Lee Atwater's "Red Hot & Blue" Gave Me A Bad Case of the Jimjams

I tried not hating Lee Atwater's blues travesty "Red Hot & Blue," then realized the record hates me

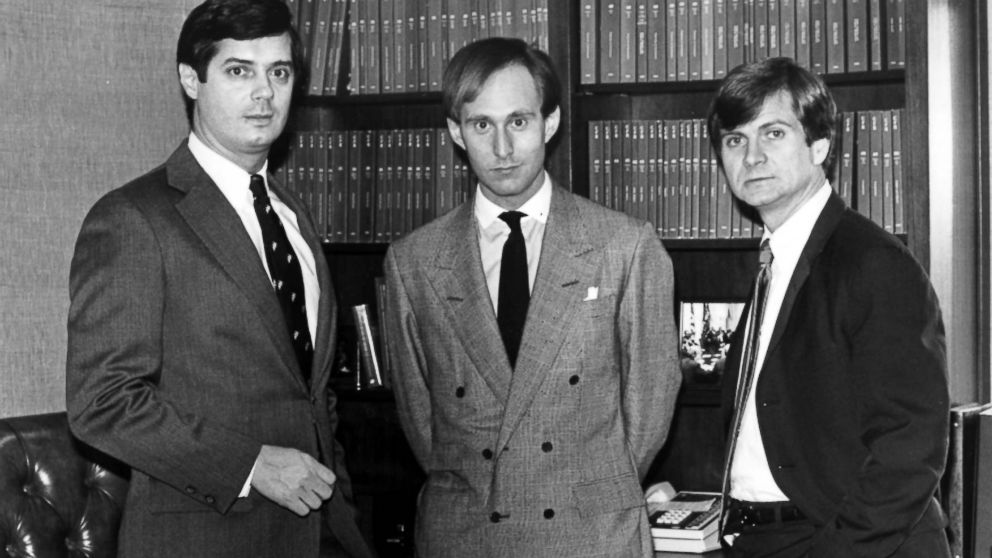

I carefully avoid hating bad music, as hatred poisons your soul and maybe your capacity to enjoy music. For that reason, I hesitate to say I hate Lee Atwater's vanity record "Red Hot & Blue," even though I know this disc hates me with painful readiness: its tacky, dated production makes my eyebrows tremble, Atwater's singing crimps the veins in my eyeballs, and his careful guitar playing gives me the jimjams, but more on that in a moment. The bad vibes began the moment Michael Fremer suggested I review the only record by the goofball on the right:

I don't know how Fremer got a sealed copy of this record by Lee Atwater, one of the most mean-spirited operatives in the history of politics, but I'm guessing Michael received it on the crossroads some time in 1990, along with a demonic pledge to bring back the vinyl record. (I will not divulge my source. However, I chose Mr Smith to review it because of geography and job description more than anything else. When I saw who plays on the record initiated by the creator of the "Southern Strategy" I was mouth agape seeing who was willing to join the band and wondered why. It's too bad few if any are alive today to talk about it, but I thought it was an interesting "piece of vinyls" to bring to your attention, if only for the novelty of it_ed.)

I don't know how Fremer got a sealed copy of this record by Lee Atwater, one of the most mean-spirited operatives in the history of politics, but I'm guessing Michael received it on the crossroads some time in 1990, along with a demonic pledge to bring back the vinyl record. (I will not divulge my source. However, I chose Mr Smith to review it because of geography and job description more than anything else. When I saw who plays on the record initiated by the creator of the "Southern Strategy" I was mouth agape seeing who was willing to join the band and wondered why. It's too bad few if any are alive today to talk about it, but I thought it was an interesting "piece of vinyls" to bring to your attention, if only for the novelty of it_ed.)

A Lee Atwater record! I feared that if I listened to it, my ensuing hatred would paralyze a core part of me, transforming me into the kind of person who brags about hating the Beatles. The below clip, full of Atwater's careless use of ugly racist insults, only begins to describe the awfulness of a figure who brought to this world a record as irritating as "Red Hot & Blue":

Much of Atwater's music is as wrong-headed as his political philosophy, particularly the first song on the album. Remember that old episode of Mad Men, "My Old Kentucky Home," in which Roger Sterling performed in black face? The musical equivalent is Lee Atwater's rendition of Slim Harpo's "Ti-Ni-Nee-Ni-Nu," in which Atwater's chalky voice proclaims that he is "Your Eechee Geechee Guy," the term "geechee" referring to the Gullah people, the descendants of slaves who worked the cotton, indigo, and rice plantations in the South Carolina low country. Lee Atwater did grow up and attend high school and college in the South Carolina low country, but he was about as close to the Gullah people as Alex Murdaugh was. Below is a YouTube clip of Lee Atwater's rendition of "Ti-Ni-Nee-Ni-Nu," but I discourage anyone who lacks a strong support system from listening to it.

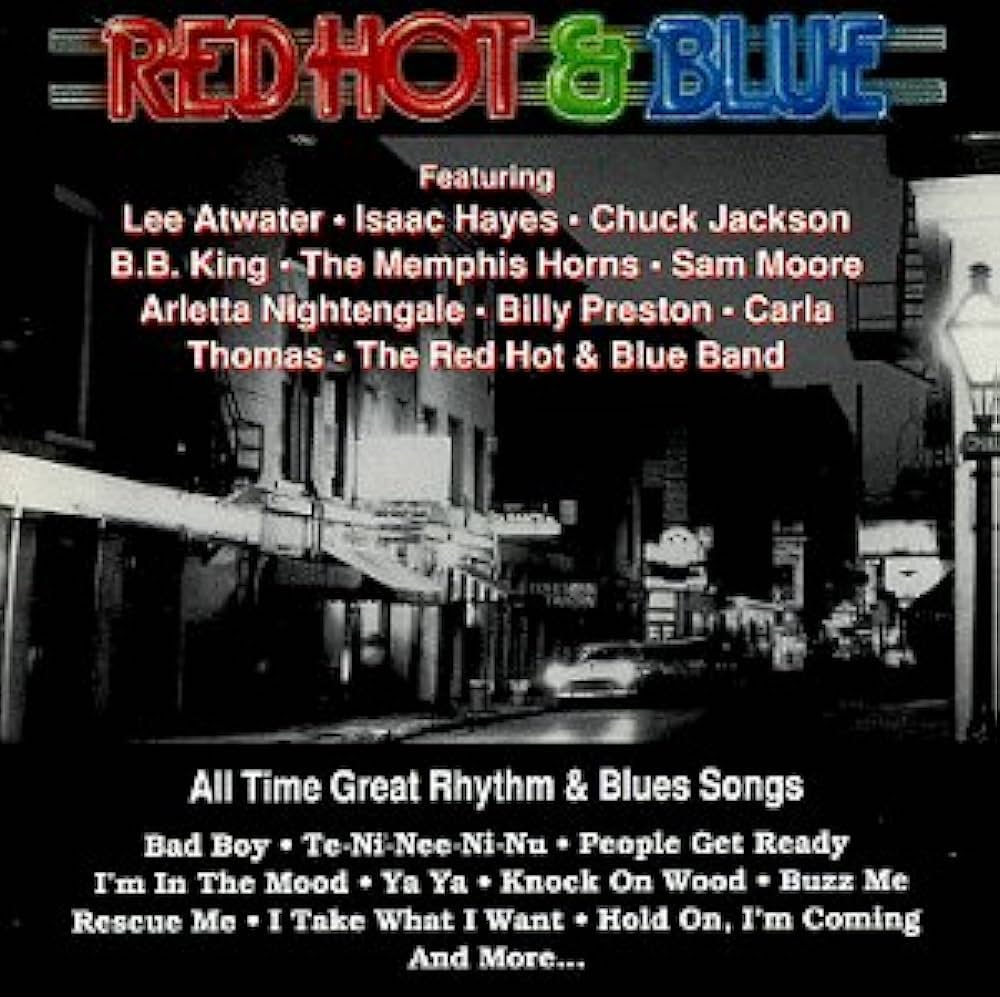

Earlier I said that Lee Atwater's guitar playing gave me the jimjams. I entered this jittery anxious state on my third listen of "I Take What I Want," when I realized I actually liked what Atwater was playing, or at least appreciated it--unlike so much '80s guitar, Atwater is not mimicking the maniac, I-just-escaped-from-prison guitar frenzy of Eddie Van Halen, nor does he try to approximate the thick tone of Stevie Ray Vaughn's playing. Instead, in the coda to "I Take What I Want," Atwater displays a style of spare minimalism, presenting the beauty of playing very few notes. I wish this appreciation was more long-lasting, but it vanished during Atwater's guitar duel with B.B. King in the title track, "Red Hot & Blue," in which Atwater's guitar sounded anemic, even sickly, compared to the purity of each note King cast from Lucille, his legendary Gibson hollow-body guitar. I felt the same way about Atwater's hoarse-voiced singing, but at least Atwater on most tracks hands the microphone over to his many guests, including Billy Preston, the aforementioned B.B. King, Isaac Hayes (who helped produce the record), Sam Moore (of Sam & Dave), Carla Thomas, and others.

Of course, this begs the question, who was Lee Atwater and how did he manage to get such legends as B.B. King and Isaac Hayes to play on his record? Well, for one, he was probably the most successful political consultant and campaign manager of the 1980s. One of Atwater's earliest victories was helping Karl Rove win a sharply-contested election for chairman of the College Republicans. He worked for South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond. After helping Ronald Reagan achieve the most lop-sided victory since Washington ran for president, Atwater became a senior partner in the same firm which gave us Roger Stone and Paul Manafort, Donald Trump's former campaign manager.

In 1988 Atwater helped the first George Bush become president, partly by orchestrating the cynical and racist "Willie" Horton ad, which blamed Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis for a Massachusetts policy permitting inmates to receive week-end furloughs-- Horton was out on furlough when he committed a rape and armed robbery in Maryland. (I put "Willie" in quotation marks because although Bush repeatedly referred to Horton as "Willie," Horton never used this nick-name and instead referred to himself as "William.")

Atwater met B.B. King and Isaac Hayes during the inauguration events for the first President Bush, and both recognized Atwater's genuine musical appreciation. But I think (and this is pure speculation on my part), that it was tragedy, and the bottomless empathy of Isaac Hayes, Billy Preston, B.B. King, and Carla Thomas, which brought these artists together to assist Atwater's dream of making a blues record.

I say tragedy because on March 5, 1990, Lee Atwater collapsed on stage while fundraising for then Texas Senator Phil Gramm. The father of three children, the 39-year-old Atwater was found to be suffering from a grade 3 astrocytoma in his right parietal lobe. He spent the final year of his life receiving aggressive cancer treatment, writing his memoirs, and exploring various religious faiths, ultimately converting to Catholicism before dying at age 40. Atwater also found time to record Red Hot & Blue, a testament to the medicinal properties of songs like "Rescue Me," and "Hold On, I'm Coming." If you are the social chair of your local chapter of the Federalist Society, and planning a mixer for first-year law students, or a member of the College Republicans curious about the Chicago Blues and Motown, Red Hot & Blue is a good record for you. Everybody else would do better buying records from Buddy Guy (Hoodoo Man Blues with Junior Wells, Left My Blues in San Francisco) or R.L. Burnside (A Ass Pocket of Whiskey) or early records from the Yardbirds and Rolling Stones.

The same year he was working on Red Hot & Blue, Atwater published an essay in Life magazine, in which he apologized for the ruthless and vicious way he had practiced politics: "In 1988, fighting Dukakis, I said that I 'would strip the bark off the little bastard' and 'make Willie Horton his running mate.' I am sorry for both statements: the first for its naked cruelty, the second because it makes me sound racist, when I am not." He added that he had found peace in his new-found faith, and that for the first time in his life, he no longer hated anyone.

Upon hearing of Atwater's death, B.B. King said, "I felt as if I lost a son when Stevie Ray Vaughn passed unexpectedly and I feel similarly on the passing of my friend Lee Atwater." Although I had originally given Red Hot & Blue very low numbers on Michael Fremer's Spinal Tap amplifier dial, I have revised the rating upwards to account for Atwater's late-in-life redemption and early death. To do otherwise would give me the blues, and possibly the jimjams too.

.png)