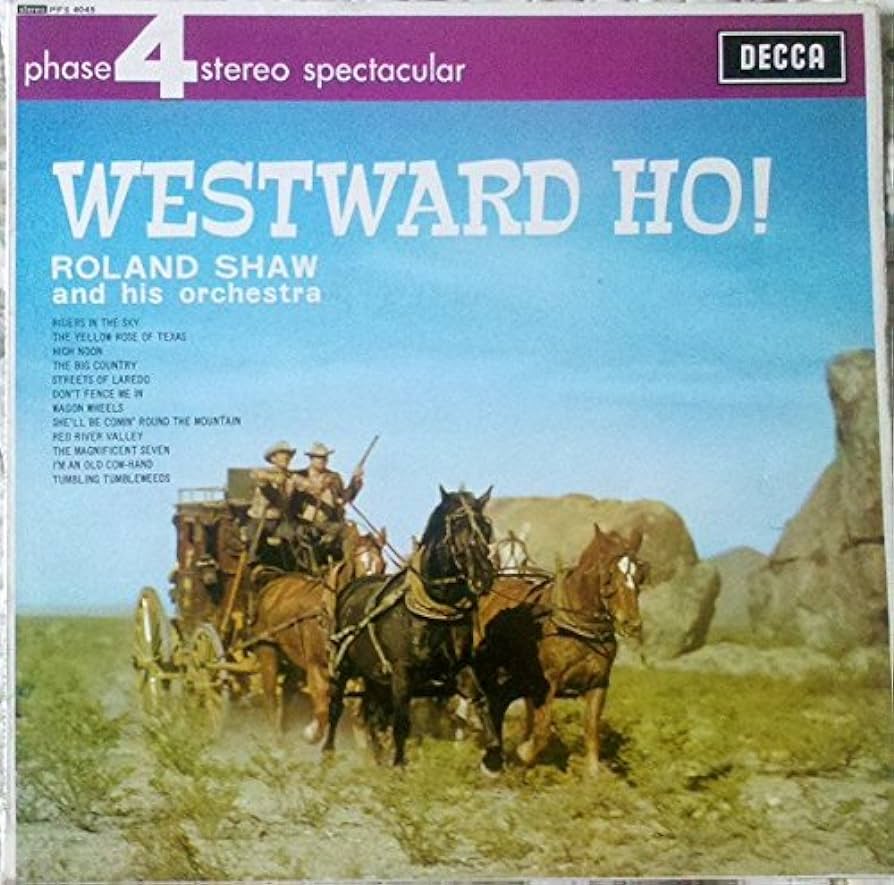

Prior to his James Bond/Secret Agent albums, Roland Shaw’s two outings as headlining band leader on Phase 4 were Mexico (1963) and Westward Ho! (1964), both catering to the record buying public’s endless appetite for light music tinged with foreign exotica.

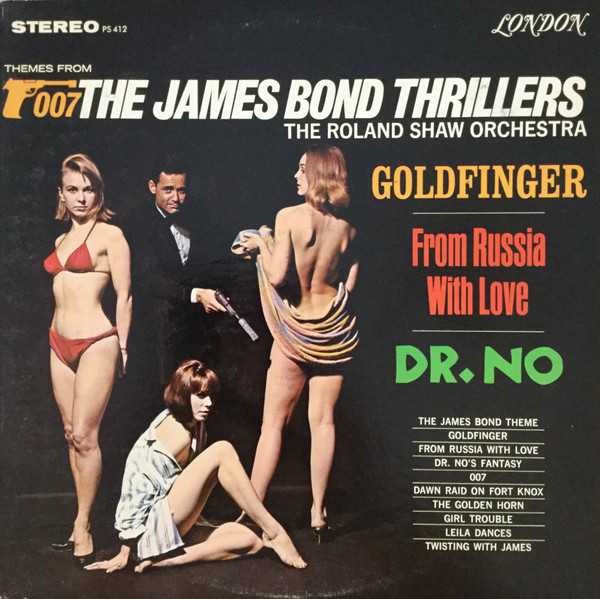

But it was the London Records Phase 4 release of Shaw's first spy genre album, Themes from the James Bond Thrillers, also in 1964, timed to coincide with Goldfinger, that really established his name upfront and center. It was a massive hit, spawning a number of sequels.

But it was the London Records Phase 4 release of Shaw's first spy genre album, Themes from the James Bond Thrillers, also in 1964, timed to coincide with Goldfinger, that really established his name upfront and center. It was a massive hit, spawning a number of sequels.

(A quick note here. The Roland Shaw Bond and Secret Agent recordings exist in a number of configurations and combinations on both London and Decca, some of which recycle older tracks with new additions, usually timed to come out with subsequent Bond films. If you want to get absolutely everything, some duplication is going to occur. But the essentials to cover your bases will be covered below).

(A quick note here. The Roland Shaw Bond and Secret Agent recordings exist in a number of configurations and combinations on both London and Decca, some of which recycle older tracks with new additions, usually timed to come out with subsequent Bond films. If you want to get absolutely everything, some duplication is going to occur. But the essentials to cover your bases will be covered below).

Today it’s impossible to imagine the Bond films without the template musical sound created and established by John Barry. But people forget that the first film, Dr. No (1962), was scored by Monty Norman in a somewhat different style, with Barry only doing an arrangement of an obscure Norman composition to create the iconic James Bond Theme (the subject of much later litigation between Barry and Norman). Norman’s score leans heavily on the influence of the colorful Jamaican sound, and actually my 1978 reissue LP of the original soundtrack score sounds terrific. But this is a long way from Barry’s sophisticated Bond stylings.

Shaw's arrangements fill out the minimally orchestrated Monty Norman originals to great effect. In this track, Underneath the Mango Tree, the addition of rippling flute and harp, plus quivering strings, creates a vivid sense of travelogue exotica.

However, it was John Barry's iconic arrangement of the James Bond Theme, and his scores for From Russia with Love and beyond, which defined the "Spy Sound" of the Swinging Sixties soundtrack. Barry seamlessly blended his jazz and pop background with lush romantic strings and heavy Wagnerian brass chords (interspersed with fabulous, soaring breaks that wailed over the propulsive drums and bass) to create a sound that defined the cool of Bond every bit as much as did the beautiful girls, designer clothes, exotic locations and futuristic gadgets. The later addition of the Moog synthesizer to the score for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) added another contemporary flavor, as did the drum machine which re-invigorated Barry’s final Bond outing The Living Daylights (1987), one of the composer’s best Bond scores, and notable also for the best Bond song nobody knows, Where has Everybody Gone?, a collaboration with Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders.

However, it must be noted, that it was composers like Alex North (A Streetcar Named Desire 1951), Fred Steiner (Perry Mason 1957), Elmer Bernstein (The Man with the Golden Arm 1955), and Henry Mancini in his scores for films like Touch of Evil (1958) and the TV show Peter Gunn (1958, with a popular soundtrack album issued on RCA in 1959), who first established that jazz flavour in mainstream popular entertainments that was so important an element of the Bond and the 60s spy sound. Barry built upon their example, first in his late 50s and early 60s records for EMI, and later in the Bond scores, also bringing the nascent rock sound into the mix.

John Barry himself epitomized Swinging London just as much as the spy whose musical identity he helped forge on the big screen. He was quite the man about town. Barry is seen here with his wife at the time, actress and singer Jane Birkin.

As the popularity of the Bond films soared, record labels were jumping over themselves to create knock-off compilations of Bond and other spy music, using various Easy Listening arrangers and scratch bands. The results were frequently lacklustre, but every so often these cover versions struck gold. Such was the case with Roland Shaw's series of albums for Decca Phase 4.

As the popularity of the Bond films soared, record labels were jumping over themselves to create knock-off compilations of Bond and other spy music, using various Easy Listening arrangers and scratch bands. The results were frequently lacklustre, but every so often these cover versions struck gold. Such was the case with Roland Shaw's series of albums for Decca Phase 4.

(For me the only serious competitor to Roland Shaw’s albums in terms of achieving consistent quality in cover versions of this music were recorded by American guitarist Billy Strange, a member of the famed studio outfit The Wrecking Crew. These albums on GNP Crescendo are well worth seeking out; Strange’s version of Bacharach’s Casino Royale is a particular favorite).

Don't put that Martini anywhere! The musical action continues in PART 2.....

.png)