Charles Lloyd's Zen Wonder

The "West Coast Coltrane," still vibrant at 85

Charles Lloyd is a wonder: 85 years old, still near the top of his game, his tone on tenor sax and flute clear and strong, not at all averse to risk-taking—in fact, keen to leap into new routes and approaches. Rather than hiring bandmates well suited to merely comping behind his solos, as some old masters do, Lloyd recruits the best musicians he can, to ensure a flow of adventure in the interplay. This has been true ever since his first major album as a leader, Dream Weaver (1966), where he was joined by Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette, before either of them was known. In the early 1990s, Lloyd was coaxed out of an early retirement by an encounter with the piano wunderkind Michel Petrucciani. Ever since, he has formed small groups with the likes of pianists Geri Allen and Brad Mehldau, guitarists John Abercrombie and Bill Frisell, drummers Billy Higgins and Eric Harland—all of them masters, leaders in their own right, not the sorts of players you’d hire to tap out 2-5-1 changes or 4-4 beats in the background.

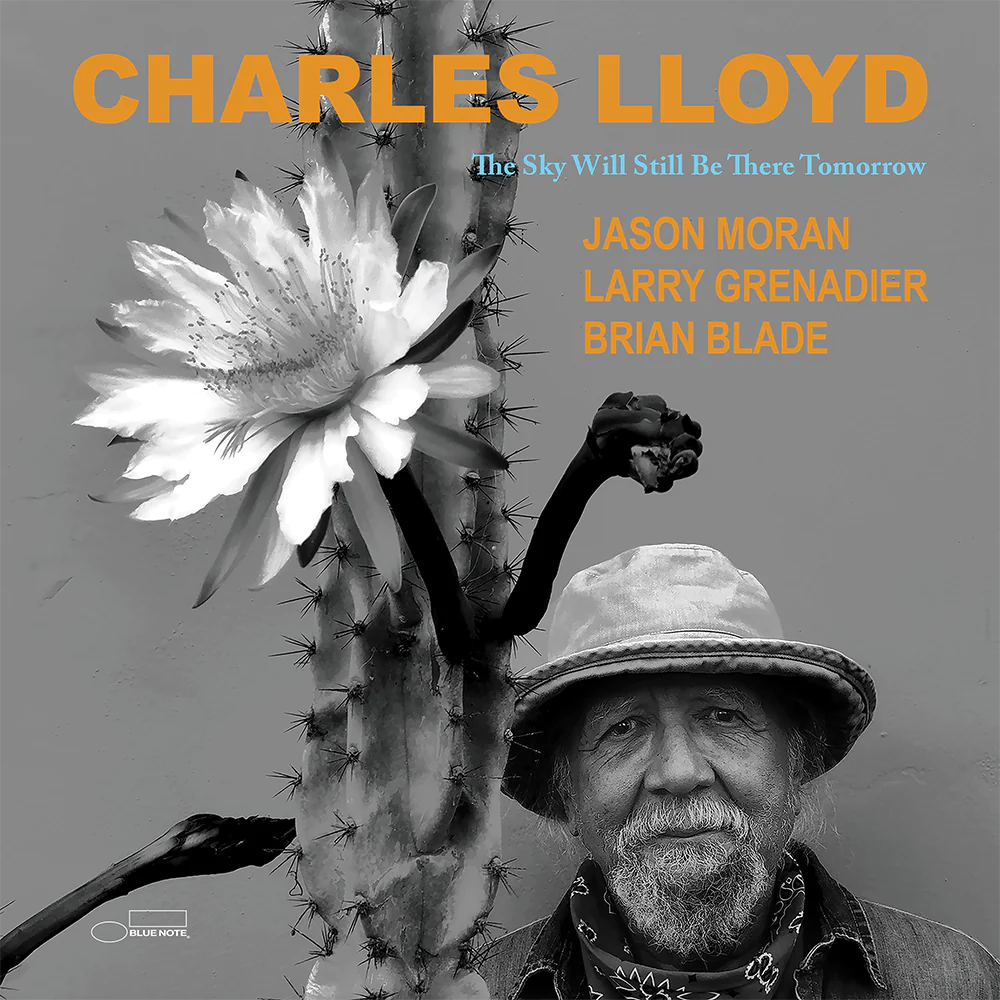

Lloyd’s latest, The Sky Will Still Be There Tomorrow, follows the same pattern, featuring Jason Moran on piano, Larry Grenadier on bass, and Brian Blade on drums—players 25 to 35 years Lloyd’s junior, and as insistently high-level a quartet as any he’s ever assembled.

The first track, “Defiant, Tender Warrior,” starts with assertive percussive rumbles from Blade, which segue into Moran coaxing a reverie that sounds like something from his own songbook, which, after it settles into a groove, Lloyd wends his way into, as an equal. Lloyd and Moran have had a special relationship ever since Rabu de Nube (2006), their first of six recorded collaborations. (In his liner notes, Lloyd writes that he and Moran share a language “that is neither from Webster nor King James…drawn from a deep well of love for sound and a deep love for the mystery that lies in the search for that sound.) “The Water Is Rising” is another track on this album that has strong Moran-ish overtones.

None of this is meant to minimize Lloyd’s contribution to the mix, which is front and center (and not just in terms of soundstage). I’ve referred to Lloyd as the “West Coast Coltrane,” meaning he fuses Trane’s hard tone and sheets-of-sound rapture with a swaying swing and a Zen-like disposition. The Sky Will Be There Tomorrow is a bit more Zen than usual (beginning with its title). It tends, more than usual, toward slow, meditative, sometimes mellow: there are more whole notes and longer breaths. Still, this is, for the most part, invigorating music, in part because this band keeps it moving. When Lloyd stretches a phrase, Blade klook-a-mops in triple time; when the harmony glides on a plateau, Moran splatters bright color notes or Grenadier walks a crooked scale. The landscape quakes, the wind swirls, the light fractures into prisms of color and shade.

Sit back, listen closely, this is a gorgeous album—again, for the most part. At times, the tension slackens, the scale-runs settle into modal noodling—still pleasant, but not much more. There’s 90 minutes of music here, spread out across two slabs of vinyl (or two compact discs), and if the producers had scuttled a third of it, they would have done no harm. Nonetheless, the remaining two-thirds are vital and extraordinary.

The sound quality throughout is excellent. Dom Carmadella, who has engineered Lloyd’s last several albums, captured the ensemble with an array of mainly vintage Telefunken microphones—a U47 on Lloyd’s tenor sax, a C-12 on Moran’s piano, a 251 on bass (with a little direct-input stirred in), a Neumann 84 and Shure 57 on the drum kit, and some ribbon mikes for the room. He laid down the tracks on high-rez ProTools (per usual these days) but mixed them on an analogue Neve console. Joe Harley (who supervises the Tone Poet productions) then rejiggered the panning, so the soundstage resembled the lay-out that you would see and hear at a jazz club. It sounds warm and vibrant and true.

listened to the CD a couple of times before the LP arrived. It sounded very good, but the vinyl is way better, in the usual ways but not subtly. The born is more dimensional; the piano more detailed, percussive, and blooming with harmonics; the bass has more pluck and wood; the drumkit more smack and sizzle; there’s more sense of a room and of human beings making music there.

I saw this quartet play live at Lincoln Center last fall, as part of a “Charles Lloyd at 85” celebration. He was remarkably unflagging, the band hoisting him high and egging him on. He stands among the last of his generation’s still-active great horn players. His only elders are Archie Shepp, at 86, and Marshall Allen, the Sun Ra sidekick who still leads a band of Ra acolytes, who’s just a month short of 100. They are all, in their own ways, treasures (I see that Mr. Lloyd has turned 86 since the album was recorded. I am told he is still blowing strong).

.png)