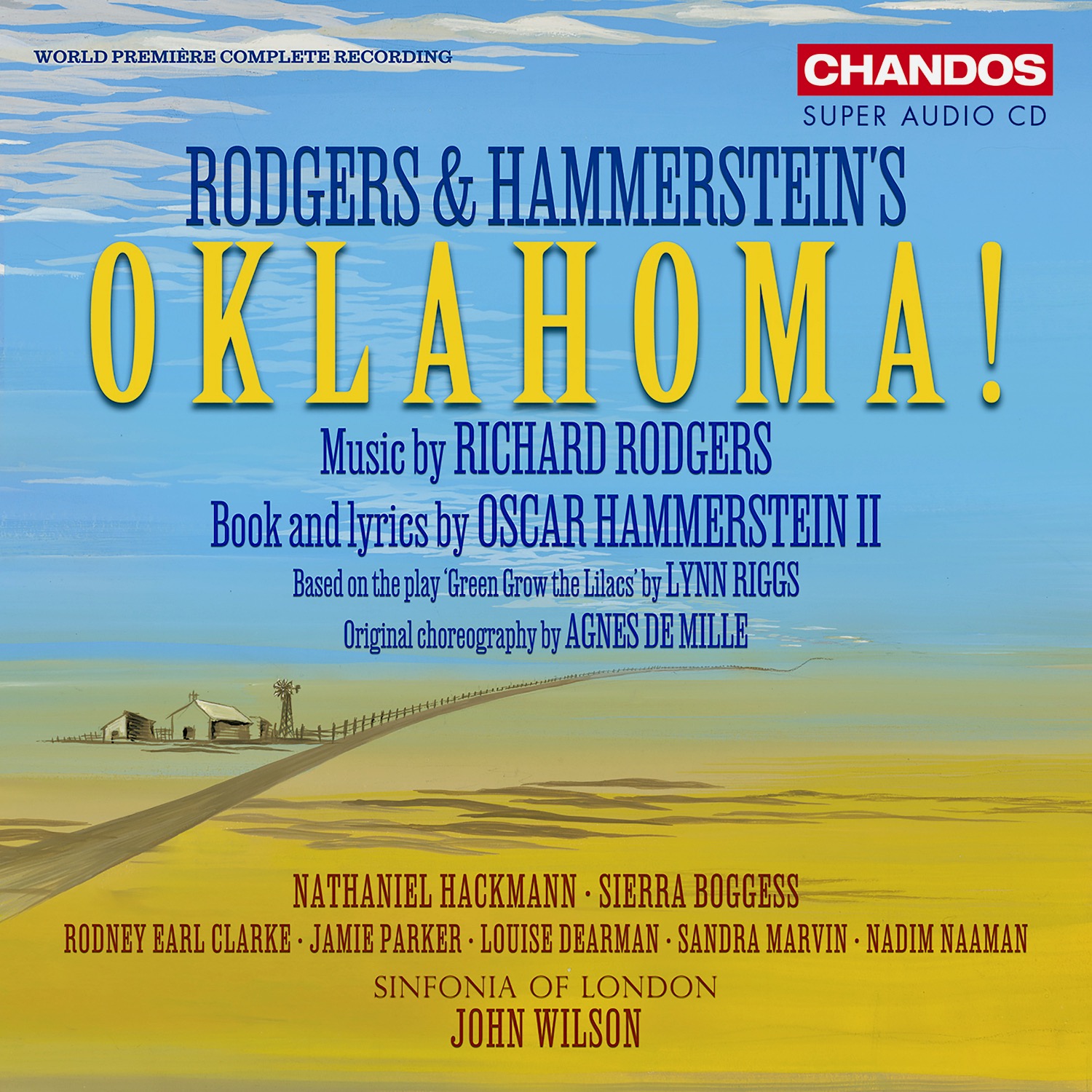

John Wilson's Magnificent New "Oklahoma"!

World Premier Recording of the Entire Score

The musical Oklahoma! was not of course written or composed by the conductor John Wilson. It was the first of a series of spectacularly successful collaborations by the composer Richard Rodgers and the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, who also wrote the book (musical theatre parlance for the whole play, meaning the entire script including dialogue and sometimes the lyrics). It opened in 1943, nearly thirty years before Wilson was born and ran for five years and an unprecedented 2,212 performances (typically to sold-out houses); a second company toured the United States for ten unbroken years; and beginning in 1947 it ran for three years in London. In 1944 it was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize; in 1955 the movie version won two Academy Awards (best score and best sound recording) and in 2007 was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Meanwhile, Oklahoma! became a classic that entered the standard theatrical repertoire and has been revived countless times here and abroad, not to mention—despite the sophistication of the score and Agnes de Mille’s innovative, demanding choreography—a staple of semi-professional, community, college, and high-school productions. It has been revived five times on Broadway (most of which won awards), most recently in 2019 at the Theatre in the Square in New York City, a fairly radical rethinking that sought to expose the underside of its “bright golden haze on the meadow” surface.

lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II and composer Richard Rodgers, c. 1943

lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II and composer Richard Rodgers, c. 1943

The Musical That Changed Musicals

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the success of Oklahoma! is that it happened at all. It was adapted from a play by Lynn Riggs called Green Grow the Lilacs, which opened on Broadway in 1931, ran a modest 64 performances, and was thereafter hardly ever revived, its only claim to anything like fame being as the source for the musical. Riggs was born in 1899 near Claremore, Oklahoma, in what was then known as Indian Territory (a large section of Southwestern land without statehood set aside by the Federal Government for the relocation of Native Americans); his mother, one-eighth Cherokee, died before he was two; his father, a cowboy who became a bank president, remarried. With pretty narrowly traditional ideas of what and how men are supposed to be and behave, neither father nor new stepmother had much sympathy for the slight sensitive boy who dreamed of writing poetry and plays and turned out to be gay. Lynn was eventually sent to live with his aunt Mary Brice Riggs, who ran a boarding house in Claremore (she became Aunt Eller in the play).

It's hard to imagine a less promising source for commercial success as a musical on the Broadway stage of the early forties. Several characters are based on people Riggs knew growing up, and despite the fact that the three main characters, two men and a woman, constituted a triangular relationship, his intent was neither romance as such nor comedy. Like the characters, the setting isn’t just rural, it’s practically fringe-area frontier: a farm and neighboring ranch near his hometown in the Oklahoma of 1900, seven years before it became a state. By contrast, most musicals were romantic comedies, urban and contemporary, with stylish, sophisticated high-society types, their (usually irreverent) servants, sometimes an assortment of roguish gangsters, hoods, and molls, and occasionally chorus girls and other theatrical people. The characters were thin, the plots thinner, the songs, dances, and other music having at best a casual, even indifferent connection to story and character—or none at all.

Rodgers and Hammerstein were determined to write a musical in which all the elements—score, songs, lyrics, dances, drama, plot, and character—were fully integrated toward dramatizing a story about people who are realistic in the specific sense that audiences could identify with or relate to them, and in which the relationship among action, staging, and dialogue to music is organic, lyrics seamlessly emerging out of dialogue, sometimes segueing back into dialogue, then to song again, often interlaced with dance. In other words, the songs and dances weren’t “numbers” that often as not stopped the show, instead were integral to the structure and advanced the story and developed or deepened the characters. As David Benedict puts it in his excellent essay for this new Chandos recording,

"At root, what Oklahoma! did was kiss goodbye to vaudeville and create the “musical play”. Out went interchangeable numbers often chosen on the whim of the leading actors in what were little more than star vehicles that moved from one painfully obvious song to another. In their place, Hammerstein . . . created the first drama on the musicals stage to be built around a coherent plot that was determined, crucially, by three-dimensional characters."

Hammerstein made no attempt to modernize or change Lilacs’s story in order to cater to the prevailing tastes for what was popular on Broadway. What Hammerstein did do was cut but, as I shall show later on, by no means entirely eliminate the darker, grimmer parts of the play (notably the psychological aspects), in order to make it into a romantic comedy. Otherwise, he stayed close to the basic storyline, structure, order of scenes, and characters and helped himself to quite a lot of the dialogue because he felt it couldn’t be improved upon. For good reason, the play itself is an example of the regionalism, or “local color,” movement so popular in American literature and culture in the second half of the nineteenth and well into the twentieth centuries: works that depicted and often celebrated specific regions, paying particular attention to accurate depictions of people, places, landscape, customs, dialects, and history.

Inasmuch as Riggs had incorporated at least nine folk or popular songs into Lilacs (all sung by Tex Ritter in the original run), the play already seemed primed for full musical treatment. Those songs were jettisoned in favor of wholly new ones, many more were added, and Rodgers wrote a rousing overture, one of the best in the history of musicals. But once it was finished, the curtain rose not on the usual chorus of high-kicking scantily clad girls, rather on a mostly empty stage with an elderly woman churning butter, while the music turned soft and bucolic, with plaintive horn and chirping flute. Soon enough, offstage in the distance we hear a baritone singing “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” one of the most expansively lyrical melodies ever to grace the American musical stage, sung by a strapping young cowboy thinking about the woman he’s come to ask to the box social that evening.

Odd as it may seem, this was actually a daring, even risky opening for a Broadway musical, and it worried everybody from the librettist and the composer to the performers to the investors. Mike Todd, who would later produce the movie version, famously left the first tryout in New Haven at the intermission with a wisecrack on his lips, “No legs, no jokes, no chance!” (an unexpurgated version was reported as, “No tits, no jokes, no tickets!”). In the end, the joke was on Todd and all the others, including some Broadway gossip columnists, who took delight in repeating the quip. (Todd later apologized for it and for leaving early.) But Agnes de Mille, who was also there, remembers a very different reaction to that supposedly dull, uncommercial opening: “a sigh from the entire house I don’t think I’ve ever heard in a theatre. It was just ‘Ahh.’ It was perfectly lovely and deeply felt.” It was also the first indication that audiences were ready for the new kind of character-driven musical Rodgers and Hammerstein were pioneering. After an opening like that, the critic Brooks Atkinson wrote in the New York Times, “the banalities of the old musical stage became intolerable."

Rodgers and Hammerstein retitled their adaptation Away We Go! and advanced the year to 1906, when the territory was on the cusp of statehood. After a few revisions during previews and tryouts, they changed the title again, this time to Oklahoma!. “Oklahoma” was also the title of one of the songs. Originally written as lyrical piece sung by Laurey and Curly (with some dancing), it was rearranged by the show’s orchestrator Richard Russell Bennett as a sensational eight-part chorus for the whole ensemble and orchestra so as to end on a ringing celebration of imminent statehood, communal harmony, and fervent patriotism for a country and world still at war (remember, in 1943 Allied victory was far from certain).[1] Little wonder that when the show became a hit, then a perennial, it came to epitomize the quintessential American musical, embodying wholesome, homespun, homegrown values and virtues: “synonymous with sunny American nationalism for more than three-quarters of a century,” in the words of the critic Frank Rich, the corn “always as high as an elephant’s eye and the skies are not cloudy all day.”

A celebration of communal harmony in a time of war

A celebration of communal harmony in a time of war

Well, okay—strip this of its condescension and so far as thumbnail description goes, it’s accurate enough. But even a cursory experience of any production that’s at least decently played, sung, and acted will demonstrate its incompleteness and superficiality. On the surface the book Hammerstein fashioned from Green Grow the Lilacs appears to be, and can certainly be enjoyed as, little more than a folksy romantic comedy set in the boondocks of the Southwest centering on three couples, all involving triangular rivalries. However, Oklahoma! is also thematically rich, suggestive, layered, even large-scaled, embodying, referencing, or otherwise touching upon conflicts of class, gender, lifestyle, economics, progress, even manifest destiny. “The Farmer and the Cowhand” is a comic treatment of one of the central conflicts in the history of the American West and a theme of countless Western novels, movies, and TV shows: homesteaders versus cattlemen, settlers versus cowboys, who gets to control the range and how it’s divided up. A square dance begins with good-natured badinage, yet despite a refrain that urges territory folks should stick together and all be pals—"cowboys dance with the famers’ daughters,/farmers dance with the ranchers’ gals”—the ribbing soon approaches insult that threatens to break into a brawl that is in turn averted only when Aunt Eller fires a gun to stop it.

In “Kansas City,” which contains some of Hammerstein’s’ wittiest lyrics, we find another division, rural versus urban, country versus city, that goes deep down and far back in American society, a country fellow, here a cowboy, fresh from a trip to the titular town regaling his friends and neighbors in wide-eyed wonder with all the modern sights, sounds, inventions, and conveniences he saw: twenty gas buggies going by themselves, a skyscraper seven stories high, radiators whenever you want heat, telephones with voices on the other side, and privies you can walk to in the rain without ever wetting your feet. “They’ve gone about as fur as they c’n go,” he concludes, whereupon he launches into the two-step, a new dance he’s learned which he teaches the group as they all join in.

Agnes de Mille's innovative choreography

Agnes de Mille's innovative choreography

As with the themes, so with the characters. But aren’t they all just types, stereotypes, even cliches? Of course, they are—so what? This is true of the characters in most of the operas and plays ever written, high or low, serious or comic, going back past Molière and Shakespeare to the likes of Sophocles and Aristophanes. What matters is how they are realized, individuated, and brought to life in dialogue, music, and song. To get an idea of how character-driven this musical is, not to mention how tightly structured, integrated, and bound are all its constituent elements, consider that almost every scene, situation, song, dance, ensemble, and plot turn is determined by, develops out of, or ramifies from an unresolved issue in the relationship between the main couple Laurey and Curly, an issue introduced in the very first scene. Laurey, intelligent, a little shy but headstrong, independent, and prickly at times, resents what she perceives as Curly’s blithe assumption that she will be his escort to the Box Social. Both are too proud to admit how much they care for each other (if “People Will Say We’re in Love” isn’t the most beautiful song ever written about a couple who are in love while insisting they’re not, then its only superior is “If I Loved You” from Carousel, by the same team). In order to make the point, Laurey allows her brooding, baleful farmhand Jud Fry, who has a mysterious, possibly criminal past, to believe she might welcome his invitation to the social.

This leads directly to the confrontation between Curly and Jud in the smokehouse, where angry words are exchanged, shots are fired, and Jud warns Curly to stay away from the farm and Laurey. Once alone, Jud sings his soliloquy “Lonely Room,” which expresses his anguish and loneliness owing to the way he’s been treated and ostracized by the community; by the time the song ends, anguish gives way to anger as he resolves that he’s not going to dream about Laurey any longer, “ain’t gonna leave her alone!/Goin’ outside,/Git myself a bride,/Git me a woman to call my own.”

Laurey meanwhile, distraught and confused, has fallen asleep under the spell of an elixir that’s supposed to help her make up her mind, which sets up the “Dream Ballet,” a 15-to-17-minute dance sequence that ends the first act, charting the course of her feelings for Curly, her guilt over playing him and Jud against each other, and her fears that Jud may try to harm Curly and herself. It begins happily as she imagines Curly courting her, proposing marriage, until Curly, suddenly, horrifyingly, turns into Jud, whereupon the dream becomes grotesque. The women on the pornographic French postcards and pink Police Gazette covers hanging in Jud’s room come to life, swaying with provocative moves and gestures in a sleazy dance that taunts and humiliates Laurey. Now nightmare, the dream ends in murder and would end in abduction and rape except that the real Jud awakens Laurey before the nightmare Jud finishes what he’s begun.

The French postcards come to life in the "Dream Ballet"

The French postcards come to life in the "Dream Ballet"

With neither songs nor dialogue, only music and dance, the ballet became the most ground-breakingly original and emotionally expressive sequence in Oklahoma!, with strong elements of surrealism (a movement that predated Oklahoma! by only a decade and a half and was still powerfully influential across all the arts). According to the Broadway historian and critic Laurence Maslon, Hammerstein envisioned the ballet as a circus, “bizarre, imaginative and amusing, never heavy,” nothing like the violent, sexually charged nightmare it became. It was the choreographer Agnes de Mille, never shy about voicing her opinion, who steered it in that direction. De Mille, who had undergone a lot of psychoanalysis herself, told Hammerstein,

"This is the kind of dream that young girls who are worried have. She’s frantic because she doesn’t know which boy to go to the box social with. And so, if she had a dream, it would be a dream of terror, a childish dream, a haunted dream. Also, you haven’t any sex in the first act. He said, haven’t I? I said, goodness, no. All nice girls are fascinated by [the darker side of sexuality]. Mr. Hammerstein, if you don’t know that, you don’t know about your own daughters."[2]

In drawing attention to the weightier themes and the tormented agon of the Curly/Laurey/Jud triangle, I by no means wish to suggest that Oklahoma! is in the least pretentious, heavy-handed, inflated, insistent, preachy, or obvious about any of this. Like Cosi Fan Tutti, like The Marriage of Figaro, like The Barber of Seville, Falstaff, Ruddigore, and Candide, the larger, deeper, more resonant themes are there if you notice them or want to think about them afterward, but however far the creators pushed and stretched the boundaries of musical comedy, they never violated the overall tone, which is light, witty, comic, satiric, and romantic. Indeed, for a show that is sometimes dismissed as corny and square, its treatment of most of the characters’ love lives, de Mille’s remark to Hammerstein notwithstanding, is surprisingly, delightfully casual, carefree, insouciant, irreverent, modern, even hip. Laurey’s “Many a New Day,” where she declares she will never allow her self-esteem to be defined by the men in her life, is practically proto-feminist in its fierce independence.

Set against Laurey, constantly fretting, is her best friend Ado Annie, whose first song, the bawdy “I Can’t Say No,” introduces us to a sexually liberated woman so secure in her appetites she’s unafraid to indulge them, even in a society that doesn’t know what to make of her. Annie’s happy to be wooed by—and share her pleasures with—the cowboy Will Parker and the peddler Ali Hakim (not to mention, apparently, any of several other eligible fellows who pay her attention): “Fer a while I act refined and cool/A settin’ on the velveteen setee./Then I think of that ol' golden rule/And do fer him what he would do fer me.” In a nice reversal of the usual roles, it’s the cowboy, all too ready to leave the bachelor’s life, who declares himself a one-woman man and demands Annie give up her freewheeling ways if they’re to be married. She agrees—sort of, but it’s pretty clear she would happily accept the kind of marriage a later generation would call “open”. There’s a deliciously naughty moment near the end when she and Will reappear after an absence, disheveled but flush, with big grins on their faces, perfectly obvious that well before any matrimonial vows have been exchanged, they’ve taken their sexual pleasures about as fur as they c’n go. And earlier, when Will returned from Kansas City, he talked about a “burleekew” show with a gal who “was fat and pink and pretty./As round above as she was round below.” He could swear that “she was padded from her shoulder to her heel,/But later in the second act when she began to peel,/She proved that ev’rythin’ she had was absolutely real!”

Curly is occasionally dismissed as a handsome hunk, not very bright, and something of a bully. I see nothing in the text or lyrics to support this last.[3] Granted that when he tells Jud that Jud’s alienation is at least partly self-inflicted, it comes more out of antipathy than of sympathy, but it’s also acutely perceptive and on the mark. What’s more, Curly’s smart enough to realize that if he’s to have any sort of future with Laurey, he'll have to give up his life as a cowboy and learn the ways of the farmer.

It's almost impossible to overstate the influence of Oklahoma! on the subsequent development of musicals. Historians of American musicals often divide musicals pre- and post-Oklahoma! To be sure, it was never the first show to seek a tighter, more organic unification of all the elements of a musical toward the end of telling a coherent story with believable characters. The most conspicuous of the forerunners is Showboat of 1927, adapted from the Edna Ferber novel by Hammerstein with music by Jerome Kern, which dealt with racial prejudice, miscegenation, and treatment of blacks in America and aimed for a similarly more coherent, through-conceived form and style. But neither it nor the few others went as far as Hammerstein and Rodgers did. Or perhaps it was bad luck in the timing—with the lees of the Roaring Twenties, the stock-market crash, the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, the rise of fascism in Europe, the Nazi war machine, Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entry into the second world war, maybe audiences just couldn’t work up much enthusiasm for musicals that weren’t frivolous. Whatever the reason, those others didn’t change the game, which Oklahoma! indisputably did. Eighty years later the change remains unchanged. Nearly all the great musicals that followed by Rodgers and Hammerstein themselves, Lerner and Lowe, Bernstein and his collaborators, Sondheim, Bob Fosse, Andrew Lloyd Webber, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, to cite only the most obvious names, are inconceivable without the model of Oklahoma! behind them. Little wonder that every generation since feels the need to reinterpret it anew and make it their own.

John Wilson and Oklahoma!

When John Wilson was fourteen in his native England he was invited by his music teacher to be a last-minute substitute to play the drums in local theatre production of Oklahoma!. “I didn’t even know what Oklahoma! was, but I was chuffed that he'd asked me and the thirty quid sounded good, so I said yes. I think I learned more in that week than I have in any other single week of my life . . . there was a whole genre of music that I’d never heard of, and I kind of decided there and then that this was what I was going to do with my life.”

Once he decided to do it, Wilson did what he always does: return to the original score. Ever since he was a student at the Royal Academy of Music, Wilson has loved the classic Hollywood musicals and film scores from the thirties, forties, and fifties. In 2002, early in his career as a professional conductor, he programmed a concert of MGM film music only to discover the orchestral parts no longer existed. James Aubrey, the venial, destructive head of the studio in the late sixties, had ordered them destroyed to make for more storage room! Undaunted, Wilson, using whatever material was available (mostly piano reductions) and the soundtracks and films themselves, painstakingly reconstructed the parts by ear—a whole weekend, for example, to do the storm sequence from The Wizard of Oz. In other words, Wilson became an HIP—Historically-Informed-Performance—specialist whose area was not the pre-Baroque, Baroque, and Classical periods but the great film music and musicals of the past century.

Despite the vast number of performances and major revivals—a typical year sees as many as 300 productions—Oklahoma! is rarely presented complete. Numbers are often dropped (at least two from the 1955 movie), as is much connective, transitional, and entr'acte material, not to mention underscoring here and there. In this recording, for the first time, the entire score is presented absolutely note complete, for which Wilson drew on the considerable efforts of the late Bruce Pomahac, Director of Music for The Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization. Throughout its long history the score was reorchestrated for larger ensembles (again, the movie version), other times reduced with digital simulations to make up for not employing (or having available) more musicians. As conceived and originally premiered, the music was orchestrated by Richard Russell Bennett, a master of his craft and a gifted composer in his own right, for a pit band of 29 players (sizable for musicals of the time). Wilson not only returned to the original size and complement of players, but he secured instruments of the day to reproduce the authentic sound. “It's no different from what any number of period instrument specialists do,” he said in a Gramophone interview,

"finding the right kind of instruments, a deep bodied acoustic guitar, calfskin heads on the vintage drum kit from the 1940s, making sure that we play the correct doublings—I think the oboe player played four instruments, oboe, cor anglais, oboe d’amore, bass oboe—none of the kind of simplifications that were imposed upon the piece as the years went past. We've gone right back to those original colors of 1943."

All of Wilson’s popular theatrical and music productions—he’s been an annual presence with capacity crowds at the BBC Proms for nearly a decade and a half now—are distinguished by his expertise in finding singers who can both act and are at home with the style of the music. (The first complete Oklahoma! Wilson essayed was a semi-staged version at the Proms in 2017, a fabulous production available on YouTube, brilliantly recorded both sonically and visually.) This means avoiding traditional opera singers, who tend to bring too much weight of tone to their singing. On the other hand, mere “pop” voices aren’t right because, as the critic Edward Seckerson once put it, they need to be singers who develop their voices “vertically,” voices that, however light, also have real substance, body, and ability to project. (Since musicals are more dialogue driven than the typical opera and operetta, they have to be far better actors too.)

All of Wilson’s popular theatrical and music productions—he’s been an annual presence with capacity crowds at the BBC Proms for nearly a decade and a half now—are distinguished by his expertise in finding singers who can both act and are at home with the style of the music. (The first complete Oklahoma! Wilson essayed was a semi-staged version at the Proms in 2017, a fabulous production available on YouTube, brilliantly recorded both sonically and visually.) This means avoiding traditional opera singers, who tend to bring too much weight of tone to their singing. On the other hand, mere “pop” voices aren’t right because, as the critic Edward Seckerson once put it, they need to be singers who develop their voices “vertically,” voices that, however light, also have real substance, body, and ability to project. (Since musicals are more dialogue driven than the typical opera and operetta, they have to be far better actors too.)

Wilson’s cast could not be improved upon. Among the three principals, Nathaniel Hackmann, the Curly, is a name new to me but one who has already distinguished himself on the world’s stages. A native from Arizona, with a rich, open baritone that can get into the tenor range, he gives us a Curly of sensitivity and charm without losing any of the necessary rough-hewn cowboy masculinity, directness, and strength the part requires. Rodney Earl Clarke, an intense, powerful Jud, perfectly modulates the farmhand’s turn from tortured victim to wounded, desperate, homicidal outsider. Best of all is Sierra Boggess. When I first read that Wilson was recording a complete Oklahoma!, I hoped he would cast this tremendously gifted soprano as Laurey. Boggess, who hails from Colorado, has had a number of triumphs these last many years, including a near peerless Christine in the splendid 2012 25th anniversary revival of Phantom of the Opera in London’s Royal Alpert Hall (Andrew Lloyd-Webber pronounced her his favorite Christine, and she’s certainly the most emotionally moving I’ve ever seen in the role). With a bright, clear, crystalline voice that also includes a strong lower register, she is quite the best Laurey of my experience, not least because she can act as superbly as she sings (listen to how lovely her phrasing is in the brief reprise after Curly’s ringing climax to “People Will Say We’re in Love”). It is to Wilson’s credit that in several places he includes the dialogue that introduces and concludes the songs.

The entire supporting cast is at the same level of accomplishment, notably Jamie Parker’s Will Parker and Louise Dearman’s Ado Annie, neither of whom I’ve ever heard bettered and, frankly, no others as good. As for Sandra Marvin’s Aunt Eller and Nadim Naaman’s Ali Hakim, I can’t say I’ve not heard others as good, but, again, none better. Committed regionalist that he was, Lynn Riggs wrote the dialogue in dialect, and Hammerstein followed suit, with the proviso that the dialect was intended as guide, not as prescription. Wilson’s cast resist the temptation to lay it on too thick. As I’ve already argued, Oklahoma!, despite dark and disturbing scenes, is fundamentally a romantic comedy in a more or less folksy mode, but it is comedy completely grounded in and conditioned by character. When the characters are funny, they don’t know they’re funny, so the players shouldn’t try to act funny. The humor arises out of the situations. Nowhere in these performances is there the least hint of condescension or superiority, or any suggestion that the performers are standing apart from their characters, as performers can sometimes do when portraying country folk. All are fully invested, their conviction is absolute, and the entire play comes vividly to life even though you can’t literally see it. A word or three for the chorus: they wipe the floor with every other recording of the score, especially the final “Oklahoma” set piece, which almost takes the roof off in its celebratory fervor.

Wilson’s obsession with making this as back-to-origins an Oklahoma! as he could extended even to where and how it was recorded. “This piece was designed acoustically, it wasn’t designed for microphones,” he has said.

"You go to the theatre to interact with your fellow human beings, and the moment you have a loudspeaker in the way you lose some of the reciprocity between the stage and the audience. And so we recorded this piece as acoustically, as purely, and as simply as we could. Firstly we made a conscious decision to record it in the theatre [the Susie Sainsbury Theatre, Royal Academy of Music, London] . . . and we captured the acoustic experience. The whole thing was cast with a very great deal of care—not just the principals but the ensemble, and the orchestra was cast with as much care as the principals, because the orchestra is the beating heart of the of the piece. And I think we’ve succeeded in giving everybody the kind of experience they would have had had they been in the front row on opening night in 1943."

Chandos’s producer and engineer Jonathan Allen out does himself here. The dynamic range on this recording is very wide, deceptively so: I beg you to resist the temptation to ride the levels with a remote handset as you listen. Starting with the thrilling overture, dispatched with matchless verve and style, scurrying violin runs tossed off with breathtaking skill, set a maximum loudness level you’re happy with, then put the remote aside and surrender yourself to the performance. It isn’t just for economic reasons that the original orchestra numbered only 29 players. Bennett was not only a master orchestrator, whose orchestrations of Broadway scores from 1920 through 1965 reads like a “greatest hits” of musicals, he possessed an exceptional gift for knowing how to score for voices so that conductors did not have to do a lot of balance adjustments on the fly. Play the score as written, observe the dynamic markings as notated, and the relative levels will take care of themselves. Wilson, a master conductor himself, sees to it that we hear it that way. Never once in this recording did I feel I was hearing levels manipulated after the fact at the mixing board.

The imaging and soundstaging are thoroughly realistic such that Peter Walker’s famous “window onto the concert hall” (or other venue) is realized to a T. When the singers move toward the rear, their levels lowers because they are moving farther way, and you hear it as movement in spatial depth. In, for example, the “Out of My Dreams” scene between Laurey and her friends that precedes the “Dream Ballet,” the recording is so truthful it resolves depth between the singers to within a foot or two. At the very beginning, when Curly sings “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” he is way off in the distance—literally off-mic, which means that you hear more of the acoustics of the venue and when he moves forward he doesn’t come so close to the mic he’s in your face. That is exactly as it should be, because it perfectly establishes from the outset an aural equivalent to the wide-open prairie space that is the first scene. This is one of those recordings, still rather less abundant than they should be, where the idea of “stereo” in its root Greek sense of “solid” is actually realized.

The recording is available in several formats including a multi- and 2-channel hybrid SACD with a Redbook layer and several streaming and download options. There is also a limited edition 2-LP vinyl set (1000 copies). The booklets for both the LP and the SACD sets contain detailed notes, synopsis, and complete lyrics (though the singers articulate so perfectly you won’t need them). Sonically, the SACD and vinyl are equally superb in their different ways. The vinyl, very thick LPs with surfaces that put most “audiophile” pressings to shame, has all the warmth and richness for which we love the medium; the SACD is scarcely less desirable in this regard and scores in other areas (pitch stability and clarity). In either format, I have never heard a more realistic recording of a musical theatre performance than this one.

Wilson calls the orchestra the “beating heart” of this score, and despite its chamber size the Sinfonia of London play here with a heart as big as all outdoors and at a level of expertise, refinement, panache, and sheer brilliance that few musicals either live or recorded have ever been privileged to receive (the strings, as always with Wilson and this orchestra, scintillating or luscious, as called for). But great as the orchestra, the cast, and the recording are, in the end this is John Wilson’s triumph, not only because he handpicked them, brought them together, and inspired them to the heights they scale here, but also because the style and idiom are second-nature to him, every piece from the overture to the closing reprise of “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning,” paced, balanced, played, and sung to perfection, exquisitely phrased and beautifully shaped, with the kind of commitment and conviction that only deep and abiding love can realize. The entire enterprise has the feel of a dream come true, which of course it is: a dream Wilson’s been nurturing for over three decades. Oklahoma! was a masterpiece and an artistic, theatrical, musical, and cultural landmark from its opening night. Now at long last, in the year of its eightieth anniversary, it has the landmark recording it so richly deserves. This is the most important new recording of the year, and also the best.

[1] In Riggs’s original, the members of the community proudly declare their mixed blood heritage and are by no means uniform in welcoming statehood (at one point Aunt Eller declares, “What’s the United States? It’s just a furrin’ country to me”). Riggs seems to have developed a real sensitivity toward and sympathy for the place of women in the American Southwest. The playwright Carolyn Gage argues that his attempt to deal with what he saw as the hypermasculinity of American pioneers and settlers and the suppression of women is reflected in the chivaree that figures in the second act of Oklahoma!. There the ritual becomes a harmless tarnation-fun heckling of newlyweds. In the American Midwest of the nineteenth century chivareesconsisted not in “a playful hazing of newlyweds,” writes Gage, “but in a sanctioned, violent policing by gangs of young men over women who, in their eyes, were not sufficiently sexually subordinate.” As dramatized by Riggs, whose parents and grandparents Gage speculates “may have been witnesses, victims, and/or participants to the kind of chivaree depicted in the play,” Curly is dragged from the room as he yells to the men to leave his wife alone; before long both are forced to climb a ladder to the top of a tall haystack where, once the ladder is removed, the men scream and shout for the couple to put on what is in effect a pornographic show, urging them to have sex, as the men start lobbing straw babies at them. It’s only when Curly discovers the haystack has been set on fire (by Jeeter, the Jud Fry character) that the couple are spared further degradation. A subsequent scene makes clear Laurey will never recover from the trauma (Google “Carolyn Gage on Oklahoma!").

[2] Tim Carter in his magisterial Oklahoma!: The Making of an American Musical (1954, rev. 2020), provides a far more detailed, nuanced, and complex an account of the give-and-take between librettist and choreographer that challenges the accuracy of de Mille’s recollection. Dream ballets had almost two decades of antecedents in American ballets, operas, and musicals before Oklahoma!; but that said, the psychologically provocative eroticism de Mille brought to this one still qualifies as authentically innovative, as do also the moves, steps, gestures, and overall design of her choreography throughout the work.

[3] Unless you actually rewrite the play, as Daniel Fish did in the 2019 revival referenced earlier. There, it isn’t Jud who attacks Curly with a knife; rather, it’s Curly who with malice aforethought knifes Jud, killing him, while the makeshift court acquits the cowboy because he’s one of them and Jud is the dreaded, hated outsider. In case we miss the point, when Jud is stabbed, his blood spurts all over Laurey’s wedding dress. It’s curious that those who promote a more ostentatiously sympathetic view of Jud, in what in my view is a misguided attempt to make the play conform to contemporary attitudes as regards class, seem to forget that however unjustifiably badly he has been treated by the townspeople, he has nevertheless warned Curly, threateningly, to stay away from Laurey and twice attempts to kill him. He also threatens Laurey with abduction and rape—not explicitly, but the veil of his actual words is so thin as to be gossamer: “Yeah, we'll see who's better, Miss Laurey. Nen you'll wisht you wasn't so free with yer airs, yer sich a fine lady . . . Brought it on yerself. (In a voice harsh with an inner frenzy.)Cain't he'p it. Cain't never rest. Told ya the way it was. You wouldn't listen—." I would also point out that as realized in the book and the music and as he comes across in any good or better production, he’s a psychically damaged man, not a stock villain. (Something else too: Doesn’t Jud seem to know a little too many details about the sex-motivated murder/arson of a family who employed him before he came to work for Laurey?)

.png)