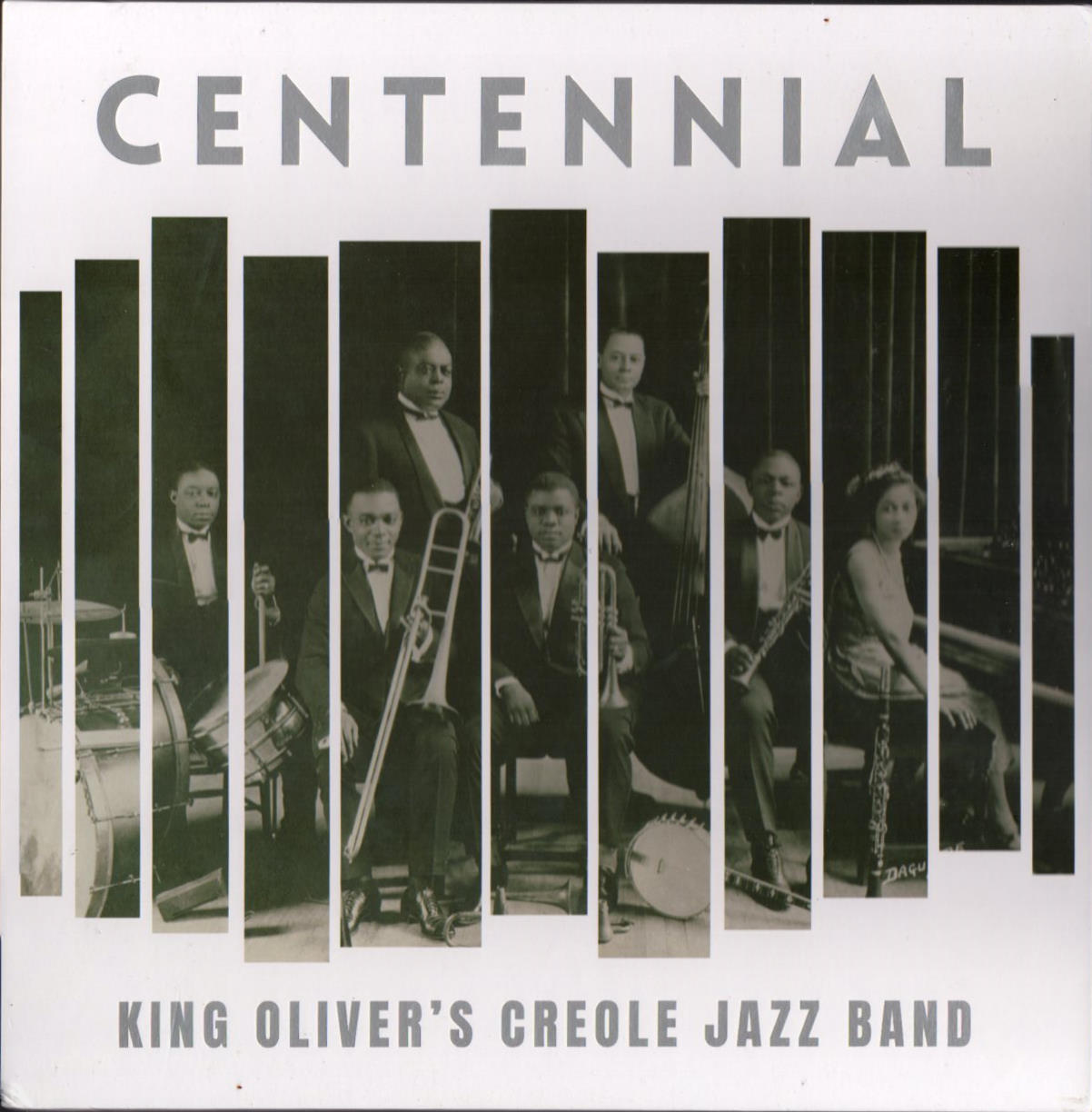

Centennial King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band

Deluxe Boxset Reissue of Historic Recordings

On April 5, 1923, in Richmond, Indiana, in the studio of Gennett Records, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band made the first of thirty-seven recordings mixing African instrumental techniques and concepts of improvisation and rhythm with European notions of harmony, melody, and the virtuoso soloist, to create the template for the music we’ve been listening to for the last century. The Creole Jazz Band’s six recording sessions, all between April and December in 1923, made for four different record companies, were the first extensive series of recordings by African American musicians that are indisputably jazz. They are also the first recordings of a working Black jazz band and the first of a band comprised primarily of Black New Orleans musicians. The recordings they made are the pinnacle of Black New Orleans traditional jazz and also the beginning of what would be called Swing music and, eventually, Modern Jazz.

Joe “King” Oliver (1881?-1938) was born in New Orleans and grew up in its unique musical culture. He was a great blues player and a master of the New Orleans polyphonic jazz style in which the horns collectively improvise over a strongly syncopated 2/4 rhythm. Oliver played within that tradition but was also an innovative musician and added solos, never before a feature of New Orleans jazz, to the music and lightened the rhythm, smoothing out the chopping 2/4 beat to create a new forward momentum groove. In addition to the standard New Orleans repertoire of blues, rag tunes, and turn of the century parlor ballads, he added pop tunes of the day but played them in Black jazz style.

In summer 1922, he was living in Chicago, leading his Creole Jazz Band, and playing a long successful gig at the Lincoln Gardens, a dance hall in a Black neighborhood. Tragically, he was suffering from a gum disease that would eventually end his music career, and it was beginning to affect his playing. Needing another cornet to bolster the band’s sound and lessen the load of playing four sets per night, he sent word to Louis Armstrong (1901-1971), his former student in New Orleans, offering him the job of second cornet.

Armstrong arrived in Chicago, July 8, 1922, a few days more than a month before his twenty-first birthday. Soon, it became apparent to Oliver that Armstrong was no longer his student but a brilliant musician who was changing the sound of the band. Armstrong and Oliver began working together, exploring uncharted territory. Traditionally, New Orleans jazz bands consisted of three horns: a cornet, a clarinet and a trombone, all playing independent but interlocking lines in their own registers. Two cornets in a band was an innovation that threatened to upset the intricate and graceful balance of the polyphonic improvisation at the heart of New Orleans jazz.

Oliver and Armstrong quickly developed a way to play lines together, but independently, that would diverge and merge, complementing each other. Arrangements had been rarely used in New Orleans jazz before but they developed “breaks” when the two cornets would play the same seemingly improvised line in unison and also worked out solos that were repeated every time they played a tune. Seemingly spontaneously but actually arranged, one would play lead while the other would improvise behind, then switch the lead, or they would improvise together while playing the melody. The complexity of the interplay between Armstrong and Oliver astonished other musicians and audiences at The Lincoln Gardens and made clear that jazz was not merely a raucous dance music.

Oliver was a very talented professional musician, but Armstrong, though in technical command, not yet the cornetist he was to become, was a paradigm changing genius and, even with his youthful limitations, was beginning to make jazz into a virtuosic, sophisticated music. His bright, powerful, clear cornet tone with dynamic, punching high notes was unlike any other player in 1923, but it soon became the way the instrument had to be played. He was blessed with a great ear for harmony, and much of his playing went well beyond the basic harmonic conventions of jazz at that time and pointed the way to the Swing Era. While other players were playing solos that were not real improvisations but only simple variations on the melodies, he played logical, singable lines based on the harmonies, which was to become the primary method of all jazz prior to the music of Ornette Coleman.

All innovation in jazz has been based on rhythm, and Armstrong’s time and rhythm feel were not just avant-garde but positively futuristic for 1923, and so strong that the other players, not ready yet to feel or hear or play the even four/four 1935 style swing rhythm he was hearing, were pushed by him into a rocking, wild, barely controlled groove that was a raw and pounding “proto-swing.” The loose but tight, in the pocket, furious rhythmic intensity of the Creole Jazz Band, powered by Armstrong, was soon to change popular music forever.

In August 1922, Gennet Records, upon the recommendation of a manager employed by the Starr Piano Company, which was another enterprise owned by the Gennett family, recorded a white New Orleans jazz group, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, and sold enough records to warrant calling them back to record again in late March 1923. The same manager had heard Oliver and the Creole Jazz Band play live and secured his place in history as a supreme talent scout and uber-hipster, by insisting that they be also recorded. Gennett agreed and took the unprecedented step, for a white owned record label, of recording a Black jazz band. Since the company was also pressing records for the Ku Klux Klan, we can assume that a commitment to racial equality was not a motivation.

On April 5 and 6, 1923, King Oliver, cornet, accompanied by Amstrong, second cornet, Johnny Dodds, clarinet, Honore Dutrey, trombone, Lil Hardin (soon to be Armstrong’s second wife), piano, Bill Johnson banjo and Baby Dodds, percussion, were in the primitive Gennett studio, before the recording horn and recorded nine tracks. All except Lil Hardin and Bill Johnson were born in New Orleans.

Johnny Dodds (1892-1940) was one of the greatest New Orleans clarinetists, possessed of a beautiful, very dark, bluesy tone. His brother Warren “Baby” (1898-1959) Dodds was a very talented drummer who, unfortunately, due to limitations of the Gennett recording equipment, was restricted to playing wood blocks and a cymbal. Lil Hardin (1898-1971) studied at Fisk University and was the only “schooled” musician in the band. She played hard driving, rhythmic piano and provided a solid harmonic basis for the horns. Honore Dutrey (1894-1935) was not a great improviser but a capable New Orleans jazz ensemble trombonist who provided a “no fancy, show-off stuff” bottom line for the other horns. Bill Johnson (1872-1972), the oldest member of the group, was a bass player and is believed to be the originator of pizzicato playing on that instrument in jazz. Bass did not record well on the acoustic horn technology of 1923, so at Gennett, he played banjo.

Gennett #5132, “Dippermouth Blues,” backed with “Weather Bird Rag,” the first of the records from the session, was released on May 8, 1923. This Creole Jazz Band version of “Dippermouth Blues” (later a Swing Era standard recorded by Benny Goodman and many others under the title “Sugarfoot Stomp”) is one of the classic recordings of American music. Probably mainly composed at the Lincoln Gardens by Armstrong (“Dippermouth” was his nickname), the tune begins with a diminished chord, considered avant-garde for jazz in 1923. The band comes in stomping hard, playing the blues theme over woodblocks while Oliver plays a strong lead. After two choruses, they go into stop time and Johnny Dodds plays a beautiful, melodic solo. After another chorus of the ensemble in which we hear Armstrong playing lead, Oliver, with a mute in his cornet, plays one of the greatest “solos” of early jazz (not exactly a “solo,” he is featured up front, but the other horns continue to play behind him.) For two choruses, he sings, shouts, and moans a continuous blues melody like a great singer while pushing hard against the beat. The third chorus begins with him moving up in register and digging in even harder, positively shouting to the finish. Bill Johnson yells out, “Oh play that thing!” and the band comes back rocking with Oliver playing the melody over some bluesy melodic fills from Johnny Dodds. Hearing the Creole Jazz Band play “Dippermouth Blues” live with people dancing and shouting and urging them on must have been an incredibly powerful and exciting physical and emotional experience. We have the testimony of many musicians that hearing the band changed their lives.

“Chimes Blues” coupled with “Froggie Moore” on Gennett #5135, was released on June 30, 1923, and features the first Louis Armstrong solo on record. The band plays the melody for two twelve bar choruses, with Johnny Dodds weaving melodic variations around Oliver’s strong lead before Lil Hardin plays “chimes piano” for two choruses. Then history happens, and Armstrong solos for twenty-four bars. It’s a real solo as he’s only accompanied by the rhythm section and not just variations on the melody but a real improvisatory musical statement that is logically structured around a three note rhythmic figure based on the “chimes” theme which he continually returns to throughout the solo and underlies all the melodic ideas he plays. Armstrong’s tone is big, powerful and dynamic and you can hear, even on the acoustic horn recording that he is playing loud. He ends his first chorus with a sudden upward rip, which might be the first one ever recorded. During the second chorus, he continues to play variations on the three note figure but looser, and his rhythmic intensity is greater, grooving, down deep solidly in the pocket, so strong that you can feel the beat even when he’s not stating it. The solo is not a masterpiece but foreshadows all the incredible masterpieces to come.

The first five Gennett records, especially “Dippermouth Blues”/”Weather Bird Rag,” sold well, and in the “That stuff is selling. We need some of it too,” way of the record business, many other Black jazz bands were quickly recorded. There were no exclusive contracts except for the biggest opera and pop stars, and King Oliver’s band was hot. Other record companies, trying to compete in the now suddenly profitable business of Black jazz, were eager to record the only band that had proven it could sell records. Offers were made and Oliver, who, as leader, was pocketing all or most of the fees, embarked on a busy recording schedule.

Okeh, one of the most successful companies, which had recorded Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” a huge hit, showing that Black people wanted to buy records by Black people and were a viable record market, recorded the band in June 1923. Okeh ran ads promoting the records in Black newspapers and were rewarded with strong sales.

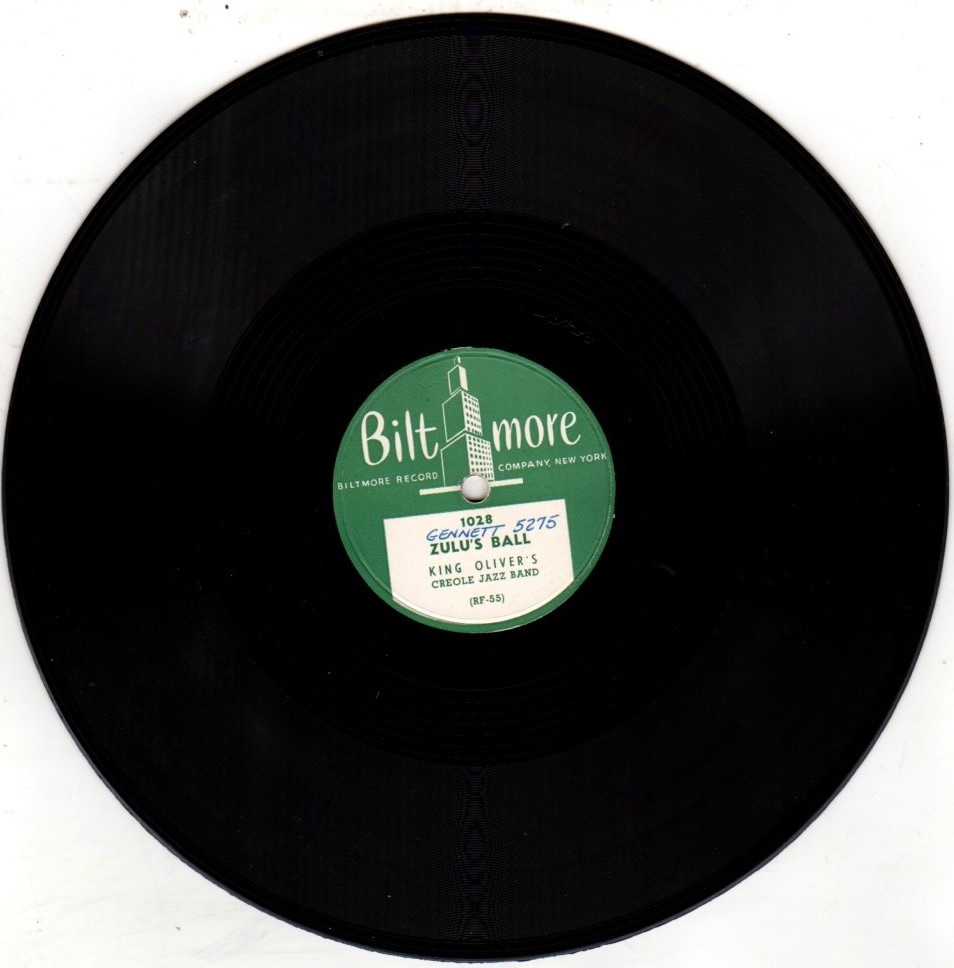

In early October, Gennett had the band back in the studio and though the music was good, sales of the two records released were disappointing or near non-existent. One, Gennett #5274 “Krooked Blues”/ “Alligator Hop” is a very rare record today. The other, Gennett #5275, “Zulus Ball”/”Workingman Blues” is one of the legendary rare records. Only one heavily played V copy ever has been found and that in 1944.

Okeh recorded the band again in October and Columbia, one of the major players in the industry and already in business for 34 years, decided it was time to jump on the Creole Jazz Band wagon and did as well. Oliver and the band finished out a busy year in the studio for the storied Paramount label on or about Christmas Eve.

These were the last recordings of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Sometime in late 1923 or early 1924, the band broke up. Reasons vary. Hurt pride might have been one of them. Baby Dodds said later that Oliver began to refer to the group as “my band” rather than, as formerly, “our band.” Reportedly, there were personal tensions between Oliver and Johnny Dodds. Then, of course, as always, there was money. Allegedly, Oliver refused to reveal the amounts of royalty checks to the others, and while the Lincoln Gardens was paying him $95/week each for the sidemen, he was giving them only $75 of it. It might have been just practical business—Oliver had a two to three month tour scheduled for early 1924, and only Armstrong and Hardin were willing to leave Chicago.

Whatever the reason for the breakup may have been, it was probably the right time. Armstrong’s innovations were making jazz a soloist music and New Orleans polyphonic jazz outmoded. His genius was too enormous to be confined in a New Orleans style ensemble. Out of respect for Oliver, he had tamped down his talents in the Creole Jazz Band so as not upset the delicate balance the music required, but he was pushing at the boundaries and was soon to burst free.

Approximately six months after he left Oliver’s band, Armstrong joined the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra in New York, probably the most successful Black big band at the time. On October 7, 1924, he recorded with them and on “Go Long, Mule,” an otherwise forgettable tune, he burst out of the ensemble’s stodgy two beat feel, to play a solo of such swinging intensity that there could be no doubt that the future of jazz had arrived and the possibilities were limitless.

The Creole Jazz Band records were regarded as classics by the earliest “jazz fans,” and in the late thirties and early forties, long out of print and even then, hard to find, were reissued on 78 rpm by bootleg labels. These were “dubs” copied from records, some from very worn copies, and most were barely listenable.

In the early 1950’s, there were ten inch microgroove reissues of varying degrees of dubious legality. One company even called itself “Jolly Roger.” Sound mastering on these was of the “turn the treble knob all the way down to hide the noise” style, and the sound ranged from bad to dreadful.

A Riverside LP of Creole Jazz Band sides was issued under Armstrong’s name in the later ‘50s and then reissued in the early ‘70s. The sound was muffled, distorted, and very bad.

The first reissue that presented the music in an organized fashion with good sound quality was the 1981 Herwin issue, The Great 1923 Gennetts. This LP was produced by legendary collector Bernard Klatzko, and mastering was by the equally legendary Nick Perls in his non-interventionist style. He used clean original Gennett 78s as source material (Zulu’s Ball/Workingman’s Blues excepted, of course). The LP sounds like near straight dubs of clean 78s with some midrange boost and a fairly steep rolloff at about 2000hz to moderate but not eliminate the surface noise. The record is an enjoyable listen.

In the CD era, after many issues seemingly dubbed from the Herwin album, the Riverside album, cassette copies of 78s or other poor sources, John R.T. Davies, who, it could be said without more than slight exaggeration, invented high quality 78 remastering, did the first high quality remaster of all the Creole Jazz band recordings, the Complete Set for the Retrieval label in 1995. His approach was decidedly more interventionist. Surface noise is noticeably less and smoothed into the background using noise reduction. Dynamic range is wider, possibly due to digital transferring. He also did extensive equalization to emphasize the horns and piano. The result sounds more “hi-fi” but less like the original 78s.

Archeophone’s 2006 Off The Record remastered by Doug Benson aimed to sound like ultra clean copies of the original 78s. Advances in de-clicking and de-noise programs made it possible to reduce surface noise to mostly an unobtrusive hiss well behind the music. Equalization was not used, so the music sounds less dynamic and “hi-fi” but better balanced and more cohesive. The first time I heard these CDs, I thought they lacked the excitement of the Davies remaster but I soon found the less accentuated top end and more natural sound easier to listen to for a whole CD.

In the liner notes to the Herwin LP, collector Dick Spottswood is quoted, “The Oliver Creole Band should be reissued every ten years as electronic equipment improves.” Well, it’s been eighteen years since the last truly new reissue, and Centennial is a year late, but Archeophone is back with a new deluxe, state of the art, reissue of the complete recordings of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band utilizing the latest technology.

The set includes a sturdy, attractive LP sized box with an 80 page hardcover book, a poster, two LPs in a gatefold cover which include all the 37 recordings of the Creole Jazz Band, and four CDs in another gatefold. Two of these are the Creole Jazz Band tracks. Another is entitled “Louis’ Record Collection,” a bit of a misnomer and consists of a miscellany of comedy, opera, military bands, jazz and pop that Armstrong listened to or might have. The fourth, “Joe’s Jazz Kingdom” is music of other bands on the scene recorded between 1920 and 1923. The book superbly reproduces label shots (both sides) of all the records, many photos of the band, some of which I had never seen and includes magisterial liner notes by Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Mr. Riccardi should be making shelf room for a Grammy award soon.

So, how does this version of the King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recordings sound? If I tell you that the 37 tracks sound fantastic and better than they ever have, what do I mean? Should you expect them to sound like Roy DuNann or Rudy Van Gelder recordings? The answer is emphatically, “No.” Some explanation is necessary.

All of these recordings were made using acoustic horn technology with little frequency response above 2000 hz and a severely limited dynamic range. No microphones or tape were used. The only electricity in the studio was for light bulbs. The musicians mixed themselves by adjusting their volume and proximity to the horn. Reportedly, Armstrong’s sound was so big and loud that he stood at the very back of the room approximately 30 feet away. A type of direct to disc process was used with the horn vibrating a cutting needle on a wax disc that was used to create a metal master.

It is known that Gennett destroyed three of their Oliver masters in 1929 and probably all the rest at the same time or soon after. The other companies destroyed all of theirs or donated them to the war effort in the scrap metal drives of World War 2.

Today, the only way to do a high quality reissue of the King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recordings is to dub from whatever issued 78 rpm records you own or can beg or borrow. The records are made from shellac, and even when in near new condition, play with surface noise. Finding a Creole Jazz Band record, let alone a N- condition copy “in the wild,” is all but impossible, and buying one from auctions, is very expensive. Even the “common” records like “Dippermouth” are rare and usually very worn.

Original Creole Jazz Band 78s play with a raw, wild, passionate immediacy that none of the reissues have captured, but require practiced and imaginative listening. Even the best reissues, while being less noisy and more “listenable,” have all sounded restrained, modest, and refined by comparison. Remastering the records for reissue has always been an attempt to find the cleanest copies available and then reduce the shellac noise, the wear noise, any distortion, and pops and clicks while preserving as much of the music intact as possible. Less noise = less music = less wildness has been the irrefutable equation.

The new Centennial remaster by Richard Martin sounds significantly better than any prior version of the King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recordings. According to the note “Restoring The Oliver Sides” in the Centennial book, “The most exciting development in restoration software over the last few years is spectrographically based repair tools. These allow for “healing” of problem areas by means of sophisticated interpolation algorithms and they also work well for targeted equalization.” The use of these tools has produced a fuller, wider sound with a beefed up and much fuller bottom end, which on these recordings is the lower midrange. Lil’s piano is significantly more audible, which makes the rhythm more solid and her important role in the band more obvious. The trombone lines can be heard more clearly, which adds to the complexity of the ensemble sound. There is more space between the horns, and they are more distinguishable in the ensembles, which is all important in this music. The band, as a whole, sounds warmer, less shrill, and more like a band. Most importantly, I hear more dance hall stomping wildness, more passion, than I have heard on any previous reissue of these recordings. We will not hear a reissue of this music sound better for a long time, if ever.

I expected the Centennial LPs to sound very much like the CDs, but they don’t. There is no specific information in the book about mastering of the LPs. Almost certainly, they were mastered from the same files as the CDs, but the surface noise heard on the CDs is noticeably quieter on the LPs, and overall, they are not as bright as the CDs. Dynamic range was less as well. The records were well pressed, without scratches, and did not add any significant noise. I preferred the sound of the CDs.

Hoagy Carmichael said of the music of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, “Something as unutterably stirring as that deserved to be heard by the world.” Unfortunately, the acoustic recording process and the quality of many of the reissues has served the music poorly, and it has not been as widely heard and appreciated as it should have been. Centennial is the most important reissue of traditional jazz in many years, a milestone and new benchmark for the remastering of acoustic era music, and hopefully, its beautiful, deluxe packaging and what should be great critical acclaim, will encourage more people to listen to some of the greatest music ever recorded in America.

NOTE: I rated the sound "10" because this is the best sounding reissue of these recordings. But the original recordings were made with primitive acoustic horn technology over 100 years ago and are not high fidelity recordings. I think my review makes clear the limitations of the recordings and source material.

Thank you to Richard Bowman of the Golden Mystics Of Old Time Music website for loan of the Off The Record CDs.

Copyright and all rights reserved 2024 by Joseph W. Washek

.png)