The Agony and the Ecstasy: Transcendental Late Liszt from Leif Ove Andsnes

One of the least known, and most extraordinary, works of the late 19th Century receives a new Benchmark Recording

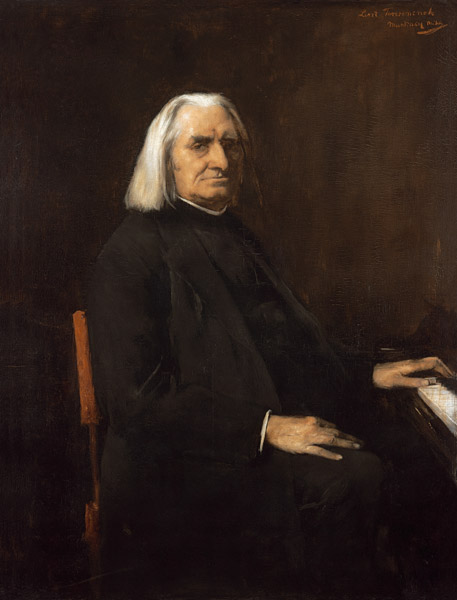

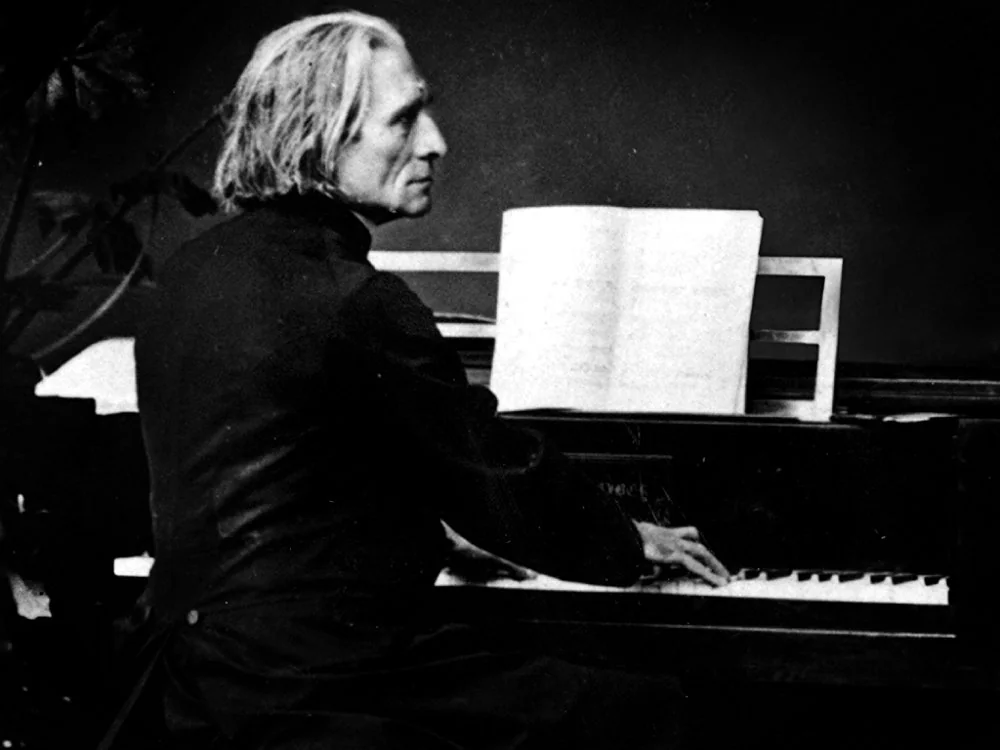

Franz (Abbé) Liszt in 1886 (Mihláy Munkácsy)

Franz (Abbé) Liszt in 1886 (Mihláy Munkácsy)

“For me, "Via Crucis" feels like an encounter with Liszt’s soul - a man grappling with the mysteries of faith, redemption, and human suffering. The work is remarkable for its avant-garde harmonic language and stripped down textures. Equally fascinating is the emotional impact; this is as much a prayer as it is music, embodying a timeless message of compassion and transcendence.”

Leif Ove Andsnes

It is rare indeed for me to discover a new piece of classical music (or any music for that matter) that so completely surprises and enthralls me, rivets me to my listening chair from first note to last, demanding 150% of my attention at every turn, and takes my mind and my heart to so completely a new realm that I feel like a different person after listening to it.

But this piece - and this remarkable CD - did all that, and more.

And the moment it was over, I knew I had to tell you all about it.

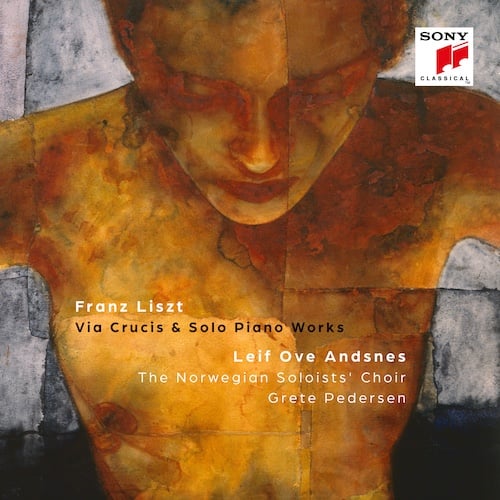

The main work on this CD - Franz Liszt’s Via Crucis (1879) - is rare stuff indeed, so rare that even though I knew of the work I had never actually heard it. So when this latest release by the great Norwegian pianist Leif Ove Andsnes was announced it was a no-brainer purchase (I have pretty much everything he’s ever recorded - yes, he’s that good).

Now most people, when they think of Franz Liszt, they think of the firebrand virtuoso pianist who toured Europe setting pianos and audiences on fire with his keyboard pyrotechnics, seducing half of Europe’s distaff gender in his wake.

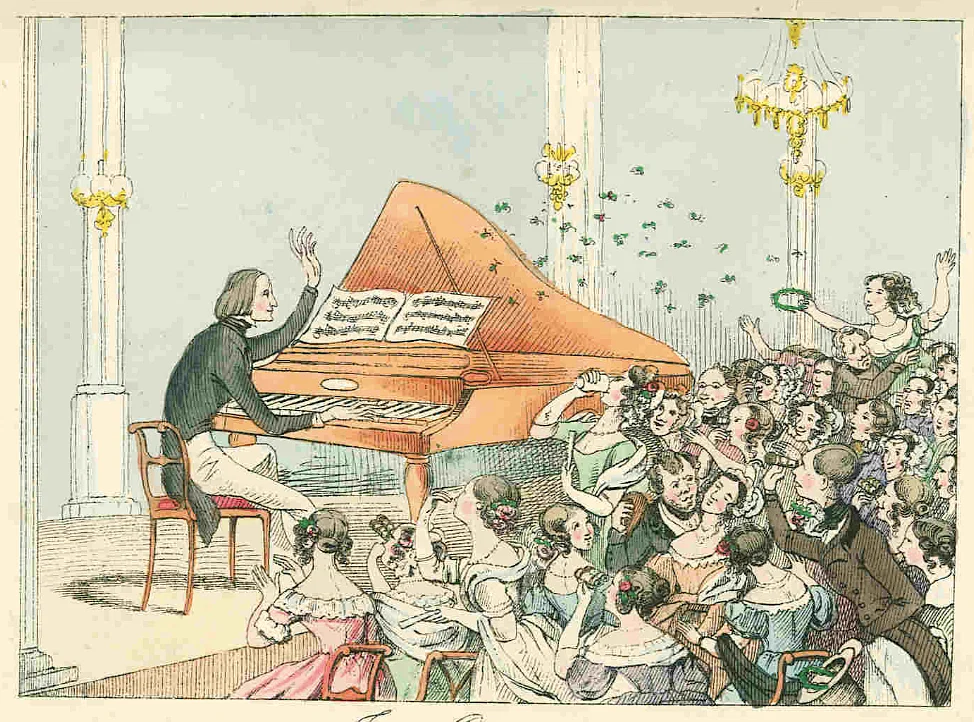

1842 Cartoon by Theodore Hosemann depicting the Height of "Lisztomania"

1842 Cartoon by Theodore Hosemann depicting the Height of "Lisztomania"

He was the original bad boy of music, the 19th century rock ’n roller - the equivalent of Mick Jagger, Robert Plant, Roger Daltrey all rolled into one. It was no accident that iconoclastic director Ken Russell opened his 70s biopic of Franz - titled Lisztomania (1975) - with the composer-pianist (played by Roger Daltrey in a nice piece of meta-casting) availing himself of a young married lady’s favors to the beat of a metronome.

I have my own little personal connection to old Franz via my wife’s Hungarian family on her mother’s side. He was a good friend of her great-great grandfather, Imre Széchényi (a talented musician himself), and occasional house guest throughout his life at the family estate at Horpacs, nestled deep in the countryside about four hours west of Budapest. The room in which he habitually stayed, in a prime location since it was situated next to the bathroom with newly installed running hot and cold water - a great luxury in those days - was referred to as “The Liszt Room”. This greatly puzzled my mother-in-law as a child, since Liszt in Hungarian means "flour", and she could not fathom why a room would, in effect, be called "The Flour Room"! Apparently, on one of his visits to Horpacs later in life, in 1872, Imre presented Liszt with his childhood piano which he had retrieved from the Liszt family home at Dorborján. In a surviving letter to Imre, the composer expressed his enormous gratitude. (The instrument remained at Horpacs until it was heavily damaged, like much of the house, by the Communists). On one occasion a persistent female stalker showed up outside the estate’s private chapel while Liszt and the family attended Mass. The custom was that anyone who wanted to attend Mass should be allowed entry, but informed of the lady’s arrival by a servant, Liszt used a casually dismissive gesture of his hand to indicate she should be sent on her way.

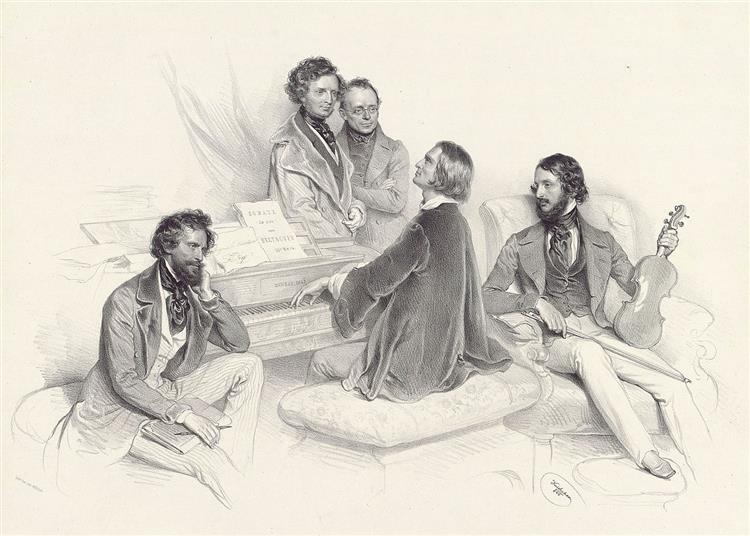

An Afternoon Salon chez Franz (Joseph Kriehuber 1846)

An Afternoon Salon chez Franz (Joseph Kriehuber 1846)

Liszt was the flame to which other moths of the creative community fluttered, counting major figures like Victor Hugo, George Sand, Hector Berlioz, Frederic Chopin, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Richard Wagner as his friends. In his own music, Liszt was at the vanguard of the Romantic movement, pushing the boundaries of harmony and form.

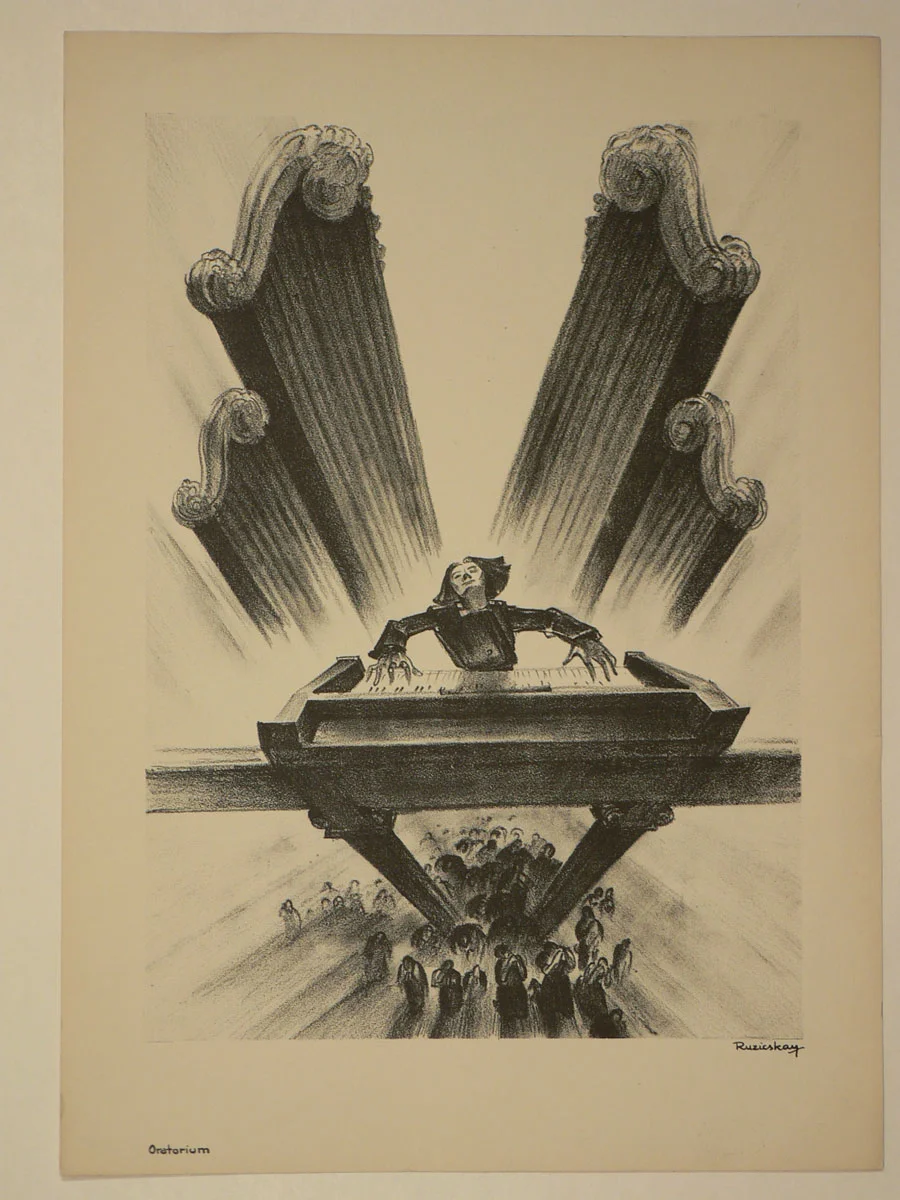

Oratorium - one of a series of 1937 prints by György Ruzicskay that convey the larger-than-life image that Liszt presented to the world

Oratorium - one of a series of 1937 prints by György Ruzicskay that convey the larger-than-life image that Liszt presented to the world

He moved the virtuoso piano sonata and keyboard cycles into not only the grandest of territory, but also anticipated impressionism; in his orchestral works he developed the so-called symphonic tone poem that would find its apogee in the grand statements of Also Sprach Zarathustra, Ein Heldenleben and the Alpine Symphony (to name but a few) by Richard Strauss. He pioneered the same thematic transformational procedures that Wagner codified in his operas, the so-called leitmotif technique. Liszt’s daughter Cosima, while still married to the leading conductor of the day, Hans von Bülow, began a torrid affair with Wagner, bore him two children while still married to her husband, and, after divorcing, eventually married dear old Dick, founding a musical dynasty at Bayreuth that would subsequently welcome Herr Hitler with open arms.

An interesting bunch of people.

But before the Romantic movement in classical music finally disappeared up its own derrière (so to speak) in an orgy of endless chromaticism and excess, the spiritual pater familias of the movement, good old Papa Franz, had something of a revelatory moment on his own personal Road to Damascus. Always a religious man, he found God anew, threw over earthly delights, and moved to Rome. Taking on Holy Orders (but not becoming a full-time priest) he became known as Abbé Liszt. During his later years he divided his time between Rome, Weimar (where he had directed the Court Orchestra for many years after winding down his touring activity), and Budapest, reconnecting with his Hungarian roots.

Liszt in 1858

Liszt in 1858

Likewise his music moved into a new realm that abjured virtuosity and empty flourish in favor of a more direct utterance, a mode in which rhythm and harmony were pared to the bone, in which simplicity held primacy.

There was a sense of going back in time, returning to the model of Bach, whose entire art was, to one extent or another, created as an act of homage to God: “Soli Deo Gloria” (“Glory to God Alone”) - the words Johann Sebastian would inscribe at the end of his manuscripts.

Except for one thing. Liszt retained that sense of harmonic adventure he’d had in his prodigal days, that pushing against the boundaries of tonality which was the preoccupation of the Romantic composers. But instead of disappearing into endless chromaticism, which would ultimately lose the thread, he simplified, making every unexpected note, every surprising chord count - like Bach. Yet unlike Bach he was not working within a strict tonal system with firm rules; with Liszt, just when you least expected it, a note, a chord, a phrase, a harmony would appear out of nowhere, like a shaft of sunlight, and it would astonish - or unsettle. Or both. It would not fundamentally disturb the edifice, but it would open a hitherto unnoticed window onto an unexpected view. Thus, while remaining within tonality, he also suggested a way forward beyond it.

His late works, rarely performed, rarely heard, sound as modern as anything this side of the 20th century. They are quite exquisite, one of the great treasure troves of 19th century music hiding in plain sight. Beyond their own worth, they anticipate Webern, Satie, even John Cage - and minimalism. There are moments in Via Crucis when you will swear you are listening to a piece by Arvo Pärt.

This new simplicity masking complexity was a perfect expression of Liszt’s newly acquired asceticism - and his embrace of religion. It was the musical equivalent - for the former prodigal - of a hairshirt.

And Via Crucis is maybe the most singular expression of this profound aesthetic about-turn.

Cast not for large orchestra, instead it is a piece that can be performed in a small church (as it is here), or even a large living-room. Existing in a number of versions, the one performed here is for chamber choir (including soloists) and solo piano.

Recording Via Crucis in the Ris Kirke, Oslo

Recording Via Crucis in the Ris Kirke, Oslo

In some ways it could just as well be an extension of, say, Brahms’s Liebeslieder-Walzer for piano duet and four-part voices (sometimes performed by soloists, sometimes a choir): the world of chamber music performed in the home feels very near. That intimacy is an integral part of the work’s appeal and power.

But in every other regard this is a BIG work, with big ideas and themes.

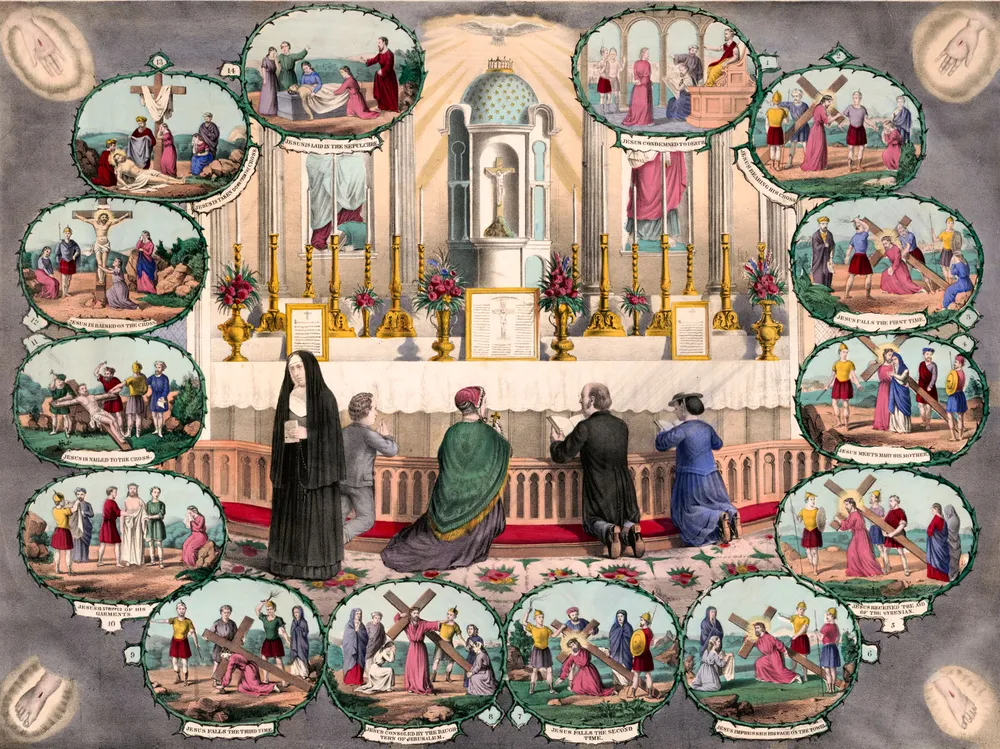

The Stations of the Cross - an explanatory lithograph from 1867

The Stations of the Cross - an explanatory lithograph from 1867

Its subject matter is the stations of the Cross: the progress made by Christ from his sentencing to death, through the stages of His crucifixion to the actual placing of His dead body within His tomb. The ritual of congregants passing by paintings of these Stations remains to this day a core event during Holy Week, the most important period of time in the Christian calendar. In other words, Via Crucis is a series of devout musical evocations of, and meditations upon, the heart of Christian mystery and faith: the suffering of Christ, His sacrifice and death (and His subsequent resurrection, implicitly rather than explicitly addressed in this work).

Now let me say right away that you do not need to be a practicing Christian or religious in any way to connect with this work, but its roots in the liturgy lend it a spirituality which even the most secular of listeners will resonate with (and I am definitely as secular as any, despite my deep roots in religious music, growing up as I did singing in serious church choirs in England). Listening to Via Crucis, I found myself thinking quite a bit about the music of Olivier Messiaen, and in particular the Quartet for the End of Time, which is likewise deeply rooted in Catholic faith, despite being a secular piece.

The ritualistic aspect of Via Crucis is established immediately in an introductory movement for piano and choir, with nods to monophonic plainchant and the Hymnal. We visit each Station of the Cross in the manner of Mussorgsky’s perambulations in Pictures at an Exhibition: with some of the vignettes depicted by piano alone, some by choir and piano, some by solo voices within the choir.

Even if you are not a student of Western music history, you will immediately be struck by a sense of this music being part of a long tradition, stretching back to monophonic Gregorian chant, the earliest multi-part sacred polyphony of Léonin and Pérotin sung in 12th century Notre Dame, and, of course, J.S. Bach. But the fact that the proceedings are led by that most secular (and, in Liszt’s time, modern) of instruments, the piano, removes the ecclesiastical veneer we are accustomed to in such works. This is a sound that all would have been familiar with, from the lowest to the highest classes, in settings ranging from beer taverns and school assemblies, to the drawing-rooms of stately homes and concert halls. The sonic familiarity of the instrument, its association with everyday secular life (and popular music), lends the music an accessibility, dare I say an almost proletarian equality, that mitigates against the more rarefied veils (choirs, organs, orchestras) that usually enshroud religious music. (The work was originally cast for organ and voices, but this version with piano is far more striking).

Jesus Meets His Mother (Edward Arthur Fellows Prynne, 1919 St. Stephen's House, Oxford University)

Jesus Meets His Mother (Edward Arthur Fellows Prynne, 1919 St. Stephen's House, Oxford University)

When, for example, in the Station titled “Jesus meets His Holy Mother”, the piano alone, unaccompanied by voices, expresses the extreme tenderness of the moment with a simplicity and an otherworldly harmonic palette that conveys both religious mystery but also carries echoes of a forgotten lullaby (the closest any art form gets to expressing the unique bond between mother and child). That sense of loving intimacy, and devastating loss, is expressed with a supreme economy of means - and it is all the more overwhelming for being done this way.

Almost imperceptibly the piano then moves into a musical depiction of Simon helping Christ carry the cross, with repeated chords conveying the relentless heavy tread of suffering without end. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, over a tonally ambivalent piano phrase, the Choir enters with the calming benediction of an unaccompanied Chorale, immediately calling Bach to mind.

Cut short as the piano and choir forcefully declaim “Jesus Falls for the Second Time”; but then distant women’s voices sing:

“The mourning mother was standing

Weeping beside the Cross

Where her Son was hanging…”

It’s a spellbinding moment.

The whole work thus unfolds as a tapestry of similarly carefully constructed effects and juxtapositions which seem to encompass so many of the formal and harmonic procedures of nearly ten centuries of Western music. But it’s all done so simply, directly, with such economy of means, that it makes the huge canvases of Wagner, Brahms, Bruckner, Richard Strauss and others seem like so much hot air and, frankly, vulgar in comparison. Emotionally the work constantly spins on a dime, keeps you guessing, while maintaining a steady forward progress, each Station of the Cross landing its considerabe punch. As the work proceeds, individual moments register with increasing intensity, and by the end you suddenly realize the cumulative effect is every bit as powerful as a vast oratorio or Requiem. Maybe even more so because of its economy of means.

We all know where the story is heading, but Liszt has one surprise up his sleeve.

Part of Barnett Newman's abstract take on the Stations of the Cross (1965/66)

Part of Barnett Newman's abstract take on the Stations of the Cross (1965/66)

For the final Station, “Jesus is placed in the Tomb”, gone is all the tension, and Liszt brings us into the same benedictory world that would emerge some years later in Fauré’s Requiem, the polar opposite of the operatic stürm und drang of Verdi’s setting. The choir sings a beautiful lyrical melody to the words:

“Hail Cross, sole hope,

Salvation and glory of the world

For the dutiful increase righteousness

Give pardon to evildoers.”

It feels like a balm placed upon an aching wound, a glimpse of paradise amidst darkness and despair. And when the final words are uttered, Liszt combines voices and piano in a manner that is almost halo-like (and some of you may experience, as I did, pre-echoes of Saint-Saens’ exquisite musical description of "The Aquarium" in the Carnival of the Animals - and it doesn’t feel weird at all, as if we were celebrating the sanctity of all creation). This is Liszt the master orchestrator at work, even when he is only using piano and voices.

“Amen. Hail Cross.”

All life and death, thought and deed, creation, the world, the universe is reduced to a simple unison utterance. This monophonic end, a call-back to the beginning of Western music in the simple manner of a concluding phrase of Gregorian chant, feels like it puts a cap on ten centuries of mutability and progression. But in Liszt’s design this is more than merely an end, as indeed his faith would dictate that the end of life is merely its own station on the way towards something else. There is an intimation that Liszt, knowing that his own composing journey is reaching its apotheosis, is presenting us with a door to an unknown future we can only guess at. Will we open it? Musically, Liszt is gesturing towards a possible way forward that grows out of distillation, simplification, and concentration of means, rather than the grandiose over-statement and over-abundance of his fellow late Romantics.

“In my end is my beginning”, as T.S. Eliot wrote.

Leif Ove Andsnes

Leif Ove Andsnes

On this CD, out of the silence emerges the strains of an apt selection of Liszt’s solo piano music: the Six Consolations from earlier in the composer’s career, and a couple of the mid-period Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses. Andsnes plays these as beautifully, yet as unmanneredly, as any; like Bach or Mozart, indeed. Those of you more familiar with the composer’s showpieces will be taken aback by the melodic simplicity and charm, the harmonic suppleness, the emotional reserve (yet also depth) of these short works.

It’s the perfect cap to a CD of quiet musical astonishment, one that will grant you a sense of aesthetic, spiritual and emotional repose - and renewal.

Ris Kirke, Oslo

Ris Kirke, Oslo

Recorded in a small Church in Oslo, Andsnes very wisely chose to use a 1917 Steinway belonging to the church itself, an instrument warmer and richer of timbre than its modern equivalents. (His album of Grieg recorded on that composer’s own piano is one of the gems of Andsnes’ catalogue, in part because of the unique sound of the instrument itself). With the Norwegian Soloists Choir and accompanying soloists demonstrating yet again the fine vocal and choral traditions of Scandinavia, all are captured in rich, full sound by engineer Arne Akselberg (Andsnes's regular collaborator) that conveys both grandeur and stringency when need be, plus intimacy all the time. There is a sense of being invited to participate in a very special occasion, one that demands concentration and close attention, but which will reward the listener with the discovery of beauty, purpose and truth in every phrase. You will find yourself leaning in to the music more deeply via the organic naturalness of the sound. But you can also just close your eyes and let yourself be lulled by the sheer beauty of music that is often conveyed in unfamiliar ways: drift away in a quasi-meditative state, from which you will emerge refreshed and cleansed.

At a certain point as I listened, this aural space felt so familiar that I suddenly realized I was having a sense memory of having sung and played in so many churches like this all over Europe when I was growing up. I could almost feel the mild draft wafting through the pews, and the slight chill in the air that old churches possess even on a Summer's day! (Throughout the 2000s and up to the present, Sony has consistently given its classical recordings some of the most organic digital sound out there). Conductor Grete Pedersen paces the proceedings to perfection, and all the performers combine to present the music with a sharply-honed sense of purpose, derived I feel in part by their wanting to share their discovery of this unknown masterpiece with the world.

Grete Pedersen

Grete Pedersen

I have no idea if this will ever be issued on vinyl. But whether you opt for CD, streaming or download, this should shoot to the top of your list of current classical essentials. (My rating of 9 for sound is given in anticipation that on vinyl or in Hi-Rez download form this might sound even better than it currently does). Excellent notes by Malcolm Hayes cap a release which I believe should rightfully sweep awards season.

This is music that will force you to slow down, and listen more attentively than maybe you have in a while. Once it begins it is impossible to turn away.

It compels, transforms - and offers a most welcome emotional and spiritual solace of a kind that is hard to find in today’s troubled world.

.png)