Ahmad Jamal’s “Emerald” Treasures

Newly discovered live concerts from the ‘60s show the silky pianist was always an adventurer

Ahmad Jamal has long been known for his stately swing. He emerged as an innovative pianist, and a best-selling trio leader, in 1958, with his live album, "At the Pershing: But Not for Me". Even before then, Miles Davis touted him as a major influence on his own ballad style, citing his spacious phrasing and soft touch. Miles told his pianist of the era, Red Garland, to play like Jamal.

I confess I didn’t follow Jamal much between his lyrical late-‘50s breakthroughs (which I heard a couple decades later, when I started getting into jazz) and what I took to be a turn toward a more propulsive style in the late ‘90s (with The Essence, Part 1) and, edgier still, the early ‘00s (with In Search of Momentum). But some newly excavated live recordings from the mid-1960s tells me that I got this transformation wrong; the adventurousness was in him all along.

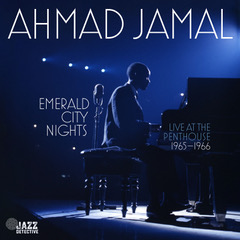

Zev Feldman, who unearthed many lost treasures for Resonance Records, has released this material on his new label, aptly named Jazz Detective. It amounts to seven sessions recorded at the Penthouse, a jazz club in Seattle , over a span of three years and a few months, selections (presumably highlights) of which are spread out across two 2-LP/2-CD sets, both titled Emerald City Nights: Live at The Penthouse, the first subtitled 1963-1964, the second 1965-1966. (The latter is somewhat better, musically and sonically, so that's what I'm reviewing here.)

Jamal still tickles the ivories with the spry delicacy that Miles emulated on his standards albums for Prestige. But he also pounds them, shifts from harp-like glissandos to percussive arpeggios without breaking a sweat or a seam. His sense of rhythm is almost infinitely elastic: he can shape space and time to whatever effect he desires, punctuating an eighth note or stretching a bar for whole lines, but always resolving the tension inside the melody. None of this is showy technique for its own sake. It’s all in service of where the song is going, and his sense of song are all about soul and wit and joy.

His bandmates are as in synch as any in the annals of jazz trios. The bassist, Jamil Nasser, supplies anchors and hooks of just the right weight and shape. His drummers, which vary from session to session, bolster or alter the beat, exciting or extending the rhythm, and keep the hi-hat cymbal going. In this sense, they’re working from the example set by Jamal’s drummer from the ‘50s sessions, Vernel Fournier, who rejoins the trio on two of the tracks here. (I would have liked to hear more tunes from that set.)

Finally, Jamal experiments with several standards that he’d played for years. He varies, speeds up, and slows down the meter on “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” as if commenting on the title; goes meditative on “Like Someone in Love”; and plays it straight, while the rhythm section does the familiar syncopation, on “Poinciana.”

Feldman told me that the sessions were recorded, originally for radio broadcasts, on ¼” tape Ampex 350 tape at 7.5 ips. Within those limitations, the sound is quite good, especially the bass, which sounds plucky, and the trap set, which is crisp. It’s mono, but there’s a real sense of ambience and depth. The piano sound varies a bit from one session to another, and it’s always a little receded. Still, Jamal’s technique, modulation, and romance come through clean.

It's a delayed instant classic.

.png)