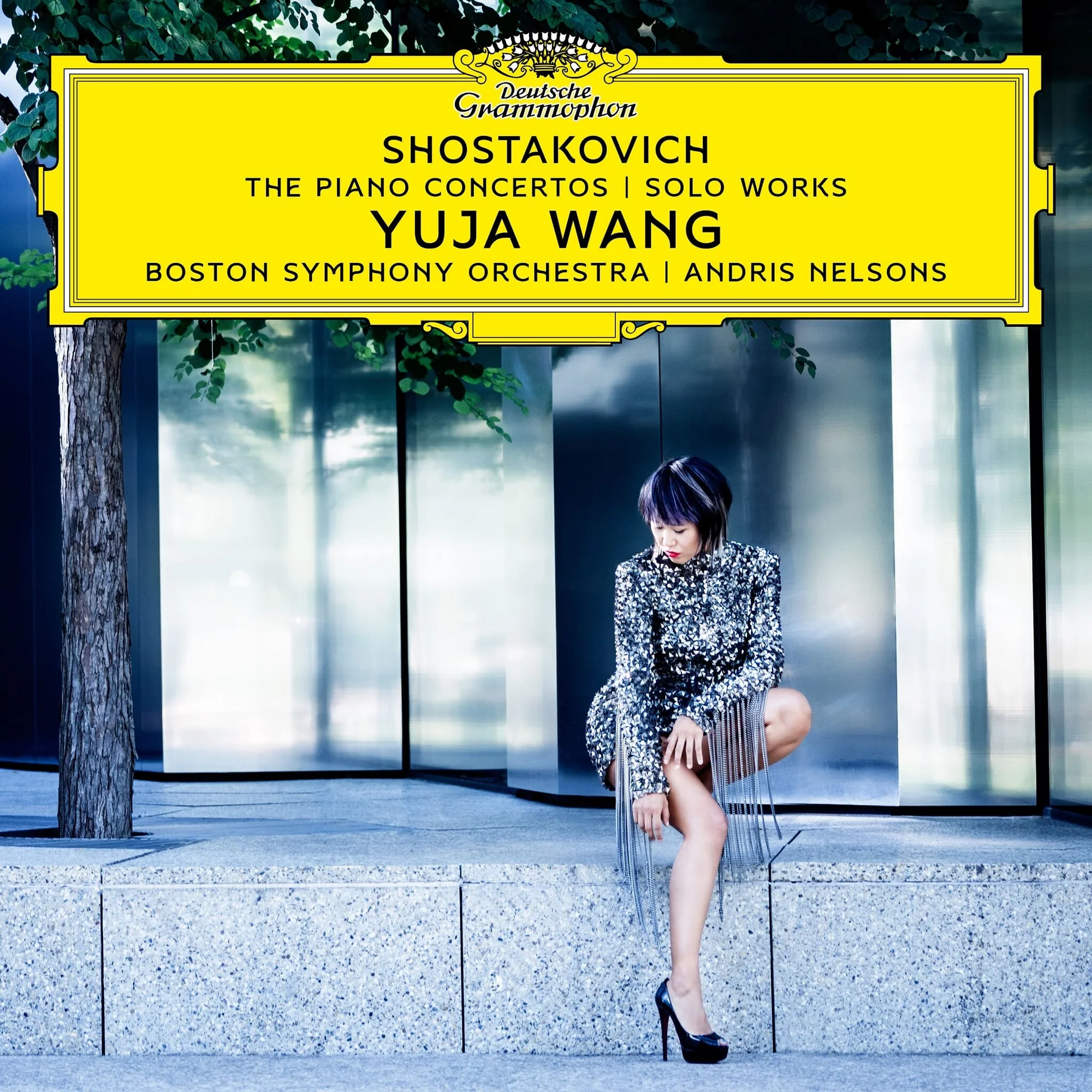

Scintillating Shostakovich with Superstar Pianist Yuja Wang in Audiophile Sound

Legendary Producer/Engineer Shawn Murphy brings the heat

.jpeg) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 - 1975) in the 1930s (Photo: N.V.Lukyanova)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 - 1975) in the 1930s (Photo: N.V.Lukyanova)

Okay, so I knew from other reviews of this release, and the general buzz that accompanies all things Yuja Wang, that this was going to be, at the very least, a really good listen.

But then I dropped the needle (as we used to say back in the day), and…

In the words of the immortal Bette Davis in All About Eve:

“Fasten your seatbelts. It’s going to be a bumpy night.”

From the opening kinetic flourish of the First Piano Concerto this thing takes off like a rocket, and the fireworks keep coming for all 50 or so minutes. Yes, I’ve loved these concertos going back to my teenage years, so I knew what was coming, but still this thing pinned back my ears and kept them there for the duration.

My second Big Gasp came as the full force of Ms. Wang’s piano sound hit me in the solar plexus. The bass is so rich and vast you feel like you can literally sink into it, even as you’re still taking the curves at 150mph.

I immediately cast an eye over the credits to see who had recorded this thing, and thus all was revealed. “Produced and Engineered by Shawn Murphy”, only one of the tip-top sound Meisters of the last several decades (please read the hyperlinked Shawn Murphy interview originally published in The Tracking Angle magazine in 1995_ed.

Shawn Murphy

Shawn Murphy

But he is known primarily for his work in film soundtracks and a host of film soundtrack records (seek out the exquisite John Barry retrospective, Moviola, and any number of superb John Williams outings). And Mr. Murphy has liberally sprinkled tinsel town magic all over these recordings. They are big, fat, glittering, rich, detailed, warm, precise, 3-strip Technicolor widescreen, and all the yummier for it. The warm acoustic of Boston’s Symphony Hall, and the effulgent orchestral sound of 1970s BSO that I (and my colleague Michael Johnson) have been relishing on a slew of the best sounding Original Source vinyl reissues is here given a digital update that retains all the positives and adds its own thrilling new spin.

That piano sound - I just couldn’t get over it. It’s enormous, like you’re actually in the piano, and yet somehow the orchestra is still there, laid out precisely in the soundstage. Okay, so maybe the piano isn’t entirely natural in its proportions, but who the hell cares when it sounds this good, this exciting, and, under the fingers of Ms. Wang, supernaturally virtuosic.

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang

Yup, it’s getting to a point now where I’m starting to wonder if Ms. Wang - like Robert Johnson and Doktor Faustus before her - didn’t come to a little arrangement with Mephistopheles at the crossroads. Her playing is so supremely virtuosic that the most demanding of passagework is almost ho-hum in its perfect execution. Which leaves her free to communicate the music under the cascades of notes. And communicate the music she does to the max. The thing is that her mastery of the keyboard is so complete, her finger and arm strength and powers of articulation so all-encompassing, that she gives the impression she doesn’t even have to think about the formidable technical challenges of actually playing this stuff. She just does it - like breathing. In music like this, with cascades of notes, you hear all the layers so clearly, yet she is also to find the musical line throughout. No effort whatsoever. And with that ease comes pure musical and emotional communication: direct, no fuss - and utterly compelling.

This being the classical music world, there have always been those all too ready to dismiss young players possessed of such stunning preternatural talent and virtuosity as “shallow”, great at dashing off a ton of notes, but lacking in depth. They’re especially prone to dismiss young female players whose looks etc. are pushed by the marketing folks to sell records and concert tickets. (If you care to do so, you can take a really deep dive online into the whole aspect of the Yuja Wang phenomenon that has nothing to do with her music making).

But Yuja Wang is the real deal, and SO much more the real deal than her fellow, older Chinese keyboard phenom Lang Lang, whose recordings I gave up on long ago. He is just so annoyingly ingratiating, and thus cloying, working over every phrase like it’s as interesting as he thinks he is. (His contemporary Yundi Li, another DG artist, is far more genuinely beguiling and substantial).

Not only would I recommend this record to the fervent collector, I would also recommend it to the classical newbie. It is such easily attractive and engaging music, with thrilling rhythmic drive, and more likely to appeal to those more familiar with jazz and rock than, say, a Mozart or Brahms concerto. Wang & co. relish the modernity of the music, while also fully keeping it contained within its neoclassical framework - a style of 20th century music which had composers like Stravinsky integrating formal and aesthetic aspects of the Classical era (ie. Haydn and Mozart) while also writing in a decidely post-expressionistic, modern idiom. In other words, this is music that sounds familiar in some ways, but “new” in others. Seasoned classical listeners will hear echoes of Hindemith and Poulenc most of all.

One of the “new” things in Shostakovich’s First Piano Concerto is the fact that there is a substantial solo part for trumpet, not something you would encounter in any late Romantic concerto, but a tipping of the hat to the multi-instrument concertos of the Baroque and Classical eras, which adds a lovely spice and frisson to the proceedings. The recording nicely brings out the trumpet while keeping it integrated within the orchestral canvas.

Principal Trumpet of the BSO and Soloist in the 1st Piano Concerto, Thomas Rolfs

Principal Trumpet of the BSO and Soloist in the 1st Piano Concerto, Thomas Rolfs

The work actually started out as a trumpet concerto, but once Shostakovich decided to include piano as well, that instrument quickly became the prominent one. The blend of piano, trumpet and a purely string orchestra represents a piquant (and very typically neoclassical) blend of sonorities.

The composer was, like Rachmaninov and Prokofiev, a formidable pianist.

Dmitri Shostakovich (from collection of Laurel Fay)

Dmitri Shostakovich (from collection of Laurel Fay)

In his student years he made money on the side by accompanying silent films, which is probably where he acquired the knack for quoting other pieces of music seamlessly in his scores, nowhere more so than in this concerto, which quotes Haydn and Beethoven (“Rage over a Lost Penny”), and liberally evokes jazz and the music hall. When the solo trumpet plays the melody to a popular Viennese song from 1800, “Ach, du lieber Augustin” - an hommage to a popular balladeer and bagpiper of the times who entertained with his dark sense of humor - it offended the prudish Soviet musical establishment.

Shostakovich at this time (1933) was happy to offend, cheekily mocking the overt seriousness of the grand Romantic piano concertos of his forbears like Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov. He was really feeling his oats. His recent First Symphony had been a triumph, and he had just completed his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsenk, a strident, challenging psychological drama of nerve-grating intensity and searing emotion. He had yet to experience the severe official blowback that this opera would engender (resulting in his withdrawal of the opera and the just completed 4th Symphony), and the fear (for his life) and anxiety which would result in a radical about-turn in his compositional style that announced itself in the 5th Symphony (1938).

Yet beneath the glittering surface of the concerto is that vein of melancholy so characteristic of Shostakovich’s music, nowhere more so than in the poignant slow movement, fashioned as a waltz. Yes, there is always the ironic twinge, but beyond that something darker and more sober clings. Anyone who thinks Yuja Wang is all surface brilliance will have that notion dispelled here, as she brings out all the music’s variety of expressive modes, beautifully supported as she is by the sweet Boston strings.

The brief, bridging third movement leads us into the knockabout Finale, a veritable roustabout whose final pages are tossed off with a joie de vivre which will have you jumping out of your listening chair. (You will literally levitate at Wang’s note-cluster chord that erupts during the trumpet’s brief diversion into a more languid, albeit ironic, aside to the dominant helter-skelter progress of the movement). Throughout this performance the trumpet playing of BSO Principal Thomas Rolfs is a bright, strong, thrilling counterpart to Wang’s virtuosity. The final peroration, trumpet fanfaring over Wang’s repeated chords (with echoes of the end of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella), is like fireworks bursting across the sky. Man is this fun: music as fresh and vital as it must have sounded in 1933!

Wang, Nelsons and the BSO in full flight during the 1st Piano Concerto (Photo: Aram Boghosian)

Wang, Nelsons and the BSO in full flight during the 1st Piano Concerto (Photo: Aram Boghosian)

Twenty years passed before Shostakovich returned to the piano concerto form, and those intervening years saw him live through the unspeakable horrors of the Stalin purges, the disappearance of numerous friends and colleagues, and his own personal struggle to somehow survive both physically and emotionally, let alone as a creative artist trying not to compromise his ideals or personal truth while facing constant official scrutiny. His music underwent radical aesthetic shifts to avoid censure, and himself being carted off to the Gulag.

With the death of Stalin in 1953, the thaw in the cultural climate led Shostakovich to pen probably his greatest symphony, the 10th, complete with its unvarnished portrait of the finally deceased dictator - red in tooth and claw in the second movement. Other major works like the First Violin Concerto and Sixth String Quartet were recently completed, the 11th Symphony underway, when the composer composed the Second Piano Concerto as a 19th birthday present for his son Maxim, who gave its first performance in May 1957. (Maxim would go on to a fine career as a conductor; his EMI/Melodiya rendering of his father’s final symphony, No. 15, remains unequalled in the catalogue and, unusually for recordings of this provenance, is a certifiable audiophile gem that should be in every collection of the Shostakovich enthusiast).

Father and Son: Dmitri and Maxim Shostakovich

Father and Son: Dmitri and Maxim Shostakovich

Acknowledging that his son, no mean pianist, was nevertheless not on his father’s level, the solo part is less demanding and obviously virtuosic, with many of the barnstorming passages written in octaves. The work represents a “break’ from the intensity of those other contemporaneous works, and is charming in the way you’d expect a present from father to son to be. Shostakovich’s writing for full orchestra here brings a lithe piquancy to the wind and brass textures.

After a hushed introduction the slow movement brings forth one of the composer’s most beautiful and engaging melodies, colored by unexpected, gorgeous harmonies - lending a heart-stopping quality that would not be out of place in a Hollywood movie of yesteryear. (Remember that Shostakovich wrote many exceptionally fine film scores, not least for a famous Soviet Hamlet in 1964 by director Grigori Kozintsev). Shostakovich channels Rachmaninov and Prokofiev here, and fully equals them, without ever veering into bombast. As critic Robert Layton commented: “the composer was able to operate at a level of self-mockery and serious poetic comment at one and the same time.”

The Finale is another of Shostakovich’s effervescent helter-skelter dashes, full of youthful high spirits and unabashed joy. Wang tears through this with gay abandon, matched at every turn by conductor Andris Nelsons and his Boston players. You will gasp at the power and precision of Wang’s repeated notes in the final bars.

If that weren’t enough, DG offers some filler gems in the form of extracts from Shostakovich’s Bachian cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, op. 87 (plus one scintillating Prelude from his earlier op.34) - one of the great 20th century masterpieces of the solo piano repertoire. Wang is (again) almost casually brilliant here, and I can only fervently hope and expect she will release a complete recording of this essential cycle. This is all music ideally suited to her musical temperament. (Until then I direct readers to Shostakovich’s own recordings of these on the Classical Russian Revelation label - there are several discs of the composer's own recordings of his piano music - along with Vladimir Ashkenazy’s complete 1999 cycle on Decca, one of the glories of his catalogue).

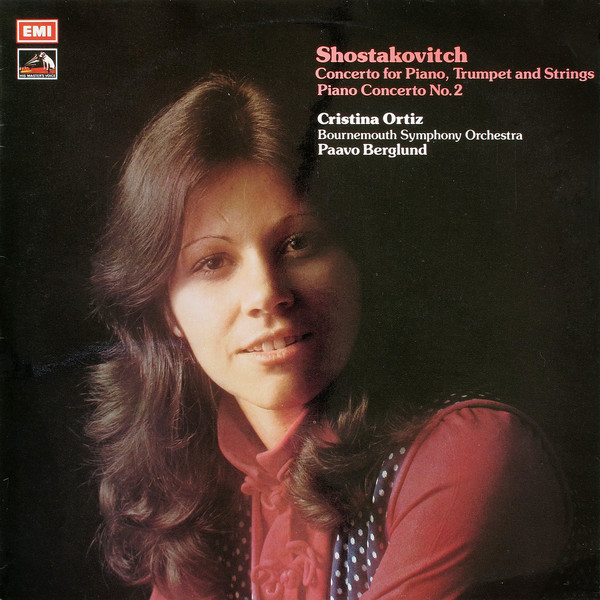

Hitherto, my usual vinyl go-to for the Shostakovich piano concertos has been - since I bought it when it was first released in 1975 - Brazilian pianist Cristina Ortiz’s luminous, incisive rendering in vintage EMI sound with Paavo Berglund and the Bournemouth Symphony. (All the Berglund/EMI records are serious classical collector essentials, in my view).

But listening to this excellent record next to Yuja Wang only serves to illuminate just how meteoric and unique a performer Ms. Wang truly is. She and the Bostonians (and the engineering team) just take everything to the next level.

No, I will not be jettisoning Ortiz, nor my copy of Shostakovich himself playing these works, nor a few other CD favorites (Leif Ove Andsnes, Lise de la Salle, and Martha Argerich in the First Concerto). But after listening several times to the immaculate pressing of this Yuja Wang firecracker, I can only echo the words of Jed Distler reviewing this set in The Gramophone: “Yuja Wang’s performances are of a wholly individual character and brilliance that discourages comparison.”

And yes - this is indeed a new audiophile classic (at least in its vinyl incarnation).

One of Yuja Wang's justly celebrated encores... (Amidst the flurry of notes listen to how the musical line is crystal clear - this has to be heard to be believed!):

.png)