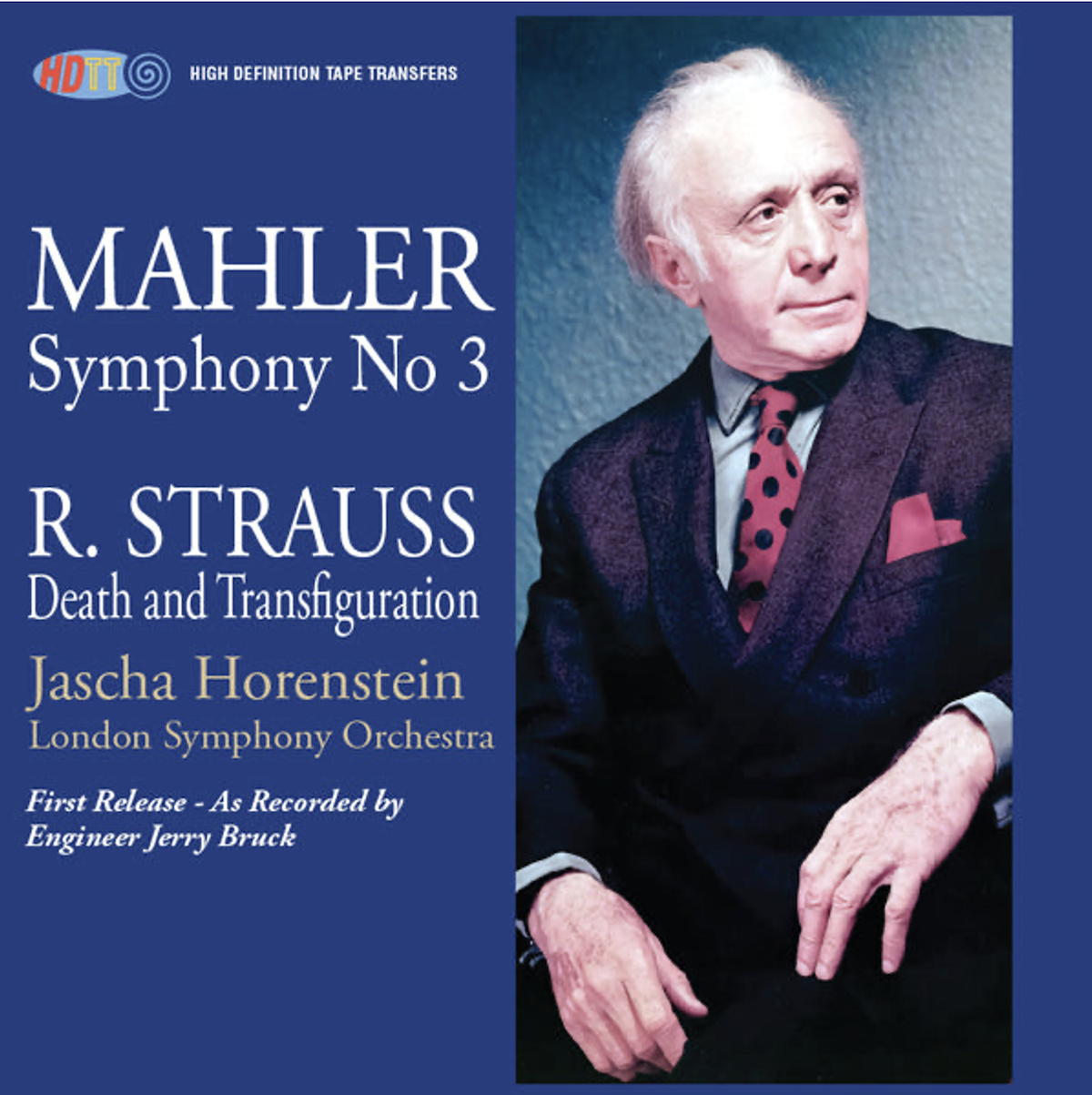

Jerry Bruck’s Legendary 1970 Jascha Horenstein/LSO Mahler Third Symphony Recording

An Epochal Performance, Properly Heard for the First Time

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 3 in D Minor

Richard Strauss: Death and Transfiguration

Jascha Horenstein, Conductor

London Symphony Orchestra

Norma Procter, Contralto

Ambrosian Singers, John McCarthy, Conductor

Wandsworth School Boys Choir, Russell Burgess, Conductor

William Lang, Flugelhorn solo

Dennis Wick, Trombone solo

John Georgiadis, Concertmaster and violin solo

First release of these performances as recorded by Jerry Bruck (a sample of which you can download free at the bottom of this piece).

Judy Collins’s 1975 LP album Judith was a favorite of mine. The first track on the first side was a memorably good cover of Jimmy Webb’s evergreen “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” so, what’s not to love? Being back then rather nuts about Baroque Pop in all of its various manifestations, I was charmed that the “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress” arrangement was for piano (credited to Collins), two flutes, viola, and horn.

However, my favorite track was Judy’s somewhat surprising, very Romanticized cover of the World War Two-era “weepie” “I’ll Be Seeing You” (words by Irving Kahal, music by Sammy Fain—but, with a big asterisk).

I say “World War Two-era” despite the fact that the song was written in 1938, three years before the United States entered WWII. In 1944, by which time very many people were acutely feeling the numbing pain of separation from loved ones, both Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby charted with covers of “I’ll Be Seeing You”—Sinatra’s reaching No. 4, and Crosby’s reaching No. 1.

Billie Holiday also released a version in 1944. Holiday’s recording of “I’ll Be Seeing You” was NASA’s final transmission to the Opportunity rover on Mars, before its mission ended in February, 2019. I find that poignant in the extreme.

As is the case with many “Story Songs” of that era, “I’ll Be Seeing You” starts with an introduction or a setup, often referred to as a “verse,” before the song launches into its main melody. “I’ll Be Seeing You”’s verse is:

Cathedral bells were tolling | and our hearts sang on;

Was it the spell of Paris or the April dawn?

Who knows if we shall meet again?

But when the morning chimes ring sweet again...

The sweepingly dramatic main melody is the setting for the (song-title) words:

I’ll be seeing you | in all the old familiar places

That this heart of mine

Embraces all day through

(The first word is usually strongly emphasized.)

Interestingly enough, Judy Collins sings the verse, and a very fine job she does of it. But Crosby, Sinatra, and Holiday all omitted the verse. That might be blamed upon the three-minute running time of a 78rpm side. However, Sinatra’s version, as an example, devotes its first 61 seconds to a “wedding cake” of an instrumental introduction. (Meaning, layer upon layer, and with decoration.)

My guess is that the producers believed that their audiences would rather hear familiar-sounding Big Band music, than scene-setting words. It is also likely that the producers wanted the singing to start with what Edward Elgar would have called “the big tune.”

Now, let’s get back to “I’ll Be Seeing You”’s sweepingly dramatic main melody. In Copyright litigation, the issue is sometimes raised whether a copyright infringement was unintentional. But the relevance is almost always only to the question of punitive damages.

As the presiding judge wrote in the most famous music-copyright litigation decision of modern times, that being the “He’s So Fine” infringement case against George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord”:

This is, under the law, infringement of copyright,

and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.

Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 420 F. Supp. 177 (SDNY 1976).

As you might have already guessed, there seems to be little question that the main tune of “I’ll Be Seeing You” is hauntingly similar to the melody that begins at about 43 seconds into the sixth and final movement of Gustav Mahler’s Third Symphony.

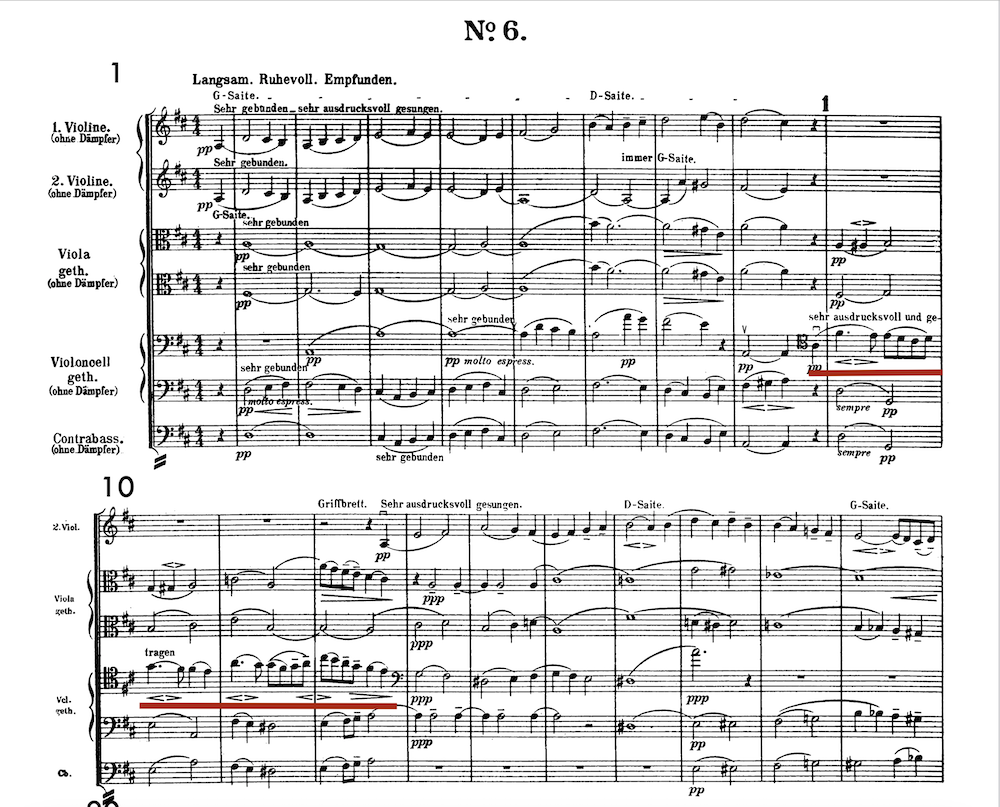

The orchestral cellos are divided into two sub-sections. The “I’ll Be Seeing You” theme appears in the music for the first cellos, underscored in red:

Note well, this theme recurs several times within the final movement; at times as shown above, and at other times slowed down or somehow varied.

Unlike the case with Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself,” where Carmen’s borrowing from Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto was obvious from the get-go, the resemblance between “I’ll Be Seeing You” and Mahler’s Third Symphony apparently was not publicly noted until 1970, when Mahler scholar Deryck Cooke mentioned it in a radio broadcast. But once it is pointed out, it’s hard to imagine that Mahler’s tune was not at least subconsciously embedded in Sammy Fain’s popular song.

Gustav Mahler’s six-movement Third Symphony (1893-1896; first performed 1902) is usually thought of as the longest symphony in the standard orchestral repertory. A performance lasts between 95 and 110 minutes. Mahler’s ambitious plan was to encompass all of creation in one massive work. His Third Symphony is scored for orchestra with a female (alto) vocal soloist, a women’s choir, and a boys’ choir.

In the fourth movement, the alto soloist sings a setting from Nietzsche’s “Philosophical Novel” Also Sprach Zarathustra, the “Midnight Song.” The fifth movement is based on one of Mahler’s own Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn) songs, which are settings of texts from a collection of German folk poems gathered and published in the early 1800s.

While he was working on his Third Symphony, Mahler would leave the house bright and early. As he went out the front door, he would call back over his shoulder to his Trophy Wife Alma, “I’ll be seeing you!”

OK, perhaps I made that up.

While he was working on his Third Symphony, Mahler thought exclusively in programmatic terms. After all, if a new symphony is to encompass all of creation (years later—1907—in a conversation with Jean Sibelius, Mahler expressed the thought thusly: “A symphony must be like the world, it must embrace everything”), an organizational scheme might be helpful, if you want to avoid primordial chaos.

Mahler’s top-level programmatic scheme was that the massive first movement (at more than 30 minutes, longer than many, if not most, complete symphonies) would be Part One, and the remaining five movements would be Part Two.

Part One was originally called “Pan Awakes,” Pan being the capricious half-goat god of Greek mythology. Hence the movement’s electrifying opening, scored for percussion and a chorus of eight French Horns. (But this recording employs nine!) By the way, it seems that Mahler intended the programmatic titles only for his own organizational and/or inspirational purposes; the titles were not included when the score was published.

Part Two consists of:

II. “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me”

III. “What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me”

IV. “What Man Tells Me”

V. “What the Angels Tell Me”

VI. “What Love Tells Me”

The two constants in Mahler’s Third Symphony are contrast, and change. The Classical symphonic form of four inter-related movements, with the first movement structured in what is called “sonata form,” simply was not a good fit with Mahler’s comprehensive artistic vision and his sprawling sonic ambitions.

One might think that such unprecedented idiosyncrasy in symphonic composition would have been ignored, or been subject to “howls of derisive laughter.” But, in the event, the 1902 première of the Third Symphony was a smashing success, with Mahler being called back to the podium 12 times. A local newspaper reported that “the thunderous ovation lasted no less than fifteen minutes.”

My theory is that Mahler’s disinclination to follow academic symphonic form, thereby giving free rein to his desire to encompass all of creation, is what makes the symphony appear less lengthy than it really is. It seems shorter than it is because there is so much change, and so much contrast. Whereas, 95 to 110 minutes of cycling the same material around the Circle of Fifths in order to arrive at some semi-arbitrary final-destination key is sure to get old by the 40-minute mark. In my humble opinion.

Also not to be ignored is the fact that the Third Symphony’s sixth movement, as one contemporary critic remarked, was perhaps the most beautiful slow movement written since Beethoven. I am fairly certain that the fact that the “I’ll Be Seeing You” Big Tune was still ringing in their ears, is why the audience stood and clapped for 15 minutes.

So now, let me tell you why High Definition Tape Transfer’s stunning first-release downloads, based upon Jerry Bruck’s experimental session tapes from more than 50 years ago, is a “Must Buy” recommendation if you love the music of Gustav Mahler. (However, the same holds true, even if all you want is to hear your stereo system sounding as though it is worth all the money you have put into it!)

1) First of all, the years around 1970 were a veritable Golden Age of Mahler interpretation. Today, Jascha Horenstein is one of the most respected (or, the most respected) of that generation.

Gustav Mahler died, tragically young, in 1911. But some of those who knew him and worked with him lived past the mid-century mark. The most important of those was Bruno Walter (1876-1962), who was an effective conduit to Jascha Horenstein of the indisputably authentic Mahler interpretative tradition. From 1901, Walter was Mahler’s assistant at the Court Opera in Vienna. In 1910, Walter helped Mahler select and coach the solo singers for the première of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony. At Mahler’s death, Walter was at his bedside.

Mahler did not live to conduct either his orchestral song cycle Das Lied von der Erde or his Ninth Symphony, but Mahler’s widow Alma asked Bruno Walter to conduct both premières. Decades later, mere months before the Nazi Anschluss forced him into exile (1938), Walter made the first commercial recording of the Ninth Symphony, a live recording of the Vienna Philharmonic, at a time when Mahler’s brother-in-law Arnold Rosé was still the orchestra’s Concertmaster. In 1936, Walter had similarly made the first-ever commercial recording of Das Lied von der Erde.

When Horenstein was in Vienna, Bruno Walter was conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, and Horenstein was strongly influenced by Walter’s conducting. Horenstein was also strongly influenced by Mahler’s “disciple” and colleague, the Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg.

Jascha Horenstein’s father Abraham haCohen Horenstein was Russian. His mother Marie Ettinger came from a well-to-do Austrian family. Her family tree included a famous Rabbi, Mordekhai Ze’ev Ettinger. Jascha (his legal name might have been Jakob) Horenstein was born in 1898 in Kiev, which was then a part of the Russian Empire. He died in London in 1973. His musical talents were recognized early on. According to Jascha Horenstein’s cousin Misha Horenstein, as a child, Jascha received his first piano lessons from his mother.

The flaring up of anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire from 1903 on, which reached a new level of intensity in 1905, caused Horenstein’s family to relocate from Kiev. First, to Königsberg, in Prussia, in 1906; and then to Vienna, in 1911. In Königsberg, Jascha began violin lessons with Max Brode. Later in Vienna, Jascha supplemented his income by playing in the second violins of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (not to be confused with the Vienna Philharmonic).

Jascha studied at the Vienna Academy of Music starting in 1916. He studied Music Theory with Joseph Marx, and Composition with Franz Schreker. Moving to Berlin in 1920, he became an assistant to Wilhelm Furtwängler, conducting the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

The Nazi Nuremberg Laws of 1933 put an end to Horenstein’s career in Austria and Germany. He moved to the United States, but never was able to obtain a permanent position conducting a top-ranked American orchestra. An early and fervent proponent of the music of Gustav Mahler, Horenstein conducted the 1952 Vox recording of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, the first-ever studio recording, and only the second commercial recording of that work.

Fortunately, the London Symphony Orchestra’s management offered Horenstein guest-conducting work. That eventually led to independent UK label Unicorn recording Horenstein with the London Symphony Orchestra, first in Mahler’s First Symphony in 1969, and then Mahler’s Third Symphony, in 1970.

Writing in the New York Times, famous classical-music critic Alex Ross stated:

Horenstein's authoritative interpretation of the Mahler Third is still available, and it is superior to all readings before and after. Horenstein's Mahler is free of exaggeration; he never bloats tempos in the manner of Klemperer or Bernstein. He is not afraid to let certain passages play out in an ordinary narrative mode, or to shape climactic moments with an unexpected sensual restraint. Mahler's music, already vehemently expressive at every turn, does not need to have its underlinings underlined.

(And, what an enviably lovely turn of phrase that last sentence contains!) Now, Alex Ross wrote that in 1994. But Ross’s criticisms of Klemperer and Bernstein are still valid, so I think his praise of Horenstein is also still valid.

And let it not be forgotten that fifty+ years ago, travel by jet aircraft was still mostly available only to the well-off, and telephone calls were still being made by Transatlantic cable. Which is to say that the state of “material culture and technology” back then worked to preserve the local or regional character of an orchestra’s style, in a way that was, not long after, lost.

2) Jerry Bruck’s “Experimental” Surround-Sound recordings are altogether superior to Unicorn’s tapes (which were also multichannel/surround).

Jerry Bruck

Jerry Bruck

Jerry Bruck is, as far as I know, unique among recording engineers, in that over and above his engineering achievements (such as having been appointed a Fellow of the Audio Engineering Society), Jerry made at least two massive contributions to the treasury of musicological learning on Mahler.

First, Jerry was one of the three American Mahlerites who persuaded Mahler’s widow Alma to rescind her previous ban on public performances of completions (largely in terms of the orchestration of the existing short-stave scores) of Mahler’s unfinished Tenth Symphony.

Secondly, after research carried on over the course of 30 years, Jerry’s monograph on the proper order of the inner movements of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony compelled the publisher of the Urtext edition to issue a corrected score.

With that degree of dedication, it should not surprise that, in 1970, Jerry Bruck would pack up everything needed for an experimental surround-sound recording session (except the tape recorders) and travel to London to record a Mahler symphony at his own expense.

Jerry’s “Tetrahedral Ambiophonic” recording method is a sublime marvel of engineering elegance and economy. Please read that sentence again, because I firmly believe every word of it.

Jerry positioned four (Schoeps) hypercardioid microphones at the apexes of a regular tetrahedron (a solid with three triangular sides and a triangular base, all identical), one meter on edge. I readily acknowledge that visualizing that in 3D will not come instinctively to many of us.

Therefore, I think that the easiest way to envision Jerry’s setup is to imagine an equilateral triangle made out of suitable dowels or metal rods, lying flat on a table, with one 60-degree-angled corner pointing straight back at you.

Across from (or opposite to) that corner, is the base of the triangle. At both ends of the triangle’s base, imagine microphone clamps and microphones, one microphone per corner. Those are the Left Front and Right Front (Stereo) microphones. The corner that is pointing straight at you holds the (monophonic) Rear microphone. Three down, one to go.

Now imagine three additional dowels or rods, one attached at each corner of the flat triangle on the table, of lengths equal to the flat triangle’s edges. These dowels or rods meet together over the center of the flat triangle, to make it three-dimensional. There is where Jerry placed his “Up” microphone, pointing straight up.

That’s right, and I am not making this up: Jerry’s “experimental” surround-sound system included an “Up” channel that was meant to be played back through a ceiling loudspeaker over the listening position. (Although, archival restoration engineer John Haley reports that Jerry’s two rear channels work just fine in the same plane, in a conventional 4.0 multichannel setup.)

It’s a real pity that Jerry’s “Tetrahedral Ambiophonic” work anticipated Dolby Atmos’s key feature (the “Height” channel(s)) by more than 40 years. 1970 was long before “ordinary people” would even momentarily consider the idea of affixing a hi-fi loudspeaker to the ceiling of their listening room. And, at the end of the day, today it’s mostly the Home Theater fanatics, but very few music lovers, who care anything at all about Height channels.

The truly elegant part of Jerry’s invention is that each microphone’s “nulls” were located in 3D space precisely where the other microphones perfectly filled in. Wow. The theoretical “listening position” for the soundfield is at the 3D center of the tetrahedron. And, right there, you have the true distinguishing characteristic of Jerry’s design—absolute respect for phase coherence.

Unicorn’s engineering team for Horenstein’s Mahler Third recorded to eight tracks of one-inch analog tape. Two of those channels were “ambiance” channels picked up by microphones positioned in the rear corners of the hall. Sorry, I don’t think that there is any way that that setup could preserve phase coherence.

Fairfield Hall's concert hall

Fairfield Hall's concert hall

Looking at a photo of Fairfield Halls’ concert hall (albeit in 2011), if Unicorn’s rear ambiance mics had been placed in the corners at either end of the first lateral or crosswise aisle (arrows), behind the first large section of floor seats, that’s at least 60 feet from the front of the stage. That’s about 52 milliseconds of delay. (I can’t imagine their setting up the ambiance microphones at the very rear of the hall, under the balcony overhang, but anything is possible, I guess.)

Jerry’s design is inherently superior, because his “Rear” and “Up” channels pick up the reflections from the rear wall and the ceiling as they would be heard at the listening position in a concert hall during a concert.

In his contribution to HDTT’s liner notes, John Haley states:

The effect of hearing all four channels is not to swamp the music in reverb but rather to add another dimension of clarity and realism, an effect that is clearly perceived when the rear channels are suddenly muted. The locational cues are of course still provided entirely by the front channels, as the direct sounds captured in those channels arrive to the listener first.

The unstated predicate to that paragraph is that the listener has to hear all four channels played back in a proper setup, which, as the liner notes also mention, can be a conventional 4.0-channel setup with the rear speakers in the same plane as the front speakers (rather than ceiling-mounted rears, as is the case in many Home Theater audio systems).

I should also mention that although the temptation to add a small amount of the content of Jerry’s “Rear” and “Up” tracks to the main stereo channels is obvious, John Haley tells me that, upon experimentation, the impact was detrimental, because of cancellation effects and the resulting lack of clarity. Therefore, the Stereo 2.0 downloads do not contain any sound from the “Rear” and “Up” channels.

Over and above the issue of the location of Unicorn’s rear ambiance mics, I have at least one other beef with Unicorn’s recording setup. While of course, at the same time, I acknowledge that, in 1970, Unicorn’s technical choices appeared to them to be state-of-the-art. As in, reportedly, the Unicorn recording of Jascha Horenstein’s 1970 Mahler Third Symphony was the first-ever multi-mic’ed recording recorded to 1-inch tape using Dolby’s Type “A” noise reduction.

John’s Additional Beef:

Unicorn recorded to eight tracks, on 1-inch tape. That said, contemporary reports strongly suggest that, as certainly was the case with London’s “Phase 4” recording setup (20 microphones into four tape tracks), more than eight microphones were in use. That is to say, in some cases more than one microphone per track was mixed down to create those eight tape tracks. Unicorn’s tape tracks were allocated thusly:

• Two tape tracks for the rear-corner ambient pickups (one for each rear corner);

• Four tape tracks for the orchestra;

• One tape track for the alto soloist; and

• One tape track for the two choirs.

But those are the tape tracks; that is not the actual count of the microphones.

I’d hazard a guess that each orchestral section was covered by at least two microphones, and that each choir (women, and boys) was covered by at least two microphones. My guess is that there were at least 15 microphones.

Engineer Bob Auger wrote technical notes for the recording’s first release as a 2-LP boxed set. Auger himself wrote, “In view of the large numbers of microphones used on the sessions to capture the precise details of the score… .” That might suggest that there were more than 15 microphones.

The irony being that, like his mentor Furtwängler, Horenstein cared less about the “precise details” of the score than he did about the meaning of the music:

“I learned from him the importance of searching for the meaning of the music rather than being concerned with just the music itself--to emphasize the metaphysical side of a work rather than its empirical one.”

I think that abandoning the simplicity of a “Decca Tree”-type mic setup in favor of “large numbers” of microphones was a case of going down the wrong road, and too fast.

3) HDTT’s digital transfers of the original Jerry Bruck at-session, in-machine analog tapes from 1970 define the “State of the Art” for 2024!

High Definition Tape Transfer’s proprietor Bob Witrak is obviously someone who has no patience with half measures or cut corners. The signal chain for this meticulous transfer from 1970 analog tape to 21st-Century high-resolution digital files (hmmm… suddenly, I am hearing a King Crimson song in my head!) would be very hard to improve upon:

Analog Source: Tapes played back on an Otari 4-channel professional 1/2" tape deck, as modified by JRF Magnetics in order to take the signal directly off the tape head, bypassing the Otari playback electronics;

Tape Playback Electronics: two (stereo) Merrill Audio Tape-Head Preamplifiers;

Digital Conversion: Merging Technologies S.A. (Puidoux, Switzerland) Hapi Analog-to-Digital Converter, clocked by an Antelope Audio 10MX Rubidium Atomic Clock;

Power Conditioning: Shunyata Research Everest 8000 for analog components; Shunyata Research Triton and Typhon for digital components.

One well might wonder what new State-of-the-Art transfers of Unicorn’s original in-machine, at-session tapes might sound like. I regret to report, it appears that Unicorn’s original in-machine, at-session 1-inch edited 8-channel tapes have been irretrievably lost, and for some time.

I have been unable to ascertain what the sources have been for the various CD releases of the 1970 Unicorn Horenstein Mahler 3, but one obvious possibility is the stereo copy tapes that Unicorn would have sent to Nonesuch in the US, so that Nonesuch could press LPs in the USA.

Another small point: Both Unicorn’s house engineers and Jerry Bruck recorded using Dolby type “A” noise reduction, which I have long regarded as a mixed blessing. Just like the case with dbx noise reduction, the key problem today is trying to find a hardware playback unit that has not gone flurky. Therefore, I was relieved to be told that HDTT’s Dolby type A decoding was accomplished by software, in the digital domain.

Summing Up:

After my first listen, I dashed off an email:

I listened to Jerry’s complete Mahler 3 last night, and here are my quick, brief reactions:

1) It sounds like it was recorded yesterday. It simply does not sound like a late 1960s, early 1970s commercial recording.

2) It’s hard to believe that it was recorded with only four mics--it sounds close-mic'ed, at least in terms of detail.

3) Anyone who says analog tape can't do dynamics must hear this recording.

Note, I listened to the Stereo version in its native resolution of 24/192. (The 4.0 tracks as well have a native resolution of 24/192.) Both the Stereo and 4.0 versions are also available in 24/96 PCM, and DSD64 and DSD128. The Stereo version is currently in press as a 2-CD set, delivery expected within about a week. Both the 2-CD set and all the downloads also have a wonderful Richard Strauss Death and Transfiguration, again with Horenstein and the LSO, recorded in the same sessions as the Mahler.

The Last Word:

As I mentioned way up top, High Definition Tape Transfers offers a free sample download of almost the first five minutes of the first movement, in 24/96 resolution. Which is generous, because I think that the first minute or so makes the sale. Just download it! (the sample download is towards the bottom of the page).

# # #

John Marks is a multidisciplinary generalist and a lifelong audio hobbyist. He was educated at Brown University and Vanderbilt Law School. He has worked as a music educator, recording engineer, classical-music record producer and label executive, and as a music and audio-equipment journalist. He was a columnist for The Absolute Sound, and also for Stereophile magazine. His consulting clients have included the University of the South (Sewanee, TN), Grace Design, and Steinway & Sons.

Note, High Definition Tape Transfers has released higher-than-CD-Quality downloads of Jerry Bruck’s JMR recordings of Nathaniel Rosen’s Bach solo-cello Suites. John Marks attests that that (minimal) commercial relationship influenced his evaluation of HDTT’s Jerry Bruck Horenstein Mahler Third downloads not in the least.

.png)