A Dance of Death, Now In HD

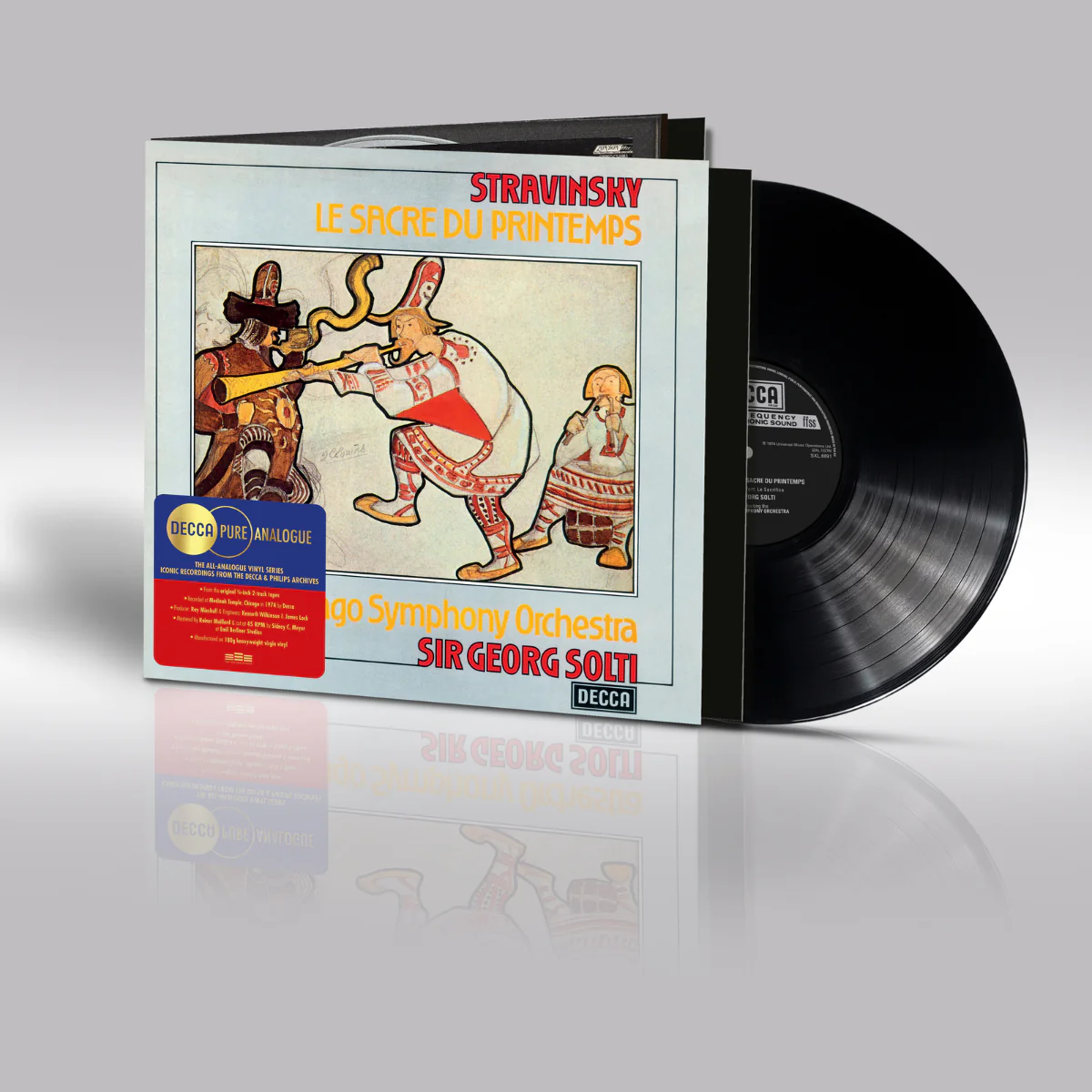

Decca Pure Analogue Brings New Clarity To 'The Rite Of Spring'

Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring), Igor Stravinsky’s primal ballet score, stands at the crossroads of much of music and art. Premiered in the spring of 1913 it sits ominously in between the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and the start of the first world war in 1914. All three pivotal events in retrospect, are seen as starting points of the modern age. But we must ask: why is this 35 minute ballet deserving of such historical weight? What makes it the point at which 19th century musical ideals suddenly turn obsolete?

The Rite is certainly a statement piece to open the new ‘Decca Pure Analogue’ series with. My colleagues Mark Ward and Paul Seydor have already written extraordinary coverage of the other two inaugural titles in this series: Willi Boskovsky’s New Years Day Concert in Vienna, and Colin Davis conducting Sibelius Symphonies No. 5 and 7. Those are excellent titles and contain important pieces of the repertoire, but the Rite occupies an almost mythic place in musical culture few works can aspire to.

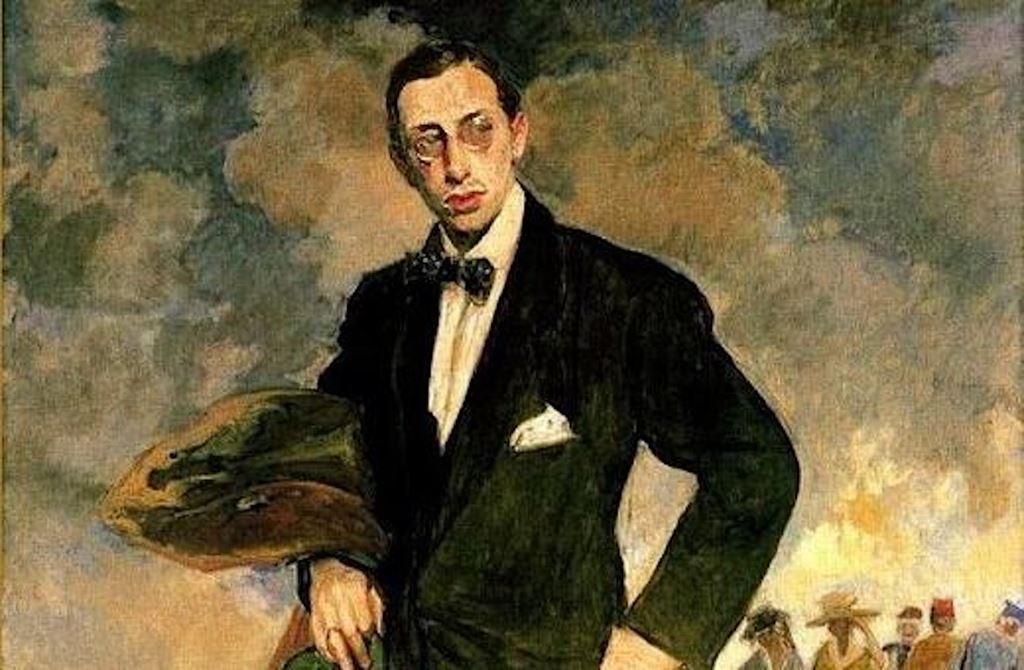

The events leading to the mythologizing of this work were not entirely organic. The young Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was beginning to make a name for himself at the turn of the century, a period which coincided nicely with the western European interest in music from the exotic empire. That drew Stravinsky to Paris, where he entered into a partnership with ballet producer and artistic financier Sergei Diaghilev. Diaghilev was the founder of the Ballets Russes, a dance company based in Paris started in 1909 to satiate the French appetite for exotic Russian culture. It was around this time that Diaghilev first heard the music of Stravinsky, and after working with him on a new orchestration of Chopin’s Les Sylphides, commissioned the composer to write a new ballet for his financially struggling troupe, this time based on Slavic folklore. The result was Stravinsky’s first major international hit: The Firebird (1910).

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

The Firebird struck the right chord with Parisian audiences, it drew heavily from Russian folklore elements in its staging, while still retaining the trappings of traditional European ballet. The music too was seen by the music press as continuing, if not perfecting the legacy established by The Mighty Five, the first generation of Russian nationalist composers (Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin and Mussorgsky were counted in this group).

Stravinsky continued his partnership with Diaghilev and premiered his next ballet, Petrushka in 1911. Petrushka, while incorporating more dissonance and angular rhythms into the score, was a further critical and financial success for both company and composer. Again, Stravinsky and his collaborators drew on Russian folklore, but this time with a more lighthearted and whimsical story. But even before Petrushka was finished, Stravinsky had in mind a musical setting much more shocking and violent.

The composer began working with Nikolas Roerich, a controversial painter, folklorist and archeologist (in the loosest possible application of the term) on a concept Stravinsky envisioned a year prior:

I had a fleeting vision, which came to me as a complete surprise. . . . I saw in imagination a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the god of spring. Such was the theme of the Sacre du Printemps.

Stravinsky didn’t just want to channel Russian exoticism through his new ballet, he wanted to resurrect pre-Christian mythology (or imagined mythology) in a way intended to shock the crowd. He worked with Roerich to incorporate numerous bits of Russian folk melodies into the score, even if the setting itself was more fantasy than history. But the real potential for controversy came from Stravisnky and Diaghilev commissioning dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky to create choreography for the ballet.

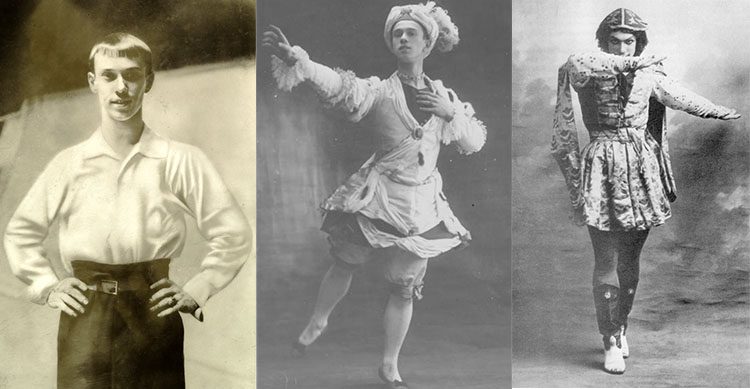

Nijinsky has made a significant stir in Paris around this time, creating daring choreography for Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun in 1912. Nijinsky took Debussy’s liquid and flowing score, and paired it with angular choreography that looked more like an Egyptian painting than the fluid motions of 19th century ballet.

Dancer and Choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky

Dancer and Choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky

Nijinsky went even farther in developing choreography for the Rite. To match the prehistoric costumes developed by Roerich, the dancer produced the most unromantic motions and gyrations consisting of limbs patterned in hard angles, bent knees, toes pointed inwards. The sacrificial maiden was stoic, covering her face at times, and never allowed to show the tragic emotion of her circumstance. This choreography was almost like that of a cave painting, where the figures are simple shapes cast in two dimensions, without detail or motivation.

The rehearsal schedule Nijinsky imposed on the Ballet Russes dancers was well-publicized and perhaps helped generate some of the opening night fervor. He demanded 120 hours of rehearsals to teach the dancers to move completely contrary to their lifelong training. Check out the Geoffry Ballet's reconstruction of Nijinsky's original choreography of the final sacrificial dance below:

But Stravinsky’s score was new and daring as well. The ballet ‘Introduction’ begins with a solo bassoon entering on a high C, extraordinarily high and difficult for bassoonists of the day, particularly on the French bassoon which is a slightly different instrument from the more universally used German design.

The opening bassoon solo

The opening bassoon solo

There are moments of screeching cacophony in The Rite, but its dominating characteristic is its use of rhythm and meter. Many musical sections in this score repeat continuously and are meant to highlight the rhythmic structure of the music much more than melodic elements, which at times can actually be incredibly tonal. Western tonality had more or less been expanding infinitely since the time of Wagner and his endless secondary-dominant chord progressions. Richard Strauss premiered his operas Salome and Elektra a few years prior to The Rite, and in many ways those works are more dissonant than Stravinsky’s Opus, but it was the total artistic performance of this ballet: The music, choreography, costumes, staging, and infamous premier, that solidified the work as a dividing line to modernism.

Costumes from the 1913 production

Costumes from the 1913 production

When the curtain finally rose on the ballet at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in May of 1913, the Parisian audience was ready for trouble. What happened next varies by accounts. When I was a young high school musician it was explained to me in a music appreciation class that Stravinsky’s score was so noisy and uproarious that it caused the Parisian audience to riot. In reality, it may have been a contributing factor, but most witness accounts state that the audience was so loud that by the time the ‘Augers of Spring’ began, the orchestra was completely drowned out, and much of Stravinsky’s score went completely unheard. Instead, much more ire was paid to the dancers and their costumes, which caused much ridicule from the discerning, ballet-loving crowd. Musicologist Richard Taruskin asserts that “it was not Stravinsky's music that did the shocking. It was the ugly earthbound lurching and stomping devised by Vaslav Nijinsky.”

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris

The commotion from the audience was not limited to jeers from those that disapproved of what they were seeing. There were also more “hip” concertgoers that began fighting with the naysayers, and multiple brawls spilled out onto the street outside the theater. The police eventually intervened and around 40 audience members were ejected with the performance allowed to finish, by some accounts in relative peace and quiet.

The critical press were split on whether The Rite of Spring was an important futuristic work of total art, or a nonsensical muddle of dissonance and distorted choreography. But all the coverage of the spectacle ensured the work remained in the repertory for good, especially as a concert work. It must be stated that part of what made The Rite so bold, is that it was incredibly difficult to play at the time. In addition to demands on the range and volume of the instrumentalists in the orchestra, the rhythmic patterns of the music are much more complex than any music that would be familiar to the average orchestra musician of the time.

I’ve played the piece a few times, although it’s been about a decade. What I remember most about the experience was that it was mostly an exercise in counting efficiently. As far as learning notes, other Stravinsky works such as The Firebird are much more demanding, but The Rite is much more about counting and understanding the mixed meter patterns. But these are skills that have been cultivated from 100 years of musical development in the years since Stravinsky’s opus debuted, and it took many years for the piece to start sounding confident when performed by orchestras.

A Recorded Legacy

Just because orchestras had difficulty with The Rite for many years, doesn’t mean they didn’t play it. The work became quite popular after the First World War, and made its mark on the early commercial recording scene. However, having listened to a few of these earlier mono, and even stereo recordings of the piece, many are quite ragged. That changed in 1959 when Leonard Bernstein released his 1958 stereo recording (MS 6010) which did much to raise the playing standard of the work and set a new benchmark of what is possible in regards to Stravinsky’s score. After the Bernstein, numerous recordings of The Rite were released, each aiming for greater rhythmic clarity, technical cleanliness, and dynamic power. That of course brings us to the recording Decca Pure Analogue has to chosen to kick off its reissue series, Georg Solti’s 1974 recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on Decca in the U.K. and London in the USA.

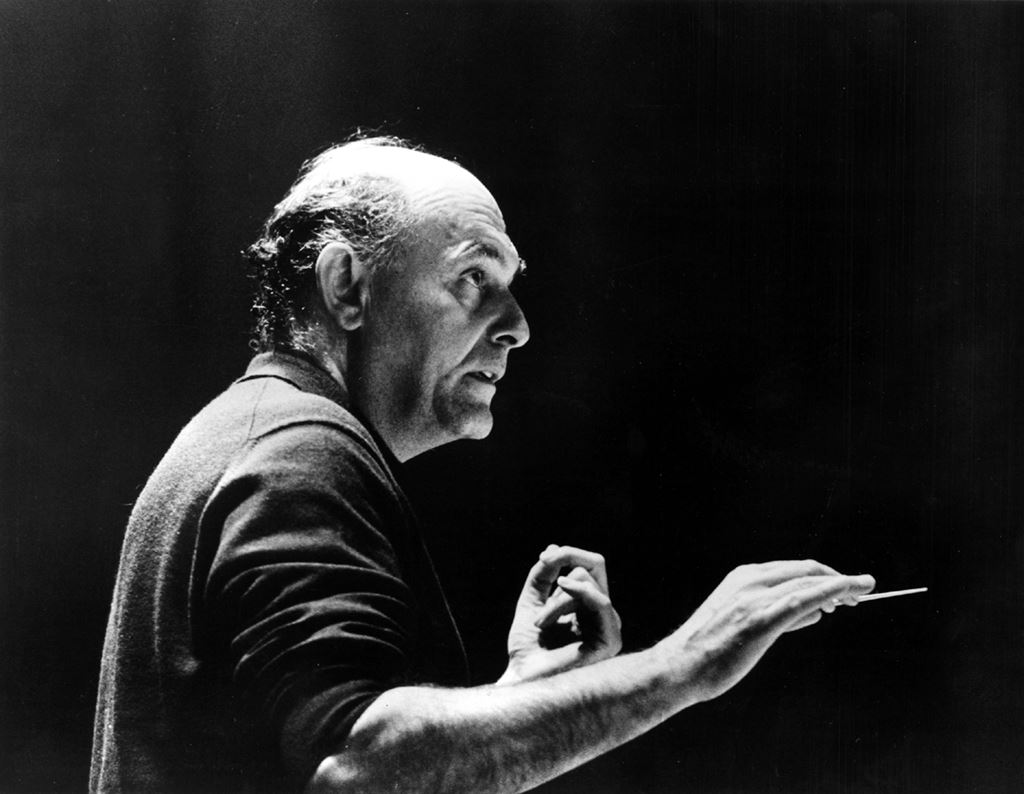

Hungarian conductor Georg Solti (1912-1997) was one of Decca’s key recording artists in the 1960s and 70s, initially making a strong name for himself as an opera conductor in Europe. In 1961 he had been appointed the music director of Covent Garden in London and did much to raise the standards and international notoriety of the company during his tenure. It was that reputation that landed him not one, but two separate job offers from the imperiled Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the late 1960s.

Sir Georg Solti, music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1969-1991

Sir Georg Solti, music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1969-1991

You see, the CSO had come into maturity under the baton of another Hungarian maestro: Fritz Reiner (with whom the orchestra recorded its famed Living Stereo LPs). Reiner was a demanding technician who significantly raised the standards of the orchestra. But after his death in 1963, the CSO found itself artistically adrift and with overwhelming financial woes. After a string of conductors and temporary fixes that were not a good fit for either party, the CSO thought they found their answer with Georg Solti, the conductor they originally offered the job to after Reiner’s death in ’63, but who was now finally able to accept the post in 1969.

Solti was the breath of fresh air the group needed. Under his leadership, the CSO toured internationally, recorded incessantly, and became one of the most talked-about ensembles around the globe. All of this effort transformed the organization's finances as well and set it on the path to economic stability.

Solti’s programming on the stage and on record was ambitious. Some of the first sessions he directed with the orchestra were complete recordings of Mahler’s 5th and 6th symphonies. 1974 was a particularly busy year for the ensemble as Solti led it in recordings of the complete Beethoven symphonies. Yet after taking it on tour to Carnegie Hall earlier that year, he still found time to squeeze in Stravinsky’s bold opus.

This session, recorded by Decca stalwarts Kenneth Wilkinson, James Lock, and Peter van Biene, was done in Medinah Temple, across the street from Orchestra Hall in Chicago. Orchestra Hall had been the site of RCA’s famed 1950s recordings, however as noted in the insert accompanying this Decca Pure Analogue edition, renovations to Orchestra Hall, including the addition of an air conditioning system in the mid 1960s, had rendered the space less than ideal for recording. Medinah, while not everyone’s first choice, was far superior to the compromised environment of Orchestra Hall and had the convenience of being located a stone's throw from the group’s home venue.

I’ve long considered this recording one of my favorite 70s Deccas for both performance and sound. Solti’s experience as an opera and ballet conductor shines here, giving the musicians just enough rein to shine soloistically, but keeping the pace and rhythm going with focused intensity.

This is one of the most played, most performed works in the orchestral cannon by the time the second half of the 20th century rolls around. Because of this, I cannot begin to compile and compare an exhaustive list of recordings to hear how this old favorite stacks up. I will say I grew up with Bernstein’s 1958 account, and in many ways that version holds a special place in my heart. However, that version is also of an older style, one in which Stravinsky’s modern angularity is performed with a romantic phrasing structure and lots of moments of rubato taken by Bernstein. Solti’s rendition holds a bit more to the modern aesthetic, and is closer in pacing and drive to the composer’s own recording from 1961, although that one is a bit lighter in weight and aesthetic owing to the musical direction Stravinsky took in his composing after the second world war.

The real stars of this show are the CSO musicians, who play with power and confidence plus a cohesion that is remarkable even for this polished an ensemble. This is not a Rite that is for the sentimental, but one for rocking out to the driving primal rhythms of the ‘Sacrificial Dance’. Of course we are greeted with the clear power of Tracking Angle’s favorite solo trumpet Bud Herseth, and the manic wails and howls of Dale Clevenger making the first horn part sound much easier than it actually is. All the solo voices are at the top of their game here, and to me this session from 1974 represents the orchestra at the absolute peak of its reputation. This is the CSO I heard about growing up—powerful, abrasive, yet nimble and quick to turn on a dime.

Dale Clevenger, CSO principal horn from 1966-2013

Dale Clevenger, CSO principal horn from 1966-2013

Is this the absolute best interpretation of this work on record? I’m not sure but I doubt it. There are quite a few critical darlings out there, and if I were to be somewhat picky I do wish Solti brought out a bit more mystical energy in the subdued sections of this work. Bernstein does that, but the sound even on my (now exceedingly hard to find) Ryan K. Smith cut (Sony 88765476331) is a bit thin and lacking in any body. My other memorable recording that I own is the Muti with Philadelphia on EMI (ASD 3807). The performance is clean and full of energy, and sound on that pressing is better than the Bernstein, but still not in the same league as any iteration of the Decca. And still, when I hear this CSO performance I get transfixed on the manic energy of Stravinsky’s pagan score, and I think that is what this piece is supposed to invoke in the listener.

Stravinsky in HD

The team at Emil Berliner had a daunting task on their hands with this release, perhaps more so than anything they’ve done in recent memory. For their efforts in the Original Source series, they had the task of taking recordings that were not particularly well-regarded for sound, and showing the real genuine quality that was buried in the tapes. Well, for this release they had a different problem: how to improve on greatness.

Kenneth Wilkinson’s Decca/London LPs, pressed in the UK, have always been considered to be of extremely high fidelity. I have plenty of them and despite the transition to solid state in the 60s, these narrow-band Decca and London discs consistently impress me no matter what type and level of system I’m listening on. Now, that’s not to say they can’t be screwed up, as evidenced by the digital Abbey Road cut of this recording found in the “Decca Sound” box set from 2013. Our host shared with me his rip of that particular rendition and it didn’t sound much like what one wants out of a Kenneth Wilkinson two-track recording.

I do however own some other versions of this session on vinyl, including my original UK London (CS 6885) as well as the 2002 Speakers Corner pressing cut by Decca engineer Tony Hawkins. The original Decca/London narrow band pressing is just as much a sonic marvel as the day I brought it home roughly 12 years ago. Instruments are clear, clearly laid out, and dynamics are big, punchy, and at times scary. Most importantly however, this pressing gets the timbre of the instruments just right as to render a very convincing near live experience. Only a bit of smear at the dynamic peaks breaks the illusion for me, and I find that is often the one difficulty with the older pressings cut on more “mass-market” cutting setups.

My well tread, but still excellent sounding London original

My well tread, but still excellent sounding London original

The Speakers Corner pressing is very similar tonally to my original, and it took a bit of attentive care to pick out significant differences. With critical listening it is apparent that the SC pressing is more veiled in both transient attack, and in air/space around the performers. It’s not a bad pressing by any means, and gets very close to the original. That compromise could indeed be a very good deal when hunting the expensive 50s and 60s tube Deccas that command 3 figures or more. But fortunately originals of CS 6885 are relatively affordable, so for this comparison, the original is a no-brainer (and though the label differs, the London and Decca pressings are otherwise identical_ed.).

Now we get to the 45rpm main event: the Decca Pure Analogue press, remastered by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney C. Meyer from the original two-track master. The decision to cut this record at 45rpm is a bold one, it meant that the team valued the sound on this recording and took the extra time to put it on the best format it would fit comfortably on, and given the short run time of the piece, 45rpm works great here.

I wondered how, or even if, this new reissue could surpass my experience with the London original. But listening for the first time after playing the London, I was struck by just how tonally different this new cut is. From the opening wind solos I could tell Emil Berliner had really increased the transparency of this recording and now I was hearing a hyper-detailed stereo image. In many ways this was good because I heard greater micro and macro dynamics, greater texture, and once the piece got going, much stronger and deeper bass.

Yet at the same time some things were missing or less satisfying. For one thing, the hyper detail in the quiet sections showcased the kinds of sounds that distracted me from envisioning the orchestra on a stage in front of me. Things like key clicks, breathing, rustling of papers, all of those were up front in the stereo image and sounded almost disproportionately large in relation to the size and sound of the music.

There was also the issue of separation vs cohesion, and in many ways, while the soundstage on my London original was smaller in scope, it felt more like a unified “orchestral sound” than the Pure Analogue which cast such a wide stage that sections of the orchestra felt just a tad disjointed. The tone color also is changed, and certain aspects of that are improved with this new pressing, like the texture of the strings from the violins on down to the double basses which now have a grit and body that was only hinted at before. But on the other hand, reed instruments lose a bit of their richness and can approach an almost nasal quality that I never heard nor imagined coming from the Chicago Symphony woodwind section.

But then we get to the large and chaotic fortissimo sections of the ballet and where the original falls apart just a bit, the Pure Analogue picks up the slack, yielding some of the best clarity I have ever heard in complex and loud passages. This is a pressing that is remarkably sure-footed from the lowest level details up through the most stress inducing manic climaxes.

What you see in the paragraphs above are a weighing of the pros and cons of each of these excellent pressings and while this will satisfy almost no one, my subjective opinion is that neither cut is outright better overall, they are different flavors that will appeal to different types of listeners. If you want a warm presentation with an organic musical flow and sound design (one that I consider to be closer to the experience sitting in the audience) for this recording, get the original. However ,if you want the orchestra to be larger, with revealing textures and with a wider frequency extension featuring more noticeable high detail and deeper grunts from the bass instruments, this new Decca Pure Analogue really is a sonic marvel of transparency.

I spent a great many days listening to these different pressings and in all honesty, which one I liked better depended on my mood. The first time I played these back-to-back I swore that the original was the superior, more natural sounding version. However other days I realized I craved the window into the dense orchestral texture that the new 45rpm cut supplied. The reality is that they’re both excellent, showcasing how good the Decca engineering team at this time was, but they’re also both different enough that I think a strong case can be made for owning both.

To sum up a long scree on an important work of western art music, this piece should really be in every classical collection, large or small. And while there are plenty of options to choose from, very few hold the combination of a riveting performance and blockbuster sound that Solti and Chicago have captured with this recording. As long as this Decca Pure Analogue cut is in print, I think it should be an easy recommendation, especially if you don’t want to spend your time hunting for a clean original in dusty bins. If you happen to own an original that you love, this new cut might just surprise you as to what is hidden on these 50 year-old tapes.

.png)