Sir Colin Davis: Classic Sibelius in Boston in State of the Art Sound *

Remastered by Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer, it is one of three recordings chosen to launch Decca’s new Pure Analogue series vintage Decca and Philips classics from the Seventies

The Composer

The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony began as a gift to himself. The government of Finland commissioned it to honor his fifth round-number birthday on 8 December 1914. By this time, a good quarter century into his career, he was universally regarded as the country’s greatest composer. Born in 1865, five years after Mahler, the same year as Carl Nielsen, also the year that heard the premier of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, Dvořák’s Cello Concerto and First Symphony, and several of Brahms’s major chamber works, Sibelius initially studied law before transferring to the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy), where he came under the tutelage of Ferruccio Busoni, his first important mentor, who encouraged him to become a composer. Sibelius later pursued advanced studies in Berlin and Vienna, where in 1891 he began Kullervo (completed a year later), a five-movement symphonic work (with soloists and male chorus) named after the Finnish hero of the Kalevala, a collection of epic poetry that tells the story of the creation of the world and that was also a recurrent source of inspiration throughout the composer’s life.

Although Sibelius did not write Kullervo as a symphony, he often referred to it as one, and long before he finished his Seventh and final numbered symphony, critics followed suit, calling it his real first symphony. Four Legends from the Kalevala (AKA Lemminkäinen Suite), the collection of four tone poems that followed in 1896, was the second longest work of his career (after Kullervo).[1] Many critics, notably David Hurwitz, author of Sibelius Orchestral Works: An Owner's Manual and one of the composer’s most astute critics, consider it his second unnumbered symphony. Sibelius wrote his first “proper” (i.e., numbered) symphony three years later and finished the Seventh, his last numbered one, in 1924. Two years after that he wrote his last major composition, the tone poem Tapiola, named after Tapio, a forest spirit that appears throughout the Kalevala. Like the Seventh, Tapiola, though a one-movement piece, is so tightly knit internally that it is not infrequently regarded as a symphony.[2]

Then nothing, or next to nothing: the so-called “silence from Järvenpää," named after the location of the Sibelius family home. After three decades of astonishingly productive and accomplished compositions, many of them highly innovative, several of them masterpieces, the next three yielded no more major music except the so-called Eighth Symphony, which he worked on for around a decade and a half but never finished, eventually burning the manuscript, along with those of several other pieces, sometime in the forties. The “great auto da fé,” is how Aino, his wife, referred to the day this happened, which took place in the fireplace of the dining room. “I did not have the strength to be present and left the room,” she later recalled. “I therefore do not know what he threw onto the fire. But after this my husband became calmer and gradually lighter in mood.” The composing silence continued, however, and ended only with the permanent silence of his death in 1957 at the age of ninety-one.

Why did he stop composing? As the composer himself was almost completely silent on the subject, theories and speculation abound: his intense self-criticism, an admirable trait for an artist unless it becomes paralyzing, which it apparently did with him; a belief that he had carried his own symphonic development as far as he could; a feeling that he was becoming increasingly out of touch with and antipathetic toward the direction of modern music together with a fear of the irrelevance of his own; health issues, including depression exacerbated by lifelong alcoholism; and, ironically, freedom from financial insecurity.

This last is poignant. Sibelius’s music was popular, well loved, and highly respected by audiences throughout both his active and his silent years, and performances of his music proliferated in concert halls around the world. (This eventually resulted in a substantial enough increase in his royalties until, along with other income from conducting fees, publication rights, and a generous government pension, he eventually cleared all his debts, which enabled him and Aino to live the remainder of their lives in prosperity.) In fact, it was only with a relatively few prominent critics and with certain “elite” factions of the musical public that his reputation fluctuated and even generated a fair amount of controversy, notably in places where the avant-garde was strong, such as Germany and the United States. In a 1938 review the German philosopher and musicologist Theodor Adorno, a great theoretical thinker who was also a lousy critic owing to his ideological biases (you’d be surprised how often those attributes go hand in hand), savaged him, declaring, "If Sibelius is good, this invalidates the standards of musical quality that have persisted from Bach to Schoenberg." Adorno shared his hostility with Virgil Thomson, who warned his German colleague to tone it down lest he alienate his readers.

Yet in 1940 Thomson himself, in his opening column as the newly appointed music critic for the New York Herald Tribune, a post that helped establish him as one of the most important music critics in the country, judged the Second Symphony, Sibelius’s most popular, "vulgar, self-indulgent, and provincial beyond all description.” If that’s toning it down, this must be one of the most shameless examples of the pot calling the kettle black in the annals of music reviewing. Fifteen years later the avant-garde composer/conductor René Leibowitz, like Adorno another ideologue committed to the serialism of the Second Viennese School, went further: “Sibelius, the worst composer in the world” was a pamphlet Leibowitz published on the occasion of the composer’s ninetieth birthday.

“Pay no attention to what the critics say. No statue has ever been put up to a critic,” Sibelius had said many years earlier, in one of the most widely quoted dismissals in the history of music.[3] Yet any negative review, especially any such review from a source not easily dismissed, seemed to distress and depress him in equal measure, to such an extent that, together with his relentless self-criticism, he developed an addiction to cigars (and only the best), vodka, gin, cognac, premium whiskies, very expensive wines and champagnes, and equally expensive fine dining (oysters and lobsters particular favorites). He liked to throw lavish dinner parties for his drinking buddies at the priciest restaurants. Catering to these vices, tastes, and lifestyle choices incurred a pretty constant series of debts that went on for decades (all, according to his biographers, eventually paid back).

Many artists live lives of excess, much of the time without affecting their work too deleteriously. But Sibelius’s addictions directly affected his music and musicmaking in some ways good, in others, and mostly, for the worse. “There is much in my make-up that is weak,” he wrote to his brother Christian, who was one of the founders of modern psychiatry in Finland and even treated Jean from time to time, but “when I am standing in front of a grand orchestra and have drunk half a bottle of champagne, then I conduct like a young god. Otherwise, I am nervous and tremble, feel unsure of myself, and everything is lost.”

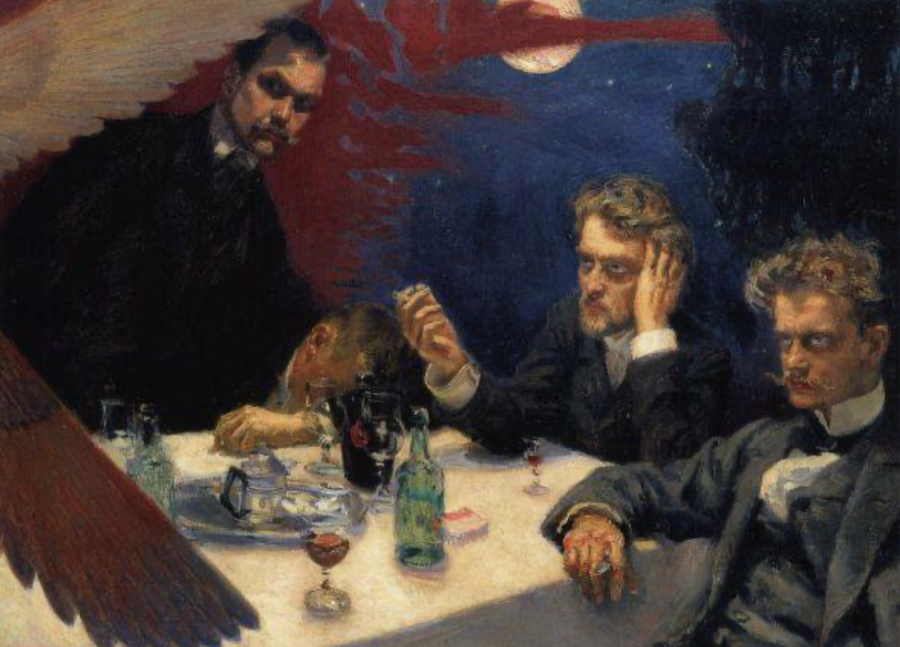

Titled Symposium and painted by the Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela, this scene depicts a group of Finnish intellectuals and artists who gathered on a regular basis for good food and good talk washed down with copious amounts of alcohol. The painter himself is far left; center is the conductor Robert Kajanus, an early champion of Sibelius and a widely respected interpreter of his work; far right is the composer himself, obviously well into his cups.

Titled Symposium and painted by the Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela, this scene depicts a group of Finnish intellectuals and artists who gathered on a regular basis for good food and good talk washed down with copious amounts of alcohol. The painter himself is far left; center is the conductor Robert Kajanus, an early champion of Sibelius and a widely respected interpreter of his work; far right is the composer himself, obviously well into his cups.

Drinking and smoking also affected his health. In 1908 a malignant tumor was discovered in his throat and required at least thirteen operations to remove it. The cancer never returned—his was an extremely hardy constitution—but the scare was enough for him to heed warnings his physicians had been giving him for years. He managed to do completely without smoking and drinking for around seven years, during which he wrote some of his darkest pieces (the grim Fourth Symphony, The Bard, and Luonnotar). Many friends and commentators believe these were written while still in the grip of his brush with mortality.

It was only when he commenced the long process of writing and revising his Fifth Symphony, which did not come easy, that the hyper self-criticism, the debilitating self-doubt, the extreme anxiety, the sheer effort required to get it into a shape that satisfied him—all caused him to turn to drink again. He both drank and smoked to excess the rest of his life. Not surprisingly, these habits threatened his marriage.[4] Aino, who repaired to a sanatorium for a while owing to the stress of living with a drunk, threatened divorce, but she never left him.

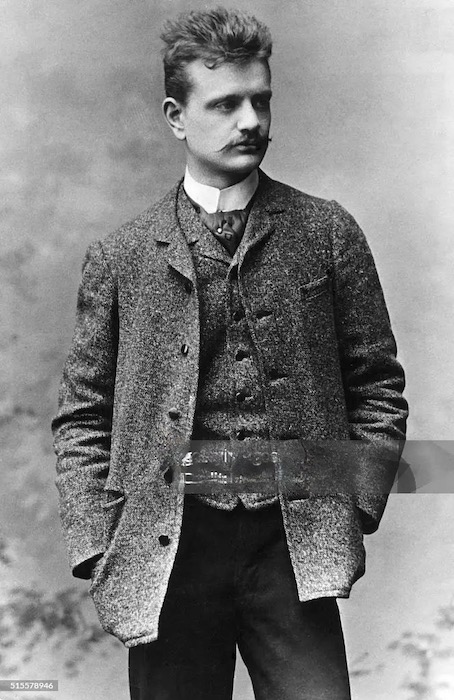

Sibelius as a young man about the town—raffishly good-looking, always stylishly dressed

Sibelius as a young man about the town—raffishly good-looking, always stylishly dressed

The strikingly beautiful Aino at twenty, when she and Jean were married

The strikingly beautiful Aino at twenty, when she and Jean were married

He handsome, charismatic, a stylish dresser, she a young beauty, they had fallen in love virtually at first sight; from the beginning she had encouraged him to write symphonies; they had six children; when home he was drunk a lot of the time, away from home he indulged periodic binges, yet they remained devoted to each other the rest of their lives. (It’s reported she wrote him over 400 letters, he over 700 to her, many far too intimate to be made public.) Around the time he turned eighty he remarked, “All the doctors who wanted to forbid me to smoke and to drink are dead. But I go on living.” Reflecting on sixty-five years of marriage, Aino said, "I am happy that I have been able to live by his side. I bless my destiny and see it as a gift from heaven. To me my husband's music is the word of God—its source is noble, and it is wonderful to live close to such a source."

Despite behavior of his that when drunk almost ended their marriage, Jean and Aino remained devoted to each other to the end of their lives.

Despite behavior of his that when drunk almost ended their marriage, Jean and Aino remained devoted to each other to the end of their lives.

It would take a heart much harder than mine to be wholly unsympathetic to the composer here. He returned to alcohol to lift himself out of depression and, more important, as a way to silence or at least keep at bay what appears to have been almost pathological self-criticism. Yet long-term alcohol use, we now know, typically leads to depression rather alleviating it; and through at least the first half of Sibelius’s life, many doctors were still prescribing alcohol for medicinal purposes!

If periods of depression and despair continued throughout Sibelius’s last thirty years, he nevertheless did live long enough to realize how popular his work was with audiences. In a 1935 poll conducted by the New York Philharmonic, concertgoers named Sibelius their favorite composer, living or dead. He also lived long enough to see the beginnings of the extensive influence his music would exert on younger composers in Finland and other Scandinavian countries, then in the world beyond, particularly England and America.[5]

Finally, throughout his career Sibelius was appreciated by many of the world’s most prestigious critics, such as Sirs Ernest Newman and Donald Francis Tovey in England and Olin Downes and Alfred Frankenstein in America, and he lived long enough to see the critical consensus begin to shift significantly in his favor. But what he did not live to see is how overwhelming the shift would be, to the point that even some members of the avant-garde began to recognize how original he really was. This happened to be marked by an actual occasion: a lecture delivered in 1984 by Morton Feldman, as righteous and uncompromising an avant-gardist as ever lived, at what the critic Alex Ross called “the relentlessly up-to-date Summer Courses for New Music” in Darmstadt, Germany. “The people who you think are radicals might really be conservatives,” Feldman said. “The people who you think are conservative might really be radical.” Whereupon he started humming Sibelius’s Fifth.

Even if it took sixty years in the case of Sibelius, a surprising number of those musical elitists who fancied themselves Vox Dei finally did catch up to Vox Populi.

Two Symphonies and a Tone Poem

It has often seemed to me ironic or at least curious that Sibelius chose to base his greatness as a composer on symphonies. The classical symphony was a fairly strict form that celebrated variety and high contrast in four parts or movements: the first a lively allegro, the second essentially a song for orchestra, the third a dance, the fourth another allegro, typically high-spirited, sometimes humorous, other times dramatic, still other times triumphal. Sibelius’s first two symphonies are big, epic works of late romanticism, nationalistic in spirit, grand in gesture, and powerful in the manner of Tchaikovsky and Bruckner, two composers he much admired and was proud to number among his influences. It is a measure of Sibelius’s achievement that by no means do these two early symphonies exist in the shadow of their towering predecessors, instead standing proudly, confidently, magnificently on their own in the sunlight.

But in his last five numbered symphonies Sibelius embarked on a new path—my allusion to Beethoven’s famous pronouncement in 1802 is intentional—whereby he resolved to seek a greater internal unity among the traditional symphonic movements, a unity that embraced all elements of the symphony. Melody, theme, motif, key, harmony, tempo, orchestration, and expression must all have an inner connection that unites the disparate movements into a whole which is not only organic but teleological, that is, embodying a final purpose and meaning that grows inevitably out of the materials. In “Sibelius, form and substance are indivisible,” writes Robert Layton, in The Master Musicians: Sibelius, his comprehensive and invaluable critical study. “And it is that unity of matter and manner, of content and form that make the last symphonies so remarkable” (5).[6]

The first time I read this, I was reminded of Emerson’s famous pronouncement in his essay The Poet that “it is not metres, but a metre-making argument that makes a poem,—a thought so passionate and alive that like the spirit of a plant or an animal it has an architecture of its own and adorns nature with a new thing.” Here is Sibelius writing in his diary: “I let the musical thought and its development in my mind determine matters of form,” whereupon he likens a symphony to a river “made up of countless streams all looking for an outlet, [the] movement of the water determines the shape of the river-bed: the movement of river-water is the flow of the musical ideas and the river-bed that they form is the structure” (quoted in Layton, 5).

The philosopher’s and the composer’s use of nature as metaphor to explain their aesthetics is revealing. The combination of the natural world and the myths of the Kalevala inspired some of Sibelius first steps toward his quest for a new structural coherence and organicism in symphonic form. He was one of the truly great nature composers. This is not just a matter of musical onomatopoeia like chirping birds, mooing cows, babbling brooks, and raging oceans, though of course he knew all about those too. Rather, it is that he was able to create an aural equivalent—T. S. Eliot would have called it an "objective correlative," a concept he began to formulate more or less at the same time—to land- and seascapes that doesn’t just evoke but seems to conjure an almost physically immediate sense of what it feels like to be immersed in them: the very texture of the air, the weight of the atmosphere, the brooding clouds and towering mountains, the wintry northern light and shade. No composer known to me before Sibelius ever came anywhere near his ability to achieve these ends. And only a few rivalled him: Debussy, Copland in his “prairie” ballets, the Britten of Peter Grimes, not many more, and none with his precision and ability to do it over and over without repeating himself.[7]

Sibelius was already well on his way to developing a highly individual approach to sonata, but once he was on his new path it became intensely expressive in a deeply personal way. Meanwhile, as regards the relationship of the movements and the overall architecture of the symphony, the radical formalist emerged. Each symphony must be a new beginning that leads to a new ending and must eventuate in a new form. After the late-romantic grandeur of the first two, the Third, begun in 1904, premiered in 1907, was small in scale, precisely sculpted, with only three movements (marking the first time he made one serve the purpose of two). Here was neoclassicism before the term ever became current, the critic Michael Steinberg said it reminded him of Haydn. Others invoked Beethoven, though all were careful to note not as models Sibelius imitated but from which he took inspiration. The Fourth was an even more decisive departure from what came before: tough, dark, cold, and bleak, the composer experimenting with bitonality (for which reason, among others, it found some favor or at least less opprobrium from the serial-minded crowd) and plumbing the form to virtually private depths of feeling.

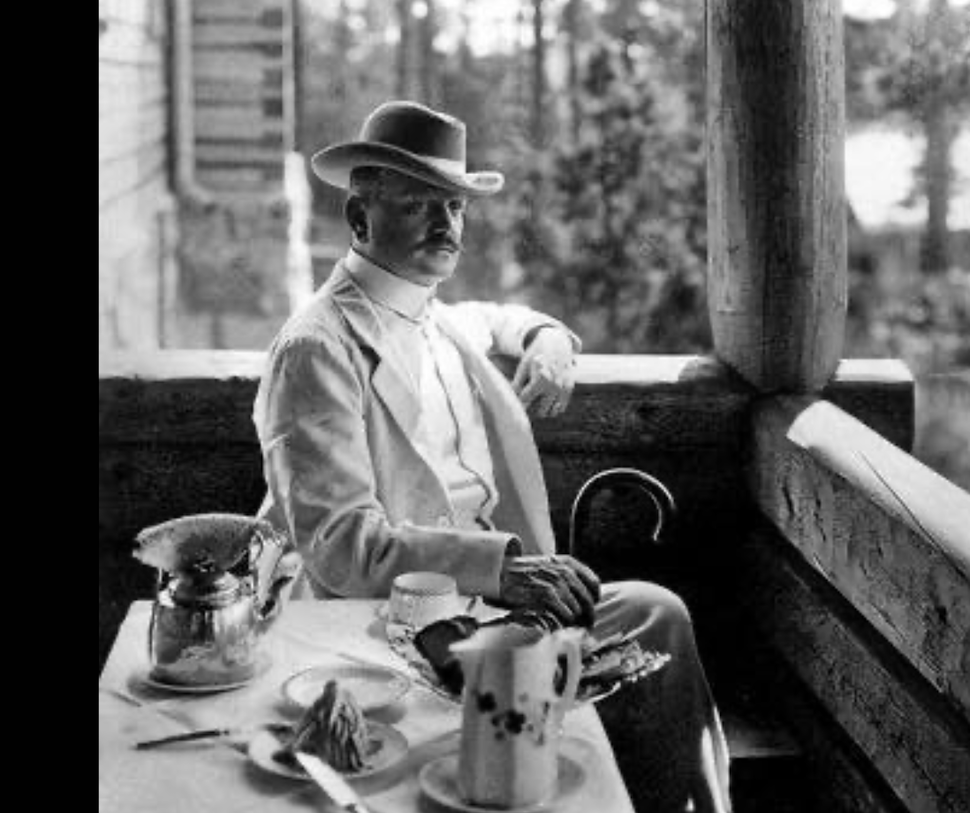

The lion in winter with ever present companion—a cigar. The popular image of Sibelius is as a stern severe bald old man. In fact, owing to a thinning hairline, he shaved his head in his early fifties. But he was also looking to cultivate a new image to go along with the shift in his music toward what he called the “pure, cold water” of the Sixth Symphony and later. Shaving his head bald gave him a sculpted, granite look that suited his new aesthetic priorities.

The lion in winter with ever present companion—a cigar. The popular image of Sibelius is as a stern severe bald old man. In fact, owing to a thinning hairline, he shaved his head in his early fifties. But he was also looking to cultivate a new image to go along with the shift in his music toward what he called the “pure, cold water” of the Sixth Symphony and later. Shaving his head bald gave him a sculpted, granite look that suited his new aesthetic priorities.

Sibelius’s last three symphonies are often treated by critics and musicologists as a sub-group among the composer’s symphonic oeuvre. His diaries suggest that he began thinking about them more or less at the same time, around 1914, and their compositions eventually became interlaced. At one point in a 1918 letter to his German publishers, he even considered introducing them at the same time. This was soon abandoned, presumably because by then he had not finished the extensive revisions to the Fifth.

“As far as we know,” Layton writes, Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony gave him “more trouble than any other work, for he mentions [it] as early as 1912 in his diaries” (83). It received its first performance in 1915, conducted by the composer, who was not happy with it. He revised and conducted it again the next year but was still not satisfied. It took him until 1919 to get the masterpiece we know today in a form he was ready to call definitive, and again he conducted the performance. Differing substantially from this final version, the first version can be heard on Osmo Vänskä’s 1997 premiere recording with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra on the BIS label.

The differences are remarkable and in at least two instances rather shocking. The 1915 first movement is prolix, distended, and, hard as this may be to believe until you’ve heard it, lacking in the one quality which in the final version it possesses above all: a brilliant driving primal energy that accelerates from scherzo to presto to più presto (“as soon as possible”). The original second movement, the scherzo, was presumably meant to provide this energy but it comes too late to rescue the protractions of the first movement and is further crippled by the decisive break between the two movements. Sibelius’s solution was blunt: combine the original first movement shorn of its second half and the original second movement shorn of its first half. That’s a crude way of putting it, but not all that far off the mark, except for the newly added transition, which profoundly changed the entire character of the piece.

In his seminal study of the Fifth, written in 1993, the eminent musical theorist and musicologist James Hepokoski shows how the opening of the sonata-like first part is developed according to a process he termed “rotational form,” whereby “the composer initially presents a relatively straightforward ‘referential statement’ of contrasting ideas . . . a series of differentiated figures, motives, themes, and so on” which are then returned to and rotated with variations, transformations, expansions, compressions, etc.; “each subsequent rotation may be heard as an intensified, meditative reflection on the material of the referential statement” (25).[8] This first paragraph is rotated three times, each building to a big brassy heavy climax. Out of the third climax, in David Hurwitz’s vivid description, “the harmony gradually begins to clear until suddenly the sun bursts out in the form of the opening Kalevala tune.” Then, in one of the most magical transitions in the history of music, the tempo picks up and before we realize it we find we’ve been whisked, like Dorothy and Toto out of the tornado, into the sunlit world of the scherzo on our way toward the most breathless, exhilaratingly thrilling final peroration of any symphony, which stops in tempo on the dime, leaving us suspended before we’ve had time to exhale. A stunning effect.

The second movement is an andante/allegretto set of variations that twice adumbrate themes in the heroic third movement, itself shorn of some 200 bars for the final version. It opens with a flurry of rushing string and wind tremolos that create a furiously whirring effect, upon which Sibelius soon plies a theme inspired by the sight of sixteen swans in flight at sunset near his home. This may be the most majestically plangent theme ever written—once the image gets implanted in the mind it’s almost impossible not to envisage the coordinated rise and fall of the long wings beating blissfully in soaring slow motion. The movement ends with a stroke of genius even bolder than the headlong tumultuous peroration of the first movement: six block chords spaced such that they resonate only in the utter silence that separates each one from its neighbor. The BIS recording of the 1915 version reveals something even more shocking than the lack of energy in that version’s first movement: an underlying bed of tremolo strings and winds that actually fills in the silences of the final version! Sibelius’s unremitting self-criticism may have put him through the tortures of the damned, but when you hear the earlier version of this ending you will be grateful that he was never satisfied until he was thoroughly satisfied according to the highest standards he set for himself.

The cuts and reworkings served also to clarify and firm up what might be called the macro-structure of the Fifth, which I’ve always thought of as a colossal arch spanned by the deceptively gentle variations of the second movement—deceptive because though it is often viewed as a kind of pastoral interlude between the near cosmic blaze and brilliance of the first and third movements, Hepokoski argues that its “larger purpose is to generate the leading rhythms, meters, timbres, motives, and themes of the finale to come” (71). This gives the movement a deep structural function that is obscured it is when viewed only as a lovely interlude. Hepokoski’s argument is fortified by the fact that Sibelius marked the opening of the third movement attacca, meaning immediately, with absolutely no pause, and it alludes in a strange way to the end of the first movement. There we are left suspended with breath held; the allegretto at a much slower tempo also ends abruptly with absolutely no indication that the phrase is to be played other than in tempo, so the attacca instruction ensures the whirling strings and winds descend before we’ve had a chance to breathe: same idea, wildly different means and realizations. (It is a shame that so many recordings fail to observe the attacca direction, instead inserting a pause that totally undermines the effect the composer had in mind.)

In the final three-movement version, the flanking movements stand like massive symmetrical pillars: the first slow and craggy, then cataract-like cascading faster and faster; the third opening with rapid tremolos bristling with irrepressible energy until the great swan theme appears and the forward motion of both the movement and the symphony at large gradually gets slower and weightier and grander until all the pent-up energy at last erupts in those final six stark chords.[9]

The composer in middle age—always impeccably groomed and attired

The composer in middle age—always impeccably groomed and attired

Sibelius wrote the Fifth in what appears to have been, rather typical for him, alternating states of despondent self-pity and near religious euphoria. In the very early stages, he wrote in his diary: “Now I shall be 50. How miserable it is that I must compose miniatures.” A letter around the same time to a close friend is almost rapturous: “God opens His door for a moment and His orchestra plays the 5th Symphony,” only to lament almost immediately that the almighty has already closed the door. Another diary entry: "Spent the evening with the [Fifth] symphony. It is as if God the Father had thrown down mosaic pieces from heaven's floor and asked me to put them back as they were.” (Handel seems to have had similar experiences writing Messiah.) A few days later comes the epiphany of the swans: "Today at ten to eleven, I saw 16 swans. One of my greatest experiences! Lord God, that beauty. They circled over me for a long time. Disappeared into the solar haze like a gleaming, silver ribbon.”

The critical and scholarly consensus is that the earlier versions of the Fifth, following upon the desolate Fourth, were darker in terms of mood and tone (among other things, there were additional flirtations with bitonality). But Sibelius never managed to realize any of that into a coherent, focused, and unified musical vision. By his own admission when he set about the revisions, he decided he didn’t want the Fifth to be grim and gloom laden: "I wished to give my symphony another—more human —form,” he wrote in his diary in 1918-19, as the revisions were nearing completion. “More down-to-earth, more vivid." He might also have added “heroic,” “uplighting,” “accessible.” He succeeded spectacularly, not least because these positive elements are developed and expressed at the expense of absolutely no dumbing down or compromising of his procedures and aesthetic ideals. On the contrary, the Fifth emerged an innovative work of great formal sophistication, emotional depth, and psychological complexity. Part of the reason for this is that the passages of exhilaration, uplift, and triumph are tough minded and hard-won. And like all great music, they are susceptible of several different interpretations, some of them quite antithetical to the apparent meanings. How could it be otherwise with this composer, who in 1943 called his Second Symphony “a confession of the soul”? But for a composer as personal as he, this could be said of all his symphonies. He was no more capable of suppressing his agonies than he was his joys.

Researching this essay, I came across a passage in Sibelius’s diary quoted by many: “Isolation and loneliness are driving me to despair,” he wrote. “In order to survive, I have to have alcohol . . . Am abused, alone, and all my real friends are dead. My prestige here at present is rock-bottom. Impossible to work. If only there were a way out.” This was written in 1927, not long after he had completed Tapiola and not long before the silence from Järvenpää" would commence, when he still had thirty more years stretching before him. When I read that, I thought immediately of the Fifth’s final six chords. These have been variously described as heroic, as triumphal, as defiant, as affirmative, as frightening, as graceful—the great critic Sir Donald Francis Tovey even likened the Swan theme, from which they grow out of, to Thor swinging his hammer, an image that casts them in the very different light of raw god-like power exercised with Olympian detachment. But from the perspective of that diary entry, with its ominous hint of suicide, those six chords strike me as primal cries flung out of great despair into the face of oblivion.

Sibelius made the three separate movements of the Fifth so interconnected that it appears to be through composed, moving inexorably with single purpose from its opening horn calls to those six amazing hanging chords. The enigmatic Sixth lacks a designated key but is dominated by the Dorian mode, and it has a last movement in which the theme seems to deliquesce before our very ears. But the Seventh and Tapiola go even further than the Fifth in seamless integration. The symphony, a monothematic work in a single movement, is one of the most staggeringly original works in the entire symphonic literature. According to Layton, Sibelius did not set out to write a one-movement symphony, and in fact at its first performance it was called Fantasia sinfonia No. 1, “a symphonic fantasy.” Written in the then-unfashionable—among the avant-gardists—key of C-major and built upon a theme announced by a trombone, it achieves through constantly shifting tempos, dynamics, modulation, and moods so unprecedented a unity of feeling and form in a symphonic work as to be resistant to any sort of conventional or academic analysis.

Tapiola goes even further into monothematicism, its basic theme so spare and short many critics and musicologists question whether it’s a theme at all, as opposed to a germ or even a gesture. In its extreme concentration and concision, it is Sibelius’s most modern work, not only in a single movement and monothematic but monotonal as well, yet with highly chromatic passages where the key is so ambiguous many commentators have felt that the composer pushes the limits of tonality to an extreme without breaking off from it. Tapiola is also Sibelius’s last great piece of nature music, where he prefaced the score with a quatrain of his own devising: “Widespread they stand, the Northland’s dusky forests,/Ancient, mysterious, brooding savage dreams;/ Within them dwells the Forest’s mighty god,/And wood-sprites in the gloom weave magic secrets.” Even by Sibelian standards, the atmosphere is of an extraordinarily intense and sustained brooding.

There is a structure that suggests an arc: introductory exposition that “exposes” the core germ motif with disquieting urgency, then a stormy development, last a coda that leaves us in the silence of the primordial forest. Tapiola’s forward motion is a series of ceaseless metamorphoses of theme, tempo, harmony, and texture that yet, paradoxically, resolve themselves into periodic passages of almost complete stasis without ceasing to be in motion. It is a work of such concentration and structural concision that for Ernest Newman there is “in the final result, not ‘a form’ at all, but simply form” itself: “no first and second, no egg, no chicken, in the matter of the idea and the form: each is just the other” (quoted in Layton 91). So many critics and other commentators in explicating this piece use the word “organic” and its variants or draw upon living things as metaphors that I am reminded of Emerson again, this time his famous description of Montaigne’s prose: “Cut these words, and they would bleed; they are vascular and alive.” Substitute “sounds” or “notes” or some such and Emerson’s statement applies with unerring accuracy to the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and Tapiola.

The Conductor

Long before Sir Colin Davis graduated from London’s Royal College of Music, where he studied clarinet, he knew he wanted to be a conductor but was not allowed to change to a conducting major because he did not play the piano. After receiving his diploma, in 1945, he began studying conducting on his own, reading books and manuals about it, observing how conductors rehearsed and led the orchestras in which he played as a freelance clarinetist, occasionally conducting small ensembles and choral groups around London. Over the next few years he had so honed his art and craft that he was asked to substitute for an ailing Otto Klemperer in a Don Giovanni at Royal Albert Hall and a year later for an indisposed Thomas Beecham in The Magic Flute at Glyndebourne. “A conductor ripe for greatness,” The Times pronounced him, “a master of Mozart's idiom, style and significance.” (Throughout his long career Davis was always hailed as a great Mozart conductor.)

These successes effectively launched Davis’s conducting career, soon leading to appointments as the music director of Sadler’s Wells Opera in 196, several concerts at the Proms over the next few years, and chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1967. Throughout the first half of the sixties Davis’s reputation was still confined principally to the United Kingdom. I don’t believe it’s unfair to say that it wasn’t until his long-term recording contract with Philips Records got underway, beginning in the early sixties, that he began to have a following in the United States. The series of Berlioz recordings with the London Symphony Orchestra climaxed at the end of the decade in the first complete recording of Les Troyens, which garnered universal raves and won a Grammy in 1971 for best opera recording. Together with his 1966 Messiah, this Berlioz established him over here as a force to be reckoned with.

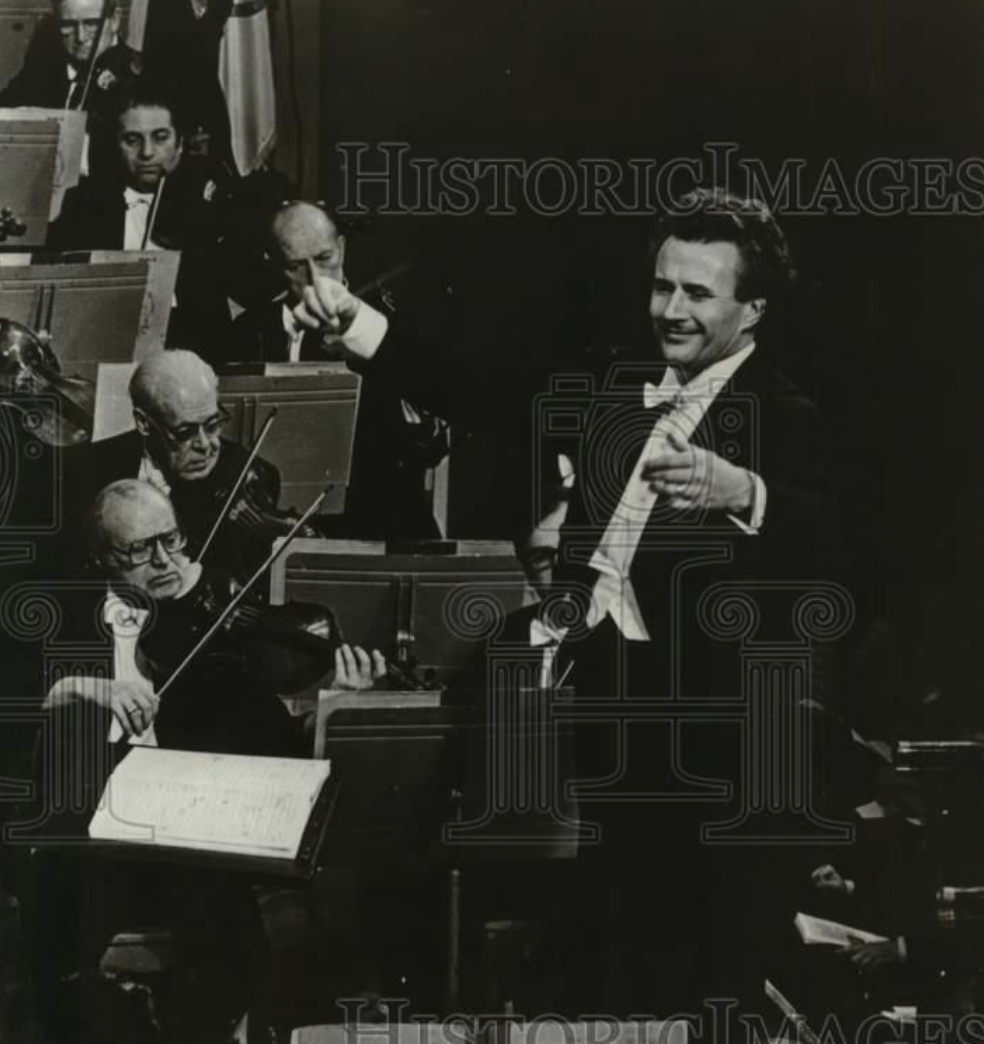

Sir Colin Davis leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra around the time these recordings were made

Sir Colin Davis leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra around the time these recordings were made

That Messiah is the first recording of Handel’s oratorio on a major label by a mainstream conductor and orchestra to observe HIP—Historically Informed Performance—practices. In the decades since, HIP practice, including the use of period instruments, has become so widespread this recording now sounds less adventurous, less sheerly exciting, even a little dated, but this does not matter: it remains one of the great Messiahs in the catalogues, not least because it mediates so perfectly between the latest HIP versions that may be too lean and mean for some and the old-fashioned ones with large forces too plush, lush, and heavy laden for others.

Despite sporadic appearances with major American orchestras during these years, Davis had still not as yet established a real beachhead in the states. He was three times offered principal conductor positions at the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and the Cleveland Symphony and three times refused because he felt his allegiance should remain properly with his native land. But in 1972 he accepted the post of Principal Guest Conductor in Boston, a position he occupied until 1984. There was instant chemistry between the Brit conductor and the American players. In January 1975, following triumphant concert performances, he recorded Sibelius’s Fifth and Seventh symphonies. I do not know if he, Boston, and Philips had planned a complete cycle from the outset or whether it owed to the additional rave reviews that greeted the recording, but over the next two years they recorded the rest of the numbered ones plus a few tone poems, which were released individually over five LPs and as a boxed set in 1977. As with the Berlioz and Messiah, these recordings, greeted with hats-in-the-air enthusiasm, made history, shooting to the top of most of lists of recommended Sibelius symphony cycles. It is arguably these recordings that for American audiences finally ushered Davis into the uppermost echelon of conductors living at the time and helped cement his international reputation.

Decca Pure Analogue: Performances and Sonics

The first to be released was the Fifth and Seventh, offered here in this newly remixed and remastered vinyl release that is part of the Universal Music Group’s (UMG) new counterpart to DG’s Original Source Series vinyl: Decca Pure Analogue. For a fuller background to this series I refer you to my colleague Mark Ward’s announcement in Tracking Angle. The album has been mixed and cut directly from the original ½-inch edited four-track quadraphonic master tapes by the great team of Rainer Maillard, Analogue Mastering Engineer, and Sidney C. Meyer, Vinyl Cutting Engineer, at Emile Berliner Studios. The chain is one hundred percent pure analogue straight to the cutting lathe, with absolutely no intervening processing, compression, or equalization* (Rainer Maillard emailed a correction to this, please see bottom of piece_ed). For a behind-the-curtains peak into the laboratory where these two wizards work their magic, in my view virtually without peer.

In this video engineers Maillard and Meyer work their remastering and disc-cutting magic

Why is a Philips album one of the first three releases? In the late nineties the Universal Music Group acquired DG and Decca, merging the latter with Philips, which they had also acquired, thus explaining why Philips titles rereleased since the merger appear under the Decca label. This particular coupling was recorded in quadraphonic sound, which was all the rage in the early seventies, and many recordings at DG, Decca, and Philips were recorded that way, simultaneously with two channel as well. Unfortunately, owing to poor marketing, competing formats, and consumer indifference, quad never got off the ground, especially with classical music listeners (it still hasn’t), and the labels who were pushing it (CBS, DG, Decca, Philips, EMI, and Vanguard) got off the bandwagon in about as big hurry as they got on it. Philips released only one quadraphonic LP, which sold so poorly the label never released another, and they abandoned quadraphony for the remaining Davis/Boston symphonies. However, what nobody back then foresaw is that one day those back channels would prove transformative for improving the two-channel sound of the same recordings. I’ll return to this later.

These performances have not only never been out of print but have also been released and re-released in various combinations and formats, including compact disc and streaming, which therefore also means they have been reviewed again and again and again the world over, so there is very left new to say about them that hasn’t already been said. So take the remarks that follow as some observations culled from half a century owning and listening to these performances, including several of the CD and streaming versions. to wit: One, these are great performances. Two, Davis gets the quintessential Sibelius sound to a T: dark ma non troppo; cold where appropriate but not frigid or analytical; warm where appropriate but a northern warmth; beautifully layered textures; prominent, characterful winds; weighty yet sonorous brass; horns on the cool side that yet when called for open out to evoke great vistas; brooding cellos and double basses against shimmering violas and violins. Three, Davis always mediates between a certain classical restraint and generous romantic ardor, which is another way of saying between structural discipline and great emotional involvement. Nothing here is self-regarding or attention-grabbing, yet there’s scarcely an indifferent bar and everything moves according to its own internal logic and temperament.

The opening of the Fifth begins so easily and naturally, floating horns evoking distant vistas, rolling tympani welling up from below, followed soon by plaintive winds in the foreground, with absolutely no sense of coercion from the podium as it builds to the first great climax. The next rotation, which resembles a kind of second exposition with new keys and a richer textures, and the next rotation after that, with more complex variations, increased intensity, and quicker tempos, develop as if entirely on their own volition—the bassoons really eerie here—the second rotation evolving inevitably out of the first up to the still bigger third that precedes the scherzo. The transition to the scherzo and its increasing acceleration is tremendously exciting, rivalling even Bernstein’s peerless headlong thrust to the end (Sony). Speaking of this coda, how gratifying to hear the tympani so strong, forcible, superbly registered!

The Andante/Allegretto variations are taken at a welcomely extrovert clip sets up the third movement fittingly. All praise to Maillard and Meyer for cutting the disc master so that the last movement follows attacca with scarcely a second’s pause—in truth, I could take it even shorter, but this is close enough. Once you hear it this way you will never be satisfied with any recording that doesn’t do likewise.

Davis begins the finale’s string tremolos at a so whiplash a tempo that the great theme really is more suggestive of Thor swinging his hammer (on an unusually vigorous day) than sixteen swans in graceful flight, and I feared he would never be able to slow things down enough so that the coda gets its full quota of grandeur. But the way he gradually broadens the tempo over the long span to the Largamente assai is so surely managed that the closing pages are gloriously satisfying, the pauses separating the final six chords spaced, placed, and timed to perfection.

One of the things I’ve always loved about this set is that Davis is unafraid to the unleash the full power of the Boston Symphony, who play like Gods, and he does so in this Seventh. I’ve read at least one review that refers to it as a slog. Seriously? The overall timing is shy of 22 minutes, thus within the 20-22-minute range suggested by the score. I grant I’ve heard more incisive and dramatic performances, but few in the strictly tonal sense that sound richer or more sheerly beautiful. And again I really like his refusal to hasten things forward, as if afraid the piece will drag. When that first big crescendo arrives around 5.5 minutes in, it crests with requisite weight yet not so much as to leave insufficient room for more and bigger down the road. Yet when the section comes that many liken to a scherzo movement, Davis is as animatedly quicksilver as you could want. Control of dynamics and shifts in tempo likewise benefit from his “whatever is best administered is best” approach. This is a deeply satisfying performance with that final perfect C-major cadence so ravishingly played it glows like burnished gold—once you lift the needle, you want to linger there, savoring it.

As Tapiola was for a long time the hardest of the Sibelian nuts for me to crack, I was happy to find it included in this set so I could wrestle with it again. The Wikipedia article on the piece lists the timings of forty-nine recordings from a low of just under 14 minutes to a high of just over 21, leaving Davis’s 18 just about close to ideal. Two things struck me this time: First, I liked it a whole more than before (perhaps because of the research I did preparing this review). Second, something Stravinksy said of The Rite of Spring struck me as applying uncannily to Tapiola: “There are simply no regions for soul-searching.” There is something almost frighteningly elemental at the core of this score that resists too personal an approach. If the Russian’s world in The Rite is primitive, the Finn’s in Tapiola feels positively prehistoric, no place for any sort or primate. Davis’s performance is stark, severe, and incisive, strings chill and shrill, winds bracing and keening, brass piercing and slashing, a striking contrast to the warmth and glow of the Seventh, its flip-side discmate.

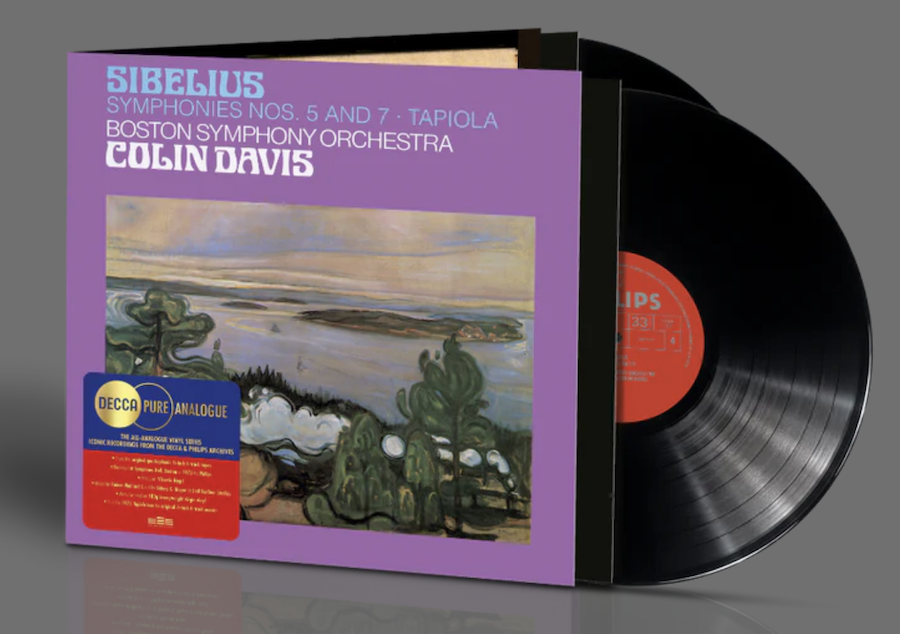

Adorning the covers with a painting each by Edvard Munch was the signature look Philips gave to Davis’s Sibelius recordings.

Adorning the covers with a painting each by Edvard Munch was the signature look Philips gave to Davis’s Sibelius recordings.

The original LP contained the two symphonies only, one per side. But since sound quality is an A-list priority here and in the Original Source counterpart at DG, we must all rejoice in the decision to release this as a two-LP set, the Fifth now occupying two sides of the first LP. Inasmuch as the Seventh fits comfortably onto one side, the people at Decca put Tapiola on the other side of the second LP. Since the tone poem had also been recorded quadraphonically, sonic consistency is preserved.

And How Does It All Sound?

Best to answer that by way of the vintage Philips’s LP. Back in the day the label was one of the premier classical music labels with a roster of artists that would be the envy any A&R executive. No one released a classier product than Philips, and only a few others approached them in that regard: elegant covers, excellent notes, pressings that in my experience were consistently way better than most other labels’. The sound was rarely audiophile spectacular—you got the impression Philips might have regarded that as vulgar—but consistently and reliably it always served the music and the performers with highest excellence. In your face detail was eschewed in favor of a perspective that was more natural and musical. Not distant, mind you, merely slightly set back so that there was some space between you and the musicians. This also had the entirely salutary effect of making their recordings exceptionally truthful to the sound and timbre of real instruments. Tonal balance was rarely bright, almost never edgy, instead warm, inviting, even lovely (dip into the Quartetto Italiano’s recordings some time or Arthur Grumiaux’s Third and Fifth Mozart concertos, conducted by Davis, which has sonic brilliance and sonic warmth in equal measure). I can’t remember a Philips recording that was ever fatiguing to listen to. A vintage copy of the original LP has all these virtues sufficient enough to convey a substantial measure of the scale and power of these scores.

The Decca Pure Analogue version of these recordings preserves and improves, often substantially, upon all the virtues I’ve just described while adding several new ones. For one, a big increase in clarity and transparency, as if a few veils have been removed. Allied to this an equally substantial improvement in dynamic range and distortion, particularly at the ends of sides where loud climaxes typically occur, thus vindicating the decision to split the Fifth over two sides, which allowed Meyer to cut the lacquers stopping a good deal short of the label. Of course, not to be minimized is her cutting expertise: this is some of the cleanest big orchestral sound I’ve heard on vinyl.

The soundstage is very wide and appropriately deep (listen to trumpets in any of the climactic passages), and the entire presentation seems to occupy a vastly more open and expansive space, with lots of air and atmosphere. That tells us why no previous release of these recordings will ever equal the sound quality of this new one in those areas: thanks to the remastering chain Maillard engineered at Berliner Studios, which allows him to mix and balance on the fly directly to the cutting lathe, he was able judiciously to mix the original back-channel tapes into a new stereo master that puts all previous versions in the pale. The effect is revelatory, with considerably more sense of air, space, and separation among the orchestra; several digital releases I spot-checked, while good, sound comparatively congested and in some difficult-to-define sense “smaller,” closed in.

These are not matters of mere audiophile interest, rather are central to the music. For example, those six chords that end the Fifth need to resound in a space that is felt as a real space, and we need to hear them resonate and die away after they’ve sounded before the next one comes in, much as we would in a live concert. The renowned acoustics of Boston’s Symphony Hall constitute a perfect venue for music like this, and it is here reproduced as in no previous version of these recordings. This is spectacular sound so completely in the service of the music and musicmaking that the reproduction never draws your attention from them to it (unless of course you direct your attention to it). In this sense, it is vintage Philips sound brought fabulously up to date.

Finally, I’m happy to report the 180-gram surfaces are pristine, which I hope augers well for the future, because DG’s Original Source Series releases have been very spotty in this regard (a different pressing plant was used). The packaging is substantial, a good weight of cardboard for the gatefold jacket, the original cover with the Edvard Munch painting excellently reproduced, the original liner notes by the always informative Jack Diether on the back, and an insert with a new essay on the background of the recording (a plea to DG: start doing this with the Original Source Series).

A hale and hearty welcome, then, to this new Decca series, with fingers crossed they continue to raid the Philips’s catalogue. In the meantime, I predict this 3000 copies of the first run of this set will sell out in weeks, maybe days, so do not tarry. Fifty years on the vitality of these performances remains as undiminished as when brand new, and thanks to Maillard and Meyer they have state-of-the-art sound.

Further Listening and Reading

There are now so many really excellent recorded performances of Sibelius’s music in good or better sound, it’s hard to go wrong, and I’ve not even begun to explore them as much as I would like. The best guide I know is David Hurwitz and his videos on his Classics Today website. A trained percussionist who has performed a lot of the music he reviews, he seems to have heard practically every Sibelius recording ever made and is able to recall them in detail at will without notes. He’s made video surveys of each of the symphonies, prefaced by discussions of the works themselves that by turns instruct and delight, and at least one survey of complete sets. Here are links to the Fifth the Seventh and the complete sets. I’ve rarely been disappointed by a recommendation of his, to wit: right now I’m investigating the Leif Segerstam big box of Sibelius with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (Ondine), including all the symphonies, and it’s every bit the “great stuff” Hurwitz claims for it.

Hurwitz has also written Sibelius Orchestral Works: An Owner's Manual (Unlocking the Masters) (Amadeus 2007), a book that manages to pack a synoptic view of the subject —placing Sibelius and his music against the symphony as it developed throughout the nineteenth century, other Finnish composers, contemporaries, and pithy but edifying discussions of aspects his art and appreciations of some eighty works—into a remarkably compact volume that is accessible without being superficial.

Robert Layton’s Sibelius, part of Schirmer’s Music Master Series (1965; fourth editon1992) is a comprehensive critical study of great depth and detail that also incorporates considerations of the critical and scholarly literature on the composer, including the reception of his works. There is a detailed chronology of the life and music and a complete list of the works. When I listen to Sibelius’s music both of these books are frequent companions.

James Hepokoski’s Sibelius: Symphony No. 5 (Cambridge University Press 1993), is a really deep dive into the symphony that shows how Sibelius composed it, formally analyzes it, relates it to avant-garde music contemporary with it, and, unusual in book that originates in the academy, concludes by comparing several different recordings in terms of the composer’s prescribed tempos (Kajanus, Karajan/Berlin/1965, Maazel/Vienna, Davis/Boston, and Bernstein/Vienna). A Sibelius specialist, Hepokoski is a distinguished musicologist who co-authored a groundbreaking theoretical study that developed a new way of approaching sonata form. As you might expect, his Sibelius book is highly technical, headily theoretical in places, and closely, indeed densely argued. Please do not let these observations scare you, for this a superb book, written with great clarity, from which I learned a lot about Sibelius himself, this particular symphony, and much else.

A really good short essay on Sibelius that could also serve as an introduction is the chapter in Alex Ross’s The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2007), a book that is well worth reading for many other reasons as well.

From Rainer Maillard, who offers the following corrections to my statement regarding what is in the mastering chain for both Decca Pure Analogue and DG’s Original Source Series. I wish to thank Rainer for giving me permission to reprint his email setting the record straight and to apologize for my mistake—at least I got the pure analogue part right! By the way, he has the highest respect for the original recordings, as do I. His email is here quoted in full:

Dear Paul,

Thank you for your very interesting article in TrackingAngle. And thank you for viewing the work of Emil Berliner Studios so positively. I am very impressed and delighted.

I don't want to be pedantic, but I would like to add a few little thoughts on the following sentence:

“The chain is one hundred percent pure analog straight to the cutting lathe, withabsolutely no intervening processing, compression, or equalization.”

Is this statement accurate?

Equalization: On its way from the tape head to the cutter head, the signal usually passes through four analogue filters:

First, the CCIR or NAB recording curve is compensated for in the tape machine.

Then, there is usually a filter in the mastering chain that individually adjustments make possible. There can be many different reasons why this may be necessary.

The signal then passes through the RIAA recording filter, followed by another filter that adjusts the individual characteristics of the cutting head.

Four filters in the signal path! To my opinion it is not a question of having EQ in the chain, it is a question how to use them correctly.

Compression: Considerations regarding dynamics are even more complex: even the position of the listener in the concert hall (or the position of a single microphone) influences the dynamics. It is impossible to determine what the original dynamics in a concert hall actually are, because they vary from seat to seat (depending on the directivity of the instruments). Example: Mahler wrote in some places in the score: “Stürzen hoch” (bell rise up). This will be heard different for listeners in the concert hall, depending on their seat, depending on the musicians, depending on the instruments, ….. What is right, what is wrong? The answer depends on many factors, even in a concert hall.

Then we have the sound engineer during the recording, who mixes different microphones together with his fader. Often, however, this process can be described as exaggeration (opposite to compression), because instruments are often raised rather than lowered for additional support. The dynamics on a tape can therefore be higher than what a listener hears in the concert hall. Again: What is the original dynamic of a recording? And is the dynamic on tape is right or wrong?

Another consideration: our ear is not a linear system, which means that we perceive dynamics differently depending on the absolute volume. If we listen to a record at a lower volume than the composition in the concert hall, we perceive the dynamics incorrectly. So this is quite a complex structure. The mixing engineers have to translate for the listener without knowing, how they would listen to a record at home. Which (individual) volume deliverers the right dynamic for the listener? (In the cinema/movie-world, this problem is fixed, because the listener is not free to change the volume individual.)

Conclusion: for the Decca releases, we mixed with further dynamic treatments (and EQ) by our taste. In each case with different solutions. Sometimes we made passages or instruments louder, sometimes quieter. Sometimes we raised frequencies, sometimes we lowered them.

I'm glad that this gave the impression that no compressor or equalizer was used. But the opposite is true.

Best regards

Rainer

Notes

[1] It was only when the four works, revised and reordered, were published together as a suite in 1954 did Sibelius title it Lemminkäinen.

[2] If you follow this line of reasoning and number Kullervo and Lemminkäinen as symphonies and do the same with Tapiola, then the tone poem becomes number ten and the symphony he worked on in his later years an unfinished eleventh!

[3] Sibelius’s statement is not completely accurate, but it is true enough that its currency continues unabated even if the majority of people who quote it are almost certainly ignorant of who said it first.

[4] Sibelius and his drinking cronies called themselves “The Symposium.” It is reported they often played a game in which after consuming a certain quantity of alcohol, one of them would be chosen to go into a closet and after about fifteen minutes would be required, without leaving the closet, to name everyone he had drunk with throughout the evening. If he couldn’t or said nothing, it was assumed that he was too drunk to continue drinking or had passed out. Rumor has it that a journalist once asked Sibelius if this game could be played by a pair of drinkers. The composer replied that it could but it would take a great deal more vodka.

[5] Critics like Adorno, Thomson, and Leibowitz were outliers when it came to the reception of Sibelius’s music, which cast a long and strong shadow of influence that continues to the present day. In addition to numerous Scandinavians such as Allan Pettersson, Wilhelm Stenhammar, and Joonas Kokkonen, he was greatly admired by several important British and American composers, including Ralph Vaughn-Williams, Arnold Bax, Michael Tippett, William Walton (the opening of whose First Symphony evokes the sound world of the Fifth), Howard Hanson (who wrote a single-movement symphony), and Roy Harris (who wrote two). Benjamin Britten credited Sibelius with luring him away from the avant-garde Second Viennese School that claimed his attention early on. Among contemporary composers who’ve acknowledged Sibelius’s influence are the minimalist or minimalist-adjacent John Adams, Philip Glass, and Thomas Adès. And where would the world of film music, notably big spectacle-type movies, be without Sibelius? John Williams, John Powell, Bernard Herrmann, and Michael Kamen (who actually used Sibelius’s music in a Die Hard movie and The Dead Zone) have all acknowledged their debts. At least one critic has called attention to a similarity between the theme of the first movement of Sibelius’s First Symphony and the Monty Norman-John Barry James Bond theme, while Alex Ross, The New Yorker music critic, has pointed out that in the opening of the Fifth and the opening of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme “the sequence of intervals is the same: fourth, major second, fourth again” (though he believes the Coltrane influence comes by way of Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town, which uses the same figuration).

[6] Robert Layton, The Master Musicians: Sibelius. Rev Ed. (New York: Schirmer Books, Macmillan, 1965, 1992).

[7] Cities are not natural phenomena, but if we were to add cityscapes, several pieces by Varese, Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, and Bernstein’s Fancy Free, not to mention most of the instrumental pieces from West Side Story, could easily find a home in this company.

[8] James A. Hepokoski. Sibelius: Sibelius Symphony No. 5. Cambridge Music Handbooks. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[9] Before I had read much critical commentary on the Fifth, I thought the arch metaphor was my own personal perception. Alas no. Hepokoski’s book quotes a critical study by Lionel Pike, a British organist and professor at the University of London: “The overall plan of the symphony is an arch—the tempo of the opening movement changes from slow to fast, the second movement combines the two speeds in counterpoint (and at one point in heterophony), and the Finale stars with fast music but ends slowly” (78; 131 in Pike’s book: Beethoven, Sibelius, and “Profound Logic”: Studies in Symphonic Analysis [London: The Athlone Press, 1978]).

.jpeg)

.png)