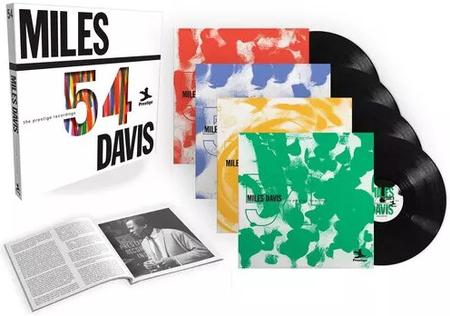

Miles Davis in 1954

A grand 4-LP box set marking the great trumpeter's pivotal year

When jazz aficionados see the phrases Miles Davis and Prestige Recordings in the same sentence, they think of the “marathon sessions” of 1956, where the trumpeter and his quintet (known in retrospect as his 1st Great Quintet: John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones) blazed through four albums’ worth of material (released over the next few years as Relaxin’, Steamin’, Workin’, and Cookin’) in just two days (May 11 and October 26), to complete his contractual obligation to the small indie label before hitching his rising star to Columbia Records.

But this boxed set, issued by Craft Recordings, is something else. As suggested by the title, Miles 54, it contains all the tracks that Miles recorded for Prestige two years earlier—specifically, the 20 tracks laid down, with various bandmates, over five sessions from March to December of 1954. The ’56 quintet sessions established Miles Davis as a great musician and an innovative bandleader who changed the sound and shape of jazz (and would do so again several times over). Miles 54 documents the year when Davis first found his sound and pivoted toward greatness.

The first of the five sessions, recorded March 15, has Miles just returning to the New York jazz scene, having regained his strength after kicking a heroin habit. Had this marked the end of his road—if, say, he’d reverted to the needle and soon after died of an O.D.—he would not be widely remembered today. Still, these three tracks, which were originally released as a 10” LP (and later combined with the four tracks of the April 3 session into a 12” album called Blue Haze), are pleasant.

It's with the April 3 tracks that the Miles we all know begins to take shape. First, he discovered the cup mute, which coated his horn with a crisp burnished tone, and he keeps it fastened to the bell throughout. Second, his pianist and bassist, Horace Silver and Percy Heath, had clearly picked up some confidence and verve between the two sessions. Third, drummer Kenny Clarke, replacing Art Blakey, added some crisp brushwork to the mix.

On April 29, Lucky Thompson and J.J. Johnson joined in, on tenor sax and trombone, for what was properly called an “all-star” band, blowing a blend of hefty blues and complex harmonies that had never before quite been heard. As the pianist-critic Dick Katz said of the session (quoted in Dan Morgenstern’s liner notes to this boxed set), “It is as if they all agreed to get together to discuss on their instruments what they had learned and unlearned” over the previous decade—“what elements of bop…they had retained and discarded.”

On June 29, the two horns were busy elsewhere and Sonny Rollins filled in on tenor sax, furnishing a few of his own compositions (“Airegin,” “Oleo,” and “Doxy”) as well as his gruff tone and whirlwind improvisations. Rollins gave Miles an idea of what sort of tenor sax sound he was seeking and led him to hire John Coltrane a couple years later. (Rollins by then was a leader in his own right.)

Finally comes the coup de grace, the masterpiece of the box, the Christmas Eve session, with Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson joining Heath and Clarke. (When this session was released as an album in 1959, its title, Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants, was no hype.) It consists of just four songs—Jackson’s “Bags’ Groove,” Monk’s “Bemsha Swing,” Davis’ “Swing Spring” (one of just three Miles originals in the box), and Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” including two takes of the first and last songs (more about which later). This session is a jaw dropper; it was at the time and still is.

The box set as a whole is not a “best-of” Miles Davis collection. Even for the era, you’d do better with the Great Quintet albums recorded two years later. Still, these sessions are crucial for understanding how Miles Davis—and, in turn, how jazz—evolved in the middle of the 1950s, how it became modern jazz as we now know it. And the best sessions from the box—the one with Sonny Rollins and the Christmas Eve finale with Monk and Jackson—are extraordinary by any standard.

Now for the sound (mainly very good news) and Craft Recordings’ packaging (handsome but in many ways not good news). The April 3 session marked engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s debut (certainly with Miles, probably with Prestige), and the contrast with the session before (though it sounds good, especially for the era) is striking. The drums are crisp and dynamic, the bass thumpingly clear and precise, the trumpet golden, the other horns billowing brass and air, and the piano is percussive and blooming—in many ways, fuller- sounding than the pianos on many of RVG’s later albums.

Unfortunately, in some of the later ’54 sessions, Van Gelder ladled on some artificial reverb, maybe to make his parents’ living room sound more like a club or concert hall. It’s not annoying—the sound throughout the rest of the box is still very good, especially Jackson’s ringing vibes on the last session—but he could have done without the echo.

Last year, Electric Records Company released one of the these albums, the Miles Davis All-Stars’ Walkin’ (the session with J.J. Johnson and Lucky Thompson), and it sounded terrific. It’s a great tribute to report that Craft’s pressing of those tracks sounds just as good (for a fraction of the price). As for comparisons with other vinyl reissues, I have only Analogue Productions’ two-LP 45rpm pressing of Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (part of its Fantasy 25 series), and, perhaps because it is 45rpm, it sounds better: all the instruments are richer in their harmonic overtones. Still, the Craft’s sides of this material are excellent. Due to the compilation nature of this set, the cutting sources were 192/24 bit files. To cut from tape would have required cutting up masters to assemble.

Now for some complaints. The booklet should have cited the titles of the albums where the tracks were originally laid down. (It mentions none of them.) It lists all the musicians involved, but you have to read the liner notes to learn (if you didn’t know already) who is playing on which tracks. It also would have been useful to group all the pieces from a session onto the same side or the same slab of vinyl instead of dividing them up (for instance, putting three tracks from one session and one track from the next session on one record, then the remaining tracks from the second session on the next record). There is also a serious mistake: On Disc 4, the listing for the two tracks of “The Man I Love” are reversed; the booklet says Take 1 is first, then Take 2. In fact, it’s the other way around. This isn’t a small point. At the start of what is really Take 2, we hear the famous exchange where Miles tells Monk not to solo this time and Monk complains about it. This is because Miles didn’t like Monk’s soloing, which was rather erratic, on Take 1. If you think Take 2 is Take 1, you might wonder if there was a take before Take 1. *

Finally, there is a credit problem. The booklet properly notes that Kevin Gray cut the lacquers but says that Paul Blakemore mastered the tapes. In fact, Gray mastered, as well as cut, these LPs from the original analogue tapes. Blakemore mastered the digital versions (on CD and streaming). Gray deserves full credit for a splendid job.

*Turns out, upon inspection, I was wrong about the labeling of “The Man I Love,” Take 1 and Take 2. The labeling is right. (Miles wasn’t telling Monk not to solo, but rather not to comp behind him.)_F.K.

**You may have noticed the credits changed from AAA to AAD and mastering from Kevin Gray to Paul Blakemore. FK did check with KG about this and he mistakenly told FK it was cut from tape. He'd confused this project with an OJC. Mistakes happen. We correct them when they are discovered_ed.

.png)