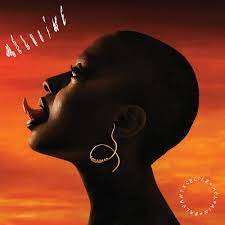

Cécile Salvant's Mélusine magic

The greatest jazz singer of our time expands her range to French Renaissance, cabaret, and much more

Cécile McLorin Salvant has reached the point in her career where she can, apparently, get away with doing whatever she wants. Dreams and Daggers and The Window solidified her status as the preeminent jazz singer of our time. Ghost Song, her debut on Nonesuch Records, cracked open all genres, covering a range enveloping Kurt Weill, Kate Bush, Harold Arlen, a 19th-century folk ballad, and a half-dozen original songs, which matched the album’s standards for wit, swing, and beauty—and it’s all of a piece, sequenced to tell a tale of love and loss, life and death.

Now, her follow-up, Mélusine, goes farther out there still. It’s unlike anything she’s done before—unlike anything anyone has done before, at least not on a major American record label.

First, the songs serve as commentary to a 14th century French folk tale about a woman who’s half snake (the half below her waist) and the revenge that she takes on a man who looks where he’d been told not to look. Second, the songs date as far back as the 12th century, though some are theatrical showtunes or vaudeville-era ditties, while others are written by Salvant (and, as with Ghost Song, it’s hard to tell which are which).

Finally (and this is where she takes a risk that, I suspect, few other labels would have allowed), she sings almost all of these songs in French. (The exceptions are one in Occitan, one in Kreyol, and one verse of another in English.) Salvant grew up in a bilingual household; she’s fluent in both and sings in a style that meshes early classical, jazz, popular, and cabaret.

Here's the main thing you need to know: This is a gorgeous album. Salvant’s voice is gorgeous—and wittier, more nuanced to the language than usual. (The booklet prints the original lyrics and English translations.) The arrangements, which she devised, are gorgeous, some with her usual jazz bandmates (pianists Sullivan Fortner or Aaron Diehl, bassist Paul Sikivie, drummer Kyle Poole), others with just a djembe percussionist or a nylon-stringer guitarist, all no more or less spare or lush than they need to be. And the songs are gorgeous—a mélange of modern ballads, melancholy dirges, spirited cabaret, Renaissance-style (Salvant studied classical singing, in France, before moving into jazz), some of her own composition, and, as with Ghost Song, all these disparate themes and elements somehow hang together, form a whole, a story—an album.

Savant originally recorded the album’s title tune (an original) for Ghost Song (that’s probably why she sings the first verse of that song, and no other, in English), but then decided to turn the themes of the Mélusine fairy tale into a separate album. She has long been attracted to songs and stories about “the destructive power of the gaze,” as she put it in Nonesuch’s press materials, and “the feeling of being a hybrid”—which she knows well, personally, having a white French mother and a black Haitian father. (A few years ago, she wrote and performed a much more elaborate piece on these themes, a 90-minute oratorio, with arrangements by Darcy James Argue, called Ogresse. It is a masterpiece—I’ve seen it live, twice—and will be an album, as well as an animated film, which she designed, sometime soon.)

Another treat about Mélusine: 10 of its 14 tracks were recorded in analog, and all of them were mixed in analog. John Davis of the Bunker Studio in Brooklyn laid down five tracks on 2” tape through a Studer A800, miking the set-up, in a single room (no headphones), mainly with Neumann microphones. Andy Taub recorded another five at Brooklyn Recording at 30ips on 2” tape, through a Studer 827. Salvant recorded three tracks—solos or duets with piano—in her home studio on digital. The title tune was recorded in digital by Todd Whitelock as part of the Ghost Song sessions (also an excellent-sounding album). Before mixing these disparate tracks, Davis transferred them to digital files, so he could edit them more easily and match their levels (“the biggest challenge,” he told me). Then he mixed them to ¼” analog tape, before his Bunker colleague, Alex DeTuck, mastered them for CD.

The result sounds as beautiful as you might suspect—vivid, rich, even lush, but all naturally so. Nonesuch plans to release a vinyl edition in May. We’ll write a brief follow-up when that reaches our hands. Meanwhile, this is vital to know about now.

.png)