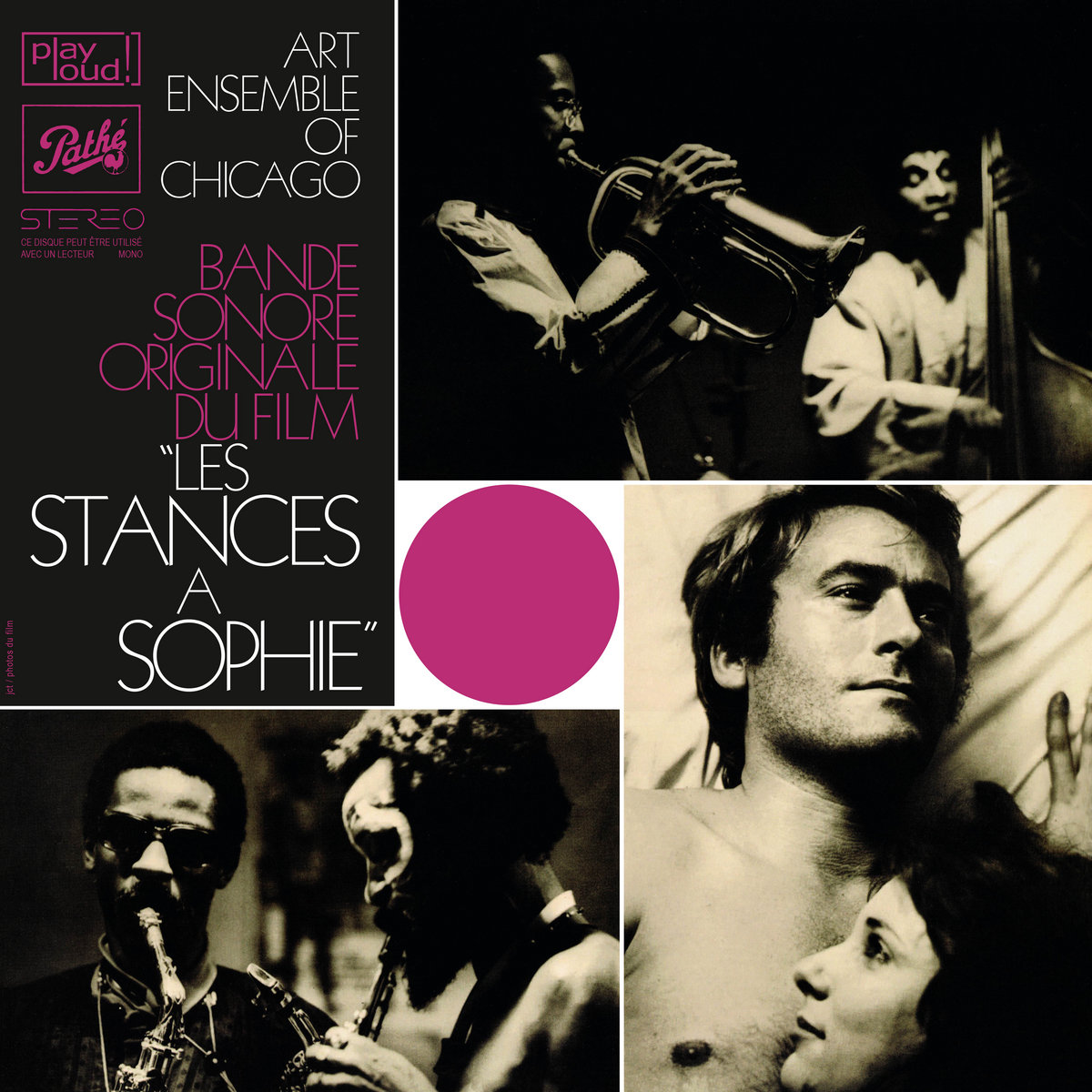

The Art Ensemble of Chicago's Avant-Funk Masterpiece

The long-vanished French soundtrack album is back, in vinyl only

“Funky” is not a word routinely linked to the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the pioneering avant-garde jazz group of the mid-1960s and beyond whose music tends more toward the cryptic and tangled. But put the needle on “Theme de Yoyo,” the first track of their 1970 album, Les Stances à Sophie, and you’ll be dancing in your head and on your feet in no time.

The album was produced as the soundtrack to a French film of that title, and “Theme de Yoyo”—which has vocals by the soul singer Fontella Bass, who at the time was married to the Art Ensemble’s trumpeter, Lester Bowie—is played during a scene at a disco. As Chris Morris, author of the informative liner notes to this new vinyl reissue, puts it, “It is almost certainly the only time in film history that anyone has attempted to dance to the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s music.” The effort posed no challenge.

Les Stances was recorded near the end of the group’s 13-month stay in Paris, where they laid down nearly as many albums. The film hadn’t yet been shot when the musicians stepped into the studio. They were given only the barest outline of the plot by the producers, who hoped to cash in on other recent French films with jazz soundtracks (Miles Davis on Louis Malle’s Ascenseur pour L’Echafaud, Thelonious Monk on Roger Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses). Alas, the movie, which I haven’t seen, bombed; the album—initially released on EMI’s Pathé Marconi imprint, then in the U.S. on Nessa—didn’t stay in the bins for very long either. A CD, released by Universal in 2007, is long out of print.

We are now lucky to have a vinyl LP, reissued by the Berlin label Play Loud! Productions (I first heard—in fact, first heard of—the album from a friend in Berlin while I was there this past spring), distributed in the U.S. by Forced Exposure.

Here’s the thing: This is a great album—and, by Art Ensemble standards, highly accessible. With one significant caveat (which I’ll get to in a bit), the sound quality is very good too.

The Art Ensemble was one of several jazz bands that burst onto the scene in the mid-to-late 1960s amid the flames (figurative and literal) of the civil rights movements, political assassinations, urban riots, and the Vietnam War. Many of the groups were concentrated in Chicago and formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). They included the members of the Art Ensemble—Lester Bowie, reedmen Joseph Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell, bassist Malachi Favors, and drummer Don Moye, who all occasionally switched to other instruments, toys, whistles, and bells—as well as Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Wadada Leo Smith, Henry Threadgill, and many more. A similar collective, the Black Artists Group (BAG), was formed around the same time in St. Louis by Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake, and Hamiet Bluiett, who later, with David Murray, created the World Saxophone Quartet. And there was the Jazz Loft movement in downtown New York City. (Many of them—including Mitchell, Braxton, Smith, Threadgill, Lake, and Murray—are still around and active.)

Their music was, and is, often called “free jazz,” though the label is a bit misleading. Most of them were deeply schooled in the fundamentals of jazz and classical music—harmony, theory, technique, sight-reading, composition, and so forth. But they also yearned to break out of old forms, to devise new musical languages to reflect the revolts and revolutions going on all around them. The Art Ensemble in particular dug deep into the tradition while also soaring through stratospheres of their own invention, embracing and eluding both. (The group’s slogan was “Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future.”)

The Art Ensemble was also very theatrical, Bowie often wearing a doctor’s white jacket, the others dressed in African costumes and ghostlike facial make-up. Their albums rarely captured the drama, tension, or wit—the playfulness and dead seriousness—of their live concerts. Perhaps because it was produced as a one-off film soundtrack, Les Stances à Sophie is an exception.

It begins, as noted, with a funk song—a head-rocking bassline and rolling drums, then Bowie blowing a crisp march melody, interjected by loud raucous saxophone eruptions, and then Fontella Bass singing hilariously angry lyrics by Noreen Beasley: “Your head is like a yoyo/ Your neck is like the string / Your body’s like a camembert / Oozing from its skin.” (Beasley later became a prominent animator at Walt Disney Studios.)

The seven tracks that follow include a noir-ish chase, a lovely ballad built on Monteverdi madrigals, and various jagged but upbeat improvisations. Only one track, “Theme Libre,” gets chaotic, and it’s the only one not used in the film. All of the pieces, except that one track (at least to my taste and apparently the film producers’) are riveting, galvanizing, and moving to boot.

Very little is known about the recording techniques. The original analog tapes are lost. Dietmar Post of Play Loud! told me in an email that Warner Bros. sent him a digital file with no explanation of its provenance, but it sounded pretty good, there were few adjustments to make.

For the most part, the album sounds very good. Bowie’s trumpet blares with golden clarity. When Jarman and Mitchell switch to flutes, the mix of steel and air is rapturous. The drums slam, the bass-plucks pop. I compared the Play Loud! reissue with an original pressing put out by the Chicago label Nessa in 1971. (I borrowed it from the critic, Gary Giddins, who happened to have bought it back then.) The differences are minor: the cymbals on the original are a little crisper, the ambience a little airier, but only a little.

The one sonic flaw comes in that first funky track (in other words, the best part of the album). When Mitchell and Jarman start blowing their saxes in rough unison, they sound not just rough (that’s intentional) but distorted and compressed. I have a theory on how this happened. When the ensemble wants to, they can play really loud—I mean really, really LOUD. My wife and I once saw them in the mid-‘80s at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater, a small venue designed for chamber music. At one point, they played as loud as I’d ever heard any five musicians play. My wife was pregnant with twins, who started moving inside her, for the first time, and not in a pleasant way. (We had to leave.) I suspect that, on this part of “Theme de Yoyo,” they started playing really, really loud, overloading the settings, and the engineer, caught by surprise, throttled the compression. At least, maybe in the mastering, he squeezed the horns into the left channel; the rest of the players aren’t much affected. On all the other tracks, though, they’re spread out across the soundstage, and everything sounds fine.

In any case, this is an enchanting album, the likes of which they don’t make much anymore. Get onboard the time machine.

.png)