Marquee Moon....Tom Verlaine and Television's "Not Punk Rock" Masterpiece

A Personal History Of Punk Rock

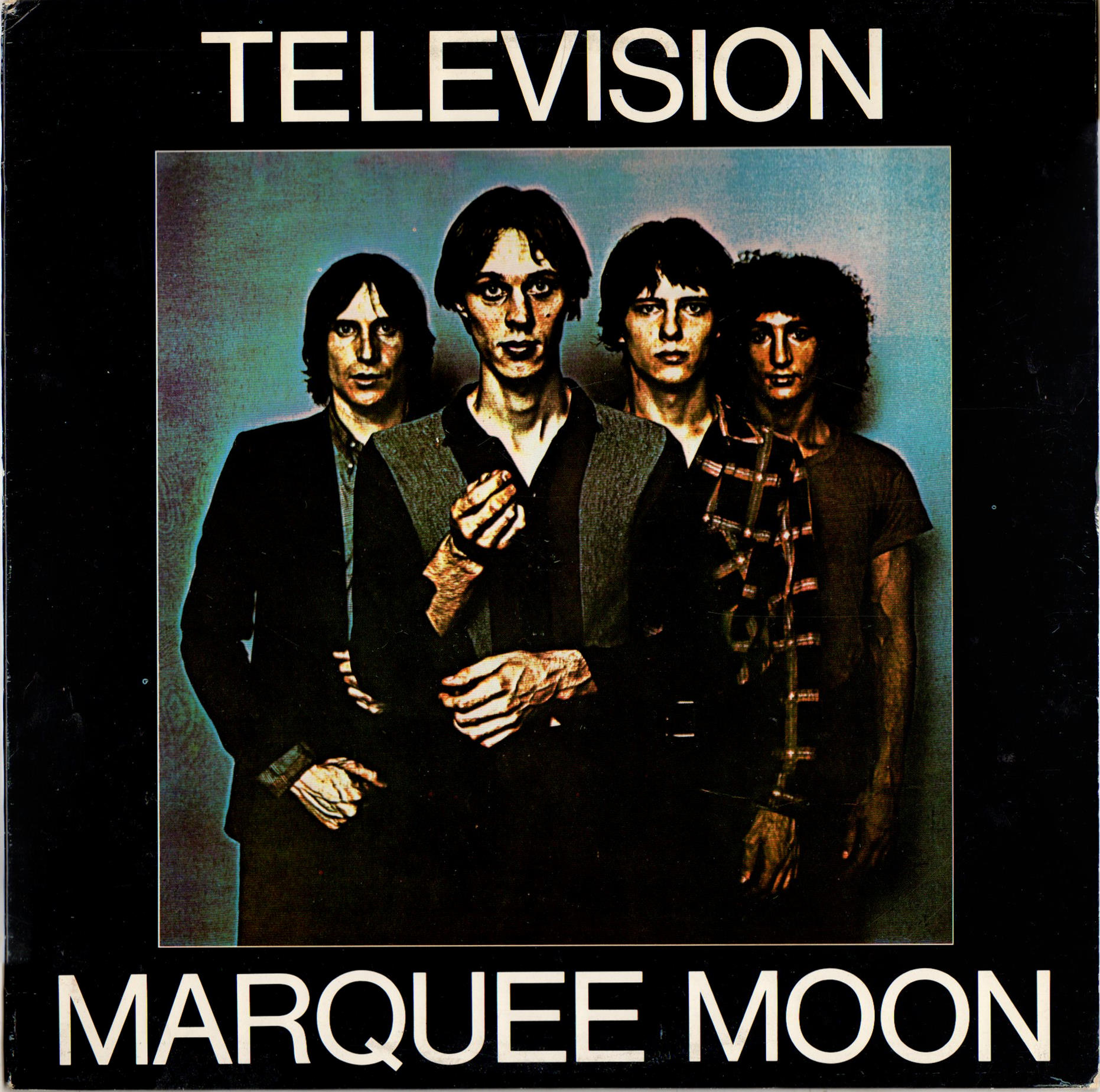

Tom Verlaine died on January 28, 2023. He was the guitarist, singer, songwriter for, and co-founder of the band Television. Their first album "Marque Moon", released in February 1977, is a masterpiece and, like all masterpieces, an expression of a unique talent and sensibility that fits in no category or genre. But the media and the streaming services insist that "Marquee Moon" is a "punk" album and Television was a "punk" band. Verlaine, himself, disdained the "p-word," and the media's insistence on categorizing his music as "punk rock" was an irritant that undoubtedly contributed to his media wariness and reluctance to do interviews.

But as Verlaine learned, labels once applied are near impossible to remove by the labeled. His obituary in The New York Times used the word "punk" in the headline and twice in the first sentence but accurately stated that his music was not easily categorized. Other major media were not so perceptive. The Washington Post headlined its obituary, "Tom Verlaine dies at 73; guitarist co-founded the punk band Television." NPR's first sentence read, "Tom Verlaine, a founding father of American punk and a fixture of the 1970s New York rock scene, died Sunday in Manhattan due to a brief illness." Rolling Stone magazine headlined its obit, "Tom Verlaine, singer and guitarist of punk legends Television, dead at 73,” and then proceeded to use the "p-word" ten times.

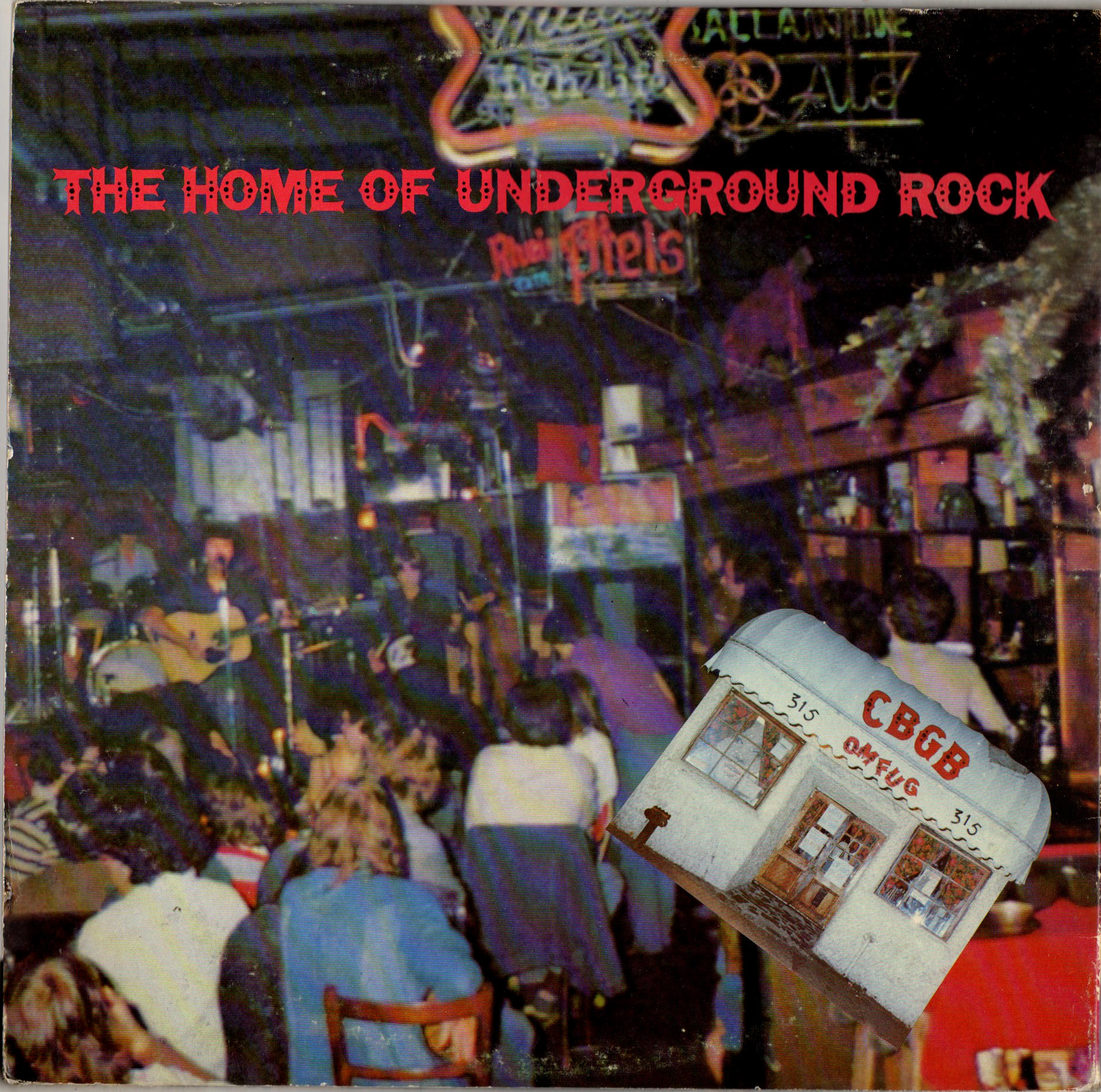

Yes, Television was the first band still remembered to play at CBGB, and along with Patti Smith, the Ramones, Blondie, and the Talking Heads, were the headliners and creators of a scene that later, much later, was hailed as the beginning of "punk." I can't explain why. The bands had little in common with each other, and the Ramones aside, even less in common with the flood of what came to be called "punk" bands in the U.K. and U.S. post 1977.

The story of capital "P" "Punk," now an officially recognized genre by the ever busy popular music taxonomists, is one of the great origin stories of rock. It's just waiting to be made into a Marvel movie. We have the forces of evil—self-important, arrogant rock stars, creating pretentious epics that emphasized long, indulgent solos and—virtuosity, (Not that! Oh, the humanity!) fooling the people, and denying them the simple music with simple slogans they deserved and really desired and all of this fostered by the truly abominable overlords who pulled the strings-- the record company businessmen. There must be heroes, and we have a scruffy bunch of leather clad underdogs in mid-70s New York City playing at CBGB, a dive bar on The Bowery, the only place that will let them on a stage, and they have only three chords and yes, of course, and always, THE TRUTH and nothing else to fight with except their passion. They will not let this stand, and they revolt. The war is long with many phases—punk, hardcore, grunge, post punk—but the forces of good triumph and the pernicious doctrines of complexity, competency, and key changes are forever consigned to the dustbin of history.

That's a good story. Simple, easy to understand and dramatic. It's the story that has been told repeatedly and has become history. The past doesn't exist except in stories, and the stories keep changing. They call that "revisionist history." I was, if not "part" of the "punk scene," at least "there" or "around." There are lots of stories. Everybody who went to the clubs and bought the records has a story. Here's my story. I think it's true, but then it's my story.

In my story, "punk" starts in the fall of 1973 with the release of the Rolling Stones' album, Goats Head Soup. The Stones were idols- "the world's greatest rock 'n roll band," and their albums were wild, sexy, and sometimes disturbing messages to youth. Even the square kids in high school loved the Stones, and you could hear "Honky Tonk Women" being played on multiple eight tracks every night in the McDonald's parking lot. We thought the Stones were like us and spoke for us. We were young, and it's easy to be fooled when you're young because you want to believe.

I bought Goats Head Soup when it hit the stores. The cover was ugly and perplexing. Jagger on the front and Richards on the back? Aren't they a band anymore? The music was bland and boring—the trite, sentimental "Angie," some filler songs--- "Can You Hear the Music?" being the worst, some generic Stones rockers, and the truly dreadful and ridiculous "Dancing With Mr. D."

The album made number one because it was the Stones, but nobody liked it very much. I constantly heard Brothers and Sisters by the Allman Brothers and Elton John's Goodbye Yellow Brick Road in my college dorm but not Goats Head Soup. My friends shrugged off the disappointment, "Maybe the next one will be better." It bothered me, though, for all our faith, devotion and idolatry, never mind our money, I felt the Stones owed us more than Goats Head Soup. Had Mick and Keith, now that they lived on the Riviera, were over thirty, and hanging out with jet set royalty, become boring old farts who thought they could put out mediocre or worse Rolling Stones albums and make money forever? Of course, that could never happen. I felt guilty for being so cynical. But they had made me cynical. Once you become cynical, you just become more cynical.

The Who, my other favorite band, released their Quadrophenia album a few months later. I tried to like it but thought it was pretentious, narcissistic, bombastic, and full of fake emotion. I saw one of the shows on the 1974 U.S. tour and it was professional, "you got your jumps, you got your windmills, microphone twirling and the hits, so you got your money's worth" arena rock. I had seen the Who in August 1971 in a midsize hall and stood applauding with the rest of the audience for twenty minutes after three encores, while the crew broke down the stage. Standing there, I was convinced I had experienced something extraordinary that I would never forget and I haven't. It was the greatest rock concert I've ever seen. In 1974, I left the arena feeling that I had seen the Who pretending to be the Who I had seen in 1971. Who were they? They even had the gall to call their next album, "The Who By Numbers."

In 1974, the charts were dominated by Elton John, John Denver, Grand Funk Railroad, and the soft "but nobody was a dad yet" guitar rock of Eric Clapton's 461 Ocean Boulevard. My music friend Shane and I thought it was all crap, youth-zak, foisted on us by the record companies. So, instead, we listened to John Cale's Fear, Eno's Here Come The Warm Jets and unfashionable British bands like Roxy Music, King Crimson, Mott The Hoople and Gentle Giant with a sprinkling of American eccentrics like Captain Beefheart, Randy Newman, and Tom Waits. The only charting artists we liked were Lou Reed and David Bowie.

We decided that rock was cyclical and in a bad period, so we looked to the past and watched for signs of the rock 'n roll resurgence that was sure to come. In the meantime, inspired by Greg Shaw's Bomp magazine, which fervently preached the gospel of 60s pop and garage rock, we searched out albums by the Troggs, Small Faces, Pretty Things, Zombies, etc., etc.

We played Nuggets, Lenny Kaye's groundbreaking '60s garage rock compilation, constantly, and thought the best track on the set was the Thirteenth Floor Elevators' "You're Gonna Miss Me," which seemed to us a typical teen macho, pissed-off, kiss-off to the snooty ex-girlfriend, bashed out by some three chord wonder Texas kids, who, like the Count Five and others, were able to grab hold of the rock 'n roll brass ring for two minutes and thirty seconds before dropping it and fading back into the obscurity of car washes, gas stations or, if lucky, daddy's business.

We knew no better until a record trading buddy sent me, unsolicited, a copy of the then obscure Thirteenth Floor Elevators' Psychedelic Sounds album. It was intense, strange, brilliant, so drugged out they were speaking in tongues, rock 'n roll madness and nothing like the spacy, folk-blues, easy listening San Francisco psych. The song "Fire Engine" conjured up a mind racing out of control towards insight or insanity or maybe both. Over someone howling like a siren, weird electric jug noises, pounding drums, and charging guitars, Roky Erickson sang, "Let me take you to the empty place in my fire engine, it can drive you out of your mind, climb the ladder of your own design in my fire engine." The Elevators didn't sound like Woodstock hippies on acid—peace, love, and oneness-- they sounded like the '66 Rolling Stones on a seven days and counting amphetamine jag, demanding that you get as brain fried crazy as they were. And they rocked harder than the Stones. We didn't play the record for anyone else. No one would understand.

Yeah, we were smart enough to know that anything we liked would never be popular. The jukebox in our favorite bar, amidst Linda Ronstadt, Jim Croce, Olivia Newton John, early disco records, and the constantly played "Ramblin' Man," only had one record we liked, "Born To Be Wild" by Blue Oyster Cult. We played it several times a night, but everyone else seemed to hate it. Finally, after the third or fourth play one night, some frat guys lifted up and tipped the juke box to make the tone arm skip to the end so they could listen to "Kung Fu Fighting." It wasn't easy for us. Bruce Springsteen should write a song about us and our devotion to rock 'n roll and our sufferings for it.

In 1975, we saw the first, long awaited signs of the rock resurgence. The Village Voice began to publish articles about a rock scene centered around a Bowery club called CBGB. Patti Smith, who we knew of as a rock critic and lyricist for Blue Oyster Cult, had a band, and there were other bands that we had never heard of before called "Television," "Talking Heads," and "Ramones." It was hard to imagine what these bands sounded like. The Voice made comparisons to the New York Dolls, Lou Reed, David Bowie, The Dictators, and Blue Oyster Cult. Talking Heads were described as "flamenco rock." We were puzzled, but we were in upstate New York without a car or money to get to Manhattan. A guy who had been to CBGB and seen Television play told us they were "like the Grateful Dead without acid." That didn't help. We were still puzzled.

In November 1975, Patti Smith's Horses album was released. Its mixture of arty poetics and basic garage rock was unprecedented and in the context of the time with Neil Sedaka, Elton John, and Silver Convention's "Fly Robin Fly" (Don't believe the revisionist history. Most early disco did suck), topping the charts, it was a shocking listen. Shane and I played the record constantly for friends and were met with incredulity, "She can't sing, she’s just ranting like a crazy person, the words don't make any sense, and those guys can't play." Privately, we agreed that the band was only marginally competent and really didn't rock. Patti's singing and words were overly dramatic and the whole package was selling attitude and style, but it had rock 'n roll energy. It gave us hope that the CBGB bands would be the rock resurgence we were looking for.

In early 1976, I saw an ad in Trouser Press and mail ordered Television's "Little Johnny Jewel" 7" 45 rpm. It was on a "do-it-yourself" label, Ork Records, owned by their manager, which was very unusual at the time. One nearly eight minute song was on the record, starting on A and running over onto B. It began with a repeated three note bass line, and then there was guitar picking below the bridge, strange note choices, and wide string bends for more than a minute, all of it musical and coherent over the rhythm section playing the spacy, open-ended groove. The rhythm guitar came in, the band went into tempo and Verlaine began to sing in his odd, thin, affectless voice, hipster semi-reciting what seemed to be a tribute to John Coltrane. "He's just trying to tell a vision, some thought this was sad, others thought it mad." At the end of the first side, Verlaine said, "and he loses his senses." The music picked up on side B with the band going free form for a chorus and Verlaine playing some very abstract sounds (Could he have heard Derek Bailey?) before they went into tempo again, and he played an incredible guitar solo that kept building increasingly intense variations on the same melodic idea with a piercing, wailing, Coltrane circa '65 like tone, while the rest of the band was fluid and grooved hard.

It was psychedelic music for the mind and body--- oddly reminiscent of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. But that had to be coincidence, of course, because nobody knew about them except us. It was a rock version of "spiritual jazz" – striving toward other planes of now, with intense, focused playing and no rambling, hippy trippyness. I was convinced that Television was a great rock band that was probably going to make a masterpiece album and that the CBGB scene was making rock music exciting again. I couldn't wait for the Ramones album.

A few months later, in April 1976, The Ramones arrived. To my dismay, it didn't sound anything like Television. It's hard to overstate the shock and disorientation that listening to the Ramones album for the first time caused Shane and me. The record was avantgarde and revolutionary--it rejected almost all rock orthodoxy. Still, at the same time, it was stupid and laughably incompetent by any musical standard other than Ramones music. We listened to the record, and when it ended, Shane said. "Are they serious?"

That was a good question. Were the Ramones just four surly, not very bright losers that had, on a steady diet of Slade, Black Sabbath, horror movies, The National Enquirer, handfuls of downs and quarts of Budweiser, transformed themselves into an uber-moron rock band, or were they Downtown art school guys, who, while sipping absinthe, smoking Gauloises and discussing Duchamp and Adorno, had decided to create a conceptual art project? "The two supreme examples of the melding of image, attitude, and music in history are the Beatles and the Velvet Underground. We'll put them together and create the worst, most offensive rock band ever and see what happens."

The Ramones caused the Great Rock Schism. Like the great schisms that have divided religions throughout history, there was a doctrinal set of beliefs regarded as essential to the rock faith that the Ramones rejected. Those beliefs were the bedrock principles of Black American music and eventually rock 'n roll—swing, the blues, and improvisation. The choppy, stiff, ultra-fast, groove-less tempos of the Ramones were the antithesis of swing. Their chords and melodies abandoned the blues feeling and structure. There were no solos or any interplay between the instruments and strict adherence to only the most rudimentary instrumental technique.

Energy, guitars, and attitude did not mean that the Ramones were playing rock 'n roll music. There was no "roll." They were playing a white bread version of pop that came to be called "punk" and were the sole originators of that new genre. None of the other CBGB bands sounded like them. Not the ones that became well known, Blondie, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Television, or the obscure ones either. A double live album was recorded at CBGB in June 1976 featuring eight lesser known, mostly forgotten bands that were playing regularly at the club. The music ranges from generic hard rock to power pop, to Van Morrison style R&B and even early Yes. Not one band sounds remotely like the Ramones. Punk did not originate on the scene at CBGB. The Ramones brought it there.

In the early days, most of the Ramones' audience were hipsters, and hipsters need to be different. If everyone else liked disco or bland, tuneful pop and preening, pompous, narcissistic rock stars, they would like four droogs playing lowbrow music that couldn't be danced to. The Ramones were different. Liking them was a statement. The hipsters loved not so much the music as they did the concept of the Ramones. The band was a middle finger to the rock scene and mainstream culture. I had progressed beyond "cynical" to "alienated," so I liked the Ramones. I had become a hipster. I liked Television much more, though, and the Nuggets style 60s garage bands were better dumb fun.

That spring, I saw Television play at a warehouse converted into a club in Boston. They walked out onto the stage wearing jeans, sneakers, and T-shirts, just like most of the audience, and the guitars began playing a wired up, mind drill, chord pattern. I knew I had heard it dozens of times. "It couldn't be…yes it was…The Thirteenth Floor Elevators!" Verlaine began singing, "Let me take you to the empty place in my fire engine." It wasn't a straight up cover version, though. He changed the lyrics, "Pull a hook and ladder right through your brain in my fire engine…We'll go rolling down to look at all the flames." It was a demand and a promise, "Get on board, we're going to take you some place you've never been." I was on board, howling like a siren.

"Little Johnny Jewel" lasted at least fifteen, maybe twenty minutes, with Verlaine's solo going farther out than on the record, exploring sounds with that penetrating, vocal Coltrane cry. There was no rock star showmanship. The band stood still and, other than glancing at each other for cues, seemed lost in the music. Verlaine only spoke to complain about the P.A. I remember much of the audience leaving. I don't remember anyone dancing. The music made me dance in my brain.

A rock 'n roll band equally influenced by the Thirteenth Floor Elevators and Coltrane was the band I had been looking for, and I knew they'd never be popular.

In October 1976, I saw the Ramones and the Talking Heads on a Friday night double bill at Max's Kansas City in New York. The audience seemed to be divided between arty types there to see the Talking Heads and rowdy Ramones fans, some of whom were dressed like the band.

A German couple sitting at our table was taking pictures of the club and the audience. Both the man and the woman had very short, spiked hair, which I had never seen before. They told me they were professional photographers who had read about the New York Scene in a magazine in London and decided to visit and take pictures. They asked me about CBGB and the best place to photograph "punks." I don't think I had ever heard the word "punks" used to describe a group like "Democrats," "Republicans," or the "4H Club" before. I said that I didn't know any "punks," thinking to myself, "whatever that means."

I asked about the scene in London, and the woman said, "They fight and spit at the groups."

I thought I had to be misunderstanding her. "Spit?"

"Yes, they spit."

"Who spits?"

"The punks."

"Why?"

She shrugged. "It's what they do."

The German couple took lots of pictures of the Ramones and their fans but left early. They were probably disappointed by the lack of fighting and spitting.

In November 1976, the first Sex Pistols single, "Anarchy In The U.K.," was released. When I heard Johnny Rotten's demented, enraged raving over the band's ultra violence take on the Who Live At Leeds, I knew they would never be popular in the U.S., maybe Iggy Pop-ular, but not played on real radio popular. For chrissakes, the guy claimed in the first two lines to be an anti-christ and then an anarchist! Donna Summer in "Love To Love You Baby," getting down with her bad self on the radio, now that was good, smutty fun and made #2, but some maniac insulting Jesus, screaming f-words and British gobbledygook, was not going to get played after Rod Stewart's "Tonight's The Night." You could take that to the bank. Rod could too.

Soon after "Anarchy In The U.K." was released and banned by the BBC, the Pistols used the f-word on British TV and became a media sensation. Young kids, listening to loud aggressive music, being offensive, uttering foolish slogans, taking drugs and fighting with the police, all sounded like the same old youth culture. But, no, these punks, they were different. They were "anarchists," and look at how they dressed—ripped clothes, short hair, chains, leather, safety pins through their cheeks---oh dear me. If they'd only act sensibly like those Rolling Stones.

The British media couldn't leave the punks alone. They were so damned photogenic. But the U.S. above ground music press turned a blind eye. Rolling Stone had ignored the New York Scene, and now they did the same to London. The rock fanzines and the British music mags NME and Sounds, readily available here, kept the few of us who cared up to date on the U.K. scene.

In Britain, the Sex Pistols had three top ten singles, and there were hundreds of punk bands, many of them putting out records, but that meant less than zero in the U.S. U.K. punk received no commercial radio airplay here. Life "on the scene" was little changed. Disco was still popular, and all the bands, later to be called "dinosaurs," were still trundling through the arenas, smoke machines in tow.

I was living in Boston and going to the clubs regularly. In early '77, I started seeing occasional pairs of spiked hair punks wearing leather, chains, and carefully ripped T-shirts with scrawled in magic marker slogans. "I HATE DISCO" seemed to be a popular one which was a safe sentiment to wear on your chest in a rock club in those days. But the punks were few. Most of the audience was the coterie of people who were "on the scene" that I saw at almost every show I went to, plus students and young working people out for a night of music and partying. A few bands playing the clubs sounded like the Ramones but most were "Boston Rock"--- hard rocking Bad Company clones or '60s garage style bands with a Bowie/Reed/NY Dolls edge. The rock critics who didn't work for Rolling Stone seemed convinced that the Sex Pistols and a horde of British punks would conquer America. I didn't see any evidence of that, but it's a lot hipper and more fun to write about punks than Olivia Newton John.

I saw the Ramones in January 1977 and the club was packed, mostly with scene people and a few punks. The dance floor was empty except for the punks who were just standing there shaking in place until one of the long time scenesters got out there and started pogoing. I had never seen anyone pogo before. Soon the punks were hopping up and down with their hands in the air. The guy had read about it in a magazine. Thank God he didn't start spitting.

Television's Marquee Moon was released in February 1977. By the time the album was recorded, Television were experienced, skilled musicians that had created a tight, unique band sound by gigging and hundreds of hours rehearsing Verlaine's intricate compositions and arrangements that were full of counterpoint, odd melodic structures, unusual rhythm shifts and for rock, strange chord changes. Richard Lloyd, influenced by Jeff Beck, was a talented guitarist, even more technically skilled than Verlaine and played beautifully structured, cliché free lines. He was a perfect foil for Verlaine. Fred Smith was an excellent bass player with a clear, penetrating sound, a melodic style and a strong groove. Billy Ficca, a sensitive, listening drummer in the Mitch Mitchell mold, played with a light, jazzy sound. Verlaine had a high, quavering voice, sang his poetic lyrics in a minimalistic speech like style and was a fine guitarist with a highly personal tone and a solo style that utilized unusual scales and ideas borrowed from free jazz saxophonists.

Marque Moon is neither "punk rock" nor "art rock" and not some mixture of the two either. It is something unique--"Spiritual Rock 'n Roll." Without making any overt references to spirituality, the music, like that of Verlaine's influences/idols, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and the Thirteenth Floor Elevators, is visionary and mystical, an expression of higher consciousness and an attempt to inspire us to transcend the ugliness of the world and lose "our sense of human" in ecstasy. Verlaine said, "Each one [of the songs] is like a little moment of discovery or releasing something or being in a certain time or place and having a certain understanding in something,"

Marquee Moon begins with the song "See No Evil" and the words, "What I want, I want NOW, and it's a whole lot more than 'anyhow.'" Immediately, Verlaine's talent for innovative arrangements is obvious. The song, like all of his songs, juxtaposes a short repeating melodic phrase played by one guitar against the other playing an interlocking rhythm pattern. Philip Glass' early music is structured similarly and probably influenced Verlaine. The effect can be best described as "stasis in motion" and creates an intense, focused feeling of concentration in the music that is called "spiritual "in jazz and "psychedelic" in rock.

"Venus" has one of Verlaine's best vocals, sounding wired and ecstatic. The lyric, "The world looked so thin and between my bones and skin, there stood another person who was a little, surprised to be face to face with a world so alive…. I fell right into the arms of Venus de Milo" is surrealistic zen enlightenment. Fred Smith's counter melodies, a different one every time, under the guitars on the chorus are beautiful playing in the McCartney/Casady style. Verlaine's solo begins with violin sounds, and then he plays 24 bars of melody that hints at blues feeling while slipping in and out of a scale, a technique he frequently used to create in his playing a free, mysterious feeling.

"Friction" is one of Television's most rocking songs. Over Lloyd's superb Keith style rhythm guitar, Verlaine plays some absolutely wild guitar sounds and ends his solo with some fretboard spanning wails.

The song "Marquee Moon" is Television's masterpiece. Verlaine begins it by playing a repeating rhythm figure. Lloyd enters playing a four note melodic cell, and then Fred Smith plays a perfect two note bass groove. Billy Ficca comes in, nailing down the rhythm. The band continues playing their repeating parts, creating a swirling, spacy groove while Verlaine sings the first verse. "I remember, how the darkness doubled, I recall, lightning struck itself. I was listening, listening to the rain. I was hearing something else." They play a heraldic twelve bar melody and then play a third rocking theme under the chorus before repeating the whole sequence. After the second verse, Lloyd plays a short guitar solo, which is a beautiful paraphrase of the initial melody. After the third verse, with Lloyd playing the repeating rhythm figure and Ficca and Smith laying down a relaxed but insistent groove, Verlaine plays an extended raga-like guitar solo that is haunting and mysterious with a "seeking the beyond" quality. His melodies and abstract blues licks, in the mixolydian mode, used by Coltrane for "India" and Miles Davis for "All Blues," spiral on across the bar lines, never resolving, in ever increasing intensity, while Ficca plays cross rhythms. Verlaine's solo ends, and they play a fourth theme that repeats, building in intensity until released in a pounding rhythmic figure that climaxes and we hear chiming guitars that are like shining, otherworldly light. It's a sublimely beautiful moment.

"Elevation" exemplifies Verlaine's creativity and willingness to play with song form and mood. The verses have a dreamy, droning melody, but the choruses are pounding near hard rock. Lloyd's guitar solo is masterful with a thick tone and blues rock guitar intensity without the cliches.

"Guiding Light," co-written by Lloyd, is the Television version of a '60s soul ballad and is the most conventionally structured song on the album. Unfortunately, Verlaine doesn't have the vocal style and chops to put the uncharacteristically dramatic lyrics across.

"Prove It" is another one of Verlaine's oddly structured songs. The verses have a relaxed semi-reggae beat, and the choruses stop and start with aggressive guitar before going into big, bold chugging chords. Verlaine's vocal is one of his best, and he sounds at his most impassioned, dropping his cool to shout, "PROVE IT…JUST THE FACTS…." His guitar solo is intense and near shrieking like an overblown sax as it ascends a scale to finish with a burst of melody.

"Torn Curtain" is a beautiful minor melody that feels oppressive, like the weight of memories and years mentioned in the lyrics. The crying, lamenting tone of Verlaine's guitar solo is so vocal it almost sounds like he's playing with a slide. Over great drumming, he plays with slow burn intensity to a wailing climax.

The week Marque Moon was released, Hotel California was #1, and it, the A Star Is Born soundtrack, Rumours, Barry Manilow Live, and Linda Ronstadt's Simple Dreams filled the #1 spot for the rest of the year. In the fall, "You Light Up My Life" was the #1 single for ten weeks. Whatever happened to the Sex Pistols and all those punks?

The critics were positive but didn't seem to understand that the album was unique and innovative and opted either for the label "punk rock" or "art rock." Marque Moon flopped miserably, sank beneath the surface of the ocean of soft rock, and never made the U.S. top 200 chart. Reportedly it sold 80,000 copies which I find hard to believe, given the scarcity of used copies today.

Television toured as the opening act for Peter Gabriel to promote Marquee Moon. They were booed, and objects were tossed at them. They recorded a follow up album, Adventure, released in April 1978, which was quite good but lacked the transcendent spiritual passion of Marquee Moon. It sold even less well. The band broke up a few months later.

Around the clubs, I began to hear the term "New Wave." Sire, the Ramones' record company. took out ads imploring, "Don't call it punk." The record companies decided that "punk rock" would never be popular. The charts provided ample evidence. The Ramones' first two albums only reached numbers 111 and 148 on the Billboard chart. The Dead Boys' Young, Loud and Snotty topped out at #189. Richard Hell's Blank Generation didn't make the chart at all. The Sex Pistol's Never Mind… made #106. The first Clash album was deemed uncommercial by U.S. CBS and remained unreleased in the U.S. until 1979.

In 1978, Blondie, Devo, the Police, and the Talking Heads all bands that had been called, inaccurately, “punk” became popular but now were dubbed "New Wave Music." Even Public Image, the new band of John Lydon, the former Sex Pistol, Johnny Rotten, was playing an arty form of rock and using dance and dub rhythms. In the clubs, keyboards, dance beats, styled hair, and even suits became common.

Punk had never been a significant commercial force in the U.S. In 1978, the record companies, the media, the musicians, and the audience all realized it would always be a beneath the underground phenomenon.

The Ramones didn't give up. They made albums aimed at the charts and radio but they stayed true to the punk verities--fast, loud and hard-- at live shows and driven by a tireless work ethic, they toured constantly. While never achieving mainstream success, they were the punk messengers and exemplars.

In 1981, I began to hear bands like Minor Threat, Bad Brains, Husker Du, Black Flag, and others that were being called "hardcore punk" on college radio. All were obviously heavily influenced by the Ramones, and to me, hardcore sounded like Ramones music but played even faster with tuneless, unintelligible, shouted vocals.

Hardcore, not the CBGB scene, was the true beginning of what is called "punk rock" today. It rigidly defined the musical style of "punk," gave rise to the DIY aesthetic, and created a vibrant counterculture.

I didn't like the music. I was close to thirty. I was too old.

___________________

Marquee Moon was excellently recorded by Andy Johns who had worked on Exile On Main Street, Led Zeppelin albums, Hendrix albums, and Free's Highway. He knew how to record electric guitars. The band played live in the studio, and Johns got a dynamic, thick, exciting guitar sound onto tape. Reportedly, “Marquee Moon” was recorded in one take which Billy Ficca thought was a rehearsal.

It's a classically simple, almost throwback recording. Johns didn't use any studio trickery or effects. One guitar on the left, one on the right, bass, drums and Verlaine’s vocal in the middle. Little overdubbing was done, except some doubling of Lloyd's solos.

Soundstage is wide and moderately deep. The bass is well recorded but not bottom octave low. The recording closely approximates what the band sounded like live at their best. For a rock album recorded in 1976, it's a nearly miraculous recording.

Original Elektra pressings have a significant bit of shrillness in the treble. It could be on the original tape. It seems unlikely that the fault was in the mastering done by Greg Calbi and Lee Hulko at Sterling Sound. Possibly, there was a production or pressing flaw. I listened to a 2022 Rhino reissue pressed in Germany on black vinyl which played very quietly, and the shrillness was not audible. Some of the dynamic excitement of the original LP was missing, though.

RIP Tom Verlaine (1949-2023)

copyright 2023 by Joseph W. Washek and all rights reserved

.png)