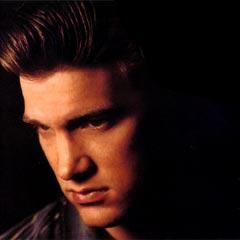

We Caught A Rising Star—Chris Isaak

Interview Originally Appeared 1987 In The Absolute Sound

Back in 1987, I interviewed the young up and coming and not particularly well-known Warner Brothers recording artist Chris Isaak. Thanks to a reasonably successful recording career, an effective and consistent live show, and an unusual “reality”-type comedy series on Showtime, Isaak divides his celebrity between being a respected recording artist, and a campy “celebrity,” known in some quarters simply for being known.

With his swept-back ‘50’s hair and Eddie Cochrane-like haberdashery, Chet Baker-ish schnozz, hollow body electric guitar and especially his shiver-inducing, close-to-the-microphone intimate wail, Isaak was heralded as both a musical throwback and a “new” Roy Orbison at a time when “New Wave,” synth-based “hair bands” still dominated radio airplay.

Unfortunately, while the sound of Isaak’s first two LPs (both issues on vinyl) was not bad by late 1980’s standards, it couldn’t match the sound Bill Porter managed, recording both Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley—an apt comparison since Isaak’s voice hinted at both of them. Ironically, compared to much of today’s Pro-Tools polluted sonic swill, those 1980’s records sound mighty inviting!

However, at the time, I decided to use the interview opportunity to lobby Isaak to pay more attention to sound quality on his next record.

Isaak had recently sold out New York City’s late, lamented Bottom Line, in May and July of 1987, while opening for The Thompson Twins (!) at a much larger venue. Demand swelled for yet another Bottom Line appearance, and when that was scheduled, in August of 1987, so was the interview.

I met with Isaak at Warner Brothers Rockefeller Center headquarters the afternoon of his Bottom Line show (which I was fortunate to attend).The interview and show made clear that while Isaak struck some retro-poses in his looks, dress and music, he was no poseur. He has drawn from the masters, but he hasn’t sucked their musical blood.

Isaak is no musical vampire. On the other hand, he can sometimes be so glib and off-hand, both on stage and in the interviewee’s hot seat, that he takes on a David Letterman-like quality; you aren’t sure whether he’s being serious or doing a well-orchestrated parody.

Other times, you think you’re just experiencing a well-restored, customized version of an old product—like a mint ’57 Chevy that’s been turbocharged. You get the sense that, as an adolescent, Isak sat in his Stockton (California) home listening to early rock and roll on the radio when it was fresh and new, telling himself, “I can do that, and when I grow up, I will.” And he’s still stuck in that musical realm, proving his childhood fantasy.

On stage with his band, Isaak is clearly the group leader. There’s no partnership a la Jagger/Richard between him and guitarist James Calvin Wilsey. There’s no haberdashery democracy either, as there was with the dress-alike early Beatles. Instead, the stage picture consists of bassist Rowland Salley stage-right, Wilsey stage-left, and drummer Kenny Dale Johnson behind on a riser, all dressed in cool grey suits. But Isaak, stage center, wears electric blue lamé.

He could be Conrad Birdie in a summer stock production of Bye Bye Birdie. Or he could come across as even more pathetic. But he doesn’t. And that is part of the fascination. It takes guts to get on stage looking like a parody. It would be so much easier for Isaak to dress in something unique and contemporary. But you get the idea that he feels he must earn his way to the top by retracing the great steps of rock and roll, carrying the white man’s musical burden.

Not that Isaak is on some sort of serious historical quest. His stage persona suggests quite the opposite. He is the most skilled musician-monologist I’ve seen on stage since Springsteen, and a hell of a lot funnier, exhibiting an incisor-like wit, dripping with nasty sarcasm. Isaak isn’t against being the butt of his own humor, but he really shovels it out at the other band members.

Not because of their playing, certainly. Bassist Salley plays fast, clean, muscular, and very deep. Drummer Johnson looks pained throughout the set but delivers hard, though seemingly unsophisticated support a la Ringo Starr, while Wilsey’s guitar rings and shimmers and fills in the sound with grace and taste.

Hearing Chris Isaak and band live only emphasizes the technical inadequacies of his recordings. Will our chat influence his next record? You’ll have to judge that for yourself. But just to be sure, at the end of the interview, I gave Isaak a 90 minute cassette or Presley, Orbison and The Everly Brothers dubbed off my Oracle turntable onto a Nakamichi BX-300. Of course, Isaak was familiar with all of these records. I just didn’t know if he’d heard them properly decoded.

Face to face, I sized Isaak up as a wise guy and prepared myself for a battle of wits. I got one, but in print you’ll have to sometimes read between the lines to experience it. And once Isaak understood the perspective from which I was coming, he dove right in!

CI: Who do you write for?

MF: A high-end audiophile magazine.

CI: That’s what this interview is for?

MF: Yes. I’m the popular music editor.

CI: Popular music? What does that have to do with me?

MF: I’m also the unpopular music editor.

CI: The RCA stuff that Elvis did, I think it’s some of the best sounding…the quality of the sound for the time it was. People always say, “Well nowadays we got the compact disk, we got this and that,” and they say “That stuff doesn’t stand up.” Well, crank that stuff up in your car, and crank up anything else you want to play and it stands up fine!...It’s always interesting, half the time you talk to these guys (older heroes, whether musicians or engineers), and they say, “Yeah, I got that sound, but I don’t want to do that anymore, now we’ve got digital recording…” A lot of times you go back to your hero and you go, “What a great sound you had on those old Gretsches.” And he goes “Gretsch? Peavey, man! Tube amp? Forget the tube amps, we got this new one,” and you kind of just go, “Oh God!”

MF: How conscious are you of sound quality?

CI: Very.

MF: I think you have created a musical and visual image that blends Fifties and Eighties sensibilities into something new, but your recordings tend to produce a sonic clash of values to my ears.

CI: I try to get the Eighties sound. I think that to go back and say I want this to sound like a Fifties recording…There are some aspects of our sound that are old fashioned, or classic, or whatever you want to call it—the vocal being way on top of the mix—trying to leave a lot of space for the guitar, using echoes that are big and clear. My idea of a good echo is a big room sound. I always heard about the RCA building where they used a staircase or the church next door or some- thing. And Buddy Holly recording in a big ballroom, I think. They use actual big space. I like that kind of feeling. But there are certain things they do now on some stuff, for example, the punch of the electronic drums. That real heavy beautiful sound. The clarity of different tracks. I like that. People who don’t have trained ears or who aren’t listening carefully say, “Oh, you don’t use synthesizers and drum machines.” Well, they’re wrong. I’ve used drum machines, synthesizers, I’ve used multi-track and double-track and slave-tracked, cross cut—anyway I can, to get what I want.

MF: Do you think a live album of your performances would be effective?

CI: Could be. Certain songs would be good live, because I have a swinging band and they could cut it live.

MF: Have you thought about cutting a studio album “live”?

CI: I’ve thought about it because I work with Lee Herschberg as an engineer, and he’s worked with just about everybody I think is good, and he’s got so much experience. It’s like question-and-answer period with him. I mean I don’t even know to ask him intelligent questions, half the time. You describe to him what you want, and you get it. But I’d like to make a one-microphone recording with him. One mike in a roomand everybody sings…I’ve always liked recordings where people played live together. If you listen to the old Stones records you can kind of hear where the people in the room were standing, almost.

MF: Even in mono.

CI: It sounds like they’re in a room playing. And now it doesn’t sound like that. It sounds like the singer sings through that little speaker, but they don’t sound like they’re placed in a room, because there’s not an echo that’s all blending into one microphone, anywhere. I like the idea of going for a one-take recording and doing 25 takes, you know?...I bet you could take about 99 percent of the people out there singing today—big stars—and you put them in a one-track recording, and they’d be out of the business. They cannot sing! I think I can sing. There’s a lot of things I don’t have going for me, but I think I can sing.

MF: What don’t you have?

CI: Musically, I don’t know how good a songwriter I’m going to be. And as a singer, I think I have a pretty good voice, but I don’t know about my style. I’m still trying to find my own strong style. In songwriting, when you compare yourself to someone like John Lennon, you feel like shooting yourself.

MF: Everybody does.

CI: I met Roy Orbison. I wish I could have written one of the songs he’s done. I mean, he’s got 15 songs that I haven’t touched that height.

MF: Well you’re on your way. There is a lot of real emotion in your songs, compared to some of the wallpaper that’s out there….you write a lot in minor keys.

CI: I like that. I’ll probably continue to write a lot of stuff in minor key. I really like that sound. It’s up to me to expand. I’m trying to write a little bit on piano. I don’t know how to play piano, but I bought one. A real one.

End, Part 1

.png)