Ray Charles’ ‘Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music’: Sorry, Stick With The Original

DYNAMIC COMPRESSION DOES NO FAVORS FOR THE GRAMMY HALL OF FAME-WINNING CLASSIC

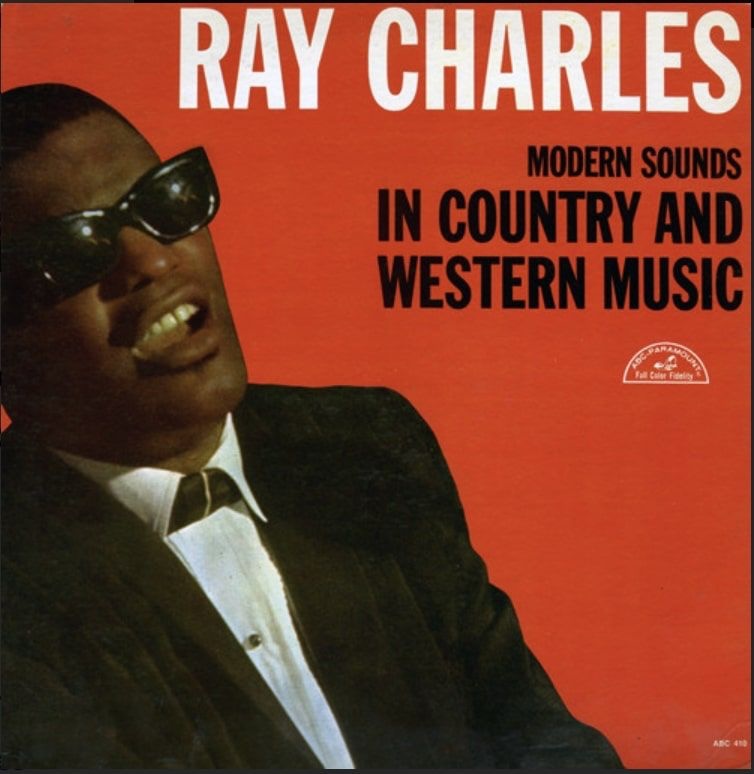

As a record, Ray Charles’ Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music holds up just fine. But as an idea? It may be one of the most beautiful we ever had.

The story is a familiar one, as far the American musical mythos is concerned: Back in 1962, at the flashpoint of the civil rights movement, Charles recorded 12 standbys originally by Hank Williams (“You Win Again,” “Hey, Good Lookin’,”) Don Gibson (“I Can’t Stop Loving You”), and other luminaries of the tradition.

Six decades before Cowboy Carter launched a thousand thinkpieces — and won the golden gramophone for Album of the Year — Charles courageously demonstrated a self-evident truth: country music is Black music is country music.

Of course, Charles is one of the singers of all time, and he had three top-shelf arrangers on board: Gil Fuller and Gerald Wilson for the big band charts, and Marty Paich for the string orchestra. But for all these qualities, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music can be a bit of a stodgy listen — a gilded lily.

All respect to Fuller, Wilson, and Paich — and Charles, who’s said to have closely guided them in the arrangement process. But the (over)use of call-and-response is a bit draining, as is the era’s omnipresent use of angel-choir backing vocals: we’re all here for Ray, but to get to him, we have to maneuver around a bit of clutter.

Despite all this: listening to an original vinyl pressing of Modern Sounds on Tracking Angle editor Michael Fremer’s elephantine system, I was surprised by how much closer I felt to Charles, as he sang these gorgeous ballads through his nose. He sounded tenderly human. In short, there was a real presence there — one missing from innumerable streams over the years.

Despite all this: listening to an original vinyl pressing of Modern Sounds on Tracking Angle editor Michael Fremer’s elephantine system, I was surprised by how much closer I felt to Charles, as he sang these gorgeous ballads through his nose. He sounded tenderly human. In short, there was a real presence there — one missing from innumerable streams over the years.

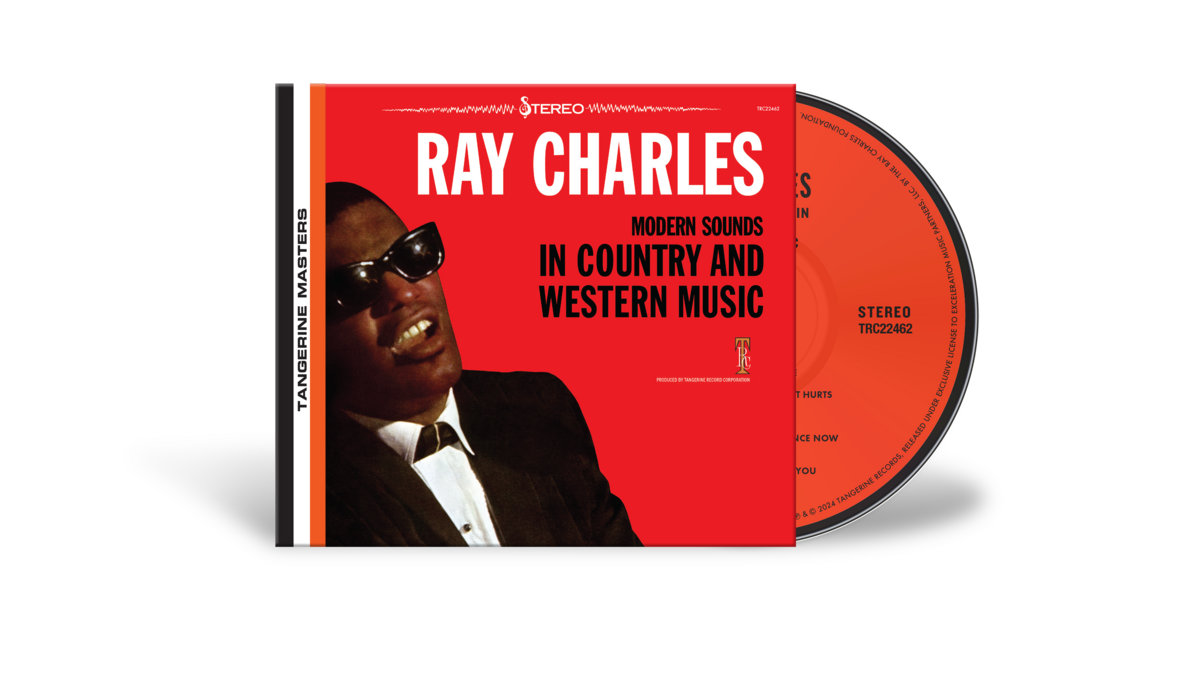

Which brings us to this 2024 remaster on Charles’ label, Tangerine Records, with the blessing of his estate — released last September via vinyl, CD, and digital. Finally, I thought. A fresh version! A record that could use a leg up could finally get it.

Instead, when I popped in the CD — the label didn’t send us vinyl, but you’d better believe it sounds like this too — I was severely disappointed. Plumped with excessive bass — with a similarly contrived top-end to the soundfield — everything in the middle seemed to coagulate. (Blame dynamic compression.) Charles was no longer running the show; he seemed lost in the sauce, on a record where he can scarcely afford to be.

I’m left with so many questions. It’s called Modern Sounds, right? So why does it sound less modern today? Doesn’t this work — of such historical import, not just musical — deserve a nuanced, clarifying touch? Why did the estate think this should fly? Is this how future generations should hear this? Who benefits from degrading it to the aural equivalent of a weekend at Grandma’s house?

The answer is nobody; we all lose. Grab an original pressing. Sorry, Ray. None of the 20th century’s preeminent musical figures deserve a rush job like this, least of all you.

.png)