Sonny Rollins "A Night At The Village Vanguard"— First Time Release Cut From the Original Master Tapes

Tone Poet 3 LP Set Is One Of The Great Jazz Reissues

In October 1957, Sonny Rollins was booked for a two month gig at New York City jazz club, The Village Vanguard. Though widely regarded as the most innovative and important saxophonist in jazz, Rollins was, in his own words, "so disillusioned with myself that I was afraid to hear myself." At the Vanguard, he was leading his own band for the first time and searching for a way to play jazz that was freer and more expressive than the bebop style of harmonic improvisation created by his idol Charlie Parker. Rollins had already developed and demonstrated mastery of his own post-Parker style on Saxophone Colossus and on a series of albums for Prestige and Blue Note but still he was dissatisfied.

Something was missing. When asked about his vision of music for the Vanguard gig, he said, "I don't remember exactly what it was…to be able to state it. The closest I could come is to refer back to MY idols, you know, all the guys that I liked. One guy was Ike Quebec."

That Rollins would credit Quebec, a pre-bop tenor saxophonist in the Coleman Hawkins-Ben Webster tradition, whose recording career began in 1940 as his inspiration, seems at first odd and surprising. He was not, unlike Rollins, a super technically adept player or a master of sophisticated harmony, and no one ever said that Quebec was an innovator. He was, however, a great melodic improviser and a very emotional player. Ike Quebec wasn't concerned with notes and chords but got himself out of the way and let the music come through him. What Rollins was trying to express at the Vanguard was a new attitude about music, that it should be about playing emotion freely, in the moment and not about intellectual concepts and technical perfection.

"Getting the musical vibe right" at the Vanguard was not easy. Rollins was looking for something special that he could hear. It was wild, loose, passionate, funky music that was also adventurous, technically advanced, and new. He went through a lot of musicians searching for the sound before settling on a quintet with Donald Byrd (trumpet), Gil Coggins (piano), Jamil Nasser (bass), and Roy Haynes (drums), who were all experienced, highly respected New York jazz pros. Alfred Lion, co-owner of Blue Note, liked what he was hearing and arranged for Rollins to record live at the club on November 3.

But Rollins still wasn't hearing on the bandstand the something special that was in his mind and, shortly before the recording date, fired the band. The sensible course at this point would have been to hire some other top flight jazz pros and record a safe, conventional bop album. It was New York in 1957. A few phone calls and Wynton Kelly, Lee Morgan, Paul Chambers, and Art Blakey would have been at The Vanguard and playing their butts off.

Rollins didn't want "safe" and another great hard bop album. He'd already made a lot of great hard bop albums. He wanted to experiment, put himself in a new situation, and see if he and his band could conjure up that special feeling he was searching for. Upon the recommendation of Max Roach, he hired a nineteen year old drummer, Pete LaRoca, who had played almost exclusively in Latin bands and had never recorded. The bass player---Donald Bailey--- a little known Baltimore musician who also had never recorded, was an even more unexpected choice.

Rollins' most radical decision was not to use a piano or another horn and make the group a sax, bass, drums trio, a very unusual lineup for 1957. Rollins had recorded the audiophile classic Way Out West with only bass and drums earlier in the year and was the first to use the format consistently. In Rollins' words, "a piano led me in a certain direction which was not what I wanted…A piano inhibited my freedom."

November 3 was a Sunday, so the Vanguard had a matinee in the afternoon and two sets at night. Rudy Van Gelder, Alfred Lion, co-partner in Blue Note, and company photographer Francis Wolff were all in the club among what was apparently a sparse crowd when Sonny took the stage to play the matinee with the all but unknown bassist and drummer. Blue Note was known as a hip, artist friendly company, but Lion and Wolff had to have had some doubts and worries about Rollins' band.

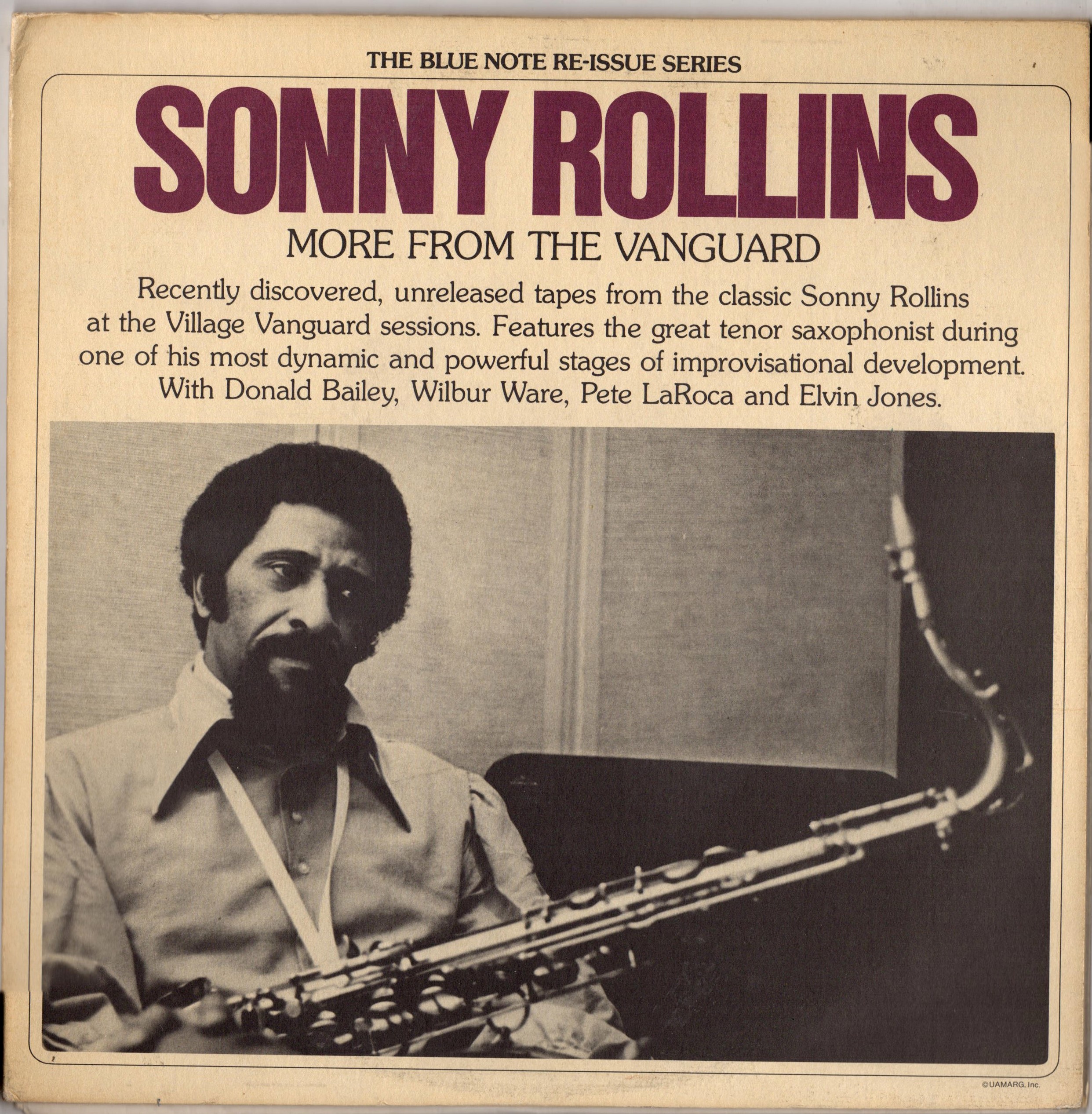

Sonny's plan for recording at the Vanguard was to be as spontaneous as possible. He hadn't rehearsed with Bailey and LaRoca, and the tunes he called, all well known standards, had no agreed upon arrangements for solos or endings. Sonny set the tempo, and off they went to where nobody knew. They played five tunes in what was probably a forty five minute set. One of them was released on A Night At The Village Vanguard Blue Note 1581 in 1958, and another on More From The Vanguard in 1975. The other three tunes were rejected for release and are apparently lost.

After the set, there was a four to five hour break before the evening shows. At some point during this period, it was determined that bassist Wilbur Ware and drummer Elvin Jones would replace Bailey and LaRoca. We now enter the realm of mystery and speculation. Rollins has said, "I was trying to get them for the entire session but they did not arrive until after the matinee had ended." Elvin Jones claimed that he was out drinking in Greenwich Village and happened upon Wilbur Ware outside the Vanguard, who told him that Sonny was looking for him. Ware's version, which is contradicted by the Blue Note session log, was that he and Jones sat in during the first set and played the rest of the night. The likeliest explanation is that Rollins, dissatisfied with Bailey and LaRoca, and probably, at the urging of Lion and Wolff, made emergency calls to Ware and Jones, asking them to get down to the Vanguard. However, it came about; they played the two evening sets, and fifteen tunes were recorded and all except one were released.

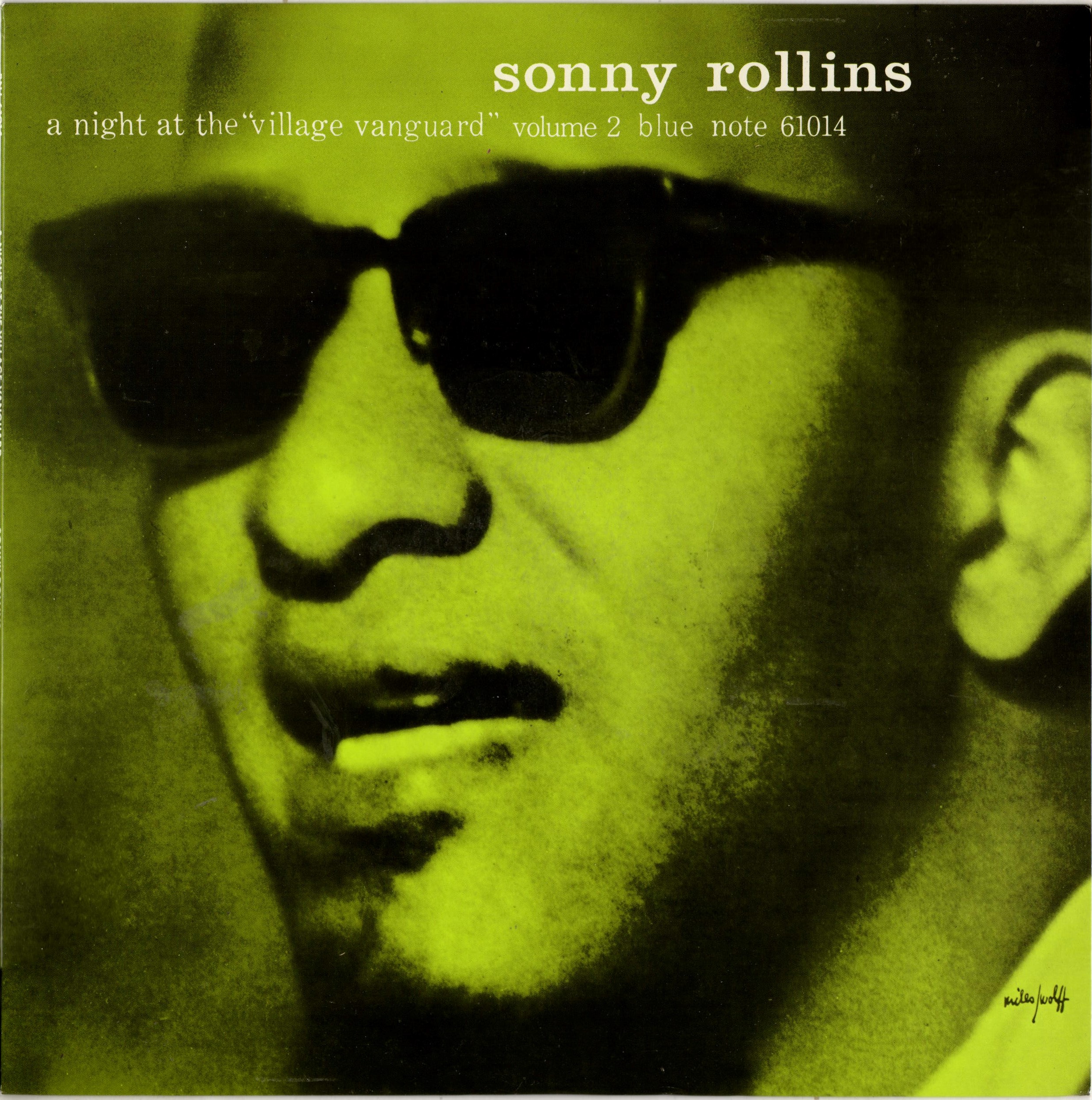

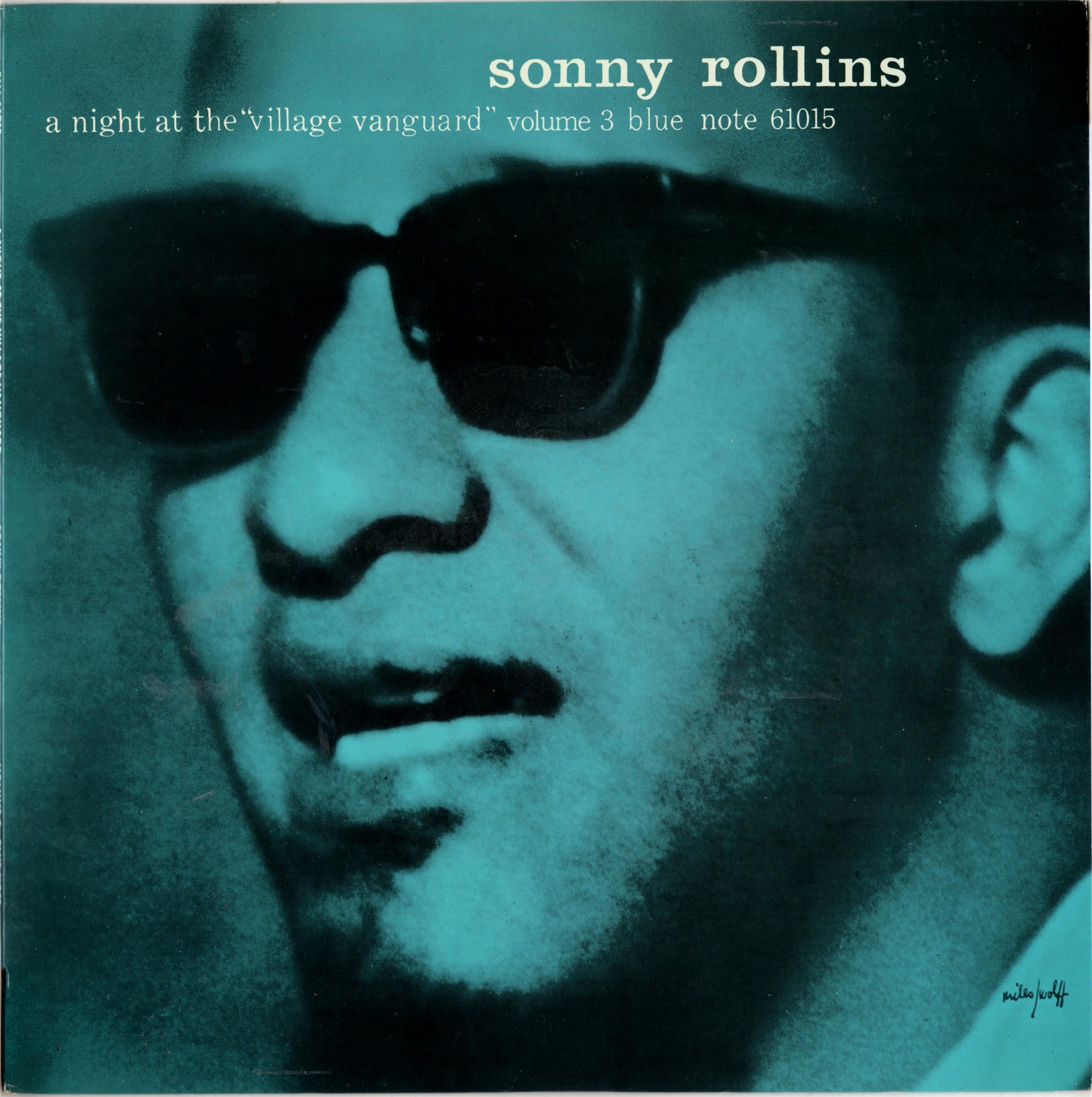

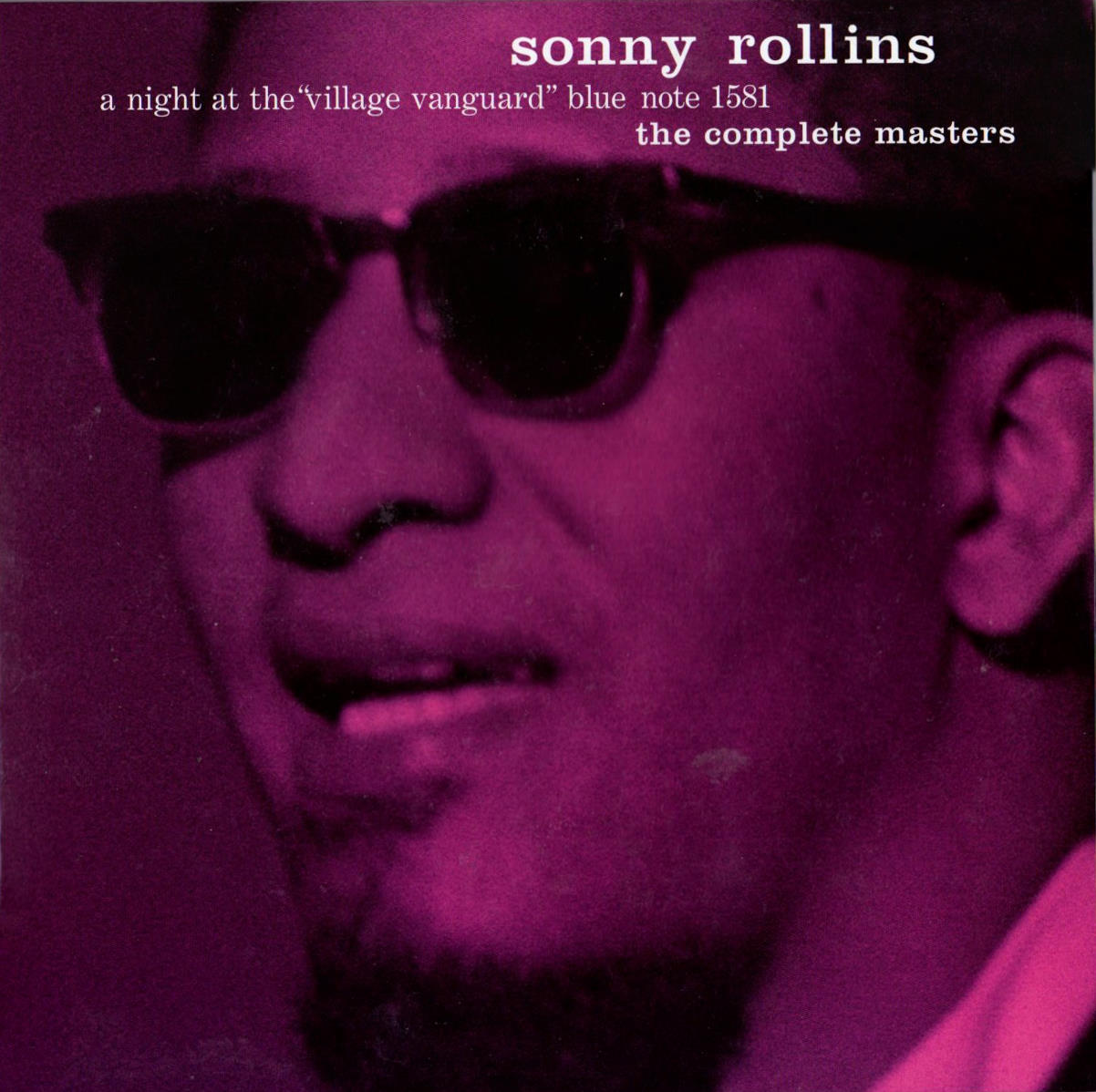

A Night At The Village Vanguard: The Complete Masters does not play the songs in the order they were recorded, as does the 1999 RVG edition 2 CD set. The first LP is the same tunes in the same order as Blue Note 1581. The second and third albums are the tunes first issued in 1975 on the 2 LP set More From The Vanguard, but Tone Poet has elected not to follow the same track listing but has instead put them in the order they were on A Night At The Village Vanguard Volume 2 and Volume 3, the Japanese Toshiba issues of the same material.

The first LP of The Complete Masters begins by giving us something not issued on Blue Note 1581, and we hear Rollins introducing "Old Devil Moon" and confessing that he is not sure which Broadway show the song is from. Audience members chime in correctly that it was from Finian's Rainbow, but Rollins jokingly announces the tune as from Little Abner. He counts off a Latin feel, which Elvin Jones abandons after the first chorus. Elvin was not yet the technically masterful drummer he became with Coltrane but the basis of his style—interactive, polyrhythms over a mostly unstated pulse—was in place. Rollins is clearly inspired by the constantly varying rhythmic backdrop Elvin provides and plays a hard swinging solo, digging in hard against some aggressive drum rolls.

"Softly As In A Morning Sunrise," usually played as a slow ballad, is played mid tempo over great walking bass by Wilbur Ware. Elvin's playing is a bit aggressive for a ballad, but Sonny goes with him and blows some beautiful lines that play with the time.

"Striver's Row" has the same chord changes as Charlie Parker's tune "Confirmation." Sonny doesn't play Parker's melody but launches into a solo of furious creativity that shows his complete mastery of bebop while playing freer and not confining himself to the chords. Ware and Elvin just set down a steady groove and let Sonny play. His rhythmic intensity is amazing. It's one of the great jazz solos.

"Sonneymoon For Two" is a Rollins blues original, and his first wailing note lets us know that this is a blues. His solo has some very vocal bluesy phrases, some astonishing sax master runs that swing incredibly hard, some very hip dissonant phrases, and by the end, he is just wailing over a wired up Elvin throwing everything in his bag at Sonny. The fours between Elvin and Sonny are simply wild.

"A Night In Tunisia" is from the matinee with Bailey and LaRoca, who both sound tight and nervous. LaRoca's playing is busy, and he sticks with the same basic rhythm fill for nearly the whole tune. It doesn't seem to bother Sonny, who plays the melody with ferocity and then a wailing, grooving, aggressive solo that wanders away from the theme while playing with the rhythm.

"I Can't Get Started," one of the most played jazz ballads, starts with Sonny softening his tone so that we hear his roots in Lester Young. After the melody, they go into a modern ballad double time feel, and Sonny plays a wonderful solo that is not pretty but lyrical; not a beautiful version of the tune but a beautiful expression of Sonny's feelings about the tune. In the end, he throws in a quote, "I've Grown Accustomed To Her Face," which, unlike many jazz quotes, is wonderfully appropriate. It's one of the great jazz ballad performances.

The second LP begins with another version of "A Night In Tunisia," this one from the evening. Elvin, unlike LaRoca at the matinee, plays the rhythm Dizzy Gillespie used when playing the tune. Rollins plays an incredible solo that is really a duet with Elvin's polyrhythmic, nearly out of control, playing which ends at an intense peak. After a drum solo, Sonny plays the theme, improvising on it and swinging hard, but he doesn't play the verse, and Ware and Jones apparently don't know whether he's playing another solo or the out chorus. They end raggedly, which undoubtedly kept this exciting performance off BN 1581.

With "I've Got You Under My Skin," we're back at the matinee. Bailey's bass is busy and hesitant, as if he's trying to find the groove under Rollins' loose feel. LaRoca seems like he doesn't know where the time is either, and he and Bailey don't hook up until near the end of the chorus. Sonny is unperturbed and just goes for it, playing a solo full of rhythmic genius as he plays with the time and various motives while improvising on the melody. Sonny and LaRoca trade fours, and then there is a bass solo, which is certainly unusual. Bailey doesn't really solo but just repeats the part he has been playing as accompaniment. Was the solo a mistake or a misunderstanding? Things get even stranger. Rollins comes back improvising brilliantly on the melody and signals by his phrasing that he is ending, but the bass continues playing the last four bars repetitively. Rollins plays along and improvises over the four bars for nearly two minutes. Was this an example of brilliant on the spot arranging or a brilliant improvisational response to a mistake?

Next up is the alternate version of "Softly As In A Morning Sunrise." This version is a little faster than the one on BN 1581. Sonny plays the melody using his softer, rounder sound and accenting some of the notes very personally. Inexplicably, Sonny drops out. Did he intentionally mess up the take because he was dissatisfied with the rhythm feel or possibly the way he played the melody? Ware plays alone until he gets back to the top of the tune, and then Rollins plays a beautiful, relaxed melodic solo with some Lester Young phrases. When he finishes, Ware plays another longer, bass solo, which displays his big sound and strong swing. It's an excellent, beautiful, melancholic performance except for the strange beginning and two bass solos. Rollins obviously thought so too and wanted the tune on the album, so he called it again in the next set.

"What Is This Thing Called Love," another ballad, starts with an odd, abstract drum intro, and then they jump into a fast medium tempo. Rollins, clearly at this point in his career, disliked playing ballads at the usual slow tempo. Over Elvin's increasingly wild polyrhythms and some very odd fills, Rollins swings hard, repeating some motives with different rhythmic accents in one of his "inside but out" solos which do not adhere to the chord pattern and ignore bar lines, but stay within the scale and key.

The third LP begins with "All The Things You Are," another ballad, and once again, it's played mid-tempo. After playing an abstract version of the melody, Sonny plays a solo that manages to be quite far out for 1957 while at the same time playing enough echoes of the melody so that you always know where he is. Wilbur Ware's bass solo is a masterful melodic improvisation.

"Woody 'n You" features another Rollins passionate, spontaneous outpouring of wild, rhythmic, melodic improvisation that swings so hard and with such momentum that Elvin nearly abandons the time and responds with constant elliptical, nonlinear, riffing, rhythmic commentary on Rollins' solo. Jones' playing here is nearly free jazz but Ware's grooving bass holds it together. The performance is a masterpiece that presaged much of sixties jazz and remains challenging today.

"Four" features more adventurous "inside but out" harmonically free playing by Sonny that wanders away from the chords as he improvises on short motives unrelated to the song, even throwing in a "Shortnin' Bread" quote while, as always, he plays with the rhythm and the time. Elvin is a little more restrained here, and he and Ware lock in together and swing hard.

"I'll Remember April" begins with Sonny demonstrating to Elvin the rhythm he wants him to play, a "Caribbean" "island" feel, unusual for the tune, which is usually played as a slow ballad. After the melody, Elvin is back to his usual hard, swing with polyrhythms and teetering on the edge of losing the time while Ware provides the groove. Sonny's solo here, as on all the other ballads played at the Vanguard that day, breaks completely with jazz ballad tradition. He plays "April" almost up tempo with the same hard, blunt tone he uses for the swinging tunes, nearly ignoring the melody, not trying to sound pretty or romantic. He plays the tune the way he hears and feels it, unconcerned about the audience's expectations of how a ballad should be performed.

There are two versions of "Get Happy." On the long version, Sonny shows Elvin the rhythm he wants. Elvin plays his most straight ahead, hard swing of the night, but he and Sonny don't seem in sync. Sonny plays a brilliant chromatic solo on the scale but without his usual rhythmic freedom. After Elvin's drum solo, the tempo seems noticeably sped up, and Sonny plays the out chorus perfunctorily as if he knows this take was not going to be used.

The "Get Happy Short Version" is the second try and the rhythm is slower, swings more and feels better. Sonny's solo uses an approach similar to the "Long Version" but with much more rhythmic freedom, at one point falling way behind the beat. The way he finishes the melody is eccentric, humorous, and like nothing anyone else would play.

A Night At The Village Vanguard: The Complete Masters documents some of the greatest playing by Sonny Rollins, who some, including me, would say is the greatest of all jazz improvisers. It is a masterpiece but a singular and eccentric one, replete with mistakes, or if not mistakes, "misunderstandings." The tunes were warhorses, even in 1957, and are played jam session ragged without rehearsal or planning. The music isn't slick and verges on "train wreck" sometimes. It's wild, creative, emotional expression. A human music that exalts in the moment, the joy of life, NOW, the joy of not knowing what will happen next. Sonny Rollins played NOW like few ever have at the Vanguard, and it's a sublime, wondrous experience to listen and marvel at his incredible, unflagging creativity, to listen to the music just flow through him. To listen to him play jazz.

A Night At The Village Vanguard: The Complete Masters was mastered from the 7.5 ips tapes Rudy Van Gelder recorded at the Vanguard. All previous issues of the music were made from a copy tape he made at 15 ips.

For my comparative listening, I played my original Blue Note 1581, my 1975, More From The Vanguard, and my Toshiba Volumes 2 and Volume 3, then I listened to The Complete Masters. At the beginning of Side 1, I was immediately surprised by the warm, natural sound of Sonny's voice, the clarity and separation of the audience's voices, and the Vanguard room sound during his intro to "Old Devil Moon" and thought, "This is going to be better." Then the music started, and I was stunned. The sound wasn't just better. It was revelatory. The treble was more smooth and extended, the bass deeper and more defined. There was far more low level detail and room sound. Sonny's horn was very dynamic and 3D. All the rhythmic nuances of his style seemed more pronounced because of the improved dynamics. The unique dark, blunt "Sonny sound" was thicker and hotter. The music was more real, more live than I had ever heard it before.

Just to be sure, I did immediate back to back comparisons. My clean, original BN 1581 sounded notably constricted compared to Complete Masters. Treble and bass were less extended. Soundstage was narrower and less deep. Dynamics were much less wide. Elvin's cymbals sounded much less sweet and a bit clanky. Overall, the tonal balance of 1581 was much harsher. These differences were not subtle or of the type that would be audible only on very high end systems.

More From The Vanguard had a much harder, more "in your face" sound. The tonal extremes were overly emphasized, especially the bass, which seemed "thumpy.” There was much less low level detail, and after Complete Masters, I found it unpleasant to listen to.

Toshiba's A Night At The Vanguard Volumes 2 and 3 LPs sounded very similar to More From The Vanguard but with slightly more bass and reverb added. The reverb was extremely annoying, and the LPs were near unlistenable after hearing the clean, real sound of The Complete Masters.

The Complete Masters comes in a gorgeous triple sleeve, which reproduces the original back cover of BN 1581. Inside are some heretofore unseen pictures of Sonny at the Vanguard and reproductions of the front covers of the Toshiba LPs. Included is a booklet with more beautiful photos, and essays by Bob Blumenthal and Nate Chinen, a relevant excerpt from the Saxophone Colossus bio and a wonderful interview of Sonny by Don Was.

My three LPs, pressed at RTI, were glossy, lustrous, without any marks, and flat. They all played superbly and quietly.

A Night At The Village Vanguard: The Complete Masters is a masterpiece reissue of a musical masterpiece. It is one of the very greatest jazz reissues and is an essential purchase for anyone with a more than a casual interest in jazz.

Copyright 2024 and all right reserved by Joseph W. Washek

.png)