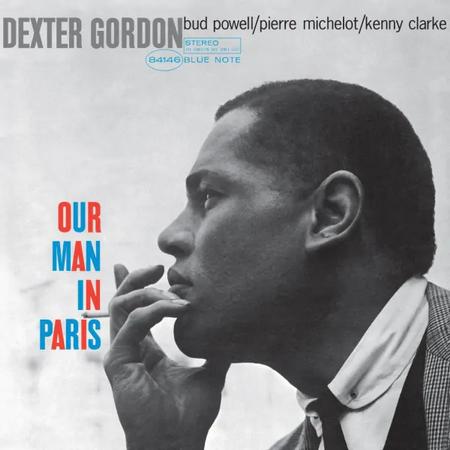

Dexter Gordon in Paris

The sultry tenor sax giant's first adventure as an exile

Dexter Gordon was a striking figure—6’6” (one of his albums was called Long Tall Dexter), with a dry wit, a voice as foggily husky as his tenor saxophone tone, and (as an iconic photo taken by Herman Leonard reveals), lungs capacious enough to hold what looks like an entire cigarette’s worth of smoke in one breath. (This last trademark-feature led to his death from emphysema in 1990 at age 67.)

In his last decade, Gordon became a true star, owing to a celebrated return to the states from a 14-year self-exile in Europe and to his lead part in Bernard Tavernier’s Round Midnight, where he played a legendary American jazzman in Paris. (The film had problems, as did Gordon’s saxophone playing at the time, as he was in poor health; but his screen performance was terrific, landing him a well-deserved Oscar nomination for Best Actor.)

What sometimes went missing from these autumnal accolades was an appreciation for his earlier role, as a vital transition figure, in modern jazz. He synthesized the influences of the mid-20th century’s two major tenor saxmen, Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins—a challenging task, as the pair led antipodal movements, Young stressing a fleet melodicism, Hawkins extending chordal improvisations with a thick tone—and navigated this fusion through the syncopated pathways carved by Charlie Parker’s bebop. The resulting sound and style (especially his forward steps in adapting Parker’s innovations on the tenor) influenced, in turn, Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, who molded the shape of tenor-sax jazz through the decades ever since.

Gordon was born and raised in L.A., the son of one of America’s first Black medical doctors. He started playing with big bands in his late teens, moved to New York in 1944 (as bebop was hitting its stride), didn’t stand out much amid the crowd, and, after just two years, returned to the Coast, where he made his mark—and started planting his style—in high-octane jam-session saxophone duels, which he usually won. (The albums he made with fellow tenorman Wardell Gray—The Chase, The Steeplechase, and The Hunt—are key.)

He vanished from the scene for most of the 1950s, spending much of the decade in jail on drug charges. He kicked his heroin habit during his final incarceration, at Folsom State Prison, got out in 1959, and, two years later, signed a contract with Blue Note. It was there that he started stretching out in song forms, often quoting snippets from other songs within songs—standards and originals—and developing a seductive way with ballads. The British critic Alan Beckett referred to his “gruff lyricism.”

Once re-emergent, he got off to a brisk start. His first two albums for the label, Doin’ Alright and Dexter Calling, were recorded over the space of three days in May 1961. His third, Go!, widely seen as his best, was laid down a year later. Then, like many African-American jazz musicians who felt more appreciated and less oppressed on tours abroad, Gordon moved to Europe—first to Paris, then to Copenhagen.

Our Man in Paris—recorded in 1963 and recently reissued on LP as part of Blue Note’s Classic Vinyl series—was the first of four albums he made for the label from his new digs before decamping two years later to Prestige (for which he cut many albums during trips back to the US), then to the Danish label SteepleChase.

As on many of his subsequent European albums, he played not with a regular band but with a mix of prominent Americans (some visitors, some fellow exiles) and less-well-known but more-than-competent locals—in this case (one of the more star-studded sessions), Bud Powell on piano, Kenny Clarke on drums, and Pierre Michelot (a staple of these trans-Atlantic dates) on bass.

Story has it that Gordon had planned to record an album of all new compositions with Kenny Drew on piano. When Powell—perhaps second only to Monk as the most innovative modern jazz pianist—became available, he pushed Drew off to a later session. But it turned out Powell didn’t want to play new tunes, so Gordon reverted to a litany of bop classics (Parker’s “Scrapple from the Apple” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night in Tunisia”) and standards (“Willow Weep for Me,” “Broadway,” and “Stairway to the Stars”).

In this sense, Our Man in Paris is often tagged the last bebop album: bop songs played in a bop style by bop pioneers at a time when the music was still modern—encased somewhat in amber, especially in the context of the free jazz that many of their contemporaries were exploring (notably Rollins, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane), but not yet nostalgic.

It's not my favorite Dexter on Blue Note—I prefer his looser, livelier, slightly more experimental albums, especially the first three New York dates, where he’s egged on by younger sidemen, such as Freddie Hubbard, Sonny Clark, and Billy Higgins, who were moving on from their bop roots. Still, Our Man is an indisputably great album, even if it’s a bit self-consciously so, and Gordon is in near peak form, approaching the old tunes with zesty adventure, probing sinuous back alleyways, sometimes carving whole new paths alongside, or burrowing deeply into, familiar territory. And the album’s one ballad, “Willow Weep for Me,” is just gorgeous.

That said, the rhythm section doesn’t dazzle. I remember buying a reissue of this album in the late 1970s, when I was just getting into jazz, wide-eyed at the cast. (Who knew—I didn’t—that Dexter Gordon had recorded a session with Kenny Clarke and, especially, Bud Powell!) I was disappointed that they sounded like members of a fairly routine pick-up band (except on “Willow,” where Powell steps out with a scintillating solo). Many years later, listening to a better pressing on a much better stereo, I don’t feel much different.

Part of the problem may be Powell, who had famously gone through many mental difficulties, exacerbated by drug and alcohol abuse and a severe police-beating 20 years earlier, and who, though living a better life in Paris, was still not in good shape. (He died from tuberculosis and malnutrition three years later, back in New York, at the age of 41).

But part of the problem may be the set-up. Rudy Van Gelder, who had long defined “the Blue Note sound,” wasn’t flown to Paris to record this session. Helming the controls instead was a local engineer, Claude Ermelin, who, judging from my Google search, worked more on movies than jazz albums, though many years later, he recorded the soundtrack for Round Midnight. In any case, on Our Man, the musicians sound pretty good when they take their solos, but when they play together, the mix is a bit muddy. Often you can barely hear Powell. (Capturing pianos wasn’t Van Gelder’s strongpoint either, but, compared with this display, they sound vibrant on slightly earlier Gordon sessions at RVG’s studio in Englewood Cliffs.) The drumkit is a bit blanketed as well. On the other hand, the bass sounds consistently clear and thumpy. Gordon’s sax is up front, and his tone properly foggy, though there’s not much dimension; it’s as if the top octave is veiled.

I also wonder if the original tapes might have decayed in the last decade or so. An earlier reissue, by Music Matters Jazz, mastered in 45rpm back in 2012, sounds a bit brighter (in a good way), though, again, not up to the standards of an early-‘60s Blue Note. (If I were reviewing it now, I’d give the MMJ an 8 for Sound.)

Still, this is an immensely pleasurable album, one for the ages.

Here's a Dexter Gordon documentary:

.png)