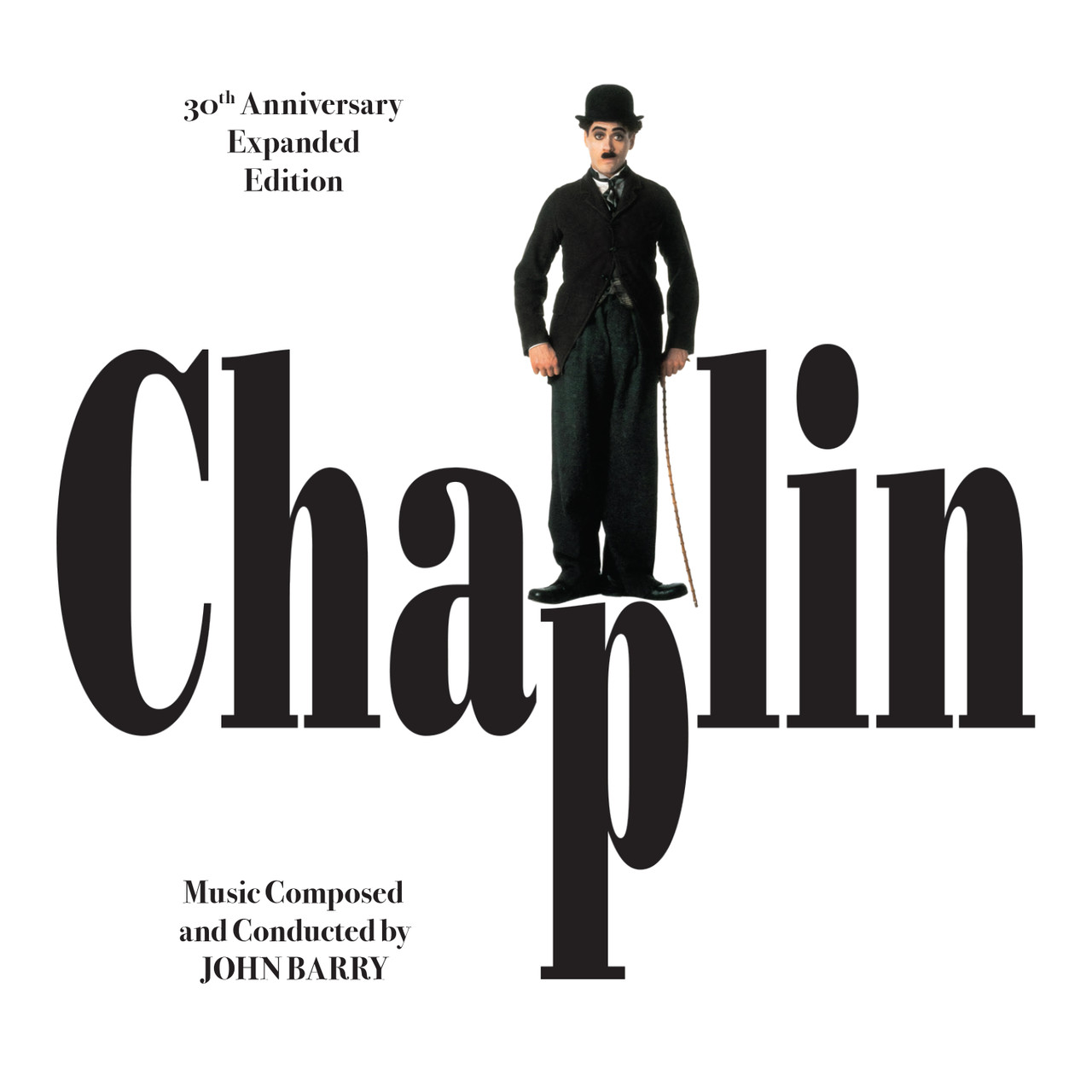

Chaplin - Original Soundtrack: 30th Anniversary Expanded Edition

John Barry's Late-Period Score Enchants in this Newly Remastered and Expanded Edition from La-La Land Records

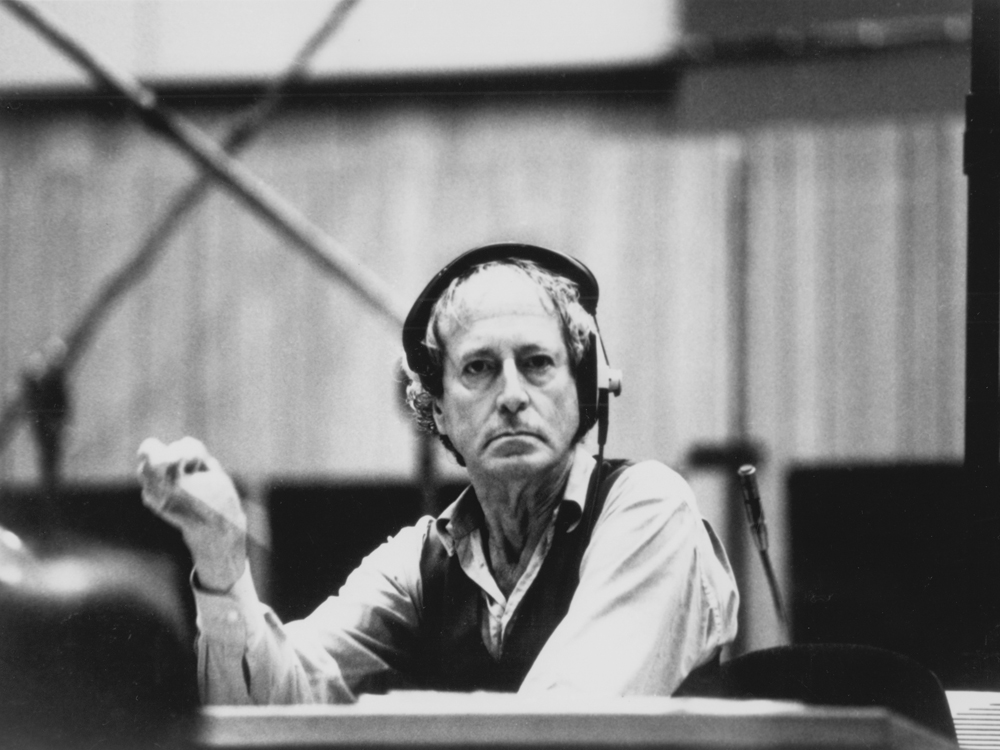

For anyone more familiar with John Barry’s 50s and 60s discography and his early scores for spy films like the James Bond series or The Ipcress File (1965), encountering his late-career work on films like Dances with Wolves (1990) and Chaplin (1992) can be a bit of surprise. Gone are the stylings of his era-defining London mod classics like “Hit and Miss” and “Beat for Beatniks”, let alone his genre-defining “James Bond Theme” (Barry's arrangement of a melody by Monty Norman). Instead, his dominant mode has become more overtly "classical", with brooding brass choirs set against lyrical strings, piquant winds, all drawn together by long-flowing melodies. Jazz and blues chords articulate a melancholy never too far from the surface. And everything has been slowed down - way down.

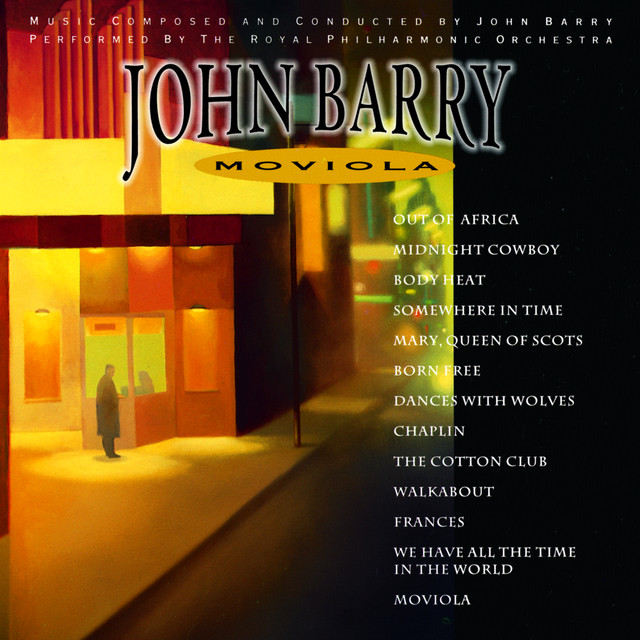

That this style had become predominant was borne out not only in his later scores, but in his newly recorded “John Barry” compilation albums. In 1992 Barry began this “re-imagining” of his catalogue with two albums of his classic themes with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, which sounded very different from his earlier “re-recorded” compilations from the 60s and 70s. These later albums were fully entrenched in the style described above. While the first album, titled Moviola (1992), featured themes that were already composed within, or close to, this idiom in the first place, the follow-up in 1995 - Moviola II: Action and Adventure - felt more like a shoe-horning together of two incompatible styles, and to these ears was less successful as a result. Barry’s later albums of all-original material like The Beyondness of Things (1998) and Eternal Echoes (2001) were as close as he would get to full-blown “classical” works, albeit broken up into shorter theme-based movements.

In fact, to anyone paying closer attention to Barry’s work from the beginning, this more “classical” style (for want of a better word to describe it) was never far from the surface. His first Oscars were won for Born Free (1966), whose lush themes and orchestral textures he revisited in another Oscar-winner set in Africa twenty years later, Out of Africa (1985). Scores for historical dramas like Mary, Queen of Scots (1970) and The Lion in Winter (1967) delighted in integrating classical elements (and even period-appropriate instruments) into the instantly recognizable John Barry-style. Once you dive into even his Bond scores you will realize this rich symphonic idiom was more prevalent than you remember. Think of all those cues in Bond with slow-moving brass set against strings and fluttering woodwind, like this one from Moonraker where Bond is lured through the jungle to the villain Drax’s lair by a bevy of beautiful women. Barry adds an extra note of musical seduction by including wordless women’s voices in the mix.

Moonraker - Bond Lured into Pyramids

Think also of Barry’s more lyrical theme songs like the glorious “You Only Live Twice” or the bittersweet ballad “We Have All the Time in the World” from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, one of Louis Armstrong’s last recordings (he was too ill to play the trumpet solo, re-allocated to a studio musician). Take away the rhythm section from the latter and you have a memorable, poignant melody and harmony that will break your heart, as it did when Hans Zimmer referenced it so effectively for his heavily Barry-infused score (and all the better for it) for No Time to Die (2021).

No Time to Die: Matera

That strain of melancholy which so deeply infused Barry’s music, and which became dominant in his later years, is to the fore in his exceptional score for Chaplin, Richard Attenborough’s increasingly highly-regarded biopic of the great filmmaker. We can now fully appreciate just what a fine piece of scoring this is thanks to yet another state-of-the-art reissue from La-La Land Records. This gathers together cues absent from the original CD soundtrack release (it was only ever issued on vinyl in Greece, Spain and Brazil, according to Discogs), in an excellent remastering and with the customary first-rate accompanying notes and photos.

One of the most fascinating aspects of film music is how it can change or amplify the intent of a scene, and sometimes color an entire movie, in a way that goes beyond what the director originally intended. This was definitely the case with the main theme for Chaplin, which sets the tone for the whole film. As recounted in the characteristically excellent notes by Jon Burlingame (Variety's film music critic), Barry caught the director by surprise when he first played him his music.

Burlingame writes:

Barry found his inspiration in the first few minutes of the film as Chaplin - dressed as The Little Tramp - returns to his dressing-room to remove the outer trappings of the character and unveil the human being behind the make-up.

“The Chaplin theme came from the footage that Richard shot for the opening title sequence,” Barry explained in the 1993 PBS Special Movieola. “The stick going down on the back of the chair, the hat, the mustache into the tin, and then slowly removing the face of the Tramp to reveal the real man.

“To me the sadness just came out. By the time you cut to his face at the end, when he throws down the towel, there was this extraordinary, solitary, sad man. And knowing the history of Chaplin’s life, that last image, I just thought, God, this is sad.”

Attenborough was, at first, skeptical. “I have to tell you that, when John first played the theme music that he wanted to use, I wasn’t necessarily convinced and I was totally surprised. I didn’t believe that he would be able to hold a melody of beauty and love, and yet invoke from it such a feeling of sad solitude. I think John has contributed an element to the movie beyond anybody’s preconception. He’s brought his own particular magic to lift the story onto another level.”

Scored for solo piano and strings (with subtle shadings of low alto flutes - a Barry favorite), this cue perfectly sets the scene for what is to follow.

Chaplin - Opening Credits

(This story is as good an example as any of why using temp scores - the practice of putting temporary music cues onto the rough edit of a film - is a terrible idea. The temp music becomes so familiar to the director, editor and producer that it makes it much harder for the composer to come in and offer up something different (and usually better). This is such a common practice nowadays that it's a principal reason why all film scores are increasingly sounding the same).

From that memorable opening, Chaplin tells its tale in a series of flashbacks, framed by the fictional device of Chaplin’s editor, played by Antony Hopkins, discussing the manuscript for Chaplin’s autobiography with the aged filmmaker (Robert Downey Jr.), living out his final days at his house in Switzerland (filmed in Chaplin's actual home near Vevey)

Chaplin's extraordinary performing and filmmaking career is set against his turbulent personal life, which, along with his political views, got him into a lot of trouble, and eventually resulted in him being deported. The film also deals sensitively with the trauma of his mother's mental illness. It is a very rounded portrait, with telling cameos by a cavalcade of fine British and American actors (look out for a very young David Duchovny, pre-X-Files, as Chaplin's cameraman). No performance is more poignant than that of Geraldine Chaplin playing her own grandmother. And at the center of it all is Robert Downey Jr.'s Charlie, a performance that is so fine you never for one moment think you are not watching the man himself.

The film is as much an ode to the early days of Hollywood as it is an examination of one of cinema’s supreme artists. In the silent era, Chaplin was the most recognized and famous man in the world, and his films shaped the nascent art form in many incalculable ways. His early Mutual shorts show slapstick elevated to an art form. His early feature The Kid (1921) - the original cross-generational buddy movie - turned Dickensian social commentary into both comedy gold and searing drama. The Gold Rush (1925) anticipates the surrealism of Bunuel's Un Chien Andalou (1929) with, amongst other moments, its shoe-eating scene. Chaplin may not have been the supreme technical and cinematic innovator and modernist that his fellow comedian Buster Keaton was, but in sequences like the opening of Modern Times (1936), where the lowly manual worker literally gets caught in the cogs of his own assembly-line, or Hitler’s dance with an inflatable globe in The Great Dictator (1940), Chaplin found perfect cinematic metaphors for his social and political concerns, and also made you laugh like hell.

Chaplin in "The Great Dictator"

Chaplin in "The Great Dictator"

Attenborough does a terrific (and accurate) job of portraying first the silent and then the early sound days of Hollywood. The film is shot beautifully by one of the greatest of all cinematographers, Sven Nykvist (Ingmar Bergman’s frequent collaborator). His photography - which never seems like it is lit by anything other than natural light - manages to feel both of the present moment and nostalgic at the same time. The music is a perfect match for the visuals, and each enhances the other seamlessly. (The production is A-List all the way: impeccable art direction by Stuart Craig who went on to create the Wizarding World of Harry Potter; costumes by John Mollo of Star Wars fame; and editing by the legendary Anne Coates of Lawrence of Arabia no less).

Because the film covers Chaplin’s career from his early days in English music-hall through his time in Hollywood, Barry is given many opportunities to compose musical pastiches of vaudeville and classic silent movie tropes, and he has a lot of fun doing so. One such scene is where Chaplin hits upon the idea for the dancing bread rolls he immortalized in The Gold Rush (1925) at a dinner party where one of the guests is a combative J.Edgar Hoover.

Chaplin - The Roll Dance

Another lovely touch is the integration of some of Chaplin’s own music into the score. (Chaplin was a talented composer, with a real gift for melody).

One of the most memorable instances of this is a sequence portraying the real-life shenanigans of Chaplin and his colleagues fleeing to Salt Lake City to try and finish editing a film in secret, recast by Attenborough as a silent movie chase complete with pratfalls and disguises. For this Barry re-recorded some of Chaplin’s own music from City Lights (1931).

Chaplin - Salt Lake City Episode

Chaplin’s composition “Smile” from Modern Times makes several appearances, and blends seamlessly with Barry’s own music - another indication of how perfectly Barry has matched Chaplin’s personality in his score.

Chaplin - News of Hetty's Death/Smile

Now all the musical extracts I have featured above are taken from the original soundtrack issue, not the La-La Land remastering by Doug Schwartz , which is impeccable and definitely an improvement. The original engineering was by one of the greats, Shawn Murphy, recording the English Chamber Orchestra at Abbey Road. I do not have information as to whether it was recorded analogue or digital, but given the fact that this was the 90s, I think it's reasonable to assume it was digital. For my taste the acoustic is perhaps a little too reverberant - I tend to prefer a slightly drier acoustic on film soundtracks - but on the flip side this creates a more blended sound. Murphy and Barry had already collaborated on Dances with Wolves (1990), and would work together again, most notably on the album Moviola, which is a must-buy for Barry fans.

This being a La-La Land release, every cue in the film and associated tracks are included. The disc is a great listen away from the film, as are most Barry soundtracks. Even the thematic repetitions do not pall because they are accompanied by subtle changes in orchestration. However, I will warn you about one track: Robert Downey Jr.’s pop rendition of “Smile”, released at the time as a single - a dubious commercial promotion for the film. One listen (out of curiosity) will suffice.

Incidentally, like most La-La Land releases, Chaplin is a limited edition, of 3000 units. If you are interested, do not delay. OOP titles go up in price.

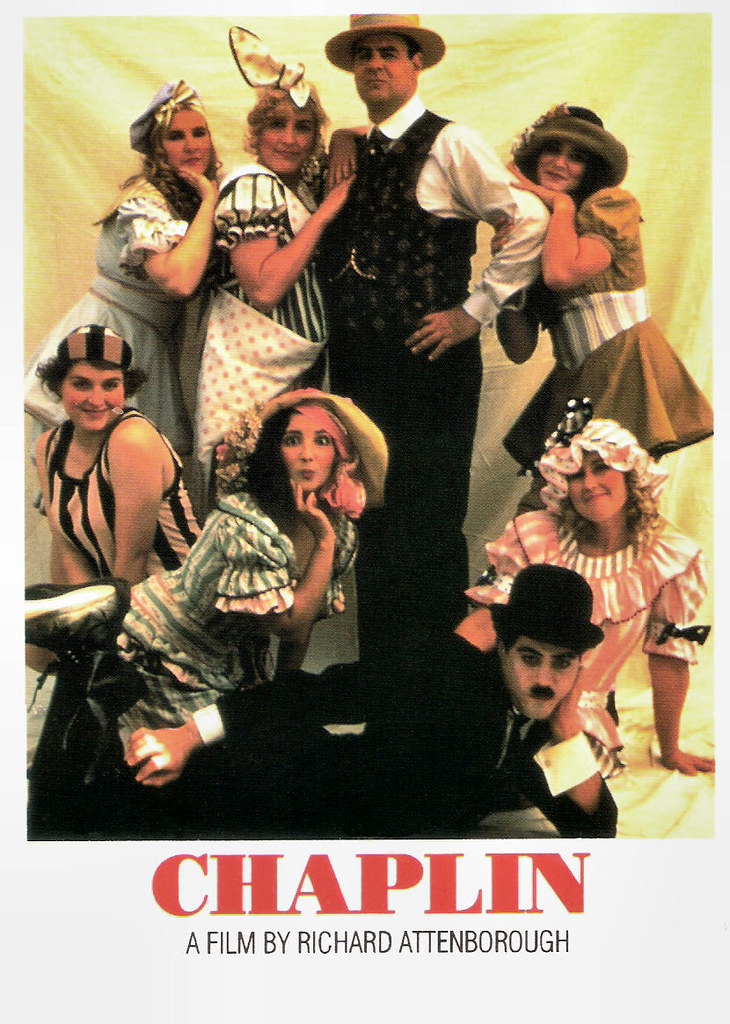

French Postcard Promoting the Original Release. (Dan Ackroyd plays Mack Sennett, Chaplin's First Hollywood Employer)

French Postcard Promoting the Original Release. (Dan Ackroyd plays Mack Sennett, Chaplin's First Hollywood Employer)

Time has been very kind to Chaplin. It pulls off the rare feat of being both a successful, three-dimensional (and reasonably accurate) biopic and a compelling drama with real depth - a rare combination. Add in the bonus of bringing early Hollywood to full, vibrant life, and a career-best performance by Robert Downey Jr. (woefully passed over for Best Actor at the Oscars) and you have something really special. By comparison, Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), showered with Oscar gold at the time of its release, now seems weighed down almost irreparably by its good intentions.

I think one of the reasons Barry's music for Chaplin is so special is because the film resonated with Barry's own love of cinema - after all he grew up helping out in his father's own chain of theatres in England. And the films of Chaplin were films that Barry knew from his youth. They belonged to a bygone age in every sense: of stories, mores, stars and glamour that had long receded by the 1990s. On some level, the score for Chaplin is Barry's own musical love-letter to the medium he loved so completely, and did so much to enrich.

Judged by this exemplary 30th Anniversary edition, I can only echo Jon Burlingame’s closing remarks in his booklet notes:

"Barry would score only ten more features after this one, few of them remembered today. Chaplin must qualify as one of his last great works for the cinema."

What to Listen to - and Read and View - Next

As mentioned above, the album Moviola is highly recommended, with stunning sound and truly symphonic performances by the Royal Philharmonic (Thomas Beecham’s old orchestra). I did eventually come upon the vinyl issue from a time (1992) when records were going the way of the dodo - the pressing is pretty ticky even after multiple cleanings, so unless vinyl is essential, I would be perfectly satisfied with the CD. The follow-up album, Moviola II, is less recommendable, for the reasons stated earlier.

If you want to go for a real late-John Barry audiophile experience, look no further than the ORG 2LP version of Dances with Wolves, still available at reasonable prices. (La-La Land did issue a CD expanded edition, but it is out-of-print).

For early Barry there are numerous vinyl possibilities - original soundtracks and re-recorded compilations by the man himself. (At a future date I will be covering a range of these records). One of the best of these, The Great Movie Sounds of John Barry, has been reissued AAA on impeccable 180gram vinyl by Speaker’s Corner. It bests my early pressing (which is no slouch either) and has the advantage of dead-quiet surfaces.

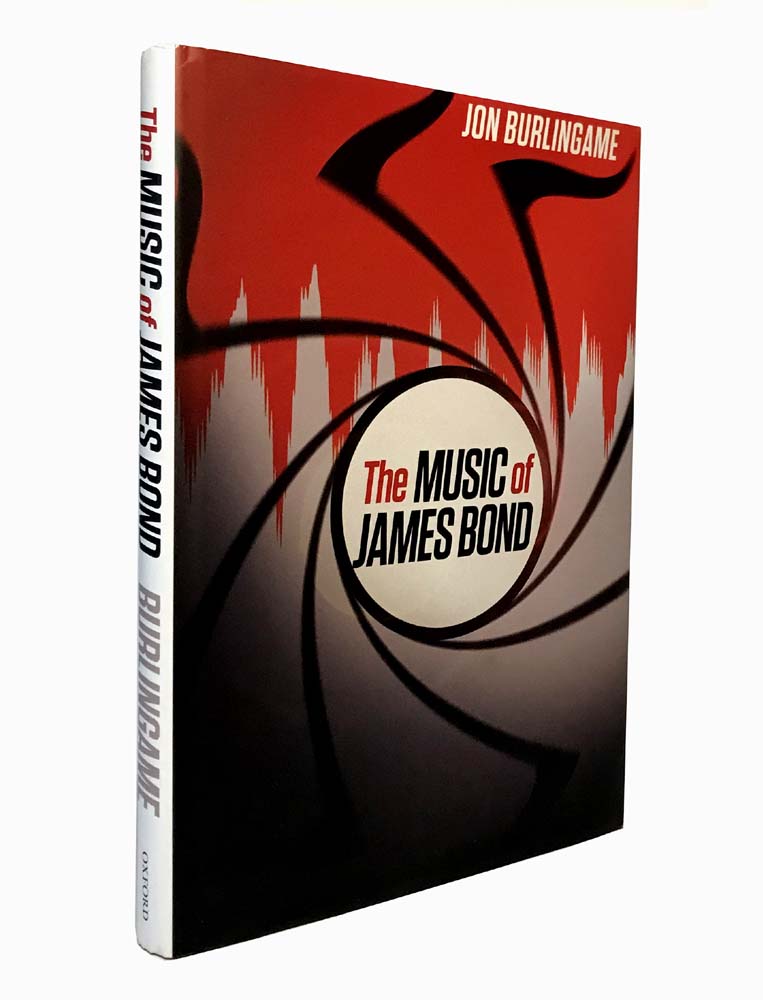

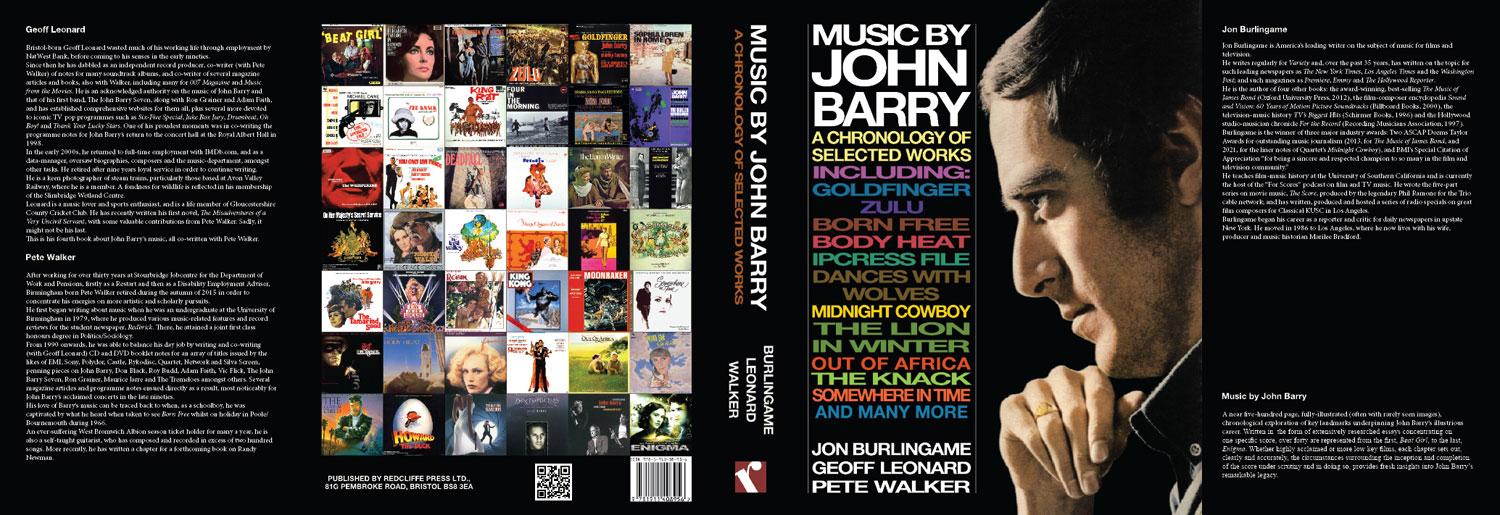

In the months ahead I will also be reviewing several books about John Barry that have come out in recent years, but I will not be giving anything away by recommending these highly now. First up, Jon Burlingame’s The Music of James Bond, a comprehensive look at all the scores for the series (minus the most recent films, Spectre and No Time to Die). I will echo the pleas of all Bond music fans for a fully updated new edition.

Burlingame is also one of the authors of the superb tome, Music by John Barry, also with a review pending. He is joined by renowned Barry expert Geoff Leonard, and Pete Walker, in detailed analyses of a wide variety of scores. This is a deep dive into the catalogue of one of the greatest and most influential film composers of all time, and in every way it matches the quality of its subject, with encyclopedic knowledge and insightful commentary every step of the way. Oh and did I mention, incredible period photos, plus ephemera associated with the films, that will make film score and movie buffs drool, all printed on thick glossy paper. It’s published by Windmill Publications, and available via mail order at a very reasonable price considering the riches it contains and its handsome presentation. Go to their website or send an email to musicby@johnbarry.org.uk.

You can also watch the excellent PBS documentary about Barry, "Moviola", filmed around the time he composed Chaplin. It's full of fascinating insights into Barry's process, and includes interviews with him and his collaborators Kevin Costner, David Attenborough, Sidney Pollack, plus a delightful interview with Kathleen Turner, the femme fatale of Body Heat (1981) for which Barry wrote a scintillating score. (You will have to make allowances for the picture and sound quality).

Finally, if you are a Chaplin fan, or even just a movie buff, and you haven’t seen it, seek out the superb 3-part documentary by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill (with music by Carl Davis) titled The Unknown Chaplin. Chaplin filmed and kept everything, including his rehearsals and discarded material, and this doc uses all this unique footage as the basis for an examination of his filmmaking methods. You can literally watch his films take shape in front of your eyes. You can find it on YouTube and Amazon.

In conclusion, a personal reminiscence. One evening some years ago I found myself going to a screening on the old Chaplin Studios lot on La Brea and Sunset in Hollywood (later A&M Records, now Jim Henson Studios).

Chaplin Studios in the 1920s, with a dusting of snow

Chaplin Studios in the 1920s, with a dusting of snow

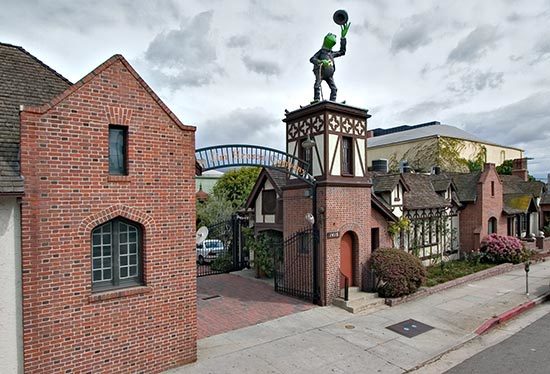

Jim Henson Studios Today (formerly the Chaplin Studios)

Jim Henson Studios Today (formerly the Chaplin Studios)

A friend who was hosting the event invited us into his office for a drink beforehand. As I stood there I suddenly had a moment of recognition: we were standing in what used to be Chaplin’s editing room, and it was more or less unchanged since he had worked there (it is the arched window to the left in the Henson Studios photo above). I knew this because I had seen a promotional short that Chaplin had made in 1918 about his new studios called How to Make Movies. I felt like I had literally stepped into history. That location features in Chaplin...

-- and you can see Chaplin editing there in that same short film below, beginning at 5:30.

How to Make Movies (1918)

.png)