Le Dernier Message De Lester Young (The Last Message Of Lester Young)

Sam Records reissues the last Lester Young album with bonus 10 inch LP

In April 1958, Lester Young moved into the Hotel Alvin, a seedy hotel at the corner of Broadway and Fifty-Second street in New York City, which, because it was cheap, was home to many musicians. Lester owned a house on Long Island in which his wife and two children lived but the Alvin was directly across the street from Birdland, and that was where Lester wanted to be.

Lester wasn’t playing at Birdland or any of the other major clubs in Manhattan. His chronic alcoholism had worsened, affecting his playing and he was frequently drunk on the gig. An epileptic seizure had caused him to fall off the bandstand at Small’s Paradise and his explanation disbelieved, he had been fired for drunkenness. Word had spread and gigs became rare, mostly out of town, working as a single with local pickup bands. His manager dropped him as a client, and no one else would take him on. The first month’s rent at the Alvin was paid by Max Roach. Miles Davis and Sonny Rollins helped pay subsequent months.

Friends came to visit Lester at the Alvin. They would find him sitting by the window, drinking, listening to records, fingering his sax and looking down at the entrance to Birdland, watching the saxophonists arriving for work. So many of them—Getz, Sims, Cohn, Quinichette, all of the “Cool School”—were playing in a style that he had created. “They’re picking the bones while the body is still warm,” Lester groused. “When they come off and I go on, what can I play? Must I copy them?”

Unopened gin bottles, a dozen or more waited on the dresser. The empties were scattered about the room. Friends brought Chinese food but Lester didn’t eat, and the containers remained unopened. He became so thin that when Hank Jones came to visit, he saw covers on the bed and looked for Lester until he realized that Lester was under the covers.

He talked about death frequently and said, “As soon as I die, there’ll be some memorial albums out on me.”

Lester had become a sensation among jazz musicians when he made his first recordings in October 1936 with a small group contingent from the Count Basie Orchestra. At the comparatively advanced age for a jazz debut of twenty-seven, he was a fully formed musician with a revolutionary style. The dominant tenor sax style was Coleman Hawkins’ big full sound, playing arpeggios through the chords with a chugging rhythmic feel. Young showed a different way, playing with a lighter sound, emphasizing melody with a never before heard loose, floating swing.

Thad Jones described the impact Lester had, “All of us who heard him were totally in awe with this sound. It was so different and beautiful and so vital and it was like magic, like a magical tapestry that was continuing to be woven right before your very eyes and ears.”

Charlie Parker said, “I was crazy about Lester. He played so clean and beautiful.”

“In my mind, the way I play, I try not to be a repeater pencil, you dig?” said Lester.

Lester became famous not only for his playing on such Basie Swing Era classics as “Jumpin’ at the Woodside,” “One O’Clock Jump,” and “Lester Leaps In” but also as a “character.” Wearing his trademark pork-pie hat, he sat in the sax section with his horn tilted to the right, holding it nearly horizontal, disdaining big band symmetry. He spoke in a witty allusive slang of his own devising. “Cool,” “bread,” “I got eyes for that,” the rhythm section was his “three Mills Brothers’, when there were squares in the club he would say, “I feel a draft in here.” The bridge of a tune was “George Washington,” two policemen were “Bing and Bob,” a line of chorus girls were “sardines.” He called both men and women “Lady.”

John Hammond said, “Lester lived in a world of his own, communicating very little with anybody, speaking his own language. He chose to be different and he was.”

Eccentricity is the gentlest form of defiance.

Basie band drummer, Jo Jones said of Lester, “Very sensitive. Lester loved human beings. He did not understand how a human being could mistreat another human being.”

There was another tenor player in the Basie band, the very talented Herschel Evans who played in the Hawkins style. He and Lester complemented and competed with each other. Evans died of heart disease in February 1939 at 29 years old. Lester took the death hard. Jo Jones remembered, “He kept Herschel’s chair vacant with his hat and coat on it and every night (baritone saxophonist) Jack Washington would have to hold him because he’d get up and try to leave.” Lester, in an interview said, “We were nice friends but there wasn’t no bullshit or nothing. We got up on the bandstand and played, like a duel, you know. And then other nights we’d get along nice, you know what I mean? What I mean is coming through one’s instrument, you dig? He was a nice person. I was the last to see him die. In fact, I paid the doctor his bill and everything. So, he loved his instrument and I loved mine too. So, fuck you, fuck me.”

Lester walked in a mincing way and had a high-pitched voice. Gossip circulated that he was gay. Lester said, “If you want to speak like that, what the fuck? I give a fuck what you do, what he do, what he does, what nobody do? It’s nobody’s business.”

Lester wore slippers instead of shoes.

In January 1937, Lester, moonlighting away from the Basie band and doing session work, made his first recordings with Billie Holiday. Lester’s light but powerful swing and lyrical solos and obbligatos were a perfect complement to Billie’s singing, and together for the next four years, they elevated some very mundane jukebox tunes to great art and masterpieces of jazz. The musical intimacy between them was so obvious that many thought it had to be romantic as well. Trumpeter Harry Edison said, “Lester and her were closer than anybody. They were never girlfriend and boyfriend. People associated them with going together for years, but they were just absolutely good buddies.”

Billie gave Lester the nickname,-“Prez” because he was the greatest saxophonist.

Lester gave her the nickname,-“Lady Day.”

Billie said, “Yes, he was President and I was Vice President. I used to be crazy about his tenor playing, wouldn’t make a record unless he was on it. He played music I like, didn’t try to drown the singer.”

Billie and Lester also shared a favorite drink-“top and bottom” a concoction of half port wine and half gin.

In September 1944, Lester was in Los Angeles with the Basie band. An FBI agent came to the club where they were playing and told Lester that he had been avoiding the draft for a year and if he didn’t go to the draft board the next day, he’d be sent to jail for five years. Lester dutifully appeared, talking his hip talk, ‘Well voodaroony, I see you got Von Hangman’s eyes. So, I’m going to have to play my role.” He told the officers that he had been smoking marijuana for eleven years. They thought that he was playacting and judged him suitable for military service.

For the army this was a mistake, for Lester this was a tragedy. Emotionally and psychologically, he was completely unfit to be a soldier. He was also thirty-five years old in poor physical condition and an alcoholic who daily drank a quart of 100 proof liquor and smoked five or six marijuana cigarettes.

After basic training, Lester applied to join an army band but his superior officer didn’t like him, possibly because he had seen a picture of Lester’s white wife and assigned him to duty as a mess orderly. On an obstacle course, he fell and hurt his back, ending up in the hospital. There a neuropsychologist diagnosed Lester as “Constitutionally psychopathic manifested by drug addiction (marijuana, barbiturates), chronic alcoholism and nomadism.” He recommended disposition through administrative channels.

Lester wasn’t discharged but sent back to his unit. A few days later, an officer asked Lester what was wrong with him. Lester said he was “high” and showed him some pills. Lester’s locker was searched and some marijuana cigarettes and barbiturate tablets were found.

He was arrested, sent to the stockade, and tried for violation of military law. The trial lasted one hour and thirty-five minutes. Lester’s lawyer argued that the draft board knew that he used drugs and that he should never have been inducted. It was a strong argument but a futile one. Lester was sentenced to the maximum penalty of one year confinement in the military disciplinary barracks at Leavenworth. The summation of the verdict read in part, “The record of the accused, both civilian and military shows that he is not a good soldier. His age as well as the nature and duration of his undesirable traits indicate he can be of no value to the service without proper treatment and severe disciplinary training.” The army had made a mistake, but Lester would have to pay. That’s the rules. “So, fuck you, fuck me.”

Things can always get worse, worse even than Leavenworth, and Lester was sent to Fort Gordon, a military base in Georgia, in the Jim Crow south that Lester feared so much. What happened to Lester there is unknown. One could imagine but it’s easier not to. While at Fort Gordon, he became so desperate that he tried to run away but lost his nerve and came back when he saw guards with guns looking for him. The army finally released Lester two months early in December 1945.

He never spoke much about his time in the disciplinary barracks or said what had happened to him or been done to him while he was there. His comment was, “A nightmare, man, one mad nightmare. They sent me down south, Georgia. That was enough to make me blow my top. It was a drag.” Lester told his story in the only way he could--he wrote a tune “D.B. Blues,” and he played it on just about every gig.

A journalist who knew him for twenty years wrote, “His experiences in the southern army camps embittered, soured, changed him profoundly.” Harry Edison said, “The army just took all his spirit…” For the rest of his life, Lester withdrew even more into his own world and was subject to bouts of depression, suffered from insomnia, feared strangers, and sometimes began to weep for no apparent reason. Lester was still a great musician. He played well and people bought records and tickets, so, he-was just odd. It’s the music business. “So, fuck you, fuck me.”

Soon after his return to the jazz scene, Lester began a business relationship with Norman Granz that lasted until Lester’s death. In early 1946, Granz engaged him to be one of the stars of the first Jazz at the Philharmonic tour. The concept of JATP was an all-star jam session presented in concert halls. Lester played very well on the tour and established himself as a solo artist and star on the postwar jazz scene.

Throughout the 1950s JATP toured the U.S. and Europe frequently, usually featuring Lester. The pay was great, but the concerts soon devolved to a crowd-pleasing formula with long, loud, show off solos on the blues which invariably came to a climax with the saxes honking and shrieking. Lester, billed as “the original honker,” did his best but became increasingly disenchanted, preferring to play “pretty music” with just a little “tinkety-boom, tinkety boom” behind him. The large crowds, the fans who wanted to meet Lester Young, the famous oddball, hipster, the photographers, the press interviews all made him uncomfortable. The tours always made his drinking increase.

“Give me my three little rhythms and me---happiness. That’s four, the four Mills Brothers. That’s for me. I can relax better, you dig. I don’t like a whole lotta noise no goddam way. Take them trumpets and trombones and all that shit, fuck it.”

After a JATP tour in December 1955, Lester suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to Bellevue Hospital. Eating and forced abstinence from alcohol improved his health greatly. Norman Granz, realizing that the opportunity to record a peak form Lester might be short lived, got him into the recording studio on January 12 and 13, 1956. The resulting albums, Jazz Giants 1956 and Lester Young and Teddy Wilson are the last great stueedio recordings of Lester.

Then the End Began.

Soon he started drinking again but when he was relatively sober and eating, he still played wonderfully. Those occasions became increasingly rare. He didn’t have his own band anymore and with the exception of two Birdland Stars tours and a JATP tour, he played low paying club gigs as a single. Inevitably, his drinking became constant.

Johnny Griffin played a club gig with Lester in Chicago in November 1957 and said, “I couldn’t get him out of his hotel room. He was…lying in the bed listening to his old records that he’d made with Basie and his quartets….We didn’t play anything fast. Actually, I had to help him to the microphone to play. I mean he was really that weak and I couldn’t get him to eat…It was a sad experience to see him in a shape like that. It was not a happy experience to see a master deteriorating.”

On December 8, 1957, Lester appeared on nationwide TV on the CBS program, The Sound of Jazz. The telecast featured Billie Holiday and an astonishing array of musicians—Coleman Hawkins, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk, Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge, Lester and many others---all performing live. Lester was scheduled to play with Count Basie and Billie Holiday but he was so weak that it was decided that he should just play with Billie. Jazz critic, Whitney Balliett, one of the producers of the program wrote later of Lester, “He was particularly ethereal that day, walking on his toes and talking incomprehensibly.” Doc Cheatham, one of the musicians said, “There was a great feeling---all except Lester, who just kept to himself, sat apart. Lester was very quiet and sad that day. He didn’t have much to say to anybody. Even during the session, he was very solemn.” Were Balliett and Cheatham trying to say discreetly that Lester was drunk? Lester undoubtedly was.

The Sound of Jazz broadcast version of Billie singing “Fine and Mellow” with Lester playing a single twelve bar solo chorus is probably the greatest moment of jazz on film. After a voiceover of Billie talking about the blues, “Everything I do sing is part of my life,” she walks toward the camera and sits on a stool. Webster, Hawkins, Mulligan, Eldridge, Dickenson, all the horns, -except Lester, stand around her, waiting. The producers weren’t sure Lester could stand, so they sat him on a stool next to Billie.

Billie is still beautiful and seems reasonably sober. The network bosses had heard about her drug problems and told the producers to replace her with Ella Fitzgerald. They refused.

Roy Eldridge counts off and they begin. Billie sings the first verse of “Fine and Mellow” with an utter directness that is disturbingly intimate. “My man don’t love me, he treats me oh so mean.” She is telling you painful things about her life that you don’t want to hear. There is enough pain in life, no one wants to feel more. But she is a great artist and you can’t help but listen.

Tenor saxophonist Ben Webster plays the first solo and it is magisterial, displaying his brawny, slightly rough sound, playing beautiful melodic phrases. When he’s finished, Lester gets up and steps to the microphone. He seems steady on his feet and begins to play. His sound is tremulous, thin, more like an alto sax, but poignant and singing. He plays twelve bars of sparse blues melody that is a message from the private world of Lester. “It’s got to be sweetness, man you dig? Sweetness can be funky, filthy or anything---but which part do you want?” It’s the saddest blues. We all know the world doesn’t want sweetness. Lester has learned.

The camera cuts to Billie’s face. She is nodding appreciatively, smiling slightly, listening to Lester. She seems happy in the moment, happy that Lester is playing so beautifully, happy that they are musically intimate again after so long. She has missed the sweetness.

Soon after the television broadcast, Lester’s wife convinced him to go into the hospital. He was treated for malnutrition, alcoholism and cirrhosis. Lester was told that if he did not stop drinking, he could die at any time, probably within two months but two years at most.

When Lester got out of the hospital, he told musician friends that he wanted to move into the Alvin Hotel and look down on Broadway and at Birdland. It was arranged. A woman moved in with him but he stayed in touch with his wife and family out on Long Island.

He was a great man and a great artist. But he was a very sensitive man and he was hopeless. Some people are just that way. “So, fuck you, fuck me.” He began drinking again.

In June 1958, Lester was working infrequently when jazz critic and later to be founder of the Institute of Jazz Studies, Marshall Stearns, visited him and decided to help by convincing Birdland to feature Lester for a night to celebrate his thirty years in show business. Lester wanted a hundred dollars to play. Birdland would not pay more than fifty. Stearns made up the rest out of his own pocket.

Lester played well and Birdland brought him back for three more weeks which gained favorable publicity and brought in offers of work.

His last gig in New York was at the Five Spot in January 1959. Willie Jones, the drummer on the gig was to later say “(the) principles he taught me are: the philosophy of the spirituals, the musician as a philosopher and scientist, that we have made a major contribution to this country and we are Americans. Prez opened my eyes….He used to have a saying, ‘All the physicians come to hear the musicians.’ We should bring some beauty into the world.’”

In early 1959, Lester accepted an offer to play in Paris for eight weeks at the Le Bleu Note Club beginning in February. After finishing at the club, he planned to meet up with Granz’ JATP for a tour.

In Paris, his drinking increased and he stopped eating. He became so weak that he had to be helped down stairs. A fan who spent considerable time with Lester said later, “On certain evenings with Klook (Kenny Clarke) on drums, there were moments of great Lester, but apart from that there seemed to be a lack of resilience, a world weariness, a half voluntary resignation about him. He tells us that he’s been very ill and will die within a few months.”

Billie Holiday was in Paris doing concerts and singing at another club. She showed up a few times at Le Bleu Note and sang with Lester. One hopes that they were able to laugh and reminisce about the old days. They knew and understood each other so well, too well.

Lester was interviewed by a French journalist and spoke about the racial discrimination that he had experienced in France, “But it’s the same all over, you dig? You just fight for your life, that’s all. Until death do we part, you got it made.” It’s the same all over. “So, fuck you, fuck me.”

Norman Granz, probably having heard of Lester’s condition and fearing that there might never be another chance, contacted producer Eddie Barclay and asked him to record Lester in a studio. Barclay put together a first-class band to accompany Lester.

Kenny Clarke (1914-1985) is widely regarded as one of the creators of be-bop drumming and one of the greatest jazz drummers. Jamil Nasser, formerly known as George Joyner (1932-2010) was a superb bass player who, during a long career, worked in the groups of Ahmad Jamal, Randy Weston and Al Haig, and played on dozens of records. Jimmy Gourley (1926-2008) moved to France in the early 1950s and remained there for the rest of his life, playing and recording with visiting Americans and French musicians. Lester had played with Rene Urtreger (1934- ) on a tour in 1956 and he had become Lester’s pianist of choice when in France. His style, combining bop with Teddy Wilson melodicism, made him an excellent accompanist for Lester.

On March 2, 1959, Lester went into a Paris studio with the band and they recorded twelve tunes, eleven songbook standards and a Lester composed blues. All were mainstays of Lester’s repertoire and there are multiple recordings of all of them in his discography. The arrangements are simple and probably there was no rehearsal. The resulting album has the looseness and informality of a club set with the typical minor mistakes and momentary confusions.

At the start of the session, Lester was, if not sober, at least not so drunk that his playing was affected. He was however very weak and short of breath and well aware of his physical limitations. His unique and incomparable time feel and swing are unimpaired but he pares his playing down to the essential. The tunes are kept short, the two longest being slightly over four minutes. Lester, with three exceptions, only plays two chorus solos and the tempos are never much faster than moderate.

There are some beautiful moments on the session, mostly on the ballads and perhaps, not surprisingly, all the best music was recorded in the first half of the session. The first tune recorded was “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” one of the great songbook tunes, and Lester recorded a classic version of it on Jazz Giants ‘56. Here he plays the song at a medium tempo, surprisingly slightly faster than he did on the record. He plays the melody with poise and confidence and then plays a two chorus solo that is masterful in its use of parts of the theme to construct a flowing improvisation of pure melody without a note that could be edited. Lester’s clearly feeling in command of his horn and the music, and even plays a repeating rhythmic figure to push the band. It’s a very different interpretation of the tune than the exuberant one on Jazz Giants. Here his sound on the horn is thinner, more clarinet-like, less warm. Joy and exuberance have been replaced by extreme sensitivity to emotion and mood and his sparse playing creates a feeling of sorrowful reminiscence.

Next up is “Lady Be Good” which was recorded by Lester at his very first session and was the tune that made him immediately the most influential musician in jazz. Twenty-three years later, much has changed, but he plays the tune with the same deep, yet light swing that amazed the musicians in 1936. Lester’s solo stays close to the melody but sometimes that is enough and, prodded by Clarke’s superb drumming, he starts swinging hard in the second chorus. They trade eights at the end and Lester matches Clarke with his hardest swing and most aggressive playing of the session.

Third is “Almost Like Being In Love,” and it has some of the most self-assured playing by Lester on the session. Nasser and Clarke lay down a solid but not overly aggressive groove, and Lester plays a wonderful solo of his trademark continuous melody with some rhythmic playfulness and a quotation of the theme near the end.

“Three Little Words” is played fastest of all the tunes and Lester, buoyed up by Clarke’s drumming, swings easily. His solo is a masterful example of spontaneous composition and is structured around a five-note figure that he repeats, altering it rhythmically each time.

“I Cover The Waterfront” is another frequently played Lester favorite, first recorded in 1956 by him with Nat King Cole. His solo is two choruses of singable, improvised melody, ending with some phrasing that Billie Holiday had used on her classic version of the tune. It’s hard to understand why, after Lester’s wonderful playing, Kenny Clarke and Lester traded fours to take the tune out. The aggressive drum solos break the delicate mood Lester has created.

One of Lester’s long-time features was “I Can’t Get Started.” It’s the sixth tune recorded and here he plays the melody gorgeously with a soft, breathy tone, sounding vulnerable and hesitant. As he plays, his sound gets stronger and he plays some powerful, bright high notes midway in his solo and then just plays pretty melody until he ends with a nice tag. It’s a touching performance with a haunting, melancholy feeling that only Lester could express.

We are now at the second half of the session. What little strength Lester had is gone. Possibly, a break was taken and he returned from it, worse for the wear. In any event, from this point, Lester is uncomfortable with even moderate tempos and seems to be consciously limiting his musical ideas to what he knows he can play. “Indiana,” is not a complex tune but it took five tries to get an acceptable take. Lester plays the melody almost straight for the first chorus and then for the second he plays short phrases, seemingly unsure that he can sustain long melodic lines.

The first chorus of his “Pennies From Heaven” solo is once again a near recapitulation of the melody and on the second he plays some disjointed, floundering phrases.

Lester was one of the greatest blues players, and everything he played, even ballads, was tinged with blues feeling. "A.B. Blues" is a tune very similar to "D.B. Blues" but he plays it a bit slower and without the driving, R&B style swing that he usually mustered for "D.B. Blues." The first chorus of his solo has some blue notes and notes that would be honks, but Lester lacks the breath. The second chorus begins with a near wail and has a flowing low register melody, followed by some beautiful phrases, all played with that amazing, relaxed Lester swing. But on the third chorus he seems to lose focus and energy and is unable to follow up on the momentum he had developed in the second.

Lester’s solo on “Lullaby Of Birdland” is for him formulaic and he seems to be playing phrases from memory but his rhythmic genius makes even an uninspired solo enjoyable.

“There’ll Never Be Another You” is a beautiful tune that Lester in his prime always played movingly. Here, the tempo again seems a bit too fast for him. He plays some lyrical, whispering melodic ideas but seems to lose his train of thought and plays an inappropriate, cliched “rebop” rhythmic figure to fill out and make a rather abrupt end to the chorus

“Tea For Two” was the last tune recorded and is taken too fast for an obviously exhausted Lester. In his solo, he struggles to keep the tempo and again resorts to playing short phrases and long notes to fill space.

The album that resulted from the session, Le Dernier Message De Lester Young (The Last Message of Lester Young) is not a masterpiece. It’s far from Lester’s best music. In Paris, in the recording studio, a physically diminished Lester used the strength he had left to share the private world that was his music. It had always required great strength to be Lester and live in our world and even more strength and generosity and courage to share his world and its beauty with us. Now he had so little strength left.

The End of the End Begins

After recording The Last Message, Lester grew even weaker and sicker. In considerable pain, he decided to cut short his stint at La Blue Note, cancel his appearance on the JATP tour and fly home to New York on March 14.

On the flight home, he began to bleed internally and vomit blood. At the airport in New York, he refused to go to the hospital and insisted that he be taken back to the Alvin. Once in his room, he drank a bottle of vodka and some bourbon and sat by the window, looking down at Birdland and listening to records. He died at approximately 3 am on Sunday March 15, 1959.

The end.

The Lester Young Memorial Album Volume 1 was issued a few months later. “So, fuck you, fuck me. “

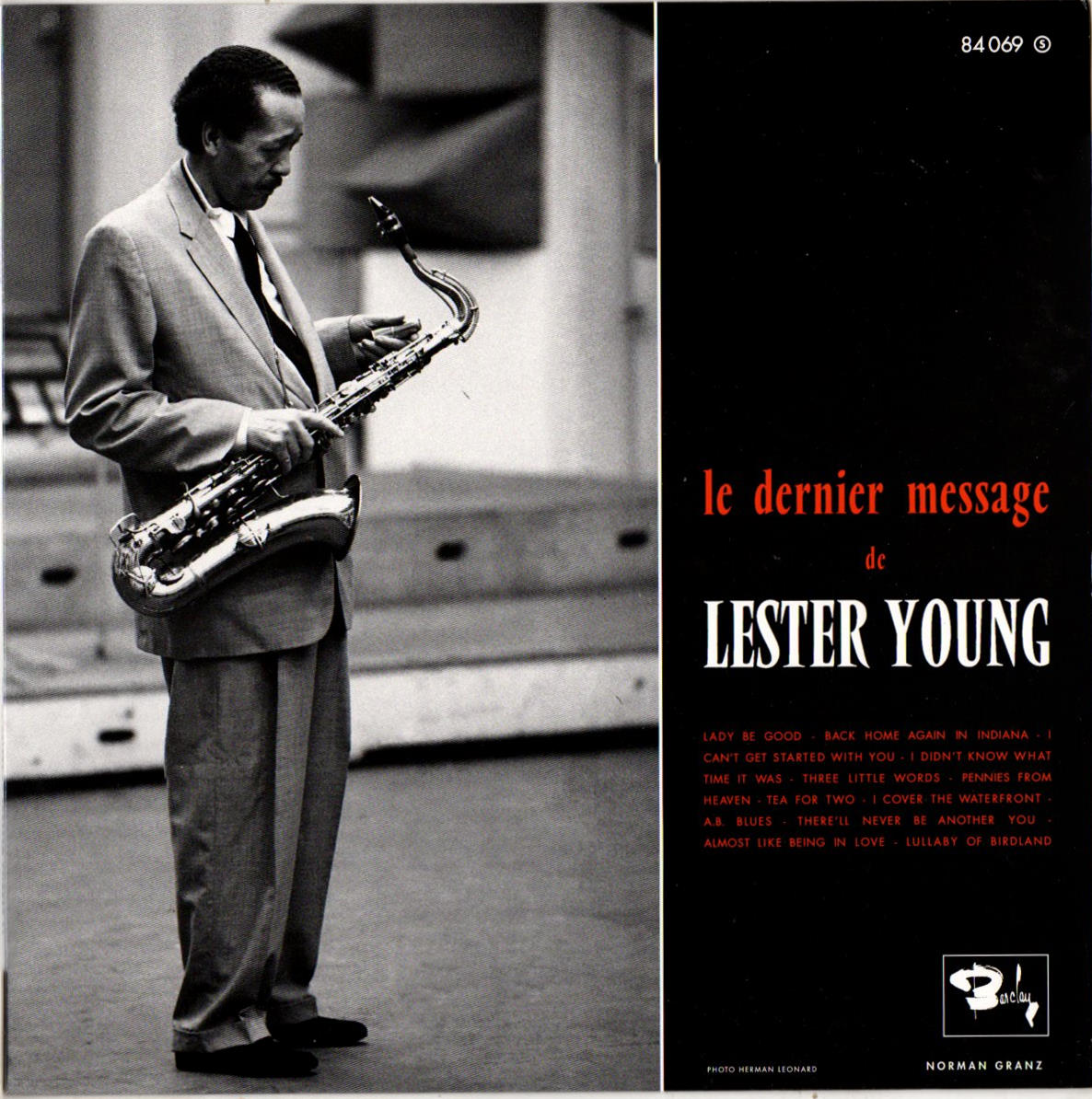

Le Dernier Message De Lester Young was issued in France in 1959 by Barclay and in 1960 in the U.S. by Verve as Lester Young In Paris. Sam Records has reissued a near, except for licensing info, facsimile of the Barclay edition. Like all Sam Records, the cover and artwork are gorgeous. The photos by Herman Leonard are ultra sharp and appear to be from original negatives. The photo on the front cover of an emaciated Lester in the studio wearing his slippers is beautiful but heartbreaking. The cover is flipback, glossy, superbly printed and a wonderful piece of phonographic art. Inside is another 11x11 photo of Lester on high quality paper, taken by JP Leloir..

The records—limited to 2000 copies—pressed by Optimal in Germany using metal parts produced by Pallas, duplicate the original Barclay labels and the color shades are correct. My LP is glossy, lustrous, deep black and unblemished. Side 1 played very quiet. Side 2 played with some occasional light surface noise during the first ten minutes.

I have never heard a Barclay pressing of Le Dernier Message, but I own an original Verve copy of Lester Young in Paris. I preferred the Sam reissue to my Verve. The Sam was smoother and more well balanced tonally with a “tubey” midrange. Bass was a bit deeper and more melodic. The Verve was harsher tonally with a thinner midrange. Bass was a bit thumpy compared to the Sam. Most importantly, Lester’s sax was fuller, more dynamic and 3D mono on the Sam.

Also included with the LP is a one sided 10 inch 33 rpm record of “D.B. Blues” recorded March 11,1959 in a studio for French radio. This is the first issue of the track. Unfortunately, Lester sounds very drunk and his command of his horn is faltering. I’m not sure I’m glad that I heard the track. I doubt I’ll play it again.

Clearly, considerable effort has been expended by Mr. Fred Thomas, owner of the Sam “one man label” to produce a record that is a beautiful objet d’ art. He has succeeded and at 35 Euros (app $37.50) Le Dernier Message De Lester Young is a highly recommended purchase.

1. Many of the quotes above are from You Just Fight For Your Life, an excellent biography of Lester Young, by Frank Buchmann-Moller.

2. The Columbia LP, The Sound of Jazz, was recorded on December 5, 1957 at a rehearsal for the TV broadcast. The version of “Fine and Mellow” on that LP is not the one discussed above.

Copyright by Joseph W. Washek 2023 and all rights are reserved.

.png)