Daniel Barenboim Conducts Bruckner's "Romantic" Symphony

A riveting performance from the orchestra and from the grooves

Anton Bruckner’s (1824-1896) Symphony No. 4 in E-flat Major, premiered in 1881, is the composer’s most popular “early” symphony, with numbers 7, 8, and the incomplete 9 being the usual headline works. It was also his first major success as a composer, before which Bruckner's renown was mostly as an organist and counterpoint instructor. Bruckner dedicated this work to Austro-Hungarian royal, Prince Konstantin, who was a major financier of cultural life in Vienna during the time. The subtitle “Romantic” was the composer’s own, and for him it referred to a mythical past of the medieval era. In fact, he left a written program note of the opening movement I. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell:

“Medieval city—Daybreak—Morning calls sound from the city towers—the gates open—On proud horses the knights burst out into the open, the magic of nature envelops them—forest murmurs—bird song—and so the Romantic picture develops further…”

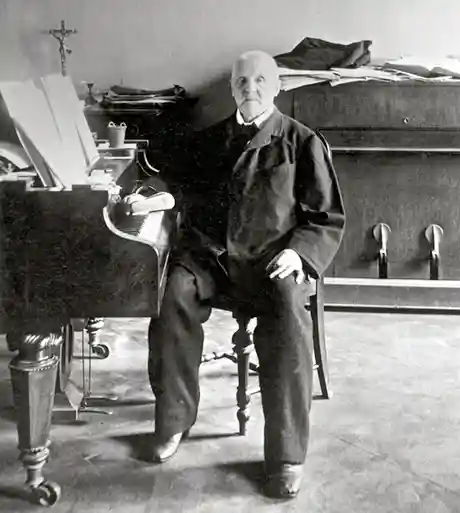

The composer at the piano in 1896, shortly before his death

The composer at the piano in 1896, shortly before his death

There is also a persistent birdsong throughout this movement modeled after that of the European Great Tit (that’s actually the name of the bird, I’m not making that up). In that respect, Bruckner shares a commonality with Ottorino Respighi, another composer of epic orchestral works.

The second movement has a subdued solemnity to it, and like most of Bruckner's thematic material is quasi-religious, as he was a deeply devoted Catholic. The third movement is an energetic hunting Scherzo filled with brass calls through the woods. The final movement, the Finale, really makes this symphony a great work of Wagnarian romanticism. First, it’s a minor key finale in a major key symphony; but also Bruckner never gave it a subtitle (although he apparently scratched out several attempts, none of which seem particularly related). This brings to the music both an air of mystery and also gravitas, which, compared to the previous material, is quite foreboding.

This symphony has numerous versions and revisions, but the “standard version,” the one Bruckner premiered, the one most often played, and the one featured on this recording, is the 1880 edition. This might be confusing because the back jacket states “Original Version: Robert Haas”, but that refers to editor Robert Haas’s restoration of Bruckner’s 1880 version not the one from 1888 (which includes many superfluous edits by the publisher), and not the composer's 1874 manuscript. The composer shelved and never intended for that manuscript to see the light of day, though it has subsequently been published by Bruckner obsessives and contains completely different 3rd and 4th movements. Does that all make sense? No? Well for the purposes of enjoying this majestic and haunting symphony, it doesn’t matter all that much.

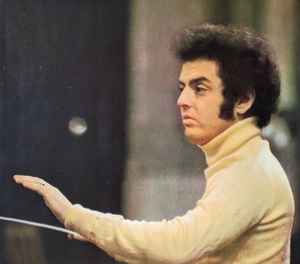

Daniel Barenboim was only 30 years old when he recorded this monumental work with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. His rise to fame was primarily as a young prodigy pianist, making many recordings and touring the globe, although he studied conducting at a young age with the great Wilhelm Furtwängler, who remained an artistic influence throughout his life. He made his conducting debut in 1966 at the age of 24, so the maestro made this recording a mere six years into his career on the podium. Despite that, it has made a lasting impression.

Why? Because this is one of the most ferocious, energetic performances of any Bruckner work on record. Barenboim drives the orchestra forward and lets them do what they do best, play, and play loud. In 1972 the Chicago Symphony had one of the best wind sections in the world. The brass players in particular were legendary, and remain so to this day, with the likes of principal trumpet Adolf “Bud” Herseth and principal horn Dale Clevenger spoken about reverentially by today's brass players. Between them and their colleagues, from the days of Fritz Reiner right up until Barenboim returned to take the music directorship in 1991, this orchestra was known for their its sound cultivated primarily by the Chicago Symphony brass—one of resonance, clarity, precision, and most notably, power. This reputation partly explains why the orchestra's performances of large orchestral works such as those of Mahler, Strauss, Wagner, and yes, Bruckner are so revered. Herserth and the CSO trumpet section

Herserth and the CSO trumpet section

And in this rendition, boy does the group live up to its reputation. Barenboim brings the energy and the enthusiasm as a young firebrand at the start of his career, and the Chicago Symphony bring a finesse and power that few other orchestras at the time could match, especially for this repertoire. If you want to hear the finest brass players of the 20th century screaming at their maximum power, this performance delivers. Are there more contemplative, solemn, recordings of Bruckner 4 also worth your consideration? Sure, Eugen Jochum recorded the complete cycle of symphonies twice, once on DG (104 929/39) and once for EMI (1C 127-54 234/44), and both sets are superb. There’s also a fantastic reading on Columbia/EMI by Otto Klemperer (SAX 2569) reissued AAA relatively recently by Hi-Q records (HIQLP 057), and those are more “traditional” (often slower) interpretations. The kind where there is a water-like churning of sound that washes over the listener (and many people love Bruckner for that effect). But for me, this Barenboim recording gives the work the necessary vitality to inspire the listener, and it has now become my go-to recording. Rather than leaving you contemplative, it leaves you awestruck.

How does the new EBS cut sound? In short: a triumph. First of all, Rainer and Sidney made the right call by splitting this record onto 4 sides. The original 1973 single-LP edition is a hopeless mess from cramming 64 minutes of music on one disc! And that’s with all the compression and limiting used in the original mastering. Giving this recording the dynamic room to breathe was the first hint of success, with none of the scary inner-groove moments that have plagued some of these Original Source releases over the last year. This recording, done right across the street from the Symphony Center at Medinah Temple (where much of Georg Solti’s CSO Decca recordings were done) is rich, clear, and powerful.  Medinah Temple, where many Chicago Symphony recordings were made in the 1970s and 80s

Medinah Temple, where many Chicago Symphony recordings were made in the 1970s and 80s

I heard no distortion in my copy, which seems well-mixed and mastered from DG's original 4-track tape. Perhaps either with or without my complaints, EBS has learned its lesson from the oversaturated cuts of the Brahms Piano Concertos. Even the dreaded "glassy" DG string tone that I’ve complained about often is mostly absent, instead we get to hear the fine and colorful contributions of the orchestral musicians, spread across a deep soundstage. This is one to wake up the neighbors, and it’s simply one of the best sounding Original Source titles I’ve heard so far. The combination of riveting performance, glorious sonics, and interesting if not outright underappreciated repertoire (let’s face it, Bruckner has his devotees, but not the wide recognition of Mahler or Wagner) makes it an easy recommendation. If you are on the fence about which of these four new titles is a “must-buy”, this is the one. With this cut, Bud Herseth is in your living room.

.png)