Ornette Coleman’s Divisive Blue Note Era

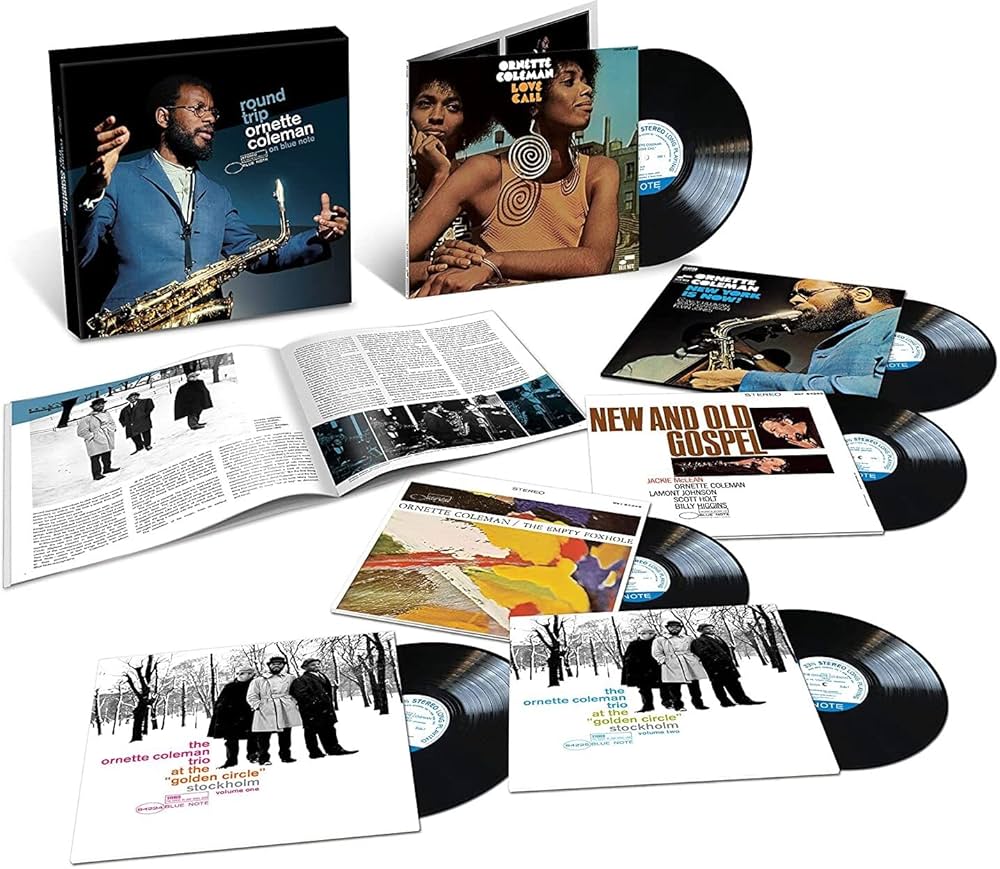

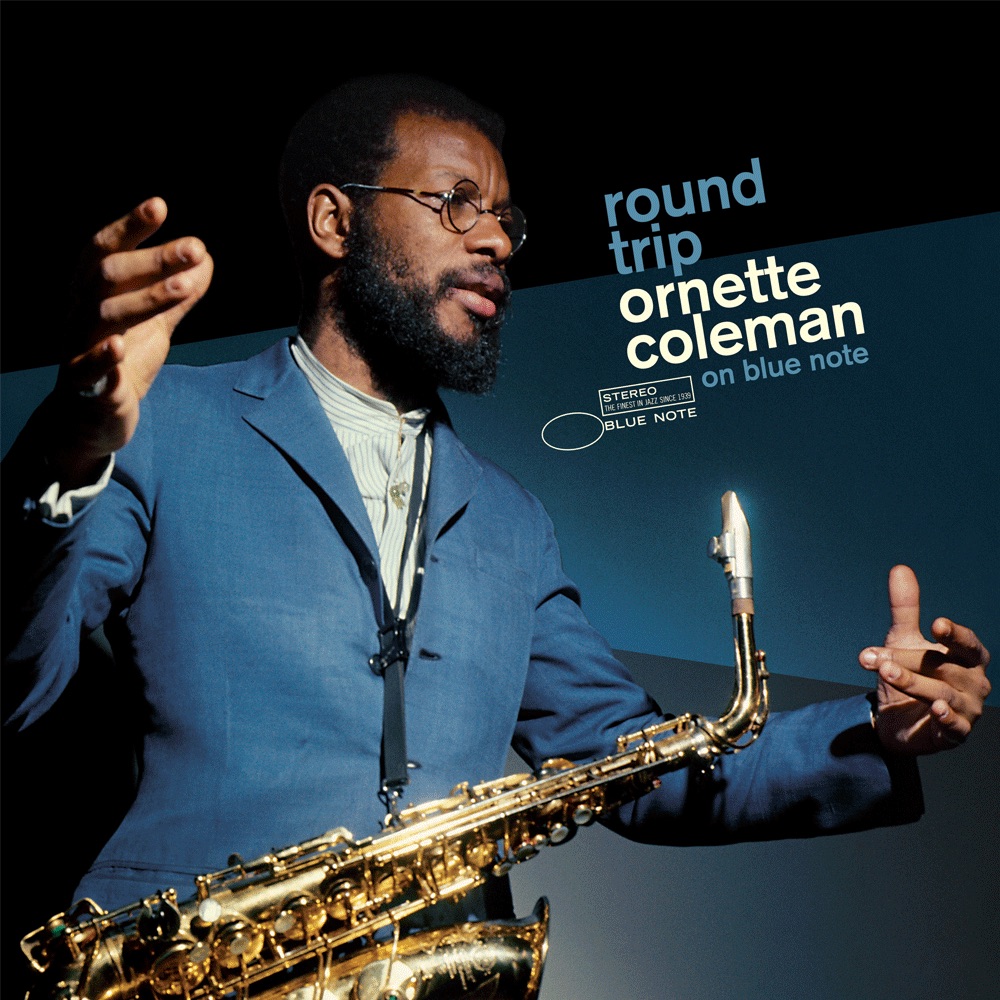

Tone Poet series box set ‘Round Trip: Ornette Coleman On Blue Note’ is a first-class document

Binging Ornette Coleman’s discography, from his early Contemporary recordings to his historic Atlantic period then the Blue Note releases and beyond, is a truly enriching experience. One hears how his sound developed over his first decade of recordings, how certain musicians fit in his groups, how he started exploring other instruments beside his usual alto sax. Last year, Blue Note’s Tone Poet series released Round Trip, a 6LP box set containing his mid-late 1960s Blue Note recordings, cut from the master tapes by Kevin Gray. Perhaps it scared some traditionalist jazz audiophiles, because I got my copy from PopMarket (one of Alliance Distribution’s direct-to-consumer branches) for $115, half of the $230 list price (that sale is over, but there are still good deals on this). Since I’ve recently spent considerable time with Ornette’s discography, Michael Fremer asked me to review the set.

In August, I wrote about Genesis Of Genius, Craft Recordings’ box set of Ornette’s first two albums for Contemporary Records. Between those records and Cecil Taylor’s one Contemporary LP, it seems as if the label’s founder and producer Lester Koenig wanted to support avant-garde musicians, but not the ideas that made them special. Ornette’s Something Else!!!! and Tomorrow Is The Question! sound very stilted and, contradictory to his musical philosophy, the former even pairs him with a pianist.

He then signed to Atlantic, and from 1959 to 1961 recorded his most renowned work. His usual quartet setting had himself and trumpeter Don Cherry at the front, with either Billy Higgins or Ed Blackwell on drums and Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, or Jimmy Garrison on bass. The Atlantic era has undeniable gems—The Shape Of Jazz To Come, This Is Our Music, and Free Jazz especially—and some comparative duds. Ornette On Tenor, the last of the six core Atlantic LPs, is merely okay, and of the outtakes released on later LPs (The Art Of The Improvisers, Twins, To Whom Keeps A Record), there’s only about one record worth of good material amidst obvious scraps. Those extra bits occasionally offer a fascinating look at how he developed certain ideas (anyone who likes Free Jazz should hear “First Take” from Twins), but it’s mostly for completists.

By the time he fulfilled his Atlantic contract, Coleman was tired of exploitation and racism across all aspects of the music industry. He quit for two years, during which he taught himself trumpet and violin, then reemerged with a trio of himself, bassist David Izenzon, and drummer (and Fort Worth high school classmate) Charles Moffett. This lineup primarily performed live, and only went into the studio (expanded to a quartet with Pharoah Sanders) when director Conrad Rooks commissioned music for his film Chappaqua. Rooks eventually didn’t use the music, released in 1967 as Chappaqua Suite on CBS France, but Ornette now had enough money to tour Europe for the first time.

This was the mid-60s, when Blue Note signed a lot of avant-garde players. These records didn’t sell back then, and maybe they still don’t sell much now, but this material remains exciting. Blue Note signed Ornette, first releasing two albums from the trio performances at Stockholm’s Golden Circle club. Both volumes of At The “Golden Circle” Stockholm are absolutely electrifying. Ornette goes wild, Izenzon’s bass is an assertive force that knows when to advance and recede, and Moffett is frenetic. By Ornette standards, Volume One might be fairly accessible from a post-bop perspective, but it’s still prime Ornette and therefore isn’t straightforward anything. “Snowflakes and Sunshine” on Volume Two finds him playing violin and trumpet. His violin is screechy and thin, but his trumpet, although not traditionally precise, has a nice liquid quality. At The Golden Circle is top-tier Ornette Coleman, and the recording by Rune Andreasson is off the charts insane. It’s a small club so there’s plenty of microphone leakage and, as a result, startling realism. I have quite a few Music Matters/Tone Poet/Blue Note Classics reissues, and this is one of the best. The entire Round Trip box set is worth it just for these two records. (Music: 9 // Sound: 11)

Perhaps what’s most striking about Ornette’s more avant-garde work is its total lack of pretension. He’s not outright expecting you to get it, rather encouraging you to comprehend and appreciate it on your own terms, on your own time. This music was for everyone, able to be enjoyed and played by anyone who put in the effort. That included his then-10-year-old son Denardo Coleman, drummer on 1966’s The Empty Foxhole, Ornette’s first studio date for a label since his last Atlantic session in 1961.

Denardo’s drumming here remains controversial. His timing is flawed. He plays too many fills, especially on the ballad “Faithful” or the blues-based opener “Good Old Days” when I wish he’d made more room for bassist Charlie Haden. Still, Denardo isn’t bad, and with Haden as musical anchor, he communicates well with his father’s wilder explorations. Ornette plays alto on half of The Empty Foxhole, and violin or trumpet on the rest. I don’t mind his trumpet playing. His violin on “Sound Gravitation” is tolerable on lower notes and gets more grating as he moves up. The Empty Foxhole isn’t perfect, but Ornette’s music wasn’t about perfection; no matter the execution, it philosophically makes sense. Rudy Van Gelder’s recording sounds excellent, especially without the sonic variable of a piano. (Music: 7 // Sound: 10)

Ornette Coleman rarely played as a sideman or with a pianist, yet he plays trumpet on Jackie McLean’s New And Old Gospel with pianist LaMont Johnson, bassist Scotty Holt, and Billy Higgins on drums. McLean, a hard bop player who followed the trend towards the avant-garde, wrote the “Lifeline” suite on side one. His ambition is admirable, but it sorely lacks cohesion and the transitions are unnecessarily jarring, as if the sections were haphazardly jammed together. Side two’s Ornette compositions are better organized, but this session is more interesting than it is good. McLean pushes his alto sax into territory where he doesn’t really know what he’s doing, and Ornette whines and farts his way around on trumpet. Higgins is great as usual, though I’m not sure what to make of Johnson’s piano. The parts, both instrumentally and structurally, are there but they don’t exactly work. Rudy Van Gelder’s recording is quite excellent, though the artificial reverb is more obvious than usual. Worth a listen if you adjust your expectations. (Music: 6 // Sound: 9)

The last set of records here, 1968’s New York Is Now! and 1971’s Love Call, come from two 1968 sessions engineered by Dave Sanders at A&R Studios. Ornette returns to a quartet setting, this time with tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Elvin Jones. Garrison played with Ornette before his stint with Coltrane, and the two have more synergy here than on the earlier collaboration (Ornette On Tenor and its associated outtakes). Redman doesn’t provide the frontline contrast like Don Cherry on the Atlantic titles, and Elvin Jones’ playing feels a little too embellished for Ornette. New York Is Now! is the better of these records; Love Call probably has the set’s “freest” stuff in the usual sense of the word, but the release feels like an afterthought. The sound on these is noticeably more claustrophobic than the Stockholm sets and the Van Gelder recordings. (Music: 7 // Sound: 8)

There’s a consensus on Ornette’s Atlantic recordings—whether or not you like them, they’re at least Important—but with his Blue Note work, it’s as if everyone’s hearing an entirely different set of records. Although not every experiment pans out, the failures are worthwhile in their own way. For example, New And Old Gospel isn’t very good, but you’ll listen a few times in hope of figuring out why it’s not very good. That is the lasting power of Ornette Coleman’s music.

As usual, the individual records in Round Trip: Ornette Coleman On Blue Note come in laminated tip-on jackets, with a laminated slipcase and 16-page booklet rounding out the package. The archival photos are fascinating and Thomas Conrad’s liner notes are informative. The six 180g LPs pressed at RTI are flat and quiet. Get it if you’re an Ornette fan, or a curious listener if the price is right. The Golden Circle LPs are the true highlight, but you’ll want the whole thing anyway.

.png)