Fillmore Street Little Woodstar

Composer Sasha Matson's latest album contains a new piece and an early one, substantially revised (includes interviews with producers John Atkinson and Joe Harley)

Sasha Matson Conducts his Latest Works Combining Jazz and Contemporary Classical

Sasha Matson Conducts his Latest Works Combining Jazz and Contemporary Classical

Sasha Matson will be a name known to many audiophiles through his previous recordings for Audioquest, New Albion, Albany/Troy, and Stereophile. That they all are for labels with an audiophile orientation or association comes as no surprise inasmuch as he has written for Positive Feedback and is currently a Contributing Editor to Stereophile, where he writes about music and sound. He graduated in composition from the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he was mentored by the composers Elinor Armer, John Adams, and Andrew Imbrie. Later, he received a PhD in Musical Composition and Theory from UCLA, and he has taught at LaGrange College, Long Island University, and The State University of New York.

With a background like that you might think Matson writes only so-called “serious music” of a classical bent, but in fact he embraces music across many genres and styles, the result being compositions that draw on a considerable variety of sources and inspirations, including classical, romantic, neo-classical, pop, rock, folk, and jazz, involving quite a lot of cross-pollination. His last album, for example, Molto Molto, is jazz, yet the pieces are cast in classical forms such as symphony and concerto. His new album consists in two separate pieces, Fillmore Street and Little Woodstar— the album’s title runs them together sans conjunctive—for which he employs, and conducts, two sixteen-piece ensembles: a “jazz orchestra,” to which he adds a Moog synthesizer, in Fillmore; and a “studio orchestra,” to which he adds a vocal quintet, in Woodstar. Other differences include a full string quartet, harp, and piccolo in the studio orchestra; a greater complement of brass and saxophones, but no cello, second violin, viola, harp, or piccolo for the jazz orchestra. The extraordinary color and variety he secures from each ensemble are pleasures in and of themselves, especially when captured as colorfully and as vividly as they are in these recordings.

Matson is a professional composer who works in the commercial sphere (around a dozen film scores, for example); but he is also a personal composer, by which I mean that much of his work, and certainly the pieces I am most familiar with (i.e., his last four albums), was and is written for no other reason than that a composer is what he is and writing music is what he must do, out of inner as opposed to outer necessity (not that the two, as with most composers, do not overlap). Both pieces here grow out of his love of nature, including people and places, and his commitment to ecological issues such as climate change, global warming, and endangered species.

Fillmore Street

Composed in 2023, Fillmore Street is a three-movement suite that evokes California places of personal significance to him. The first movement, which duplicates the title of the whole work, recalls the famous street (named after the president Millard Fillmore) in the City by the Bay that goes from the Haight through the Fillmore District to Pacific Heights and the Marina District and is known for its diversity of people, stores, restaurants, nightclubs, and music. “Sonora Pass,” the next movement, is the second highest pass with a road through it in California, connecting the city of Sonora to the west with the Sierra Nevada Mountains. “Mar Vista” is an area in West Los Angeles, between the 405 Freeway and the Pacific Ocean. For a long time it was one of the undiscovered enclaves on the west side of the city with affordable housing and a diverse community where Matson and his family lived while they were in Southern California.

Musically, the suite, like much of Matson’s other music, is formally and stylistically eclectic. “Fillmore” itself is in three sections, the first section opening at a moderate tempo that is nevertheless very propulsive (with pushed rhythms), instruments added until it crescendos with an abrupt cut-off, followed attacca by a lyrical section that swings gently on piano, drum set, and bass, eventuating in a beautiful melody carried by the trumpet. The third section again begins attacca with one of the boldest gestures on the album, referencing John Adams’s Shaker Loops, the sleigh bells at the outset of Mahler’s fourth symphony, and the rhythm of Smokey Robinson and The Miracles’s "Going to a Go Go.”

Let me say right off that I identified the Shaker Loops, but not the other two. The winds that imitate the sleigh bells actually reminded me of the way Gershwin suggests car horns in An American in Paris; I don’t know (or else have forgotten) the Robinson song. Matson calls these measures, with no little pride, “a three-way mashup,” and as soon as he mentioned the Mahler, I heard it immediately. Does it matter if one picks up on all references? I don’t think so. It’s obvious that something at once unusual, rather daring, and highly original is going on here, that three things which don’t ordinarily go with one another—symphonic music, extra-musical references, and Motown R&B—are being yoked together to witty, even funny effect. It certainly made me smile. The triple allusion, by the way, stylistically reinforces the theme of diversity that courses through the album (the song itself, according to the critic John Bush, “ignited a nationwide fad for go-go music”).

“Sonora Pass” functions somewhat like an andante or adagio, suggesting the vastness of a mountain vista, the Moog synthesizer sounding subterranean rumblings. “Mar Vista” opens with bongos and bass accompanying the violin, which plays a sinewy theme that suggests music of the night, later joined by trombones and synthesizer. About halfway through there is an interlude where the tenor sax takes over with another beautiful melody that for me evokes the world of postwar Los Angeles as depicted in film noire movies. As night gives way to morning, instruments are added, the tempo accelerates (echoes of The Rite of Spring) to an almost triumphal crescendo that ends with a pair of chords that brings things to an abrupt end (Matson seems to like abrupt disruptions, which he deploys very effectively). They struck me as coming right out of the very end of Mahler’s first symphony—if not literal quotation, then amounting to the same thing in placement and effect. I didn’t ask Matson if this is intentional, not least because it hardly matters. When it comes to works of art, each of us brings his or her own frames of reference and experiences to the table, and artists have only so much control over how we respond or what memories and associations are touched off.[1]

In case I haven’t made my enthusiasm clear, Fillmore Street is an absolute corker of a piece! I’ve listened to it several times, each time with greater enjoyment and delight, discovering something new and fresh, and it’s one I would be happy to hear played in concert. I hope my remarks about stylistic eclecticism, influence, allusion, reference, and quotation are not taken to imply any lack of originality on Matson’s part. Throughout history all composers draw upon music past and present, quoting it, borrowing it, sometimes blatantly stealing it. “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal,” Stravinsky once said.[2] It’s a way of incorporating one’s history, personal and educational, into one’s music and establishing both continuity with and divergence from tradition. Like Leonard Bernstein, Matson is musically erudite with enthusiasms that range far, wide, and deep; and as with Bernstein, whose music for all that may recall other composers nevertheless always sounds like Bernstein himself, nobody else, Matson’s music, however eclectic, is never pastiche, instead fused into a sound and style all his own.

Little Woodstar

Little Woodstar is a different kind of piece. Avid hiker and long-time member of the Sierra Club, Matson draws upon the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s “Red List of Threatened Animals” for inspiration. The vocal quintet intones the names of forty-seven threatened species (an insert lists them in the same sequence as the composition). Written when he was an undergrad for full orchestra (see accompanying interview) and built, by his own admission, on open Coplandesque fourths and fifths, it begins very grave and solemn, with what sounds like a softly played flugelhorn and plaintive winds, the effect almost one of mourning and stasis. It’s not until a voice sings “Little” and other voices join in that a pulse begins to develop; before long an orchestral interlude driven by drum set and brass energizes music. The second movement (of two) also begins quietly, but soon enough a driving rhythm section accompanies the voices who sing in overlapping legato lines while the spare textures become fuller and louder as more instruments are added. It’s remarkable the sense of size Matson manages from a sixteen-piece orchestra and five voices. After rising to a couple of big climaxes, the composition ends softly, the voices allowed to dominate the texture until, accompanied by delicately played bells, they fade into silence.

This is plainly music at once deeply personal and very ambitious that yields its mysteries more reluctantly—or perhaps I should say less immediately—than Fillmore Street. That (as I hear it) mournful opening puts me in mind of a requiem, maybe because the vocal parts are cast in long phrases, by turns drone-like or melismatic, that make it difficult (even when listening with headphones) to discern the names of the animals, except in snatches, a syllable here, a full word there. Little Woodstar, the first name sounded, is a species of hummingbird, yet the first syllable is so stretched out I couldn’t comprehend it even though I knew what the word is supposed to be.[3]Despite the occasional use of the winds to suggest bird song—hey, it was good enough for Beethoven—I found the overall effect melancholic, ruminative, contemplative, introspective, even when Matson marshals all his forces for the big moments, which are either celebratory or declamatory depending on how you hear them (the latter for me). In other words, despite the explicit animal references and the diegetic-like instrumental sounds, Woodstar comes across more as abstract or “pure” music, the consequence being that the celebratory intent, or at least the precise expressive effect of same, is rather obscured. Although the orchestration is quite imaginative and rather wonderful, I found all those open fourths and fifths cool, even chilly, the result being a degree or two of separation from the music, and a feeling that my intellect was more engaged than my emotions. (The fact that it was originally conceived and written for a full orchestra is tantalizing: Might the somewhat objectified effect I experienced function more positively, that is, more powerfully with a larger instrumental contingent and a real chorus?)

Yet I shouldn’t want these observations, many of which are subjective, to suggest I didn’t like Little Woodstar, only that I have yet fully to connect or come to terms with it. Otherwise, it’s a fascinating, haunting (even hypnotic, in places), and thought-provoking piece, obviously deeply felt, with passages of chaste beauty and restrained power. I am far from finished with it. The performers, each and all, are world-class, as are the performances.

Sonics

I must preface the following paragraphs by pointing out that I commenced listening to this album as I always do when evaluating the reproduction of recordings I am reviewing: by not reading any available background information as to how it was done. I like to form my impressions without such foreknowledge. After jotting down my notes, I did incorporate some of the pertinent information from the subsequent interview with the composer and the two producers, as it essentially corroborates my initial notes. I do, however, urge you not to pass up the interview, especially if you've a serious interest in sound.

The two pieces are recorded in different venues: Fillmore in Manhattan’s Sear Sound studios by James Farber, who also did the mixing; the orchestral part of Woodstar in Hollywood’s East/West Studios by Steven Genewick, the vocal quintet back at Sears, by Chris Allen, who also did the final mix. Producing credits are shared by John Atkinson (New York) and Joe Harley (Hollywood). All the technical credits are first class, including the vinyl mastering by Matt Lutthans, vinyl pressing (outstandingly quiet surfaces) by Quality Record Pressings; John Atkinson did the digital mastering. All recording was done in the digital domain (see interview for more on this).

Overall the sonics are excellent in both venues, transparent, clean, clear, everything beautifully registered. Fillmore was recorded in the largest studio at Sear Sound, yet sixteen instruments, several of them brass, not to mention the Moog, sometimes playing at full tilt call attention to the fact that the ceiling is low, so the sound, despite a wide dynamic range, doesn’t open out the way it does in the East/West venue. Notwithstanding the number of microphones—over forty—and their close proximity to the instruments, with the inevitable bleed from one to the other, the gestalt of a body of instruments obtains to a quite remarkable degree. Even the drum set and the double bass, segregated in separate rooms so they wouldn’t overwhelm the other instruments, are mixed, balanced, and placed in the soundstage so as to fool us into thinking they are in the front with the rest of the orchestra. You wouldn’t think an ensemble of sixteen would yield a wide soundstage, but it does to a surprising degree, no doubt because most of the group were in a single line against the wall across the front. Of course, this means there is little or no depth as such (so if your setup doesn’t reproduce it, I’d suspect at bit of lay back in the presence region).

On Woodstar, recorded in a much larger room at East/West with pretty high ceilings, the sound is both more open and has some depth because the ensemble is not in a single row. The vocal quintet, recorded later on the other side of the country and overdubbed, is so convincingly mixed and placed in the soundstage, slightly in front of the orchestra, as to be seamless. Very impressive indeed (see interview for more on this).

The vocal quintet at Sears Sound in New York City.

The vocal quintet at Sears Sound in New York City.

Each of Sasha Matson’s last three albums has represented a fresh departure, likewise this new one. If you’ve a taste for music that is highly original without being idiosyncratic, contemporary without being merely trendy, learned yet not in the least academic, serious even when it’s light and amusing, and entertaining in the very best sense of the word, I urge you to investigate this album.

In late January Sasha Matson, John Atkinson, and Joe Harley joined a Zoom session with me to talk about Fillmore Street Little Woodstar. The following interview draws from the conversation.

Paul Seydor: So let’s start with the music.

Sasha Matson: Little Woodstar is a celebratory environmental statement and one of those pieces that composers sometimes write that they never stop revising. I first wrote it in graduate school at UCLA in the nineties, but I wrote it for a huge orchestra and guess what? I never heard it. But now I get to hear it under my own direction by reducing it down to a sixteen-piece group. And I can sincerely say I like it in one-on-a-part form. This music is challenging for the players. One of the main reasons is that I love wide-open Copland-like harmonies that feature exposed fourths and fifths. If the intonation on these is off, the music is DOA. My longtime concertmaster, Peter Kent, has perfect pitch, and none of that stuff gets by him. The vocal quintet sings proper English names for forty-seven creatures, and led by soprano Aubrey Johnson, they sang them beautifully.

PS: And Fillmore Street, a more recent piece?

SM: It’s scored for the same sized group only in the direction of a jazz orchestra—fewer strings and so on—and it tells musical stories about three locations in California that meant a lot to me: "Fillmore Street," quotes from music that I lived with in the early eighties, while in San Francisco—I actually lived on the street. "Sonora Pass," paints a musical picture of that transcendent area in the Sierra Nevada mountains, enriched by the sound of an early modular Moog Synthesizer owned by the studio SearSound in New York city, where we mixed it. The third movement, "Mar Vista," recalls for me the energy of living in Los Angeles. There are many quick musical changes here, a nod to Frank Zappa, whom I had spent some time with. Frank once told me, "I like music with a lot of little notes in it."

PS: I was curious about the size of the room for Fillmore Street.

SM: It was done at Sear Sound in New York, in Studio C, their biggest room, a rectangle with a few Manhattan columns going through it that make sight lines difficult. We maxed out that room with a sixteen-piece group plus the synthesizer. The group was arranged in a U around me, winds on the left, trumpets in the center, ‘bones [i.e., trombones] on the right, with the piano far left.

Sear Sound Studio C: Note the low ceiling and the ensemble in a single, U-shaped row in front of the composer.

Sear Sound Studio C: Note the low ceiling and the ensemble in a single, U-shaped row in front of the composer.

PS: I found myself wondering why more audiophile-oriented albums don’t print diagrams of the group indicating the position of the various instruments.

JA: Drums and bass were in separate booths.

PS: Is it typical to isolate drums and bass like this?

JA: As Sasha pointed out, Studio C is Sear’s largest room, even so, drums and bass would overwhelm a group this small if placed in a room that small.

SM: My previous album Molto Molto was done in large room with the drums not isolated. But there are issues with that too—everything bleeds into everything else. There were no mikes where you couldn’t hear everybody else.

JA: But in the mix, Sasha, Nicholas Prout arranged it so the bleed came from the right positions in the sound stage. In other words, the bleed didn’t interfere with the positions of the instruments in the soundstage, it actually reinforced it.

SM: But this is not something you could do direct to stereo because James [Farber, the mixer] had forty mikes running here.

PS: You got really nice dynamic range, but it sounds to me as if the ceiling is fairly low.

SM: It does not have a high ceiling, which is something John and I discussed.

PS: So you have close miking and a small room, did you have to add any atmosphere or reverb?

SM: Something I requested was the old spring reverb units, I forget the name—

JH: —EMT is the brand—

SM: —they put them in the walls for isolation.

PS: Please explain how that works?

Joe Harley: It’s on a separate feed and you can dial in as much or as little as you want.

PS: So you can also control any potential phasing issues?

JH: Yes, you can do that, but you want it to be done while they’re playing so that the reverb is tied to the playing.

JA: One thing I wanted to say about Sear Sound is they have a fantastic collection of vintage microphones, some of them from Bob Fine back in the day.

JH: EastWest Studios in Hollywood, where we did the Woodstar orchestra, also has a great collection of microphones—tough to beat too. For me, EastWest and Sear on either coast—they’re the places to be.

East/West Studio: note the larger room, the much higher ceiling, and the different arrangement of the studio orchestra.

East/West Studio: note the larger room, the much higher ceiling, and the different arrangement of the studio orchestra.

PS: Okay, you have a great collection of mikes that allows for virtually complete control of balances and isolated drums and bass that you can place more or less anywhere, so I can’t help wondering that come the mix and you have to put all these tracks together, who gets first shot at it?

JA: I’m a great believer in not having too many cooks. James Farber did the first mix. Then Sasha and I listen, make a few suggestions, bringing something out, maybe change a few positions in the soundstage, maybe adjust reverb a bit—but it’s basically James who’s creating that mix.

Matson and Sears mixer James Farber.

Matson and Sears mixer James Farber.

PS: And Joe, your method?

JH: Well, for Little Woodstar at the EastWest session we—Steve Genewick was the session mixer—had the drums isolated but that was it, since it’s a much larger room. As far as the voices, they were recorded in New York by Chris Allen, who did the final mixdown.

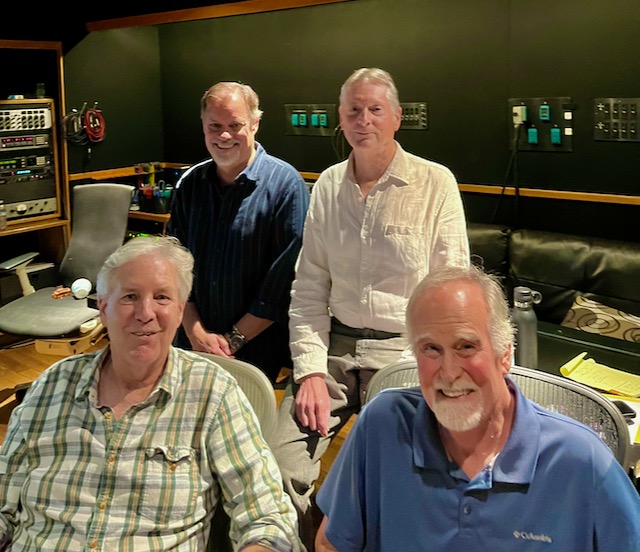

Front L to R: Sasha Matson and producer Joe Harley; back L to R: Steven Genewick, East/West mixer, and Peter Kent, concertmaster Little Woodstar at East/West Studios.

Front L to R: Sasha Matson and producer Joe Harley; back L to R: Steven Genewick, East/West mixer, and Peter Kent, concertmaster Little Woodstar at East/West Studios.

PS: I was really impressed by how convincingly the vocal quintet was folded into the EastWest orchestra mix. Impossible to tell there were two different venues.

JA: The voices were very close-miked so there’s almost no room tone from Sear on their basic tracks, so it wouldn’t necessarily clash with what Joe and Steve did in LA.

Sears mixer Chris Allen and producer John Atkinson.

Sears mixer Chris Allen and producer John Atkinson.

PS: So I have to ask—is this one all analog? Before you answer, let me say that I’m not a digiphobe, I enjoy my CDs, my SACDs, my Qobuz streaming as much as I enjoy my LPs.

SM: The native format of this album is 24/96. Why? Because as the engineers themselves have explained to me, the higher resolution PCM format and DSD are fine if you’ve got a little coffee guitar trio going straight to stereo, but when you get this kind of multitracking, this many microphones—first of all, you need a ton of memory, a huge system to process all that. Otherwise, it can be very unstable, right, Joe?

JH: One hundred percent, especially with DSD, which is really really tricky in a multitrack situation, so most people don’t want to use it. The gear, the software doesn’t really exist to allow that yet. But high-resolution, 24/96 and 24/192 works great, no problems.

PS: John Siau, who makes some of my favorite electronics, the Benchmark gear, told me he thinks 24/96 is the sweet spot.

At this point there were nods of assent from all three gentlemen.

SM: 24/96 has become kind of the new go-to—if you notice, almost all high-res, hi-def Qobuz is 24/96. You can still get two-inch tape and the studios in the back all have 24-track machines, but the tape isn’t that reliable, is it, Joe?

JH: No, it isn’t. I love analog, love analog. But I’ve had too many times where in a session we had a track going and all of a sudden you would hear pa-poomp! And the reason for that is a wrinkle in the two-inch multi-track tape. After that happened the fourth or fifth time, I was like, fuck it, I don’t want to deal with this anymore.

PS: Then let me ask the three of you as professionals in different and often overlapping areas of music, sound recording, and sound reproduction, since there will be a compact disc and eventually a streaming file of this album and you have made the best possible case for doing the work in digital, what the hell does the vinyl give us? How can it be possibly better than the original digital files since it has to be at least a generation or more removed? What’s the point?

SM: Let me answer in ten seconds by way of what my Stereophile colleague Tom Fine calls the “analog black box”—inherent distortions that can be and often are pleasing to our ears, notably in the second harmonic, for example, which means there can be a more pleasing result in transferring excellent digital to analog processes. That’s what I think.

JH: Exactly. I used to say this some years ago: there are artifacts, there’s some phase things that happen, some crosstalk, some, as you say, second harmonic distortions that are really pleasing, that we like—it presents itself as bigger [he gestures by opening his arms wide]. You know, I’ve got a great digital rig, but I can play the exact same thing on my analog rig and I’ll choose for pleasure the vinyl almost every time (unless there’s something wrong with the vinyl). Do I know that partly what I’m reacting to are artifacts that are super pleasing? Yeah, I know that, and I’ll still pick the vinyl every time. For whatever reasons, the digital comes across as smaller, a little narrower. But is it more accurate? Might be, probably is. But personally I’ll choose the vinyl every time.

JA: I’ve been recording since the early nineties, first 20, then 24-bit, mostly at 88.2 kilohertz because the downsampling to CD can be pretty much transparent. I sent Tom Fine an LP of one of my digital piano recordings, mastered and cut by Stan Ricker from the digital masters. Tom had the CD, which he thought a very good recording of a piano but “cold.” When he heard the LP, he told me, “You know, now this is what I like. This is warm, and it’s an enveloping sound.” I said, “But the CD is actually true to the recording. The vinyl is not.” Yes, but it’s as Joe just said, the vinyl is more welcoming.

PS: I’ve often thought that with LPs there’s more random phase “information” than with digital, and that happens to produce a very euphonic effect.

JA: That may be, but in addition there’s the fact that when you play an LP there’s a ritual to it. There’s placing it on the platter, opening the big beautiful jacket, reading the sleeve notes—all this sets your mind up to be more receptive to the music.

SM: My previous album Molto Molto was LP mastered from analog tape. This new album was mastered directly from the digital files. I must emphasize, Paul, that John has mastered all the digital for me on now four albums. Almost everyone who’s heard the CDs of those albums tells me, “Wow, these sound pretty good.” And I say, “Yeah it does, because John knows what he’s doing.”

PS: Does anyone have some final thoughts?

SM: It’s all about the collaborators. To work quickly at a high-quality level you need great engineers. The album benefits from the talents of Steve Genewick in Los Angeles and Chris Allen and James Farber in New York, both of whom have extensive experience with jazz recordings. Another key part of my SWAT team are my producers John and Joe. Joe produced my first album in 1992 for the AudioQuest Music label, and he was onboard for the recent Los Angeles session for this one. John has now worked with me on four albums. Both of these guys are expert at calling balls and strikes in the heat of battle, and are hands-on with the subsequent editing, mixing, and mastering processes. For me, the payoff of being a composer is getting with great musicians, in great studios, and hearing for the first time what you wrote.

[1] One of my favorite literary anecdotes has T. S. Eliot addressing a group of readers, one of whom asks why the aging Prufrock wears the bottoms of his trousers rolled up. Eliot answers that when he took his lunch in the park near the bank where he worked, he noticed most of the old men wore their trousers that way. The young woman who asked the question then offers that she thought the image was intended to suggest Prufrock is shrinking with age. Perfectly happy with that, Eliot replies. Meaning always extends beyond an artist’s intentions—indeed, I’d argue that’s one of the defining characteristics of good vis-à-vis bad art.

[2] This quotation or similar ones have been attributed to Faulkner, Picasso, and Eliot. In The Sacred Wood (1920), Eliot writes, "Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different." Handel was one of the great thieves in the history of music, so was Brahms. But in the baroque era, theft like Handel’s was typically considered flattery, especially when the thief was a composer of his genius; as for Brahms, another of music’s great purloiners, it was a way of honoring the “victim,” and a lot of the time he expected knowledgeable colleagues and listeners to recognize the theft. (When told that the famous theme from the last movement of his first symphony sounded like the joy theme from Beethoven’s ninth, Brahms replied, acidly, “any ass can see that!”)

[3] It doesn’t help that the singer pronounces “little” closer to “lettle,” like the “e” in requiem. And when vocal parts are written as melisma, as many of them here seem to me to be, I do not believe I am being churlish to suggest singers often have to mediate between smoothness and enunciation. I must also add that the singing here is always beautiful, at times radiantly so.

.png)