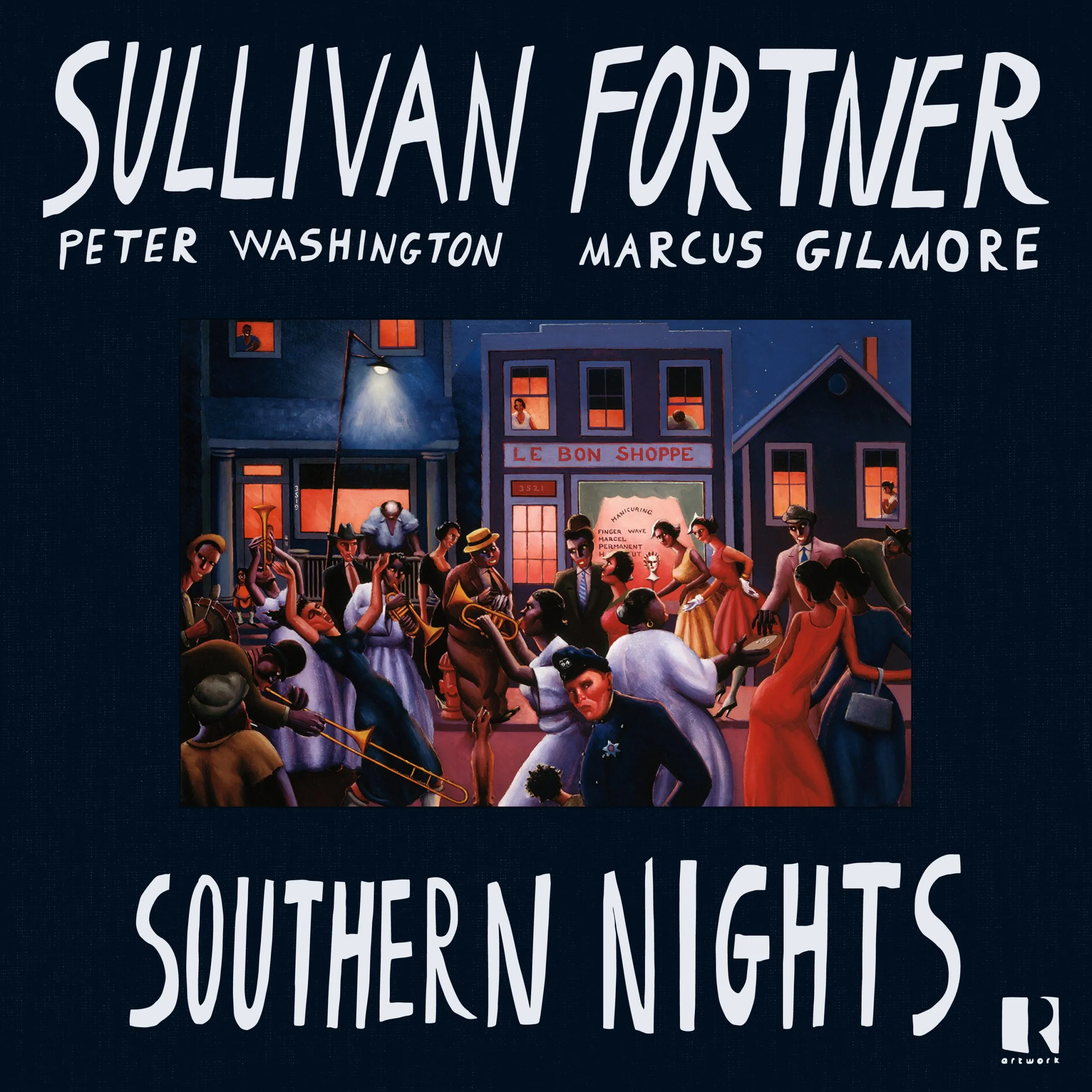

Sullivan Fortner's Southern-Night Delights

The virtuosic pianist's merrily deep pleasures

Several years ago, I described Sullivan Fortner’s piano style as “Erroll Garner channeled through Chico Marx.” Since then, his range has widened, his virtuosity deepened, his wit sharpened.

On the opening (and title) track of his new trio album, Southern Nights, he begins with breezy strums of the strings inside the piano, follows with some syncopated sparkles on the keyboard, then angles into the song (written by his fellow New Orleansian Allen Toussaint) with a spirit that invokes not just Garner’s grace and Chico’s playfulness but also the soulful hip of Dr. John. On the subsequent eight tracks (most of them standards, ranging from Cole Porter’s “I Love You” to Clifford Brown’s “Daahoud”), he whips up concoctions of Monk, Bud Powell, McCoy Tyner, and various unabashedly pop influences. (Check out his head-spinning cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Don’t You Worry About a Thing” on his previous album, Solo Game.)

At age 39, Fortner has emerged as among the handful of most versatile, inventive, and pleasurable—simply put, one of the best—jazz pianists on the scene.

Southern Nights, on the Artwork label, was recorded in July 2023 near the end of a six-night gig at the Village Vanguard with a top-flight band—bassist Peter Washington and drummer Marcus Gilmore—that had never played all together before. (Washington and Gilmore hadn’t met before, though Fortner had played with each of them separately.) I saw the trio play in the middle of that week; they were still ironing out a few rough spots, but for the most part they dazzled. I don’t think they’ve played together since (they’re each in heavy demand), but they should.

Especially on that title tune, Washington (nearly 20 years Fortner’s senior, best known for his work of nearly three decades with Bill Charlap’s piano trio) flits from time-keeping to pedal-point pivots to countermelodies to chordal anchors, all with high-spirit precision. Gilmore (Roy Haynes’ grandson and a master drummer in his own right, a contemporary of Fortner’s who has played with nearly every jazz star of the past decade) accents, shifts, and klook-a-mops around the beat with daredevil exuberance.

This is a superbly produced album, in that the best tracks are up front (the dancing-in-your-head interplay on the title tune may be the coolest piano-trio track of the past few years), while the final few—though still very good—don’t mesh with quite the same seamless excitement.

The tracks were laid down in one day at Sear Sounds, where Sullivan has recorded several times now, as a leader and a sideman, notably with his most frequent collaborator, the great singer Cécile McLorin Salvant. Todd Whitelock was at the controls (as he has been in many of those earlier sessions). Whitelock tells me that the piano was picked up by Sennheiser MKH 800 Twin microphones, the bass by a Neumann U67 and a Coles 4038 ribbon, and the drums by a variety of mics, though, as he put it in an email, “the magic was captured in the stereo overhead pickup using two vintage Neumann KM54s.” They were powered by Sear’s custom-modified Avalon analog console, fed into a ProTools HDX system at 96 kHz / 32 bits. He did the mixing at his own studio, using a Lynx Aurora for digital-to-analog conversion through a Sony DMX R100 console. Final printing went through a Dangerous Music Convert AD+ back to a ProTools Ultimate system. He mastered the disc as well, with a Magix Sequoia 17 Pro software program.

All this impressive audiophilia would be for nothing if the album sounded like a muddle, but the album—CD and streaming only (no vinyl, alas)—sounds terrific. Every aspect of the piano shines through—the bright percussive keys, the overtones’ bloom, the chamber’s resonance. The bass is plucky and woody. The drumkit snaps, booms, and shimmers.

.png)