Heifetz Sings in Glorious Mono

Impex bring to light a little-known, early high fidelity gem

One of my favorite classical records of the last few years is Impex Records’ stunning reissue of violinist Jascha Heifetz and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky’s Beethoven Op. 1 trio on RCA (LSC-2770). This often overlook record originally released on the much-maligned RCA Dynagroove label has been brought back to life, sounding worlds away from the compressed original.

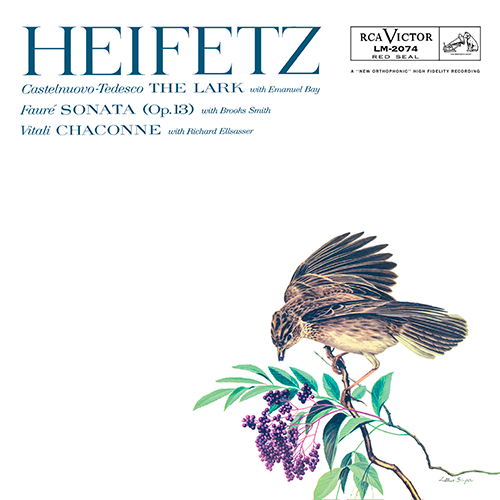

I had secretly hoped the label would be dipping its toes back into the RCA classical waters, but I think myself and most enthusiasts were surprised when Impex announced at the start of this year a mono release, returning to the catalog Jascha Heifetz's 1957 solo recording LM-2070, otherwise known as “The Lark”.

This record was actually quietly reissued by South Korean audiophile label Analogphonic back in 2018. Their version was remastered by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney Meyer at Emil Berliner studios. While I can’t confirm, I would assume that version was produced from a tape copy, or a high resolution scan, as, at this point the original RCA master tapes are unlikely to ever leave New York.

Impex had the stateside benefit with their reissue, and enlisted the help of Andreas Meyer at Swan Studios in New York go back to the original ¼ inch 30ips mono “work parts.” These original masters were meticulously restored, including a replacing of all the original tape splices. After that, using a pair of Studer A80 decks, a 1:1 tape copy to ½ inch was made , which became a “cutting master,” sent to Los Angeles and cut by Bernie Grundman on his his Westrex head fitted Scully lathe under the supervision of Impex’s Bob Donnelly, and then plated and pressed at RTI on 180g vinyl.

The presentation is also top notch, with a "tip-on" thick cardstock jacket with glossy front, and an in-depth liner insert going into great detail about the original recording process, the remastering task of Impex, and of course the artist himself. Why go to all this trouble for a monophonic violin recital record? Well, that’s because it’s not just any violinist in the grooves…

Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987) needs very little introduction. The Russian-American was arguably the greatest violin virtuoso of the 20th century, he was also a prolific recording artist who fortunately caught much of the “golden age” era of classical stereo recording, with a number of wonderful recordings on RCA "Living Stereo" in the late 50s and early 60s. Coming up in the music performance world, Heifetz was the name on every violinists lips, and bellowing from the crude iPod speakers of every player’s dorm room at the Manhattan School of Music. He had that special combination of an astoundingly clean technique coupled with a large, warm tone, and astute expression. There have been many incredible masters of the instrument before and after Heifetz, but it’s a bit like being a jazz saxophonist when there’s only one Charlie Parker…

In 1917, the 16-year-old Heifetz made his much-anticipated Carnegie Hall recital debut to an audience of New York’s musical who’s-who. Reportedly, just before the start of the concert, violinist Mischa Elman (an accomplished recording artist in his own right) turned to his neighbor and remarked “Phew, it’s hot in here,” to which his neighbor, pianist Leopold Godowsky, replied “Not for pianists…” It was in this 1917 Carnegie Hall program that the young Heifetz opened with the Chaconne in G minor accompanied by organ, which just happens to be the opening work of this 1957 album.

The Chaconne is a Baroque-era piece attributed to Italian composer Tomaso Antonio Vitali (1663-1745), but its authenticity is murky at best, and many musicologists speculate it may be a 19th century forgery, although last I checked that debate is still raging with people now arguing that it is in fact original. Regardless, it emerged as a popular violin recital piece in the late 19th century with a violin and piano edition (rather than the “original” continuo part) arranged by violinist Ferdinand David.

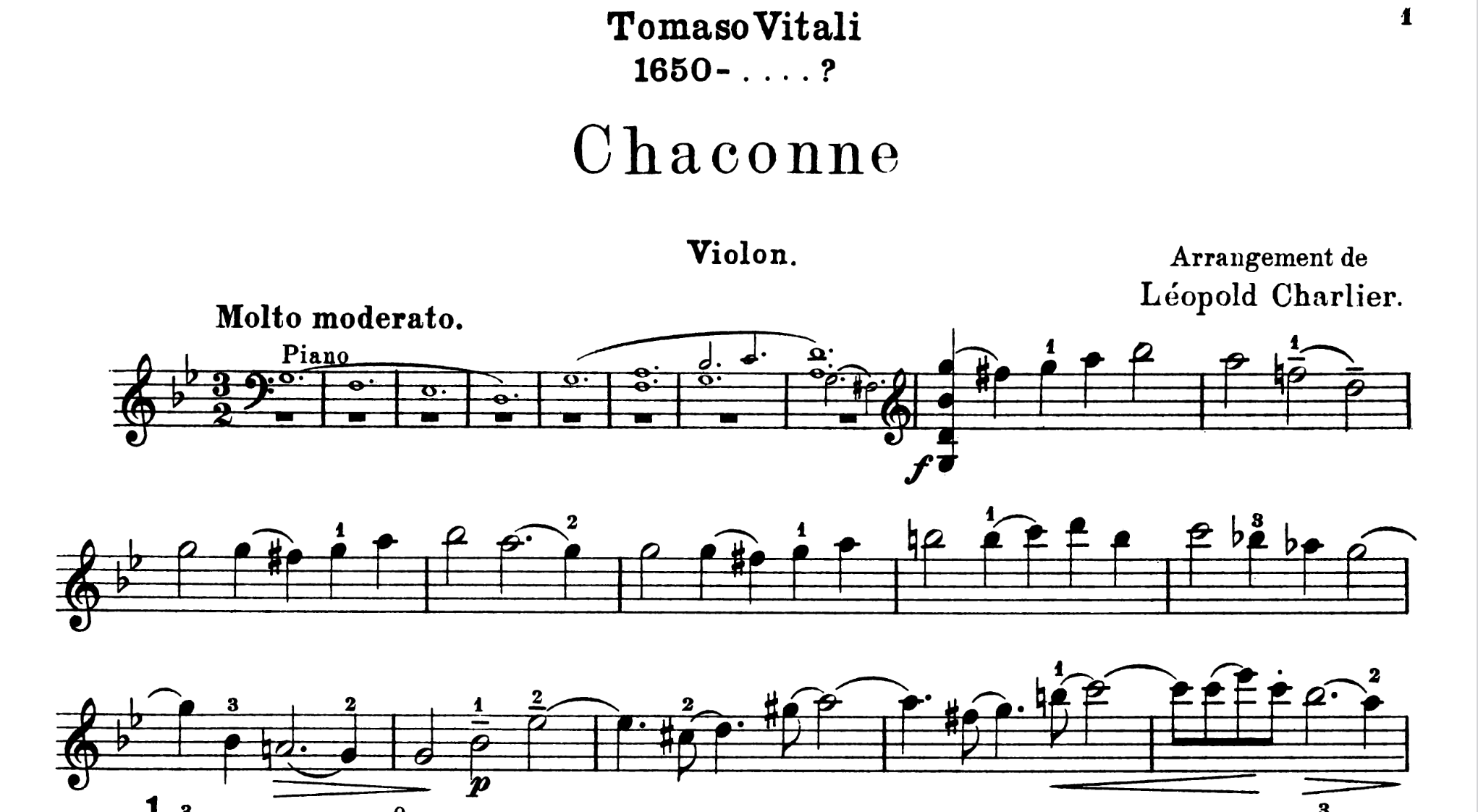

Now, here’s where things get a bit confusing. The record jacket of this LP, a facsimile of the original, lists the arrangement Heifetz performs here with violin and organ, as the one by Italian composer Ottorino Respighi. However as far as I can gather, the version by Respighi is not for violin and organ, but rather for violin, organ, and string ensemble. The interior liner notes by Impex state that this version was arranged by Heifetz for violin and organ, but I couldn’t find any sourcing for that claim. Elsewhere I was able to find allusions to Heifetz usually performing an arrangement of the piece by Leopold Charlier for violin and piano, edited by his teacher Leopold Auer. Looking at the public domain sheet music for both arrangements, it appears Heifetz is actually playing the Charlier arrangement, not the Respighi version, simply replacing the piano with organ, which features slightly different solo and accompaniment parts.

For instance, the Respighi arrangement begins with the violin solo voice straight away, while the Charlier begins with eight bars of keyboard introduction, and the Charlier also has a very specific written cadenza which is the cadenza played on this record. Heifetz apparently played this Charlier version with this instrumentation on both his debut recital, as well as on his recording here. Why the record jacket says Respighi is a mystery, other than the guess that someone at RCA saw “Vitali Chaconne” and “organ” and assumed it was the Respighi version. It’s also a mystery to me why so many reissues of this recording reissue the same liner notes. But this is all ancillary to the thrust of this review, so now back to our regularly scheduled programming. The Charlier-arranged Chaconne

The Charlier-arranged Chaconne

Heifetz’ rendition of the Chaconne is definitive for what it is, and that is a highly romanticized reimagining of a (possibly) Italian-baroque work. There is no “period performance” style here, instead the violinist leans into his lush and vibrato-laden sound to produce a showstopping and emotive performance, led on by the fine work of organist Richard Ellsasser. At times, the organ stops chosen blend seamlessly with the string tone of the performer's violin, and it occasionally sounds as one instrument in the more busy passages. This is the oldest recording on this album, done in 1950 at Bridges Hall in Pomona, CA. However in some ways I think it sounds the best out of the three works, with the organ providing an immediacy and fullness that the piano sound on the other cuts can’t quite reach (but I’ll get to that later). This recording might not have the resonance of RCA’s later stereo recordings, but the tone quality is sweet and singing. Heifetz preferred a close-mic’d violin sound, with the accompaniment off a bit in the distance, and this perspective comes through clear as day in this remastering. The organ, while nowhere near the sound of the great Mercury Living Presence organ records that would come a few years later, is weighty and deep, giving my Rel T/7x a nice workout.

Bridges Hall at Pomona College

Bridges Hall at Pomona College

The Chaconne is followed with a short tone poem by Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) bearing the subtitle of this LP, The Lark. Castelnuovo-Tedesco had a long association with Jascha Heifetz, as Castenuovo-Tedesco wrote many works for the violinist, and Heifetz conversely assisted the Jewish composer from fleeing fascist Italy to the United States in 1939. "The Lark" was written just before this tumultuous period, in 1931, and was commissioned by Heifetz himself. It is inspired by a passage of Shakespeare’s play Cymbeline, and takes the form of a fantasy Rondo. While the music of Castenuovo-Tedesco has fallen out of the repertoire somewhat since the 1950s, he had a long career composing both classical art music, as well as writing scores for over 200 Hollywood films and teaching some of the most brilliant film composers we know today such as Jerry Goldsmith and John Williams.

"The Lark" may be a tone poem in the post-impressionist tradition, but it features enough flair to be considered a showpiece for the instrument, and Heifetz’s navigation of the difficult scales and runs scattered throughout stands as a testament to his dexterity and agility. Sound quality and image for the violin is also excellent here in this 1953 recording done at Radio Recorders in Hollywood, CA. The piano accompaniment by Emmanuel Bay is sensitive, and the pair work excellently as an ensemble, however here the piano sound does come across a bit dated, with a muffled and hollow quality. There is none of the transient attack excitement that one expects from the instrument, and the contrast between that sound and the brilliance of Heifetz’ “front and center” ring does make you notice the year in which it was recorded.

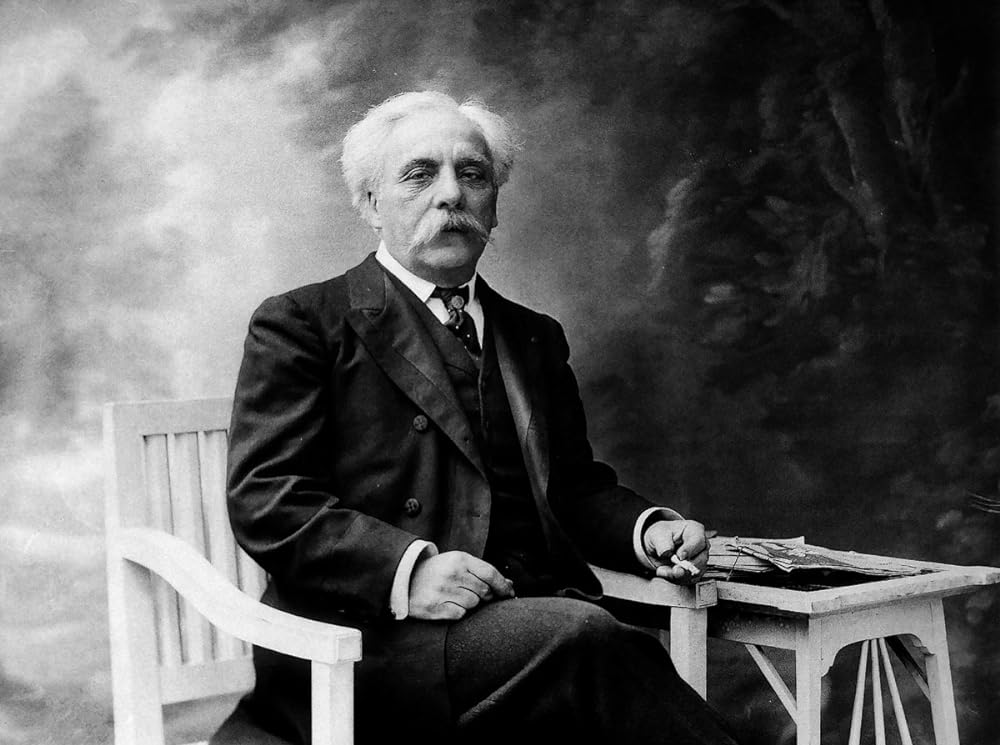

Side two contains the most “standard” piece of repertoire on this disc, Gabriel Fauré's (1845-1924) Violin Sonata No. 1 in A, Op. 13. Published in 1877, it is considered one of the hallmark compositions of the French composer’s youth. The piece is thoroughly romantic, with a four-movement structure and reliance on sonata form. However there are hints in this work of the composer’s often-noted link to the modernist and impressionist schools of the early 20th century, such as unique rhythmic and tonal modulations. If you find yourself typically drawn to the music of Maurice Ravel as I often am, you will find much to like in the music of Fauré, and you can hear many of the harmonic blueprints of that music here in this Sonata. Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré

The performance of Heifetz and his accompanist Brooks Smith on this 1955 recording date is profound, insightful, and above all exhilarating. Navigating the twists and turns of this piece is no easy feat, and to do so with technical clarity and bravado to boot lets the listener know they are hearing an exemplary performance. This was particularly noticeable to me in the 3rd movement scherzo where the soloist and keyboardist are able to navigate between sorrowful and inward looking melodic lines, then burst from upbeats to exciting and exacting quick ascending lines, including brilliantly executed pizzicato moments.

The fourth movement finale is a singing triumph, and both players put forth a full dynamic range, which this remastering brings out to the best of its ability. When Heifetz rips into his high register in fleeting moments of power and terror, I was amazed at the texture and energy rendered by this early hifi recording. Now here, like in the "The Lark", the piano does take a backseat in the soundstage, and still retains that hollow muffled quality, but that sound seems to be intrinsic to the recording and/or perhaps this particular recording studio as both works were recorded at Radio Recorders. Nevertheless, Heifetz with his gigantic sound, is right in front of you in this presentation, and it's thrilling.

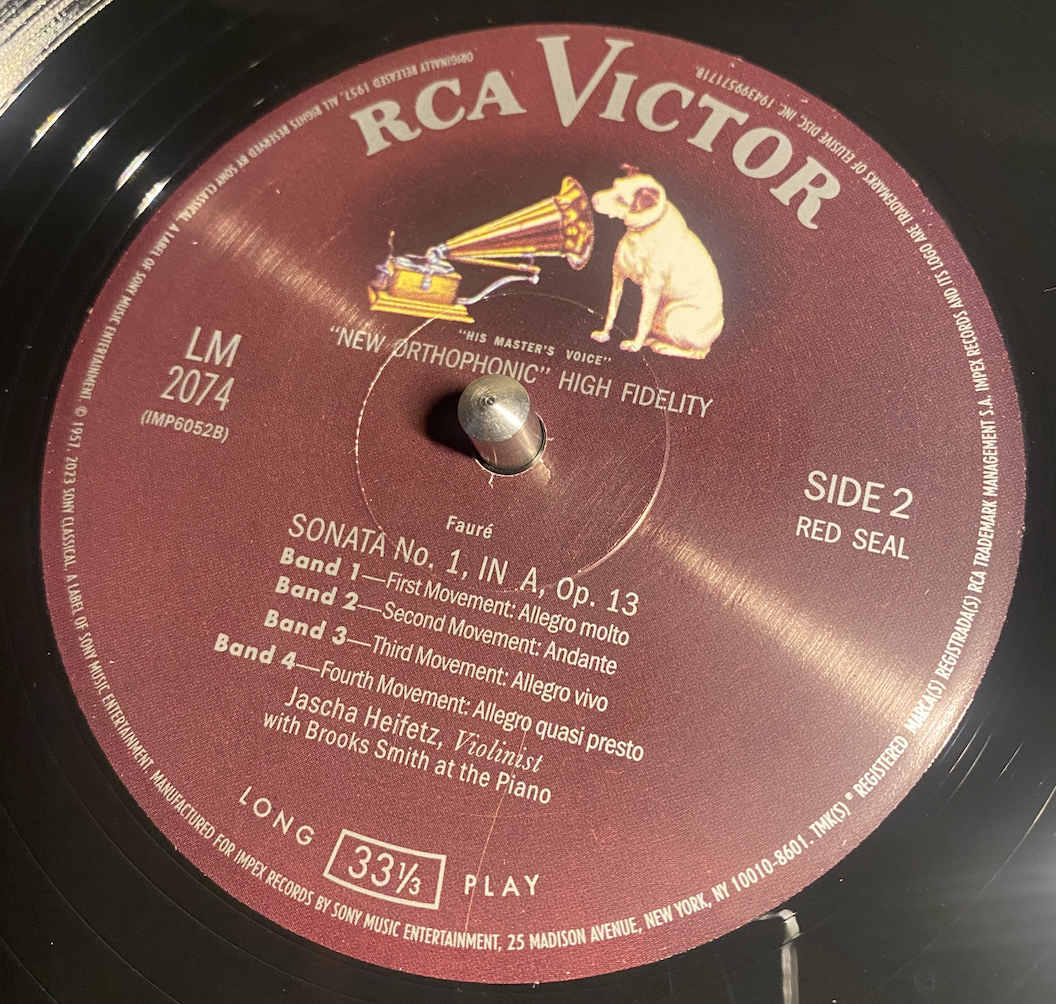

Don’t let the fact that this album isn’t a Harry Pearson-rated sonic orchestral showstopper steer you away. This is a beautiful album of one of the masters of the violin, performing intimate recital repertoire, recreated with love and care from one of the best AAA reissue labels in the game today. It is clear from everything including the packaging, mastering, documentation, and even the beautiful recreation of the original RCA Nipper maroon mono label, that for Impex this was a labor of love, and I hope not the last boutique classical effort from the label. With Analogue Productions putting their Living Stereo series on indefinite hiatus, the gems of the American classical music labels of the 50s and 60s are ripe for reissue, and we can only hope that this wonderful reissue is a hint at more to come.

Here's Mark Ward's video review:

.png)